Introduction

As a child, you learned to read and write. Regardless of how challenging or easy it was for you, compared to other things children learn, this is one of the most difficult ones kids have to do. It’s especially hard in English where there are so many different and unusual ways of writing what we say. For instance, the spelling “ough” can be used to represent so many different sounds. Rough (which rhymes with cuff), though (rhymes with go), slough (rhymes with do or cuff), bough (rhymes with cow), cough (rhymes with off), to name a few. Though phonics—a method of learning how to connect spelling patterns with sounds — can help to connect what we say with what we write, in many cases we must learn to memorize word shapes. How often have you said, “that word just doesn’t look right,” when spelling a word?

Compared to some languages, such as Romanian or Korean, where there is only one way to spell a word, based entirely on how it sounds, English is tricky. Our English spelling conventions were set when the language sounded differently from how it does today. English spelling evolved out of Greek, Latin and French spelling traditions, and early writers shoehorned the sounds of English into the Latin alphabet. As English pronunciation changed and became more diverse, spelling remained relatively constant. Today, people who are passionate about spelling reform run into many roadblocks because no one form of English pronunciation dominates the landscape—if spelling was made to match American pronunciation preferences, British English speakers wouldn’t use it. Not to mention the English of Canada, Australia, South Africa and the hundreds of different Englishes that now exist around the world.

As a result, actors can’t trust spelling as a way of capturing the pronunciation of a word. There are just too many variables for it to be a trusted system that you can rely on when you need it. What is the best way for an actor to write down a pronunciation, in a manner so that they will always know how that word should sound, even if it contains foreign sounds we don’t use in English?

The International Phonetic Alphabet (ipa) can be very helpful in this regard. Phonetics is the branch of linguistic science that studies the sounds of human speech, and the scientists who study it, called phoneticians, have, over the past 100 years, developed a system for accurately representing each sound that humans use in speech. In many ways, this system is very different from spelling, though phonetic transcription and spelling both use letter symbols to represent the words you hear or speak. To write something phonetically, you must listen very carefully to the way a person speaks and then try to accurately describe that utterance. The same word, spoken by two different people, could sound quite different, and so transcriptions of that word would reflect those differences. Many of your learned instincts about spelling words won’t help you when learning phonetics, and in some cases may actively work against you. In order to transcribe speech in ipa, you will have to learn to think differently about words and attend carefully to how you say and hear them.

In studying accents and dialects for performance, the first thing we need to isolate is the sounds of language, and ipa can help us to identify those individual building blocks. Unlike the alphabet that we use to spell our language, the ipa attempts to represent each sound with a single symbol. Each of those sounds is either a vowel, which can be an unrestricted voiced sound, like aaaah, or a consonant, which can be an unvoiced sound (i.e. just air), or a voiced one with the vocal folds vibrating, made in a range of places in the mouth and ways of shaping the air or voice, like ssssss or mmmmmm. While North American English variants are likely to use only about 17 of the ipa’s 25 pure vowel sounds, they also use around ten diphthongs, which are vowels that slide from one sound to another. For instance, the sound represented by the letter <y> in the word “my” slides from one sound to another in most English variants in North America, though for many people in the Southern US, it does not. Each accent or dialect uses its own variation of these core speech sounds that make up our spoken language, and so, as actors interested in portraying a variety of characters who will speak differently from us, we need to know more sounds than what we use personally. The ipa lists eighty-two possible consonant sounds, though mainstream English only uses about twenty-three of them. However, those speaking with accents and dialects of English frequently use more consonants than this minimum. You might not need to memorize all eighty-two consonants, but you’ll want to know how to recognize them, sound them and write them when the need arises.

With that much detail involved, many people become overwhelmed and struggle to learn the ipa. This workbook is designed to help you master the sounds, shapes and symbols quickly and get them anchored in your long-term memory, linking the shape of the symbol to its name and sound. More than anything, our goal is familiarity with the sounds, and the ipa symbols help us to keep track of them.

The International Phonetic Association devised these symbols using a number of criteria, familiarity being one of them. You will notice, if you look at the symbols below, that you will recognize many of the shapes—even the unusual ones are often merely letter symbols that have been turned, reversed, barred or added onto in some way. Some are symbols that have been “Romanized” to match the style of the other symbols borrowed from our standard alphabet but come from the Greek alphabet (e.g. [β]). A small number of symbol shapes, like the symbol for a kiss-like sound, [ʘ], were simply made up.

Before we begin, it is important to remember that the ipa follows some simple rules; though all languages are very complicated, the ipa is quite simple. One of the most important rules to remember is one symbol/one sound. The idea is that each distinct speech sound that you encounter should have its own identifiable symbol. This works quite well when one sticks to a single accent or dialect. But as you begin to learn and use more accents, dialects or languages, you start to realize that there are seemingly infinite ways of making speech sounds. To help users of the ipa distinguish between these subtleties, the ipa uses diacritical marks, sometimes called just diacritics. These small symbols are added onto the symbol shape, like an accented letter in French, to denote a modification to the base sound. For instance, one can make the consonant sound at the beginning of the word “tea” in a different way than most North Americans speak it, by hitting your tongue on the back of your teeth, making a “dental” sound. Try it yourself. (If this is the way you normally say the /t/ at the beginning of “tea,” try saying it with the front edge of your tongue on the flat part behind your upper front teeth but not touching them.) The ipa represents that kind of “T” with a slight modification to the symbol we usually use by adding a diacritic mark, in this case, below the symbol, rather than a whole new symbol (i.e. [t̪]).

There are many branches of linguistics that use the ipa on a daily basis. The ipa is, of course, informed by the field of phonetics, but also by phonology. While phonetics is the study and classification of speech sounds, phonology is the study of the system of sounds in a particular accent, dialect or language. For most of the twentieth century, theatre voice practitioners focused on phonetics, using the ipa to help actors, directors and coaches to describe the sounds of speech of a particular accent. Most voice practitioners had never heard of phonology, but relied on their innate knowledge of the rules of a standardized high-status form of English to make choices for the accents they were working on. Unfortunately, different accents, dialects and languages have different phonological rules, and so it’s easy to make errors on a deep level if you don’t understand the phonology of the lanɡuaɡe as spoken by the character you’re playing.

As you read this text, you will encounter many words transcribed in ipa, which will be set off from the text in square brackets. This denotes a transcription that represents the way something sounds, so we call it a phonetic transcription. For example, Ted is transcribed [tɛd]. Note that a proper noun is not capitalized in ipa, and sentences are not transcribed with a capital letter at the beginning. We are making a notation of a word’s sound, and we don’t say a word differently when it is a name or it begins a sentence.

At other times, the text will set off transcriptions between forward slashes, especially when discussing sounds as a group. For instance, there are many ways of making a sound we identify with the spelling <t>; to discuss that group as a whole the text would represent it as /t/. When a word is described in a broad, general way, we make a phonemic transcription, to show the underlying building blocks, or phonemes of the speech sounds involved, regardless of how the word might be pronounced in different accents. These kinds of transcriptions are found in dictionaries, like the Longman Pronouncing Dictionary by J.C. Wells, or in the Oxford English Dictionary. If we want a more detailed, specific transcription of a word as uttered in a specific accent, we would transcribe the word phonetically, trying to capture as much detail as possible about what specific sounds, or phones, actually come out a speaker’s mouth. This kind of phonetic transcription is used a lot in the study of accents and dialects for the actor. For example, a phonemic transcription of the word “red” is /red/, while a phonetic transcription might be [ɹ̹ɛd̚]. Notice how, in this case, the symbols for the phonemic transcription happen to be the same as those used in spelling, whereas the symbols for the phonetic one are quite different.

Decoding This Text

Sample words, spelled in English, will either appear in the text in italics, “in quotation marks,” or in ‹angle brackets›. You should also recognize that some capitalized versions of letters are used to represent completely different sounds, for example [ʏ, ɪ, ɢ, ɴ, ʀ] rather than [y, i, ɡ, n, r][1]. If you frequently use capital letters as part of your personal handwriting style, you’ll have to get out of that habit for transcribing in ipa.

The ipa symbols that you will see in this text are set in an ipa typeface typical of the kinds used on computers today. However at least some of the time you will need to write in the ipa, and not type it, and so we have to make some decisions about what is important in drawing the symbols. The International Phonetic Association (also known as the ipa) recommends that we draw or “print” the symbols in block form to match the shapes of the printed letterforms as best we can. In some cases, this is very easy as the letterforms, or glyphs, are exactly as we learned them as a child; in other cases, we have to learn new shapes or unlearn idiosyncratic habits (like crossing a /z/, for instance, ƶ —don’t do it!).

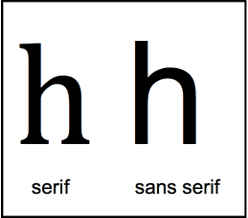

One of the issues that we confront in drawing the symbols is what to do with the serifs, the small ornamental “flares” at the ends of letter strokes. You may recognize that term from its opposite, “sans serif”, meaning a font without serifs. The simple, clean look of a sans serif font, such as Arial or Helvetica is familiar to all of us who use computers, smart phones or tablets. The sharp and crisp look of a serif typeface, with its little hooks and add-ons, such as Times New Roman or Georgia is hard to represent in handwriting. (Note that a font is a computer file that allows you to set your words in a typeface such as Fira Sans, the face used in this text, which is the design of the letterforms or glyphs.) We generally leave off the serifs, unless they give us something to help differentiate one symbol from another. In those instances, I will point out when a serif is important.

One of the issues that we confront in drawing the symbols is what to do with the serifs, the small ornamental “flares” at the ends of letter strokes. You may recognize that term from its opposite, “sans serif”, meaning a font without serifs. The simple, clean look of a sans serif font, such as Arial or Helvetica is familiar to all of us who use computers, smart phones or tablets. The sharp and crisp look of a serif typeface, with its little hooks and add-ons, such as Times New Roman or Georgia is hard to represent in handwriting. (Note that a font is a computer file that allows you to set your words in a typeface such as Fira Sans, the face used in this text, which is the design of the letterforms or glyphs.) We generally leave off the serifs, unless they give us something to help differentiate one symbol from another. In those instances, I will point out when a serif is important.

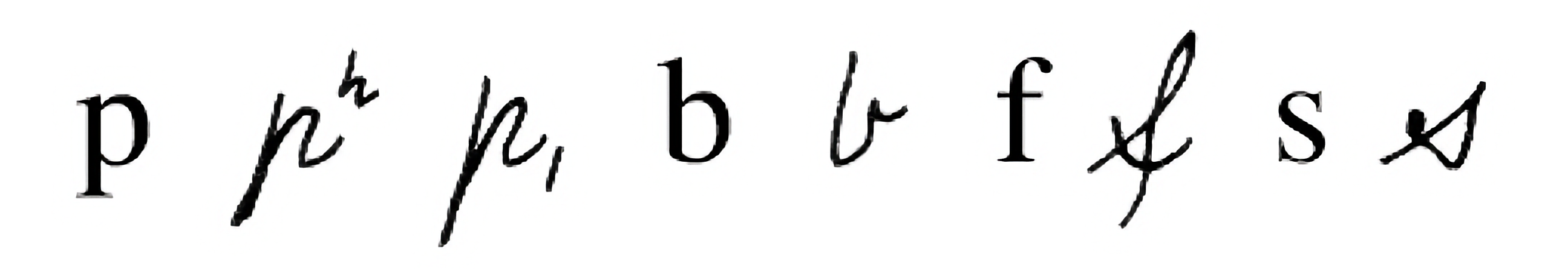

Some readers may be familiar with an older form of writing the ipa that was used in the theatre for many years. In Fig. 1 below, we see some letter-shapes as used in the classic speech text Speak with Distinction by Edith Skinner, which at one time was the dominant way for actors to learn the ipa in North America. Those letter-shapes are cursive in form, and do not attempt to replicate the shape of type. Back when phoneticians didn’t have recording devices, they wrote out what people said longhand, in the hope of capturing as much detail as possible as quickly as possible, using a joined, cursive form. We will not be using this style of ipa, though it is important to realize that over the years, many different ways of writing the ipa have evolved. This text is an attempt to bring theatre voice users into the world of linguists, phoneticians and dialecticians who have moved on since this cursive form was popular.

Practice Tips:

Take the time to draw the symbol carefully, as you did when you first learned to print. It has been suggested that you try to draw the symbols with your non-dominant hand, i.e. with your left hand if you are right-handed, and vice versa, if you are not. This will force you to take great care in shaping the symbols, slowing you down so that you have time to absorb the shape and connect it to sounds and images. Some people may find this too time consuming, or they might feel that their handwriting is bad enough already! Reminiscent of Betty Edward’s Drawing on the Right Side of the Brain approach, this technique helps to change how you perceive the symbol shape in the first place. Since many of the shapes look a lot like letter symbols you already know (with different names no less) it is very important that you find ways to challenge any preconceived notions you might have about a given shape/symbol. It is important to learn how to draw the symbols accurately, as some symbols look quite similar.

One technique is to use images to visualize the shapes of the letters, so that you see pictures in the symbols. This technique is derived from methods sometimes used to teach Japanese Kanji characters to foreigners. Many of the images are idiosyncratic; if you can think of your own image for the shape of the symbol, use it! Anything you can do to make this process more personal will help.

Conventions used in the imagery:

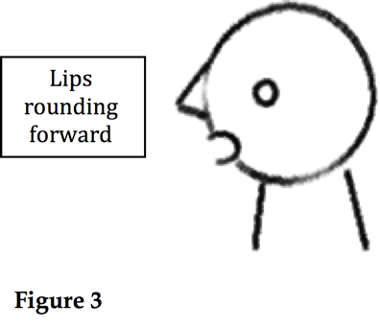

As in most anatomical drawings, there are some assumptions in phonetic symbols as to direction. The top of the page is the direction “up” (i.e. toward the top of your head, or toward the hard palate if we are talking about the action of your tongue). The bottom of the page is the direction “down” (toward your throat, or into the floor of the mouth when describing the tongue). The direction “front” is represented to the left, while “back” is always represented to the right. The easiest way for me to remember this is by imagining a face, which is always turned to the left side of the page. You’ll notice that in Fig. 2, the nose looks like an “L”, for left. This should help you to remember which way is forward.

The lips are an important part of shaping vowels and consonants. Lip rounding is represented in phonetics in a manner similar to the “directions”.

In Fig. 3, the mouth shape is rounded forward, to the left. It looks somewhat like the letter U (which makes your lips round when you say it) tipped to the left, or forward. This shape will be used throughout to represent the lips (e.g. the lip rounding diacritic mark—the mark below the symbol—is [ə̹].)

One issue that always seems to pester students is what to call the sounds and symbols. Each sound is, in a way, a name — make the sound, and we should know which symbol you are referring to. Begin with the sound. However, as we learn the sounds you will come to recognize that many sounds (at least at first) are very similar, and so merely saying the sound is not enough. In those instances, the name of the symbol that represents the sound may be useful. In time, you will learn to “tell your ash [æ] from your esh [ʃ].” And of course, there’s always a more complicated way to name the sounds! Linguists love to be descriptive in their naming conventions, so we might describe an /f/ sound as a “voiceless labiodental fricative”, and the vowel /o/ as a “close-mid back rounded vowel.”

- Notice that these symbols are all “small caps” which means that they are only as tall as a typical lower case letter. Apart from ascenders or descenders, as in [h, f, t, p, ɡ, q, ʃ], ipa symbols are all lowercase height. ↵