7 Talking and Listening

Jason S. Wrench; Narissra M. Punyanunt-Carter; and Katherine S. Thweatt

We are constantly interacting with people. We interact with our family and friends. We interact with our teachers and peers at school. We interact with customer service representatives, office coworkers, physicians/therapists, and so many other different people in average day. Humans are inherently social beings, so talking and listening to each other is a huge part of what we all do day-to-day.

7.1 The Importance of Everyday Conversations

Learning Objectives

- Realize the importance of conversation.

- Recognize the motives and needs for interpersonal communication.

- Discern conversation habits.

Most of us spend a great deal of our day interacting with other people through what is known as a conversation. According to Judy Apps, the word “conversation” is comprised of the words con (with) and versare (turn): “conversation is turn and turnabout – you alternate.”1 As such, a conversation isn’t a monologue or singular speech act; it’s a dyadic process where two people engage with one another in interaction that has multiple turns. Philosophers have been writing about the notion of the term “conversation” and its importance in society since the written word began.2 For our purposes, we will leave the philosophizing to the philosophers and start with the underlying assumption that conversation is an important part of the interpersonal experience. Through conversations with others, we can build, maintain, and terminate relationships.

Coming up with an academic definition for the term “conversation” is not an easy task. Instead, Donald Allen and Rebecca Guy offer the following explanation: “Conversation is the primary basis of direct social relations between persons. As a process occurring in real-time, conversation constitutes a reciprocal and rhythmic interchange of verbal emissions. It is a sharing process which develops a common social experience.”3 From this explanation, a conversation is how people engage in social interaction in their day-to-day lives. From this perspective, a conversation is purely a verbal process. For our purposes, we prefer Susan Brennan’s definition: “Conversation is a joint activity in which two or more participants use linguistic forms and nonverbal signals to communicate interactively.”4 Brennan does differentiate conversations, which can involve two or more people, from dialogues, which only involve two people. For our purposes, this distinction isn’t critical. What is essential is that conversations are one of the most common forms of interpersonal communication.

There is growing concern that in today’s highly mediated world, the simple conversation is becoming a thing of the past. Sherry Turkle is one of the foremost researchers on how humans communicate using technology. She tells the story of an 18-year-old boy who uses texting for most of his fundamental interactions. The boy wistfully told Turkle, “Someday, someday, but certainly not now, I’d like to learn how to have a conversation.”5 When she asks Millennials across the nation what’s wrong with holding a simple conversation:

“I’ll tell you what’s wrong with having a conversation. It takes place in real-time and you can’t control what you’re going to say.” So that’s the bottom line. Texting, email, posting, all of these things let us present the self as we want to be. We get to edit, and that means we get to delete, and that means we get to retouch, the face, the voice, the flesh, the body–not too little, not too much, just right.6

Is this the world we now live in? Have people become so addicted to their technology that holding a simple conversation is becoming passé?

You should not take communication for granted. Reading this book, you will notice how much communication can be critical in our personal and professional lives. Communication is a vital component of our life. A few years ago, a prison decided to lessen the amount of communication inmates could have with each other. The prison administrators decided that they did not want inmates to share information. Yet, over time, the prisoners developed a way to communicate with each other using codes on walls and tapping out messages through pipes. Even when inmates were not allowed to talk to each other via face-to-face, they were still able to find other ways to communicate.7

Types of Conversations

David Angle argues that conversations can be categorized based on directionality (one-way or two-way) and tone/purpose (cooperative or competitive).8 One-way conversations are conversations where an individual is talking at the other person and not with the other person. Although these exchanges are technically conversations because of the inclusion of nonverbal feedback, one of the conversational partners tends to monopolize the bulk of the conversation while the other partner is more of a passive receiver. Two-way conversations, on the other hand, are conversations where there is mutual involvement and interaction. In two-way conversations, people are actively talking, providing nonverbal feedback, and listening.

In addition to one vs. two-way interactions, Angle also believes that conversations can be broken down on whether they are cooperative or competitive. Cooperative conversations are marked by a mutual interest in what all parties within the conversation have to contribute. Conversely, individuals in competitive conversations are more concerned with their points of view than others within the conversation. Angle further breaks down his typology of conversations into four distinct types of conversation (Figure 7.1).

Discourse

The first type of conversation is one-way cooperative, which Angle labeled discourse. The purpose of a discourse conversation is for the sender to transmit information to the receiver. For example, a professor delivering a lecture or a speaker giving a speech.

Dialogue

The second type is what most people consider to be a traditional conversation: the dialogue (two-way, cooperative). According to Angle, “The goal is for participants to exchange information and build relationships with one another.”9 When you go on a first date, the general purpose of most of our conversations in this context is dialogue. If conversations take on one of the other three types, you could find yourself not getting a second date.

Debate

The third type of conversation is the two-way, competitive conversation, which Angle labels “debate.” The debate conversation is less about information giving and more about persuading. From this perspective, debate conversations occur when the ultimate goal of the conversation is to win an argument or persuade someone to change their thoughts, values, beliefs, and behaviors. Imagine you’re sitting in a study group and you’re trying to advocate for a specific approach to your group’s project. In this case, your goal is to persuade the others within the conversation to your point-of-view.

Diatribe

Lastly, Angle discusses the diatribe (one-way, competitive). The goal of the diatribe conversation is “to express emotions, browbeat those that disagree with you, and/or inspires those that share the same perspective.”10 For example, imagine that your best friend has come over to your dorm room, apartment, or house to vent about the grade they received on a test.

Communication Needs

There are many reasons why we communicate with each other, but what are our basic communication needs? The first reason why we communicate is for physical needs. Research has shown that we need to communicate with others because it keeps us healthier. There has been a direct link to mental and physical health. For instance, it has been shown that people who have cancer, depression, and even the common cold, can alleviate their symptoms simply by communicating with others. People who communicate their problems, feelings, and thoughts with others are less likely to hold grudges, anger, hostility, which in turn causes less stress on their minds and their bodies.

Another reason why we communicate with others is that it shapes who we are or identity needs. Perhaps you never realized that you were funny until your friends told you that you were quite humorous. Sometimes, we become who we are based on what others say to us and about us. For instance, maybe your mother told you that you are a gifted writer. You believe that information because you were told that by someone you respected. Thus, communication can influence the way that we perceive ourselves.

The third reason we communicate is for social needs. We communicate with others to initiate, maintain, and terminate relationships with others. These relationships may be personal or professional. In either case, we have motives or objectives for communicating with other people. The concept of communication motives was created by Rebecca Rubin. She found that there are six main reasons why individuals communicate with each other: control, relaxation, escape, inclusion, affection, and pleasure.

Control motives are means to gain compliance. Relaxation motives are ways to rest or relax. Escape motives are reasons for diversion or avoidance of other activities. Inclusion motives are ways to express emotion and to feel a link to the other person. Affection motives are ways to express one’s love and caring for another person. Pleasure motives are ways to communicate for enjoyment and excitement.

To maintain our daily routine, we need to communicate with others. The last reason we communicate is for practical needs. To exchange information or solve problems, we need to talk to others. Communication can prevent disasters from occurring. To create and/or sustain a daily balance in our lives, we need to communicate with other people. Hence, there is no escaping communication. We do it all the time.

Key Takeaways

- Communication is very important, and we should not take it for granted.

- There are six communication motives: control, affection, relaxation, pleasure, inclusion, and escape. There are four communication needs: physical, identity, social, and practical.

- Communication habits are hard to change.

Exercises

- Imagine if you were unable to talk to others verbally in a face-to-face situation. How would you adapt your communication so that you could still communicate with others? Why would you pick this method?

- Create a list of all the reasons you communicate and categorize your list based on communication motives and needs. Why do you think you communicate in the way that you do?

- Reflect on how you introduce yourself in a new situation. Write down what you typically say to a stranger. You can role play with a friend and then switch roles. What did you notice? How many of those statements are habitual? Why?

7.2 Sharing Personal Information

Learning Objectives

- Describe motives for self-disclosure.

- Appreciate the process of self-disclosure.

- Explain the consequences of self-disclosure.

- Draw and explain the Johari Window.

One of the primary functions of conversations is sharing information about ourselves. In Chapter 2, we discussed Berger and Calabrese’s Uncertainty Reduction Theory (URT).11 One of the basic axioms of URT is that, as verbal communication increases between people when they first meet, the level of uncertainty decreases. Specifically, the type of verbal communication generally discussed in initial interactions is called self-disclosure.12 Self-disclosure is the process of purposefully communicating information about one’s self. Sidney Jourard sums up self-disclosure as permitting one’s “true self” to be known to others.13

As we introduce the concept of self-disclosure in this section, it’s important to realize that there is no right or wrong way to self-disclose. Different people self-disclose for a wide range of different reasons and purposes. Emmi Ignatius and Marja Kokkonen found that self-disclosure can vary for several reasons:14

- Personality traits (shy people self-disclose less than extraverted people)

- Cultural background (Western cultures disclose more than Eastern cultures)

- Emotional state (happy people self-disclose more than sad or depressed people)

- Biological sex (females self-disclose more than males)

- Psychological gender (androgynous people were more emotionally aware, topically involved, and invested in their interactions; feminine individuals disclosed more in social situations, and masculine individuals generally did not demonstrate meaningful self-disclosure across contexts)

- Status differential (lower status individuals are more likely to self-disclose personal information than higher-status individuals)

- Physical environment (soft, warm rooms encourage self-disclosure while hard, cold rooms discourage self-disclosure)

- Physical contact (touch can increase self-disclosure, unless the other person feels that their personal space is being invaded, which can decrease self-disclosure)

- Communication channel (people often feel more comfortable self-disclosing when they’re not face-to-face; e.g., on the telephone or through computer-mediated communication)

As you can see, there are quite a few things that can impact how self-disclosure happens when people are interacting during interpersonal encounters.

Motives for Self-Disclosure

So, what ultimately motivates someone to self-disclose? Emmi Ignatius and Marja Kokkonen found two basic reasons for self-disclosure: social integration and impression management.15

Social Integration

The first reason people self-disclose information about themselves is simply to develop interpersonal relationships. Part of forming an interpersonal relationship is seeking to demonstrate that we have commonality with another person. For example, let’s say that it’s the beginning of a new semester, and you’re sitting next to someone you’ve never met before. You quickly strike up a conversation while you’re waiting for the professor to show up. During those first few moments of talking, you’re going to try to establish some kind of commonality. Maybe you’ll learn that you’re both communication majors or that you have the same favorite sports team or band. Self-disclosure helps us find these areas where we have similar interests, beliefs, values, attitudes, etc.… As humans, we have an innate desire to be social and meet people. And research has shown us that self-disclosure is positively related to liking.16 The more we self-disclose to others, the more they like us and vice versa.

However, we should mention that appropriate versus inappropriate self-disclosures depends on the nature of your relationship. When we first meet someone, we do not expect that person to start self-disclosing their deepest darkest secrets. When this happens, then we experience an expectancy violation. Judee Burgoon conceptualized expectancy violation theory as an understanding of what happens when an individual within an interpersonal interaction violates the norms for that interaction.17,18 Burgoon’s original expectancy violation theory (EVT) primarily analyzed what happened when individuals communicated nonverbally in a manner that was unexpected (e.g., standing too close while talking). Over the years, EVT has been expanded by many scholars to look at a range of different situations when communication expectations are violated.19 As a whole, EVT predicts that when individuals violate the norms of communication during an interaction, they will evaluate that interaction negatively. However, this does depend on the nature of the initial relationship. If we’ve been in a relationship with someone for a long time or if it’s someone we want to be in a relationship with, we’re more likely to overlook expectancy violations.

So, how does this relate to self-disclosure? Mostly, there are ways that we self-disclose that are considered “normal” during different types of interactions and contexts. What you disclose to your best friend will be different than what you disclose to a stranger at the bus station. What you disclose to your therapist will be different than what you disclose to your professor. When you meet a stranger, the types of self-disclosure tend to be reasonably common topics: your major, sports teams, bands, the weather, etc. If, however, you decide to self-disclose information that is overly personal, this would be perceived as a violation of the types of topics that are normally disclosed during initial interactions. As such, the other person is probably going to try to get out of that conversation pretty quickly. When people disclose information that is inappropriate to the context, those interactions will generally be viewed more negatively.20

From a psychological standpoint, finding these commonalities with others helps reinforce our self-concept. We find that others share the same interests, beliefs, values, attitudes, etc., which demonstrates that how we think, feel, and behave are similar to those around us. Admittedly, it’s not like we do all of this consciously.21

Impression Management

The second reason we tend to self-disclose is to portray a specific impression of who we are as individuals to others. Impression management is defined as “the attempt to generate as favorable an impression of ourselves as possible, particularly through both verbal and nonverbal techniques of self-presentation.”22 Basically, we want people to view us in a specific way, so we communicate with others in an attempt to get others to see us that way. Research has found we commonly use six impression management techniques during interpersonal interactions: self-descriptions, accounts, apologies, entitlements and enhancements, flattery, and favors.23,24,25

Self-Descriptions

The first type of impression management technique we can use is self-descriptions, or talking about specific characteristics of ourselves. For example, if you want others to view you professionally, you would talk about the work that you’ve accomplished. If you want others to see you as someone fun to be around, you will talk about the parties you’ve thrown. In both of these cases, the goal is to describe ourselves in a manner that we want others to see.

Accounts

The second type of impression management is accounts. Accounts “are explanations of a predicament-creating event designed to minimize the apparent severity of the predicament.”26 According to William Gardner and Mark Martinko, in accounts, “actors may deny events occurred, deny causing events, offer excuses, or justify incidents.”27 Basically, accounts occur when an individual is attempting to explain something that their interactant may already know.

For the purposes of initial interactions, imagine that you’re on a first date and your date has heard that you’re a bit of a “player.” An account may be given to downplay your previous relationships or explain away the rumors about your previous dating history.

Apologies

The third type of impression management tactics is apologies. According to Barry Schlenker, apologies are “are designed to convince the audience that the undesirable event should not be considered a fair representation of what the actor is ‘really like.’”28 An apology occurs when someone admits that they have done something wrong while attempting to downplay the severity of the incident or the outcomes.

Imagine you just found out that a friend of yours told a personal story about you during class as an example. Your friend could offer an apology, admitting that they shouldn’t have told the story, but also emphasize that it’s not like anyone in the class knows who you are. In essence, the friend admits that they are wrong, but also downplays the possible outcomes from the inappropriate disclosure of your story.

Entitlements and Enhancements

The fourth type of impression management tactic is the use of entitlements and enhancements. Entitlements and enhancements are “designed to explain a desirable event in a way that maximizes the desirable implications for the actor.”29 Primarily, “entitlements are designed to maximize an actor’s apparent responsibility for an event; enhancements are designed to maximize the favorability of an event itself.”30 In this case, the goal is to make one’s self look even better than maybe they actually are.

For our examples, let’s look at entitlements and enhancements separately. For an example of an entitlement, imagine that you’re talking to a new peer in class and they tell you about how they single-handedly organized a wildly popular concert that happened over the weekend. In this case, the individual is trying to maximize their responsibility for the party in an effort to look good.

For an example of an enhancement, imagine that in the same scenario, the individual talks less about how they did the event single-handedly and talks more about how amazing the event itself was. In this case, they’re aligning themselves with the event, so the more amazing the event looks, the better you’ll perceive them as an individual.

Flattery

The fifth impression management tactic is the use of flattery, or the use of compliments to get the other person to like you more. In this case, there is a belief that if you flatter someone, they will see you in a better light. Imagine there’s a new player on your basketball team. Almost immediately, they start complimenting you on your form and how they wish they could be as good as you are. In this case, the person may be completely honest, but the use of flattery will probably get you to see that person more positively as well.

Favors

The last tactic that researches have described for impression management is favors. Favors “involve doing something nice for someone to gain that person’s approval.”31 One way that we get others to like us is to do things for them. If we want our peers in class to like us, then maybe we’ll share our notes with them when they’re absent. We could also volunteer to let someone use our washer and dryer if they don’t have one. There are all kinds of favors that we can do for others. Although most of us don’t think of favors as tactics for managing how people perceive us, they have an end result that does.

Social Penetration Theory

In 1973, Irwin Altman and Dalmas Taylor were interested in discovering how individuals become closer to each other.32 They believed that the method of self-disclosure was similar to social penetration and hence created the social penetration theory. This theory helps to explain how individuals gradually become more intimate based on their communication behaviors. According to the social penetration theory, relationships begin when individuals share non-intimate layers and move to more intimate layers of personal information.33

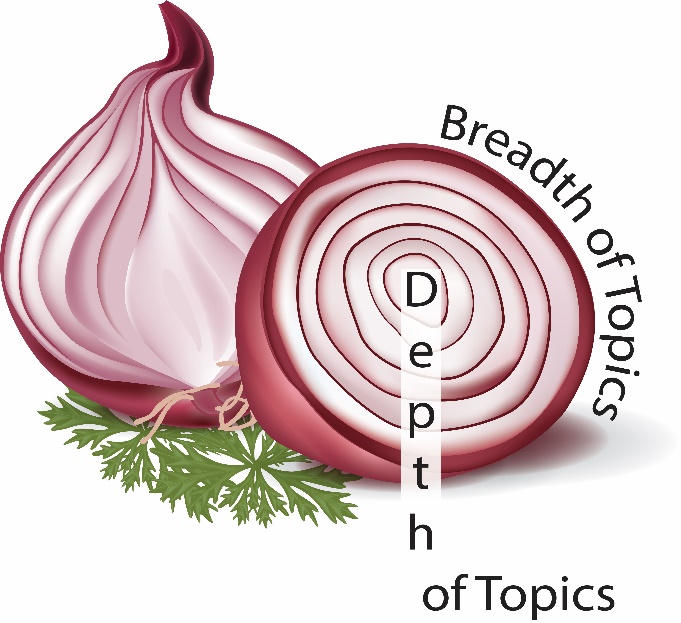

Altman and Taylor believed that individuals discover more about others through self-disclosure. How people comprehend others on a deeper level helps us also gain a better understanding of ourselves. The researchers believe that penetration happens gradually. The scholars describe their theory visually like an onion with many rings or levels.34 A person’s personality is like an onion because it has many layers (Figure 7.2). We have an outer layer that everyone can see (e.g., hair color or height), and we have very personal layers that people cannot see (e.g., our dreams and career aspirations). Three factors affect what people chose to disclose. The first is personal characteristics (e.g., introverted or extraverted). The second is the possibility of any reward or cost with disclosing to the other person (e.g., information might have repercussions if the receiver does not like or agree with you). And the third is the situational context (e.g., telling your romantic partner that you want to terminate the relationship on your wedding day).

When people first meet each other, they start from their outer rings and slowly move towards the core. The researchers described how people typically would go through various stages to become closer. The first stage is called the orientation stage, where people communicate on very superficial matters like the weather. The next stage is the exploratory affective stage, where people will disclose more about their feelings about normal topics like favorite foods or movies. Many of our friendships remain at this stage. The third stage is more personal and called the affective stage, where people engage in more private topics. The fourth stage is the stable stage, where people will share their most intimate details. The last stage is not obligatory and does not necessarily happen in every relationship, it is the depenetration stage, where people start to decrease their disclosures.

Social penetration theory also contains two different aspects. The first aspect is breadth, which refers to what topics individuals are willing to talk about with others. For instance, some people do not like to talk about religion and politics because it is considered inappropriate. The second aspect is depth, which refers to how deep a person is willing to go in discussing certain topics. For example, some people don’t mind sharing information about themselves in regards to their favorite things. Still, they may not be willing to share their most private thoughts about themselves because it is too personal. The researchers believe that by self-disclosing to others both in breadth and depth, then it could lead to more relational closeness.

Johari Window

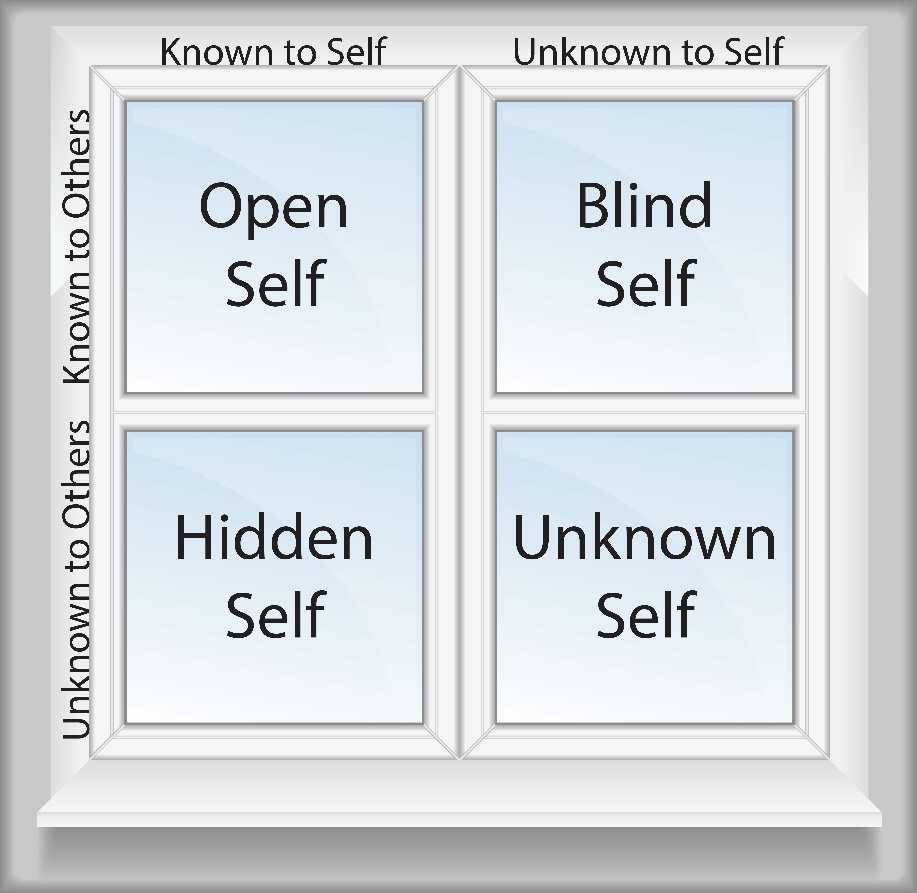

The name “Johari” is a combination of the two researchers who originated the concept: Joseph Luft (Jo) and Harrington Ingham (hari).35 The basic idea behind the Johari Window is that we build trust in our interpersonal relationships as we self-disclose revealing information about ourselves, and we learn more about ourselves as we receive feedback from the people with whom we are interacting. As you can see in Figure 7.3, the Johari Window is represented by four window panes. Two window panes refer to ourselves, and two refer to others. First, when discussing ourselves, we have to be aware that somethings about ourselves are known to us, and others are not. For example, we may be completely aware of the fact that we are extraverted and love talking to people (known to self). However, we may not be aware of how others tend to view our extraversion as positive or negative (unknown to self). The second part of the window is what is known to others and unknown to others. For example, some common information known to others includes your height, weight, hair color, etc. At the same time, there is a bunch of information that people don’t know about us: deepest desires, joys, goals in life, etc. Ultimately, the Johari Window breaks this into four different quadrants (Figure 7.3).

Open Self

The first quadrant of the Johari Window is the open self, or when information is known to both ourselves and others. Although some facets are automatically known, others become known as we disclose more and more information about ourselves with others. As we get to know people and self-disclose and increasingly deeper levels, the open self quadrant grows. For the purposes of thinking about discussions and self-disclosures, the open self is where the bulk of this work ultimately occurs.

Information in the open self can include your attitudes, beliefs, behaviors, emotions/feelings, experiences, and values that are known to both the person and to others. For example, if you wear a religious symbol around your neck (Christian Cross, Jewish Start of David, Islamic Crescent Moon and Star, etc.), people will be able to ascertain certain facts about your religious beliefs immediately.

Hidden Self

The second quadrant is what is known to ourselves but is not known to others. All of us have personal information we may not feel compelled to reveal to others. For example, if you’re a member of the LGBTQIA+ community, you may not feel the need to come out during your first encounter with someone new. It’s also possible that you’ll keep this information from your friends and family for a long time.

Think about your own life, what types of things do you keep hidden from others? One of the reasons we keep things hidden is because it’s hard to open ourselves up to being vulnerable. Typically, the hidden self will decrease as a relationship grows. However, if someone ever violates our trust and discusses our hidden self with others, we are less likely to keep disclosing this information in the future. If the trust violation is extreme enough, we may discontinue that relationship altogether.

Blind Self

The third quadrant is called the blind self because it’s what we don’t know about ourselves that is known by others. For example, during an initial interaction, we may not know how the other person is reacting to us. We may think that we’re coming off as friendly, but the other person may be perceiving us as shy or even pushy. One way to decrease the blind self is by soliciting feedback from others. As others reveal more of our blind selves, we can become more self-aware of how others perceive us.

One problem with the blind self is that how people view us and how we view ourselves can often be radically different. For example, people may perceive you as cocky, but in reality, you’re scared to death. It’s important to decrease the blind self during our interactions with others, because how people view us will determine how they interact with us.

Unknown Self

Lastly, we have the unknown self, or when information is not known by ourselves or others. The unknown self can include aptitudes/talents, attitudes/feelings, behaviors, capabilities, etc. that are unknown to us or others. For example, you may have a natural talent to play the piano. Still, if you’ve never sat down in front of a piano, neither you nor others would have any way of knowing that you have the aptitude/talent for playing the piano. Sometimes parts of the unknown self are just under the surface and will arise with time and in the right contexts, but other times no one will ever know these unknown parts.

One other area that can affect the unknown self involves prior experiences. It’s possible that you experienced a traumatic event that closes you down in a specific area. For example, imagine that you are an amazing writer, but someone, when you were in the fourth grade, made fun of a story you wrote, so you never tried writing again. In this case, the aptitude/talent for writing has been stamped out because of that one traumatic experience as a child. Sadly, a lot of us probably have a range of aptitudes/talents, attitudes/feelings, behaviors, capabilities, etc. that were stopped because of traumas throughout our lives.

Key Takeaways

- We self-disclose to share information with others. It allows us to express our thoughts, feelings, and behaviors.

- Self-disclosure includes levels of disclosure, reciprocity in disclosure, and appropriate disclosure.

- There can be positive and negative consequences of self-disclosure. These consequences can strengthen how you feel or create distance between you and someone else.

- The Johari Window is a model that helps to illustrate self-disclosure and the process by which you interact with other people.

Exercises

- Create a self-penetration diagram for yourself. What topics are you open to talk about? What are you not willing to discuss? Then compare with another student in class. How were you similar or dissimilar? Why do you think these differences/similarities exist?

- Think of a time when you’ve used the six different impression management techniques. How effective were you with each technique? What could you have done differently?

- Draw your own Johari Window. Fill in each of the window panes with a topic of self-disclosure. You will probably need to ask a close friend or family member to help you with the unknown self pane. Why did you put what you put? Does it make sense? Why?

7.3 Listening

Learning Objectives

- Differentiate between hearing and listening.

- Understand how to listen effectively.

- Recognize the different types of listening.

When it comes to daily communication, we spend about 45% of our listening, 30% speaking, 16% reading, and 9% writing.36 However, most people are not entirely sure what the word “listening” is or how to do it effectively.

Hearing Is Not Listening

Hearing refers to a passive activity where an individual perceives sound by detecting vibrations through an ear. Hearing is a physiological process that is continuously happening. We are bombarded by sounds all the time. Unless you are in a sound-proof room or are 100% deaf, we are constantly hearing sounds. Even in a sound-proof room, other sounds that are normally not heard like a beating heart or breathing will become more apparent as a result of the blocked background noise.

Listening, on the other hand, is generally seen as an active process. Listening is “focused, concentrated attention for the purpose of understanding the meanings expressed by a [source].”37 From this perspective, hearing is more of an automatic response when your ear perceives information; whereas, listening is what happens when we purposefully attend to different messages.

We can even take this a step further and differentiate normal listening from critical listening. Critical listening is the “careful, systematic thinking and reasoning to see whether a message makes sense in light of factual evidence.”38 From this perspective, it’s one thing to attend to someone’s message, but something very different to analyze what the person is saying based on known facts and evidence.

Let’s apply these ideas to a typical interpersonal situation. Let’s say that you and your best friend are having dinner at a crowded restaurant. Your ear is going to be attending to a lot of different messages all the time in that environment, but most of those messages get filtered out as “background noise,” or information we don’t listen to at all. Maybe then your favorite song comes on the speaker system the restaurant is playing, and you and your best friend both attend to the song because you both like it. A minute earlier, another song could have been playing, but you tuned it out (hearing) instead of taking a moment to enjoy and attend to the song itself (listen). Next, let’s say you and your friend get into a discussion about the issues of campus parking. Your friend states, “There’s never any parking on campus. What gives?” Now, if you’re critically listening to what your friend says, you’ll question the basis of this argument. For example, the word “never” in this statement is problematic because it would mean that the campus has zero available parking, which is probably not the case. Now, it may be difficult for your friend to find a parking spot on campus, but that doesn’t mean that there’s “never any parking.” In this case, you’ve gone from just listening to critically evaluating the argument your friend is making.

Model of Listening

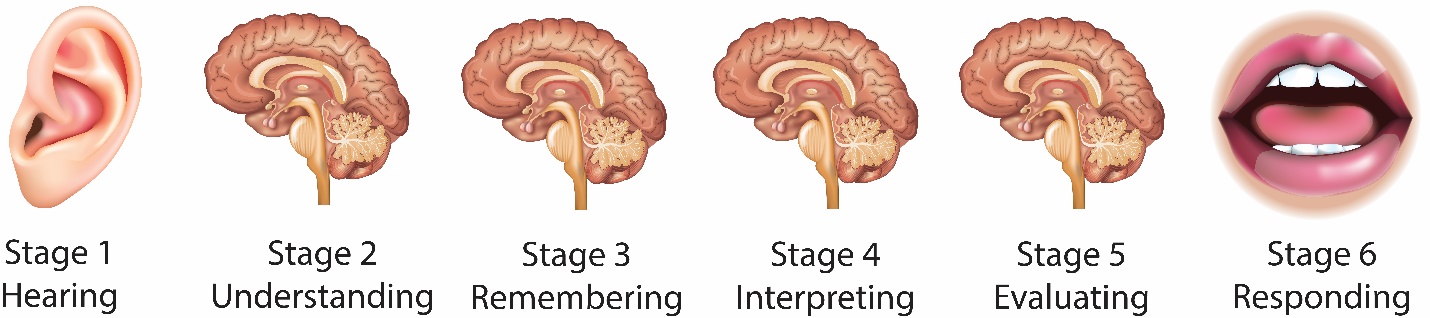

Judi Brownell created one of the most commonly used models for listening.39 Although not the only model of listening that exists, we like this model because it breaks the process of hearing down into clearly differentiated stages: hearing, understanding, remembering, interpreting, evaluating, and responding (Figure 7.4).

Hearing

From a fundamental perspective, for listening to occur, an individual must attend to some kind of communicated message. Now, one can argue that hearing should not be equated with listening (as we did above), but it is the first step in the model of listening. Simply, if we don’t attend to the message at all, then communication never occurred from the receiver’s perspective.

Imagine you’re standing in a crowded bar with your friends on a Friday night. You see your friend Darry and yell her name. In that instant, you, as a source of a message, have attempted to send a message. If Darry is too far away, or if the bar is too loud and she doesn’t hear you call her name, then Darry has not engaged in stage one of the listening model. You may have tried to initiate communication, but the receiver, Darry, did not know that you initiated communication.

Now, to engage in mindful listening, it’s important to take hearing seriously because of the issue of intention. If we go into an interaction with another person without really intending to listening to what they have to say, we may end up being a passive listener who does nothing more than hear and nod our heads. Remember, mindful communication starts with the premise that we must think about our intentions and be aware of them.

Understanding

The second stage of the listening model is understanding, or the ability to comprehend or decode the source’s message. When we discussed the basic models of human communication in Chapter 2, we discussed the idea of decoding a message. Simply, decoding is when we attempt to break down the message we’ve heard into comprehensible meanings. For example, imagine someone coming up to you asking if you know, “Tintinnabulation of vacillating pendulums in inverted, metallic resonant cups.” Even if you recognize all of the words, you may not completely comprehend what the person is even trying to say. In this case, you cannot decode the message. Just as an FYI, that means “jingle bells.”

Remembering

Once we’ve decoded a message, we have to actually remember the message itself, or the ability to recall a message that was sent. We are bombarded by messages throughout our day, so it’s completely possible to attend to a message and decode it and then forget it about two seconds later.

For example, I always warn my students that my brain is like a sieve. If you tell me something when I’m leaving the class, I could easily have forgotten what you told me three seconds later because my brain switches gear to what I’m doing next: I run into another student into in the hallway; another thought pops into my head; etc. As such, I always recommend emailing me important things, so I don’t forget them. In this case, it’s not that I don’t understand the message; I just get distracted, and my remembering process fails me. This problem plagues all of us.

Interpreting

The next stage in the HURIER Model of Listening is interpreting. “Interpreting messages involves attention to all of the various speaker and contextual variables that provide a background for accurately perceived messages.”40 So, what do we mean by contextual variables? A lot of the interpreting process is being aware of the nonverbal cues (both oral and physical) that accompany a message to accurately assign meaning to the message.

Imagine you’re having a conversation with one of your peers, and he says, “I love math.” Well, the text itself is demonstrating an overwhelming joy and calculating mathematical problems. However, if the message is accompanied by an eye roll or is said in a manner that makes it sound sarcastic, then the meaning of the oral phrase changes. Part of interpreting a message then is being sensitive to nonverbal cues.

Evaluating

The next stage is the evaluating stage, or judging the message itself. One of the biggest hurdles many people have with listening is the evaluative stage. Our personal biases, values, and beliefs can prevent us from effectively listening to someone else’s message.

Let’s imagine that you despise a specific politician. It’s gotten to the point where if you hear this politician’s voice, you immediately change the television channel. Even hearing other people talk about this politician causes you to tune out completely. In this case, your own bias against this politician prevents you from effectively listening to their message or even others’ messages involving this politician. Overcoming our own biases against the source of a message or the content of a message in an effort to truly listen to a message is not easy. One of the reasons listening is a difficult process is because of our inherent desire to evaluate people and ideas.

When it comes to evaluating another person’s message, it’s important to remember to be mindful. As we discussed in Chapter 1, to be a mindful communicator, you must listen with an open ear that is nonjudging. Too often, we start to evaluate others’ messages with an analytical or cold quality that is antithetical to being mindful.

Responding

In Figure 7.4, hearing is represented by an ear, the brain represents the next four stages, and a person’s mouth represents the final stage. It’s important to realize that effective listening starts with the ear and centers in the brain, and only then should someone provide feedback to the message itself. Often, people jump from hearing and understanding to responding, which can cause problems as they jump to conclusions that have arisen by truncated interpretation and evaluation.

Ultimately, how we respond to a source’s message will dictate how the rest of that interaction will progress. If we outright dismiss what someone is saying, we put up a roadblock that says, “I don’t want to hear anything else.” On the other hand, if we nod our heads and say, “tell me more,” then we are encouraging the speaker to continue the interaction. For effective communication to occur, it’s essential to consider how our responses will impact the other person and our relationship with that other person.

Overall, when it comes to being a mindful listener, it’s vital to remember COAL: curiosity, openness, acceptance, and love.41 We need to go into our interactions with others and try to see things from their points of view. When we engage in COAL, we can listen mindfully and be in the moment.

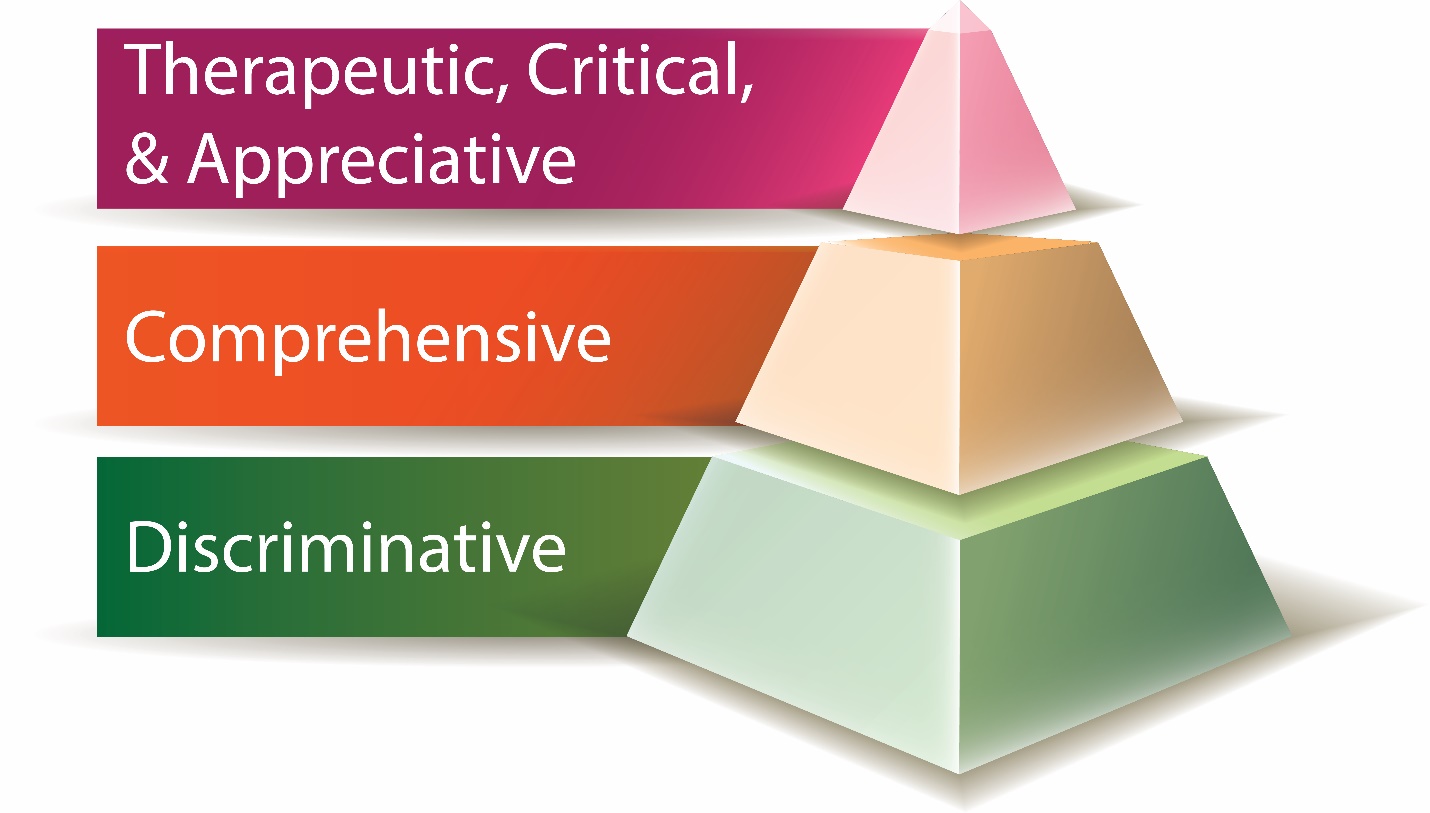

Taxonomy of Listening

Now that we’ve introduced the basic concepts of listening, let’s examine a simple taxonomy of listening that was created by Andrew Wolvin and Carolyn Coakley.42 The basic premise of the Wolvin and Coakley taxonomy of listening is that there are fundamental parts to listening and then higher-order aspects of listening (Figure 7.5). Let’s look at each of these parts separately.

Discriminative

The base level of listening is what Wolvin and Coakley called discriminative listening, or distinguishing between auditory and visual stimuli and determining which to actually pay attention to. In many ways, discriminative listening focuses on how hearing and seeing a wide range of different stimuli can be filtered and used.

We’re constantly bombarded by a variety of messages in our day-to-day lives. We have to discriminate between which messages we want to pay attention to and which ones we won’t. As a metaphor, think of discrimination as your email inbox. Every day you have to filter out messages (aka spam) to find the messages you want to actually read. In the same way, our brains are constantly bombarded by messages, and we have to filter some in and most of them out.

Comprehensive

If we achieve discriminative listening, then we can progress to comprehensive listening. “Comprehensive listening requires the listener to use the discriminative skills while functioning to understand and recall the speaker’s information.”43 If we go back and look at Figure 7.4, we can see that comprehensive listening essentially aligns with understanding and remembering.

Wolvin and Coakley argued that discriminative and comprehensive listening are foundational levels of listening. If these foundational levels of listening are met, then they can progress to the other three, higher-order levels of listening: therapeutic, critical, and appreciative.

Therapeutic

Therapeutic listening occurs when an individual is a sounding board for another person during an interaction. For example, your best friend just fought with their significant other and they’ve come to you to talk through the situation.

Critical

The next aspect of listening is critical listening, or really analyzing the message that is being sent. Instead of just being a passive receiver of information, the essential goal of listening is to determine the acceptability or validity of the message(s) someone is sending.

Appreciative

Lastly, we have appreciative listening, which is when someone simply enjoys the act of listening or the message being sent. For example, let’s say you’re watching a Broadway musical or play or even a new movie at the cinema. While you may be engaged critically, you also may be simply appreciative and enjoying the act of listening to the message.

Listening Styles

Now that we have a better understanding of how listening works, let’s talk about four different styles of listening researchers have identified. Kittie Watson, Larry Barker, and James Weaver defined listening styles as “attitudes, beliefs, and predispositions about the how, where, when, who, and what of the information reception and encoding process.”44 Watson et al. identified four distinct listening styles: people, content, action, and time. Before progressing to learning about the different listening styles, take a minute to complete the measure in Table 7.1, The Listening Style Questionnaire. The Listening Style Questionnaire is based on the original work of Watson, Barker, and Weaver.45

Instructions: Read the following questions and select the answer that corresponds with how you tend to listen to public speeches. Do not be concerned if some of the items appear similar. Please use the scale below to rate the degree to which each statement applies to you:

| Strongly Disagree | Disagree | Neutral | Agree | Strongly Agree |

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

_____1. I am very attuned to public speaker’s emotions while listening to them.

_____2. I keep my attention on a public speaker’s feelings why they speak.

_____3. I listen for areas of similarity and difference between me and a public speaker.

_____4. I generally don’t pay attention to a speaker’s emotions.

_____5. When listening to a speaker’s problems, I find myself very attentive.

_____6. I prefer to listen to people’s arguments while they are speaking.

_____7. I tend to tune out technical information when a speaker is speaking.

_____8. I wait until all of the arguments and evidence is presented before judging a speaker’s message.

_____9. I always fact check a speaker before forming an opinion about their message.

_____10. When it comes to public speaking, I want a speaker to keep their opinions to themself and just give me the facts.

_____11. A speaker needs to get to the point and tell me why I should care.

_____12. Unorganized speakers drive me crazy.

_____13. Speakers need to stand up, say what they need to say, and sit down.

_____14. If a speaker wants me to do something, they should just say it directly.

_____15. When a speaker starts to ramble on, I really start to get irritated.

_____16. I have a problem listening to someone give a speech when I have other things to do, places to be, or people to see.

_____17. When I don’t have time to listen to a speech, I have no problem telling someone.

_____18. When someone is giving a speech, I’m constantly looking at my watch or clocks in the room.

_____19. I avoid speeches when I don’t have the time to listen to them.

_____20. I have no problem listening to a speech even when I’m in a hurry.

Scoring:

People-Oriented Listener

A: Add scores for items 1, 2, 3, 5 and place total on line. _____

B: Place score for item 4 on the line._____

C: Take the total from A and add 6 to the score. Place the new number on the line._____

Final Score: Now subtract B from C. Place your final score on the line._____

Content-Oriented Listener

A: Add scores for items 6, 8, 9, 10 and place total on line._____

B: Place score for item 7 on the line._____

C: Take the total from A and add 6 to the score. Place the new number on the line._____

Final Score: Now subtract B from C. Place your final score on the line._____

Action-Oriented Listener

Final Score: Add items 11, 12, 13, 14, 15_____

Time-Oriented Listener

A: Add scores for items 16, 17, 19 and place total on line._____

B: Add scores for items 18 & 20 and place total on line._____

C: Take the total from A and add 12 to the score. Place the new number on the line._____

Final Score: Now subtract B from C. Place your final score on the line._____

Interpreting Your Score

For each of the four subscales, scores should be between 5 and 25. If your score is above 18, you are considered to have high levels of that specific listening style. If your score is below 12, you’re considered to have low levels of that specific listening style.

Based on:

Watson, K. W., Barker, L. L., & Weaver, J. B., III. (1992, March). Development and validation of the Listener Preference Profile. Paper presented at the International Listening Association in Seattle, WA.

Table 7.1 Listening Style Questionnaire

The Four Listening Styles

People

The first listening style is the people-oriented listening style. People-oriented listeners tend to be more focused on the person sending the message than the content of the message. As such, people-oriented listeners focus on the emotional states of senders of information. One way to think about people-oriented listeners is to see them as highly compassionate, empathic, and sensitive, which allows them to put themselves in the shoes of the person sending the message.

People-oriented listeners often work well in helping professions where listening to the person and understanding their feelings is very important (e.g., therapist, counselor, social worker, etc.). People-oriented listeners are also very focused on maintaining relationships, so they are good at casual conservation where they can focus on the person.

Action

The second listening style is the action-oriented listener. Action-oriented listeners are focused on what the source wants. The action-oriented listener wants a source to get to the point quickly. Instead of long, drawn-out lectures, the action-oriented speaker would prefer quick bullet points that get to what the source desires. Action-oriented listeners “tend to preference speakers that construct organized, direct, and logical presentations.”46

When dealing with an action-oriented listener, it’s important to realize that they want you to be logical and get to the point. One of the things action-oriented listeners commonly do is search for errors and inconsistencies in someone’s message, so it’s important to be organized and have your facts straight.

Content

The third type of listener is the content-oriented listener, or a listener who focuses on the content of the message and process that message in a systematic way. Of the four different listening styles, content-oriented listeners are more adept at listening to complex information. Content-oriented listeners “believe it is important to listen fully to a speaker’s message prior to forming an opinion about it (while action listeners tend to become frustrated if the speaker is ‘wasting time’).”47

When it comes to analyzing messages, content-oriented listeners really want to dig into the message itself. They want as much information as possible in order to make the best evaluation of the message. As such, “they want to look at the time, the place, the people, the who, the what, the where, the when, the how … all of that. They don’t want to leave anything out.”48

Time

The final listening style is the time-oriented listening style. Time-oriented listeners are sometimes referred to as “clock watchers” because they’re always in a hurry and want a source of a message to speed things up a bit. Time-oriented listeners “tend to verbalize the limited amount of time they are willing or able to devote to listening and are likely to interrupt others and openly signal disinterest.”49

They often feel that they are overwhelmed by so many different tasks that need to be completed (whether real or not), so they usually try to accomplish multiple tasks while they are listening to a source. Of course, multitasking often leads to someone’s attention being divided, and information being missed.

Thinking About the Four Listening Types

Kina Mallard broke down the four listening styles and examined some of the common positive characteristics, negative characteristics, and strategies for communicating with the different listening styles (Table 7.2).50

| People-Oriented Listeners | ||

|---|---|---|

| Positive Characteristics | Negative Characteristics | Strategies for Communicating with People-Oriented Listeners |

| Show care and concern for others | Over involved in feelings of others | Use stories and illustrations to make points |

| Are nonjudgmental | Avoid seeing faults in others | Use “we” rather than “I” in conversations |

| Provide clear verbal and nonverbal feedback signals | Internalize/adopt emotional states of others | Use emotional examples and appeals |

| Are interested in building relationships | Are overly expressive when giving feedback | Show some vulnerability when possible |

| Notice others’ moods quickly | Are nondiscriminating in building relationships | Use self-effacing humor or illustrations |

| Action-Oriented Listeners | ||

|---|---|---|

| Positive Characteristics | Negative Characteristics | Strategies for Communicating with Action-Oriented Listeners |

| Get to the point quickly | Tend to be impatient with rambling speakers | Keep main points to three or fewer |

| Give clear feedback concerning expectations | Jump ahead and reach conclusions quickly | Keep presentations short and concise |

| Concentrate on understanding task | Jump ahead or finishes thoughts of speakers | Have a step-by-step plan and label each step |

| Help others focus on what’s important | Minimize relationship issues and concerns | Watch for cues of disinterest and pick up vocal pace at those points or change subjects |

| Encourage others to be organized and concise | Ask blunt questions and appear overly critical | Speak at a rapid but controlled rate |

| Content-Oriented Listeners | ||

|---|---|---|

| Positive Characteristics | Negative Characteristics | Strategies for Communicating with Content-Oriented Listeners |

| Value technical information | Are overly detail oriented | Use two-side arguments when possible |

| Test for clarity and understanding | May intimidate others by asking pointed questions | Provide hard data when available |

| Encourage others to provide support for their ideas | Minimize the value of nontechnical information | Quote credible experts |

| Welcome complex and challenging information | Discount information from nonexperts | Suggest logical sequences and plan |

| Look at all sides of an issue | Take a long time to make decisions | Use charts and graphs |

| Original Source: Mallard, K. S. (1999). Lending an ear: The chair’s role as listener. The Department Chair, 9(3), 1-13. Used with Permission from the Author |

||

| Time-Oriented Listeners | ||

|---|---|---|

| Positive Characteristics | Negative Characteristics | Strategies for Communicating with Time-Oriented Listeners |

| Manage and save time | Tend to be impatient with time wasters | Ask how much time the person has to listen |

| Set time guidelines for meeting and conversations | Interrupt others | Try to go under time limits when possible |

| Let others know listening-time requirements | Let time affect their ability to concentrate | Be ready to cut out necessary examples and information |

| Discourage wordy speakers | Rush speakers by frequently looking at watches/clock | Be sensitive to nonverbal cues indicating impatience or a desire to leave |

| Give cues to others when time is being wasted | Limit creativity in others by imposing time pressures | Get to the bottom line quickly |

Table 7.2 Understanding the Four Listening Styles

Hopefully, this section has helped you further understand the complexity of listening. We should mention that many people are not just one listening style or another. It’s possible to be a combination of different listening styles. However, some of the listening style combinations are more common. For example, someone who is action-oriented and time-oriented will want the bare-bones information so they can make a decision. On the other hand, it’s hard to be a people-oriented listener and time-oriented listener because being empathic and attending to someone’s feelings takes time and effort.

Mindfulness Activity

One of the hardest skills to master when it comes to mindfulness is mindful listening. To engage in mindful listening, Elaine Smookler recommends using the HEAR method:

One of the hardest skills to master when it comes to mindfulness is mindful listening. To engage in mindful listening, Elaine Smookler recommends using the HEAR method:

- HALT — Halt whatever you are doing and offer your full attention.

- ENJOY — Enjoy a breath as you choose to receive whatever is being communicated to you—wanted or unwanted.

- ASK — Ask yourself if you really know what they mean, and if you don’t, ask for clarification. Instead of making assumptions, bring openness and curiosity to the interaction. You might be surprised at what you discover.

- REFLECT — Reflect back to them what you heard. This tells them that you were really listening.51

For this mindfulness activity, we want you to engage in mindful listening. Start by having a conversation with a friend, romantic partner, or family member. Before beginning the conversation, find a location that has minimal distractions, so try not to engage in this activity in a public space. Also, turn off the television and radio. The goal is to focus your attention on the other person. Start by employing the HEAR method for listening during your conversation. After you have finished this conversation, try to answer the following questions:

- How easy was it for you to provide your conversational partner your full attention? When stray thoughts entered your head, how did you refocus yourself?

- Were you able to pay attention to your breathing while engaged in this conversation? Were you breathing lightly or heavily? Did your breathing get in the way of you listening mindfully? If yes, what happened?

- Did you attempt to empathize with your conversational partner? How easy was it to understand where they were coming from? Was it still easy to empathize if you didn’t agree with something they said or didn’t like something they said?

- How did your listening style impact your ability to stay mindful while listening? Do you think all four listening styles are suited for mindful listening? Why?

Key Takeaways

- Hearing happens when sound waves hit our eardrums. Listening involves processing these sounds into something meaningful.

- The listening process includes: having the motivation to listen, clearly hearing the message, paying attention, interpreting the message, evaluating the message, remembering and responding appropriately.

- There are many types of listening styles: comprehension, evaluative, empathetic, and appreciative.

Exercises

- Take the online hearing test. Go to: Hearing Test or the Audiogram on the MED-EL website. These are online tests. You should always consult a licensed audiologist if you have concerns about hearing loss.

- For the next week, do a listening diary. Take notes of all the things you listen to and analyze to see if you are truly a good listener. Do you ask people to repeat things? Do you paraphrase?

- After completing the Listening Styles Questionnaire, think about your own listening style and how it impacts how you interact with others. What should you think about when communicating with people who have a different listening style?

7.4 Listening Responses

Learning Objectives

- Discuss different types of listening responses.

- Discern different types of questioning.

- Analyze perception checking.

Who do you think is a great listener? Why did you name that particular person? How can you tell that person is a good listener? You probably recognize a good listener based on the nonverbal and verbal cues that they display. In this section, we will discuss different types of listening responses. We all don’t listen in the same way. Also, each situation is different and requires a distinct style that is appropriate for that situation.

Types of Listening Responses

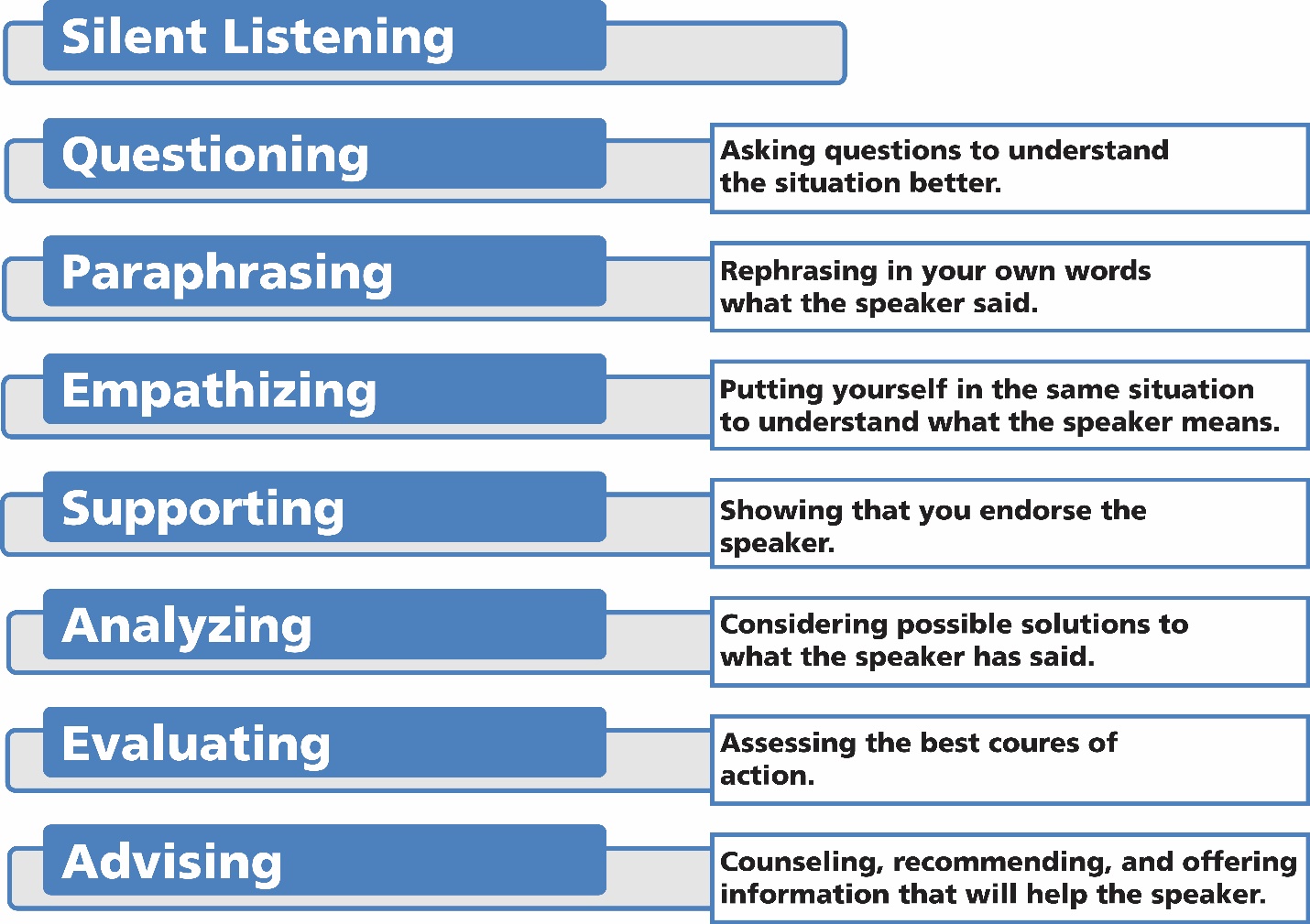

Ronald Adler, Lawrence Rosenfeld, and Russell Proctor are three interpersonal scholars who have done quite a bit with listening.52 Based on their research, they have found different types of listening responses: silent listening, questioning, paraphrasing, empathizing, supporting, analyzing, evaluating, and advising (Figure 7.6).53

Silent Listening

Silent listening occurs when you say nothing. It is ideal in certain situations and awful in other situations. However, when used correctly, it can be very powerful. If misused, you could give the wrong impression to someone. It is appropriate to use when you don’t want to encourage more talking. It also shows that you are open to the speaker’s ideas.

Sometimes people get angry when someone doesn’t respond. They might think that this person is not listening or trying to avoid the situation. But it might be due to the fact that the person is just trying to gather their thoughts, or perhaps it would be inappropriate to respond. There are certain situations such as in counseling, where silent listening can be beneficial because it can help that person figure out their feelings and emotions.

Questioning

In situations where you want to get answers, it might be beneficial to use questioning. You can do this in a variety of ways. There are several ways to question in a sincere, nondirective way (see Table 7.3):

| Reason | Example |

|---|---|

| To clarify meanings | A young child might mumble something and you want to make sure you understand what they said. |

| To learn about others’ thoughts, feelings, and wants (open/closed questions) | When you ask your partner where they see your relationship going in the next few years. |

| To encourage elaboration | Nathan says “That’s interesting!” Jonna has to ask him further if he means interesting in a positive or negative way. |

| To encourage discovery | Ask your parents how they met because you never knew. |

| To gather more facts and details | Police officers at the scene of the crime will question any witnesses to get a better understanding of what happened. |

Table 7.3 Types of Nondirective Questioning

You might have different types of questions. Sincere questions are ones that are created to find a genuine answer. Counterfeit questions are disguised attempts to send a message, not to receive one. Sometimes, counterfeit questions can cause the listener to be defensive. For instance, if someone asks you, “Tell me how often you used crystal meth.” The speaker implies that you have used meth, even though that has not been established. A speaker can use questions that make statements by emphasizing specific words or phrases, stating an opinion or feeling on the subject. They can ask questions that carry hidden agendas, like “Do you have $5?” because the person would like to borrow that money. Some questions seek “correct” answers. For instance, when a friend says, “Do I look fat?” You probably have a correct or ideal answer. There are questions that are based on unchecked assumptions. An example would be, “Why aren’t you listening?” This example implies that the person wasn’t listening, when in fact they are listening.

Paraphrasing

Paraphrasing is defined as restating in your own words, the message you think the speaker just sent. There are three types of paraphrasing. First, you can change the speaker’s wording to indicate what you think they meant. Second, you can offer an example of what you think the speaker is talking about. Third, you can reflect on the underlying theme of a speaker’s remarks. Paraphrasing represents mindful listening in the way that you are trying to analyze and understand the speaker’s information. Paraphrasing can be used to summarize facts and to gain consensus in essential discussions. This could be used in a business meeting to make sure that all details were discussed and agreed upon. Paraphrasing can also be used to understand personal information more accurately. Think about being in a counselor’s office. Counselors often paraphrase information to understand better exactly how you are feeling and to be able to analyze the information better.

Empathizing

Empathizing is used to show that you identify with a speaker’s information. You are not empathizing when you deny others the rights to their feelings. Examples of this are statements such as, “It’s really not a big deal” or “Who cares?” This indicates that the listener is trying to make the speaker feel a different way. In minimizing the significance of the situation, you are interpreting the situation in your perspective and passing judgment.

Supporting

Sometimes, in a discussion, people want to know how you feel about them instead of a reflection on the content. Several types of supportive responses are: agreement, offers to help, praise, reassurance, and diversion. The value of receiving support when faced with personal problems is very important. This has been shown to enhance psychological, physical, and relational health. To effectively support others, you must meet certain criteria. You have to make sure that your expression of support is sincere, be sure that other person can accept your support, and focus on “here and now” rather than “then and there.”

Analyzing

Analyzing is helpful in gaining different alternatives and perspectives by offering an interpretation of the speaker’s message. However, this can be problematic at times. Sometimes the speaker might not be able to understand your perspective or may become more confused by accepting it. To avoid this, steps must be taken in advance. These include tentatively offering your interpretation instead of as an absolute fact. By being more sensitive about it, it might be more comfortable for the speaker to accept. You can also make sure that your analysis has a reasonable chance of being correct. If it were inaccurate, it would leave the person more confused than before. Also, you must make sure the person will be receptive to your analysis and that your motive for offering is to truly help the other person. An analysis offered under any other circumstances is useless.

Evaluating

Evaluating appraises the speaker’s thoughts or behaviors. The evaluation can be favorable (“That makes sense”) or negative (passing judgment). Negative evaluations can be critical or non-critical (constructive criticism). Two conditions offer the best chance for evaluations to be received: if the person with the problem requested an evaluation, and if it is genuinely constructive and not designed as a putdown.

Advising

Advising differs from evaluations. It is not always the best solution and can sometimes be harmful. In order to avoid this, you must make sure four conditions are present: be sure the person is receptive to your suggestions, make sure they are truly ready to accept it, be confident in the correctness of your advice, and be sure the receiver won’t blame you if it doesn’t work out.

Perception Checking

Perceptions change in a relationship. Initially, people can view others positively (for example, confident, thrifty, funny), then later in the relationship that person changes (arrogant, cheap, childish). The person hasn’t changed. Only our perceptions of them have changed. That is why we focus on perception in a communication book because often, our perception affects how we communicate. It also has an impact on what we listen to and how we listen. For instance, when people get married, one person might say, “I love you! I would die for you,” then a couple of years later, that same person might say, “I hate you! I am going to kill you!” Their perceptions about the other person will change.54

Even when people break up, men typically will think about the physical aspects of the relationship (I gave her a watch, she wasn’t that hot) and women will think about the emotional aspects of the relationship (I gave him my heart, I really cared about him.). Perception is an interesting thing because sometimes we think other people have a similar perspective, but as we will see, that is not always the case.

Selection

What we pay attention to varies from one person to another. The first step in the perception process is selection. It determines what things we focus on compared to what things we ignore. What we select to focus on depends on:

- Intensity – if it is bigger, brighter, louder in some way. Think about all the advertisements that you view. If the words are bigger or if the sound is louder, you are more likely to pay attention to it. Advertisers know that intensity is very important to get people to pay attention.

- Repetition–It has been said that to get someone to do something, they have to be told three different ways and three different times. People pay attention to things that repeat because you can remember it easier. In school, we learn to do things over and over again, because it teaches us mastery of a skill.

- Differences – We will pay attention to differences, especially if it is a disparity or dissimilarity to what commonly occurs. Think about changes or adjustments that you had to deal with in life. These transformations made you notice the comparisons. For instance, children who go through a divorce will talk about the differences that they encountered. Children will focus on how things are different and how it is not the same.

- Motives/Goals. We tend to pay attention to things for which have a strong interest or desire. If you love cars, you will probably notice cars more closely than someone else who has no interest in cars. Another example might be if you are single, then you might notice who is married and who is not more than someone in a committed relationship.

- Emotions. Our emotional state has a strong impact on how we view life in general. If we are sad, we will probably notice other sad faces. The same thing happens when we are happy; we will tend to notice other happy people. Our emotions can impact how we feel. If we are angry, we might say things we don’t mean and not perceive how we come across to other people.

Organization

The second phase in the perception process is organization, or how we arrange information in our minds. So, once we have selected what information we pay attention to, our minds try to process it. Sometimes when this occurs, we engage in stereotyping or attribute certain characteristics to a certain set of individuals. In other words, we classify or labels others based on certain qualities.

Also, when people organize information in their mind, they can also engage in punctuation, or establishing the effects and causes in communication behavior. It is more useful to realize that a conflict situation can be perceived differently by each person, and it is important to focus on “What we can do to make this situation better?”

Interpretation

The third phase of the perception process is interpretation. In this phase, we try to understand the information or make sense of it. This depends on a few factors:

- Degree of involvement–If we were in the middle of an accident, we would probably have more information regarding what event occurred compared to a bystander. The more involved we are with something, the more we can make sense of what is actually happening. For instance, in cults, the members understand the rules and rituals, but an outsider would not understand, because they are not exposed to the rules and rituals.

- Relational satisfaction – If we are happy in a relationship, we tend to think that everything is wonderful. However, if you are dissatisfied in the relationship, you might second guess the behaviors and actions of your partner.

- Past experiences – If you had a good past experience with a certain company, you might think that everything they do is wonderful. However, if your first experience was horrible, you may think that they are always horrible. In turn, you will interpret that company’s actions as justified because you already encountered a horrible experience.

- Assumptions about human behavior – If you believed that most people do not lie, then you would probably be very hurt if someone important to you lied to you. Our assumptions about others help us understand their behaviors and actions. If you had a significant other cheats on you, you would probably be suspicious of future interactions with other significant others.

- Expectations – Our behaviors are also influenced by our expectations of others. If we expect a party to be fun and it isn’t, then we will be let down. However, if we have no expectations about a party, it may not affect how we feel about it.

- Knowledge of others – If you know that someone close to you has a health problem, then it will not be a shock if they need medical attention. However, if you had no clue that this person was unhealthy, it would come as a complete surprise. How you interpret a given situation is oftentimes based on what you know about a certain situation. 55

Negotiation

The last phase of the perception process is called negotiation. In this phase, people are trying to understand what is happening. People often use narratives or stories to explain and depict their life. For instance, a disagreement between a teacher and student might look very different depending on which perspective you take. The student might perceive that they are hard-working and very studious. The student thinks they deserve a high grade. However, the teacher might feel that their job is to challenge all students to their highest levels and be fair to all students. By listening to both sides, we can better understand what is going on and what needs to be done in certain situations. Think about car accidents and how police officers have to listen to both sides. Police officers have to determine what happened and who is at fault. Sometimes it is not an easy task.

Influences on Perception

All of us don’t perceive the same things. One person might find something beautiful, but another person might think it is horrible. When it comes to our perception, there are four primary influences we should understand: physiological, psychological, social, and cultural.

Physiological Influences

Some of the reasons why we don’t interpret things, in the same way are due to physiology. Hence, biology has an impact on what we do and do not perceive. In this section, we will discuss the various physiological influences.

- Senses – Our senses can have an impact on what and where we focus our attention. For instance, if you have a strong sense of smell, you might be more sensitive to a foul-smelling odor compared to someone who cannot smell anything due to sinus problems. Our senses give us a different perception of the world.

- Age – Age can impact what we perceive. Have you ever noticed that children have so much energy, and the elderly do not? Children may perceive that there is so much to do in a day, and the elderly may perceive that there is nothing to do. Our age influences how we think about things.

- Health – when we are healthy, we have the stamina and endurance to do many things. However, when we are sick, our bodies may be more inclined to rest. Thus, we will perceive a lot of information differently. For instance, when you are healthy, some of your favorite meals will taste really good, but when you are sick, it might not taste so good, because you cannot smell things due to a stuffy nose.

- Hunger – When you are hungry, it is tough to concentrate on anything except food. Studies have shown that when people are hungry, all they focus on is something to eat.

- Biological cycles – Some people are “morning larks” and some are “night owls.” In other words, there are peaks where people perform at their highest level. For some individuals, it is late at night, and for others, it is early in the morning. When people perform at their peak times, they are likely to be more perceptive of information. If you are a person who loves getting up early, you would probably hate night classes, because you are not able to absorb as much information as you could if the class was in the morning.

Psychological Influences

Sometimes the influences on perception are not physiological but psychological. These influences include mood and self-concept. These influences are based in our mind, and we can’t detect them in others.

- Mood – Whether we are happy or sad can affect how we view the world. For instance, if we are happy, then anything that happens, we might view it more positively.

- Self-concept – If we have a healthy self-concept of ourselves, we may not be offended if someone makes a negative remark. Yet, if we have a poor self-concept of ourselves, then we are probably going to be more influenced by negative remarks. The stronger our self-concept is, the more likely it will affect how we view perceive other people’s communication behaviors toward us.

Social Influences

Social influences include sex and gender roles, as well as occupational roles. These roles can impact our perceptions. Because we are in these roles, we might be likely to think differently than others in different roles.

- Sex and gender roles – We have certain expectations in our culture regarding how men and women should behave in public. Women are expected to be more nurturing than men. Moreover, men and women are viewed differently concerning their marital status and age.

- Occupational roles – Our jobs have an influence on how we perceive the world. If you were a lawyer, you might be more inclined to take action on civil cases than your average member of the public, because you know how to handle these kinds of situations. Moreover, if you are a nurse or medical specialist, you are more likely to perceive the health of other individuals. You would be able to tell if someone needed urgent medical care or not.

Research Spotlight