3 Intrapersonal Communication

Jason S. Wrench; Narissra M. Punyanunt-Carter; and Katherine S. Thweatt

Who are you? Have you ever sat around thinking about how you fit into the larger universe. Manford Kuhn created a simple exercise to get at the heart of this question.1 Take out a piece of paper and number 1 to 20 (or use the worksheet in the workbook). For each number, answer the question “Who Am I?” using a complete sentence. Results from this activity generally demonstrate five distinct categories about an individual: social group an individual belongs to, ideological beliefs, personal interests, personal ambitions, and self-evaluations. If you did the Twenty Item Test, take a second and identify your list using this scheme. All of these five categories are happening at what is called the intrapersonal-level. Intrapersonal refers to something that exists or occurs within an individual’s self or mind. This chapter focuses on understanding intrapersonal processes and how they relate to communication.

Larry Barker and Gordon Wiseman created one of the oldest definitions of the term “intrapersonal communication” in the field of communication. Barker and Wiseman defined intrapersonal communication as “the creating, functioning, and evaluating of symbolic processes which operate primarily within oneself.”2 The researchers go on to explain that intrapersonal communication exists on a continuum from thinking and reflecting (more internal) to talking aloud or writing a note to one’s self (more external).

More recently, Samuel Riccillo defined intrapersonal communication as a “process involving the activity of the individual biological organism’s capacity to coordinate and organize complex actions of an intentional nature… For the human organism, such complex interactions are anchored in the signaling processes known as symbolic language.”3 Both the Barker and Wiseman and the Riccillo definitions represent two ends of the spectrum with regards to the idea of intrapersonal communication. For our purposes in this book, we define intrapersonal communication as something of a hybrid between these two definitions. Intrapersonal communication refers to communication phenomena that exist within or occurs because of an individual’s self or mind. Under this definition, we can examine Barker and Wiseman’s notions of both ends of their intrapersonal communication continuum while also realizing that Riccillo’s notions of biology (e.g., personality and communication traits) are equally important.

3.1 Who Are You?

Learning Objectives

- Differentiate between self-concept and self-esteem.

- Explain what is meant by Charles Horton Cooley’s concept of the looking-glass self.

- Examine the impact that self-esteem has on communication.

In the first part of this chapter, we mentioned Manford Kuhn’s “Who Am I?” exercise for understanding ourselves. A lot of the items generally listed by individuals completing this exercise can fall into the areas of self-concept and self-esteem. In this section, we’re going to examine both of these concepts.

Self-Concept

According to Roy F. Baumeister (1999), self-concept implies “the individual’s belief about himself or herself, including the person’s attributes and who and what the self is.”4 An attribute is a characteristic, feature, or quality or inherent part of a person, group, or thing. In 1968, social psychologist Norman Anderson came up with a list of 555 personal attributes.5 He had research participants rate the 555 attributes from most desirable to least desirable. The top ten most desirable characteristics were:

- Sincere

- Honest

- Understanding

- Loyal

- Truthful

- Trustworthy

- Intelligent

- Dependable

- Open-Minded

- Thoughtful

Conversely, the top ten least desirable attributes were:

- Liar

- Phony

- Mean

- Cruel

- Dishonest

- Untruthful

- Obnoxious

- Malicious

- Dishonorable

- Deceitful

When looking at this list, do you agree with the ranks from 1968? In a more recent study, conducted by Jesse Chandler using an expanded list of 1,042 attributes,6 the following pattern emerged for the top 10 most positively viewed attributes:

- Honest

- Likable

- Compassionate

- Respectful

- Kindly

- Sincere

- Trustworthy

- Ethical

- Good-Natured

- Honorable

And here is the updated list for the top 10 most negatively viewed attributes:

- Pedophilic

- Homicidal

- Evil-Doer

- Abusive

- Evil-Minded

- Nazi

- Mugger

- Asswipe

- Untrustworthy

- Hitlerish

Some of the changes in both lists represent changing times and the addition of the new terms by Chandler. For example, the terms sincere, honest, and trustworthy were just essential attributes for both the 1968 and 2018 studies. Conversely, none of the negative attributes remained the same from 1968 to 2018. The negative attributes, for the most part, represent more modern sensibilities about personal attributes.

The Three Selves

Carl Rogers, a distinguished psychologist in the humanistic approach to psychology, believed that an individual’s self-concept is made of three distinct things: self-image, self-worth, and ideal-self.7

Self-Image

An individual’s self-image is a view that they have of themselves. If we go back and look at the attributes that we’ve listed in this section, think about these as laundry lists of possibilities that impact your view of yourself. For example, you may view yourself as ethical, trustworthy, honest, and loyal, but you may also realize that there are times when you are also obnoxious and mean. For a positive self-image, we will have more positive attributes than negative ones. However, it’s also possible that one negative attribute may overshadow the positive attributes, which is why we also need to be aware of our perceptions of our self-worth.

Self-Worth

Self-worth is the value that you place on yourself. In essence, self-worth is the degree to which you see yourself as a good person who deserves to be valued and respected. Unfortunately, many people judge their self-worth based on arbitrary measuring sticks like physical appearance, net worth, social circle/clique, career, grades, achievements, age, relationship status, likes on Facebook, social media followers, etc.… Interested in seeing how you view your self-worth? Then take a minute and complete the Contingencies of Self-Worth Scale.8 According to Courtney Ackerman, there are four things you can do to help improve your self-worth:9

- You no longer need to please other people.

- No matter what people do or say, and regardless of what happens outside of you, you alone control how you feel about yourself.

- You have the power to respond to events and circumstances based on your internal sources, resources, and resourcefulness, which are the reflection of your true value.

- Your value comes from inside, from an internal measure that you’ve set for yourself.

Ideal-Self

The final characteristic of Rogers’ three parts to self-concept is the ideal-self.10 The ideal-self is the version of yourself that you would like to be, which is created through our life experiences, cultural demands, and expectations of others. The real-self, on the other hand, is the person you are. The ideal-self is perfect, flawless, and, ultimately, completely unrealistic. When an individual’s real-self and ideal-self are not remotely similar, someone needs to think through if that idealized version of one’s self is attainable. It’s also important to know that our ideal-self is continuously evolving. How many of us wanted to be firefighters, police officers, or astronauts as kids? Some of you may still want to be one of these, but most of us had our ideal-self evolve.

Three Self’s Working Together

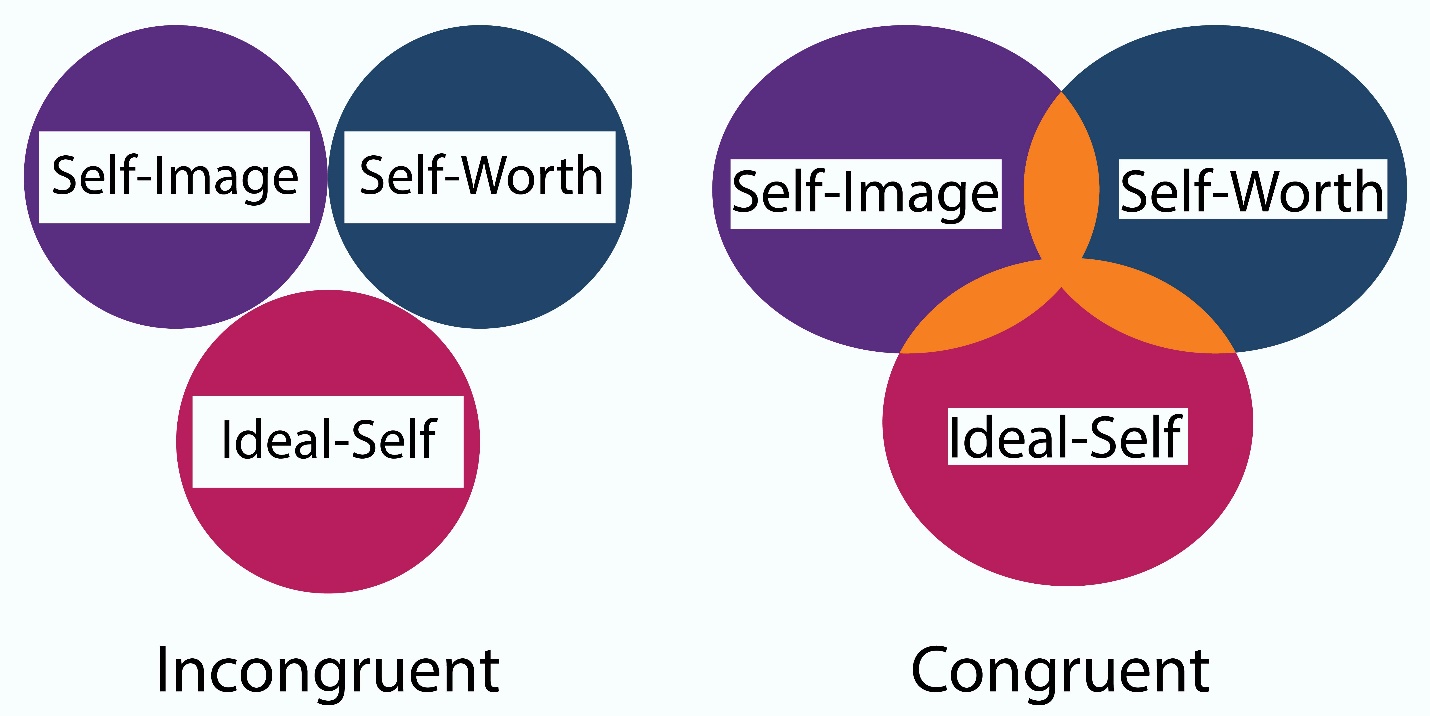

Now that we’ve looked at the three parts of Carl Rogers’ theory of self-concept, let’s discuss how they all work together to create one’s self-concept. Rogers’ theory of self-concept also looks at a concept we discussed in Chapter 2 when we discussed Abraham Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs. Specifically, the idea of self-actualization. In Rogers’ view, self-actualization cannot happen when an individual’s self-image, self-worth, and ideal-self have no overlap.

As you can see in Figure 3.1, on the left side, you have the three parts of self-concept as very distinct in this individual, which is why it’s called incongruent, or the three are not compatible with each other. In this case, someone’s self-image and ideal-self may have nothing in common, and this person views themself as having no self-worth. When someone has this type of incongruence, they are likely to exhibit other psychological problems. On the other hand, when someone’s self-image, ideal-self, and self-worth overlap, that person is considered congruent because the three parts of self-concept overlap and are compatible with each other. The more this overlap grows, the greater the likelihood someone will be able to self-actualize. Rogers believed that self-actualization was an important part of self-concept because until a person self-actualizes, then he/she/they will be out of balance with how he/she/they relate to the world and with others.

The “Looking-Glass” Self

In 1902, Charles Horton Cooley wrote Human Nature and the Social Order. In this book, Cooley introduced a concept called the looking-glass self: “Each to each a looking-glass / Reflects the other that doth pass”11 Although the term “looking-glass” isn’t used very often in today’s modern tongue, it means a mirror. Cooley argues, when we are looking to a mirror, we also think about how others view us and the judgments they make about us. Cooley ultimately posed three postulates:

- Actors learn about themselves in every situation by exercising their imagination to reflect on their social performance.

- Actors next imagine what those others must think of them. In other words, actors imagine the others’ evaluations of the actor’s performance.

- The actor experiences an affective reaction to the imagined evaluation of the other.12

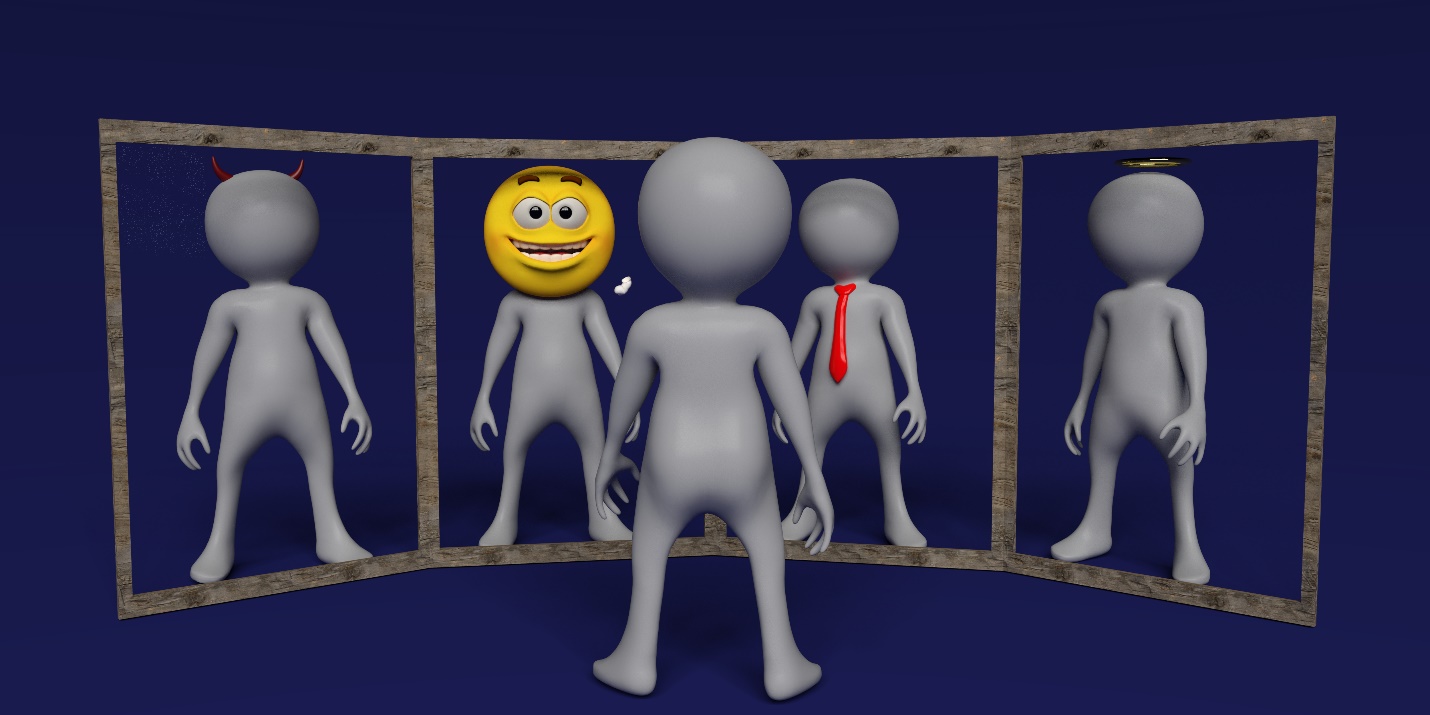

In Figure 3.2, we see an illustration of this basic idea. You have a figure standing before four glass panes. In the left-most mirror, the figure has devil horns; in the second, a pasted on a fake smile; in the third, a tie; and in the last one, a halo. Maybe the figure’s ex sees the devil, his friends and family think the figure is always happy, the figure’s coworkers see a professional, and the figure’s parents/guardians see their little angel. Along with each of these ideas, there are inherent judgments. And, not all of these judgments are necessarily accurate, but we still come to understand and know ourselves based on our perceptions of these judgments.

Ultimately, our self-image is shaped through our interactions with others, but only through the mediation of our minds. At the same time, because we perceive that others are judging us, we also tend to shape our façade to go along with that perception. For example, if you work in the customer service industry, you may sense that you are always expected to smile. Since you want to be viewed positively, you plaster on a fake smile all the time no matter what is going on in your personal life. At the same time, others may start to view you as a happy-go-lucky person because you’re always in a good mood.

Thankfully, we’re not doing this all the time, or we would be driving ourselves crazy. Instead, there are certain people in our lives about whose judgments we worry more than others. Imagine you are working in a new job. You respect your new boss, and you want to gain her/his/their respect in return. Currently, you believe that your boss doesn’t think you’re a good fit for the organization because you are not serious enough about your job. If you perceive that your boss will like you more if you are a more serious worker, then you will alter your behavior to be more in line with what your boss sees as “serious.” In this situation, your boss didn’t come out and say that you were not a serious worker, but we perceived the boss’ perception of us and her/his/their judgment of that perception of us and altered our behavior to be seen in a better light.

Self-Esteem

One of the most commonly discussed intrapersonal communication ideas is an individual’s self-esteem. There are a ton of books in both academic and non-academic circles that address this idea.

Defining Self-Esteem

Self-esteem is an individual’s subjective evaluation of her/his/their abilities and limitations. Let’s break down this definition into sizeable chunks.

Subjective Evaluation

The definition states that someone’s self-esteem is an “individual’s subjective evaluation.” The word “subjective” emphasizes that self-esteem is based on an individual’s emotions and opinions and is not based on facts. For example, many people suffer from what is called the impostor syndrome, or they doubt their accomplishments, knowledge, and skills, so they live in fear of being found out a fraud. These individuals have a constant fear that people will figure out that they are “not who they say they are.” Research in this area generally shows that these fears of “being found out” are not based on any kind of fact or evidence. Instead, these individuals’ emotions and opinions of themselves are fueled by incongruent self-concepts. Types of people who suffer from imposter syndrome include physicians, CEOs, academics, celebrities, artists, and pretty much any other category. Again, it’s important to remember that these perceptions are subjective and not based on any objective sense of reality. Imagine a physician who has gone through four years of college, three years of medical school, three years of residency, and another four years of specialization training only to worry that someone will find out that he/she/they aren’t that smart after all. There’s no objective basis for this perception; it’s completely subjective and flies in the face of facts.

In addition to the word “subjective,” we also use the word “evaluation” in the definition of self-esteem. By evaluation, we mean a determination or judgment about the quality, importance, or value of something. We evaluate a ton of different things daily:

- We evaluate how we interact with others.

- We evaluate the work we complete.

- We also evaluate ourselves and our specific abilities and limitations.

Our lives are filled with constant evaluations.

Abilities

When we discuss our abilities, we are referring to the acquired or natural capacity for specific talents, skills, or proficiencies that facilitate achievement or accomplishment. First, someone’s abilities can be inherent (natural) or they can be learned (acquired). For example, if someone is 6’6”, has excellent reflexes, and has a good sense of space, he/she/they may find that they have a natural ability to play basketball that someone who is 4’6”, has poor reflex speed, and has no sense of space simply does not have. That’s not to say that both people cannot play basketball, but they will both have different ability levels. They can both play basketball because they can learn skills necessary to play basketball: shooting the ball, dribbling, rules of the game, etc. In a case like basketball, professional-level players need to have a combination of both natural and acquired abilities.

We generally break abilities into two different categories: talent or skills to help distinguish what we are discussing. First, talent is usually more of an inherent or natural capacity. For example, someone may look like the ideal basketball player physically, but the person may simply have zero talent for the game. Sometimes we call talent the “it factor” because it’s often hard to pinpoint why someone people have it and others don’t. Second, skills refer to an individual’s use of knowledge or physical being to accomplish a specific task. We often think of skills in terms of the things we learn to do. For example, most people can learn to swim or ride a bike. Doing this may take some time to learn, but we can develop the skills necessary to stay afloat and move in the water or the skills necessary to achieve balance and pedal the bike.

The final part of the definition of abilities is the importance of achievement and accomplishment. Just because someone has learned the skills to do something does not mean that they can accomplish the task. Think back to when you first learned to ride a bicycle (or another task). Most of us had to try and try again before we found ourselves pedaling on our own without falling over. The first time you got on the bicycle and fell over, you didn’t have the ability to ride a bike. You may have had a general understanding of how it worked, but there’s often a massive chasm between knowing how something is done and then actually achieving or accomplishing it. As such, when we talk about abilities, we really emphasize the importance of successful completion.

Limitations

In addition to one’s abilities, it’s always important to recognize that we all have limitations. In the words of my podiatrist, I will never be a runner because of the shape of my arch. Whether I like it or not, my foot’s physical structure will not allow me to be an effective runner. Thankfully, this was never something I wanted to be. I didn’t sit up all night as a child dreaming of running a marathon one day. In this case, I have a natural limitation, but it doesn’t negatively affect me because I didn’t evaluate running positively for myself. On the flip side, growing up, I took years of piano lessons, but honestly, I was just never that good at it. I have short, stubby fingers, so reaching notes on a piano that are far away is just hard for me. To this day, I wish I was a good piano player. I am disappointed that I couldn’t be a better piano player. Now, does this limitation cripple me? No.

We all have limitations on what we can and cannot do. When it comes to your self-esteem, it’s about how you evaluate those limitations. Do you realize your limitations and they don’t bother you? Or do your limitations prevent you from being happy with yourself? When it comes to understanding limitations, it’s important to recognize the limitations that we can change and the limitations we cannot change. One problem that many people have when it comes to limitations is that they cannot differentiate between the types of limitations. If I had wanted to be a runner growing up and then suddenly found out that my dream wasn’t possible because of my feet, then I could go through the rest of my life disappointed and depressed that I’m not a runner. Even worse, I could try to force myself to into being a runner and cause long-term damage to my body.

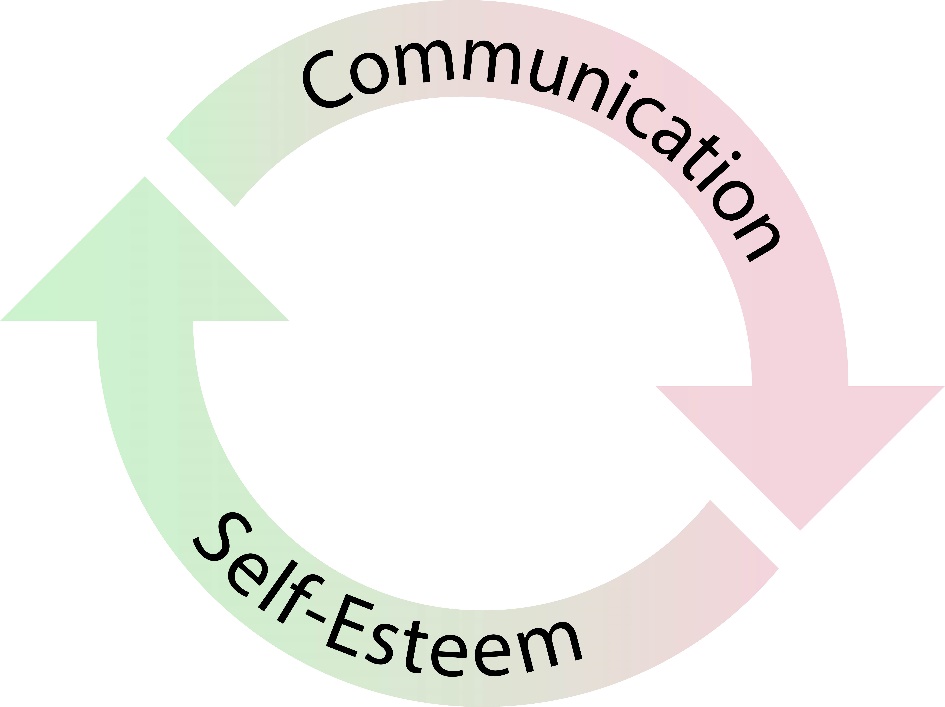

Self-Esteem and Communication

You may be wondering by this point about the importance of self-esteem in interpersonal communication. Self-esteem and communication have a reciprocal relationship (as depicted in Figure 3.3). Our communication with others impacts our self-esteem, and our self-esteem impacts our communication with others. As such, our self-esteem and communication are constantly being transformed by each other.

As such, interpersonal communication and self-esteem cannot be separated. Now, our interpersonal communication is not the only factor that impacts self-esteem, but interpersonal interactions are one of the most important tools we have in developing our selves.

Mindfulness Activity

One of the beautiful things about mindfulness is that it positively impacts someone’s self-esteem.13 It’s possible that people who are higher in mindfulness report higher self-esteem because of the central tenant of non-judgment. People with lower self-esteems often report highly negative views of themselves and their past experiences in life. These negative judgments can start to wear someone down.

One of the beautiful things about mindfulness is that it positively impacts someone’s self-esteem.13 It’s possible that people who are higher in mindfulness report higher self-esteem because of the central tenant of non-judgment. People with lower self-esteems often report highly negative views of themselves and their past experiences in life. These negative judgments can start to wear someone down.

Christopher Pepping, Analise O’Donovan, and Penelope J. Davis believe that mindfulness practice can help improve one’s self-esteem for four reasons:14

- Labeling internal experiences with words, which might prevent people from getting consumed by self-critical thoughts and emotions;

- Bringing a non-judgmental attitude toward thoughts and emotions, which could help individuals have a neutral, accepting attitude toward the self;

- Sustaining attention on the present moment, which could help people avoid becoming caught up in self-critical thoughts that relate to events from the past or future;

- Letting thoughts and emotions enter and leave awareness without reacting to them.15

For this exercise, think about a recent situation where you engaged in self-critical thoughts.

- What types of phrases ran through your head? Would you have said these to a friend? If not, why do you say them to yourself?

- What does the negative voice in your head sound like? Is this voice someone you want to listen to? Why?

- Did you try temporarily distracting yourself to see if the critical thoughts would go away (e.g., mindfulness meditation, coloring, exercise, etc.)? If yes, how did that help? If not, why?

- Did you examine the evidence? What proof did you have that the self-critical thought was true?

- Was this a case of a desire to improve yourself or a case of non-compassion towards yourself?

Self-Compassion

Some researchers have argued that self–esteem as the primary measure of someone’s psychological health may not be wise because it stems from comparisons with others and judgments. As such, Kristy Neff has argued for the use of the term self-compassion.16

Self-Compassion stems out of the larger discussion of compassion. Compassion then is about the sympathetic consciousness for someone who is suffering or unfortunate. Self-compassion “involves being touched by and open to one’s own suffering, not avoiding or disconnecting from it, generating the desire to alleviate one’s suffering and to heal oneself with kindness. Self-compassion also involves offering nonjudgmental understanding to one’s pain, inadequacies and failures, so that one’s experience is seen as part of the larger human experience.”18 Neff argues that self-compassion can be broken down into three distinct categories: self-kindness, common humanity, and mindfulness (Figure 3.4).

Self-Kindness

Humans have a really bad habit of beating ourselves up. As the saying goes, we are often our own worst enemies. Self-kindness is simply extending the same level of care and understanding to ourselves as we would to others. Instead of being harsh and judgmental, we are encouraging and supportive. Instead of being critical, we are empathic towards ourselves. Now, this doesn’t mean that we just ignore our faults and become narcissistic (excessive interest in oneself), but rather we realistically evaluate ourselves as we discussed in the Mindfulness Exercise earlier.

Common Humanity

The second factor of self-compassion is common humanity, or “seeing one’s experiences as part of the larger human experience rather than seeing them as separating and isolating.”19 As Kristen Naff and Christopher Germer realize, we’re all flawed works in progress.20 No one is perfect. No one is ever going to be perfect. We all make mistakes (some big, some small). We’re also all going to experience pain and suffering in our lives. Being self-compassionate is approaching this pain and suffering and seeing it for what it is, a natural part of being human. “The pain I feel in difficult times is the same pain you feel in difficult times. The circumstances are different, the degree of pain is different, but the basic experience of human suffering is the same.”21

Mindfulness

The final factor of self-compassion is mindfulness. Although Naff defines mindfulness in the same terms we’ve been discussing in this text, she specifically addresses mindfulness as a factor of pain, so she defines mindfulness, with regards to self-compassion, as “holding one’s painful thoughts and feelings in balanced awareness rather than over-identifying with them.”22 Essentially, Naff argues that mindfulness is an essential part of self-compassion, because we need to be able to recognize and acknowledge when we’re suffering so we can respond with compassion to ourselves.

Don’t Feed the Vulture

One area that we know can hurt someone’s self-esteem is what Sidney Simon calls “vulture statements.” According to Simon,

Vulture (‘vul-cher) noun. 1: any of various large birds of prey that are related to the haws, eagles and falcons, but with the head usually naked of feathers and that subsist chiefly or entirely on dead flesh.23

Unfortunately, all of us have vultures circling our heads or just sitting on our shoulders. In Figure 3.5, we see a young woman feeding an apple to her vulture. This apple represents all of the negative things we say about ourselves during a day. Many of us spend our entire days just feeding our vultures and feeding our vultures these self-deprecating, negative thoughts and statements. Admittedly, these negative thoughts “come from only one place. They grow out of other people’s criticisms, from the negative responses to what we do and say, and the way we act.”24 We have the choice to either let these thoughts consume us or fight them. According to Virginia Richmond, Jason Wrench, and Joan Gorham, the following are characteristic statements that vultures wait to hear so they can feed (see also Figure 3.6):

- Oh boy, do I look awful today; I look like I’ve been up all night.

- Oh, this is going to be an awful day.

- I’ve already messed up. I left my students’ graded exams at home.

- Boy, I should never have gotten out of bed this morning.

- Gee whiz. I did an awful job of teaching that unit.

- Why can’t I do certain things as well as Mr. Smith next door?

- Why am I always so dumb?

- I can’t believe I’m a teacher; why, I have the mentality of a worm.

- I don’t know why I ever thought I could teach.

- I can’t get anything right.

- Good grief, what am I doing here? Why didn’t I select any easy job?

- I am going nowhere, doing nothing; I am a failure at teaching.

- In fact, I am a failure in most things I attempt.25

Do any of these vulture statements sound familiar to you? If you’re like us, I’m sure they do. Part of self-compassion is learning to recognize these vulture statements when they appear in our minds and evaluate them critically. Ben Martin proposes four ways to challenging vulture statements (negative self-talk):

- Reality testing

- What is my evidence for and against my thinking?

- Are my thoughts factual, or are they just my interpretations?

- Am I jumping to negative conclusions?

- How can I find out if my thoughts are actually true?

- Look for alternative explanations

- Are there any other ways that I could look at this situation?

- What else could this mean?

- If I were being positive, how would I perceive this situation?

- Putting it in perspective

- Is this situation as bad as I am making out to be?

- What is the worst thing that could happen? How likely is it?

- What is the best thing that could happen?

- What is most likely to happen?

- Is there anything good about this situation?

- Will this matter in five years?

- Using goal-directed thinking

- Is thinking this way helping me to feel good or to achieve my goals?

- What can I do that will help me solve the problem?

- Is there something I can learn from this situation, to help me do it better next time?26

So, next time those vultures start circling you, check that negative self-talk. When we can stop these patterns of negativity towards ourselves and practice self-compassion, we can start plucking the feathers of those vultures. The more we treat ourselves with self-compassion and work against those vulture statements, the smaller and smaller those vultures get. Our vultures may never die, but we can make them much, much smaller.

Research Spotlight

In 2018, Laura Umphrey and John Sherblom examined the relationship between social communication competence, self-compassion, and hope. The goal of the study was to see if someone’s social communication competence could predict their ability to engage in self-compassion. Ultimately, the researchers found individuals who engaged in socially competent communication behaviors were more likely to engage in self-compassion, which “suggests that a person who can learn to speak with others competently, initiate conversations, engage others in social interaction, and be more outgoing, while managing verbal behavior and social roles, may also experience greater personal self-compassion” (p. 29).

In 2018, Laura Umphrey and John Sherblom examined the relationship between social communication competence, self-compassion, and hope. The goal of the study was to see if someone’s social communication competence could predict their ability to engage in self-compassion. Ultimately, the researchers found individuals who engaged in socially competent communication behaviors were more likely to engage in self-compassion, which “suggests that a person who can learn to speak with others competently, initiate conversations, engage others in social interaction, and be more outgoing, while managing verbal behavior and social roles, may also experience greater personal self-compassion” (p. 29).

Umphrey, L. R., & Sherblom, J. C. (2018). The constitutive relationship of social communication competence to self-compassion and hope. Communication Research Reports, 35(1), 22–32. https://doi.org/10.1080/08824096.2017.1361395

Key Takeaways

- Self-concept is an individual’s belief about themself, including the person’s attributes and who and what the self is. Conversely, self-esteem is an individual’s subjective evaluation of their abilities and limitations.

- Sociologist Charles Horton Cooley coined the term “looking-glass self” to refer to the idea that an individual’s self-concept is a reflection of how an individual imagines how he or she appears to other people. In other words, humans are constantly comparing themselves to how they believe others view them.

- There is an interrelationship between an individual’s self-esteem and her/his/their communication. In essence, an individual’s self-esteem impacts how they communicate with others, and this communication with others impacts their self-esteem.

Exercises

- Pull out a piece of paper and conduct the “Who Am I?” exercise created by Manford Kuhn. Once you have completed the exercise, categorize your list using Kuhn’s five distinct categories about an individual: social group an individual belongs to, ideological beliefs, personal interests, personal ambitions, and self-evaluations. After categorizing your list, ask yourself what your list says about your self-concept, self-image, self-esteem, and self-respect.

- Complete the Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale (http://www.wwnorton.com/college/psych/psychsci/media/rosenberg.htm). After getting your results, do you agree with your results? Why or why not? Why do you think you scored the way you did on the measure?

3.2 Personality and Perception in Intrapersonal Communication

Learning Objectives

- Define and differentiate between the terms personality and temperament.

- Explain common temperament types seen in both research and pop culture.

- Categorize personality traits as either cognitive dispositions or personal-social dispositions.

After the previous discussions of self-concept, self-image, and self-esteem, it should be obvious that the statements and judgments of others and your view of yourself can affect your communication with others. Additional factors, such as your personality and perception, affect communication as well. Let us next examine these factors and the influence each has on communication.

Personality

Personality is defined as the combination of traits or qualities—such as behavior, emotional stability, and mental attributes—that make a person unique. Before going further, let’s quickly examine some of the research related to personality. John Daly categorizes personality into four general categories: cognitive dispositions, personal-social dispositions, communicative dispositions, and relational dispositions.27 Before we delve into these four categories of personality, let’s take a quick look at two common themes in this area of research: nature or nurture and temperament.

Nature or Nurture

One of the oldest debates in the area of personality research is whether a specific behavior or thought process occurs within an individual because of their nature (genetics) or nurture (how he/she/they were raised). The first person to start investigating this phenomenon was Sir Francis Galton back in the 1870s.28 In 1875, Galton sought out twins and their families to learn more about similarities and differences. As a whole, Galton found that there were more similarities than differences: “There is no escape from the conclusion that nature prevails enormously over nurture when the differences of nurture do not exceed what is commonly to be found among persons of the same rank of society and in the same country.”29 However, the reality is that Galton’s twin participants had been raised together, so parsing out nature and nurture (despite Galton’s attempts) wasn’t completely possible. Although Galton’s anecdotes provided some interesting stories, that’s all they amounted to.

Minnesota Twins Raised Apart

So, how does one determine if something ultimately nature or nurture? The next breakthrough in this line of research started in the late 1970s when Thomas J. Bouchard and his colleagues at Minnesota State University began studying twins who were raised separately.30 This research started when a pair of twins, Jim Lewis and Jim Springer, were featured in an article on February 19, 1979, in the Lima News in Lima, Ohio.31 Jim and Jim were placed in an adoption agency and separated from each other at four weeks of age. They grew up just 40 miles away from each other, but they never knew the other one existed. Jess and Sarah Springer and Ernest and Lucille Lewis were looking to adopt, and both sets of parents were told that their Jim had been a twin, but they were also told that his twin had died. Many adoption agencies believed that placing twins with couples was difficult, so this practice of separating twins at birth was an inside practice that the adoptive parents knew nothing about. Jim Lewis’ mother had found out that Jim’s twin was still alive when he was toddler, so Jim Lewis knew that he had a twin but didn’t seek him out until he was 39 years old. Jim Springer, on the other hand, learned that he had been a twin when he was eight years old, but he believed the original narrative that his twin had died.

As you can imagine, Jim Springer was pretty shocked when he received a telephone message with his twin’s contact information out of nowhere one day. The February 19th article in the Lima News was initially supposed to be a profile piece on one of the Springers’ brothers, but the reporter covering the wedding found Lewis and Springer’s tale fascinating. The reporter found several striking similarities between the twins:32

- Their favorite subject in school was math

- Both hated spelling in school

- Their favorite vacation spot was Pas Grille Beach in Florida

- Both had previously been in law enforcement

- They both enjoyed carpentry as a hobby

- Both were married to women named Betty

- Both were divorced from women named Linda

- Both had a dog named “Toy”

- Both started suffering from tension headaches when they were 18

- Even their sons’ names were oddly similar (James Alan and James Allan)

This sensationalist story caught the attention of Bouchard because this opportunity allowed him and his colleagues to study the influence rearing had on twins in a way that wasn’t possible when studying twins who were raised together.

Over the next decade, Bouchard and his team of researchers would seek out and interview over 100 different pairs of twins or sets of triplets who had been raised apart.33 The researchers were able to compare those twins to twins who were reared together. As a whole, they found more similarities between the two twin groups than they found differences. This set of studies is one of many that have been conducted using twins over the years to help us understand the interrelationship between rearing and genetics.

Twin Research in Communication

In the field of communication, the first major twin study published was conducted by Cary Wecht Horvath in 1995.34 In her study, Horvath compared 62 pairs of identical twins and 42 pairs of fraternal twins to see if they differed in terms of their communicator style, or “the way one verbally, nonverbally, and paraverbally interacts to signal how literal meaning should be taken, filtered, or understood.”35 Ultimately, Horvath found that identical twins’ communicator styles were more similar than those of fraternal twins. Hence, a good proportion of someone’s communicator style appears to be a result of someone’s genetic makeup. However, this is not to say that genetics was the only factor at play about someone’s communicator style.

Other research in the field of communication has examined how a range of different communication variables are associated with genetics when analyzed through twin studies:36,37, 38

- Interpersonal Affiliation

- Aggressiveness

- Social Anxiety

- Audience Anxiety

- Self-Perceived Communication Competence

- Willingness to Communicate

- Communicator Adaptability

It’s important to realize that the authors of this book do not assume nor promote that all of our communication is biological. Still, we also cannot dismiss the importance that genetics plays in our communicative behavior and development. Here is our view of the interrelationship among environment and genetics. Imagine we have two twins that were separated at birth. One twin is put into a middle-class family where she will be exposed to a lot of opportunities. The other twin, on the other hand, was placed with a lower-income family where the opportunities she will have in life are more limited. The first twin goes to a school that has lots of money and award-winning teachers. The second twin goes to an inner-city school where there aren’t enough textbooks for the students, and the school has problems recruiting and retaining qualified teachers. The first student has the opportunity to engage in a wide range of extracurricular activities both in school (mock UN, debate, student council, etc.) and out of school (traveling softball club, skiing, yoga, etc.). The second twin’s school doesn’t have the budget for extracurricular activities, and her family cannot afford out of school activities, so she ends up taking a job when she’s a teenager. Now imagine that these twins are naturally aggressive. The first twin’s aggressiveness may be exhibited by her need to win in both mock UN and debate; she may also strive to not only sit on the student council but be its president. In this respect, she demonstrates more prosocial forms of aggression. The second twin, on the other hand, doesn’t have these more prosocial outlets for her aggression. As such, her aggression may be demonstrated through more interpersonal problems with her family, teachers, friends, etc.… Instead of having those more positive outlets for her aggression, she may become more physically aggressive in her day-to-day life. In other words, we do believe that the context and the world where a child is reared is very important to how they display communicative behaviors, even if those communicative behaviors have biological underpinnings.

Temperament Types

Temperament is the genetic predisposition that causes an individual to behave, react, and think in a specific manner. The notion that people have fundamentally different temperaments dates back to the Greek physician Hippocrates, known today as the father of medicine, who first wrote of four temperaments in 370 BCE: Sanguine, Choleric, Phlegmatic, and Melancholic. Although closely related, temperament and personality refer to two different constructs. Jan Strelau explains that temperament and personality differ in five specific ways:

- Temperament is biologically determined where personality is a product of the social environment.

- Temperamental features may be identified from early childhood, whereas personality is shaped in later periods of development.

- Individual differences in temperamental traits like anxiety, extraversion-introversion, and stimulus-seeking are also observed in animals, whereas personality is the prerogative of humans.

- Temperament stands for stylistic aspects. Personality for the content aspect of behavior.

- Unlike temperament, personality refers to the integrative function of human behavior.39

In 1978, David Keirsey developed the Keirsey Temperament Sorter, a questionnaire that combines the Myers-Briggs Temperament Indicator with a model of four temperament types developed by psychiatrist Ernst Kretschmer in the early 20th century.40 Take a minute and go to David Keirsey’s website and complete his four-personality type questionnaire (http://www.keirsey.com/sorter/register.aspx). You’ll also be able to learn a lot more about the four-type personality system.

In reality, there are a ton of four-type personality systems that have been created over the years. Table 3.1 provides just a number of the different four-type personality system that are available on the market today. Each one has its quirks and patterns, but the basic results are generally the same.

Table 3.1. Comparing 4-Personality Types

And before you ask, none of the research examining the four types has found clear sex differences among the patterns. Females and males are seen proportionately in all four categories.

For example, training publisher HRDQ publishes the “What’s My Style?” series (http://www.hrdqstore.com/Style), and has applied the four-personalities to the following workplace issues: coaching, communication, leadership, learning, selling, teams, and time management.

David Keirsey argues that the consistent use of the four temperament types (whatever terms we use) is an indication of the long-standing tradition and complexity of these ideas.41

The Big Five

In the world of personality, one of the most commonly discussed concepts in research is the Big Five. In the late 1950s, Ernest C. Tupes and Raymond E. Christal conducted a series of studies examining a model of personality.42,43 Ultimately, they found five consistent personality clusters they labeled: surgency, agreeableness, dependability, emotional stability, and culture). Listed below are the five broad personality categories with the personality trait words in parentheses that were associated with these categories:

- Surgency (silent vs. talkative; secretive vs. frank; cautious vs. adventurous; submissive vs. assertive; and languid, slow vs. energetic)

- Agreeableness (spiteful vs. good-natured; obstructive vs. cooperative; suspicious vs. trustful; rigid vs. adaptable; cool, aloof vs. attentive to people; jealous vs. not so; demanding vs. emotionally mature; self-willed vs. mild; and hard, stern vs. kindly)

- Dependability (frivolous vs. responsible and unscrupulous vs. conscientious; indolent vs. insistently orderly; quitting vs. persevering; and unconventional vs. conventional)

- Emotional Stability (worrying, anxious vs. placid; easily upset vs. poised, tough; changeable vs. emotionally stable; neurotic vs. not so; hypochondriacal vs. not so; and emotional vs. calm)

- Culture (boorish vs. intellectual, cultured; clumsy, awkward vs. polished; immature vs. independent-minded; lacking artistic feelings vs. esthetically fastidious, practical, logical vs. imaginative)

Although Tupes and Christal were first, they were not the only psychologists researching the idea of personality clusters.

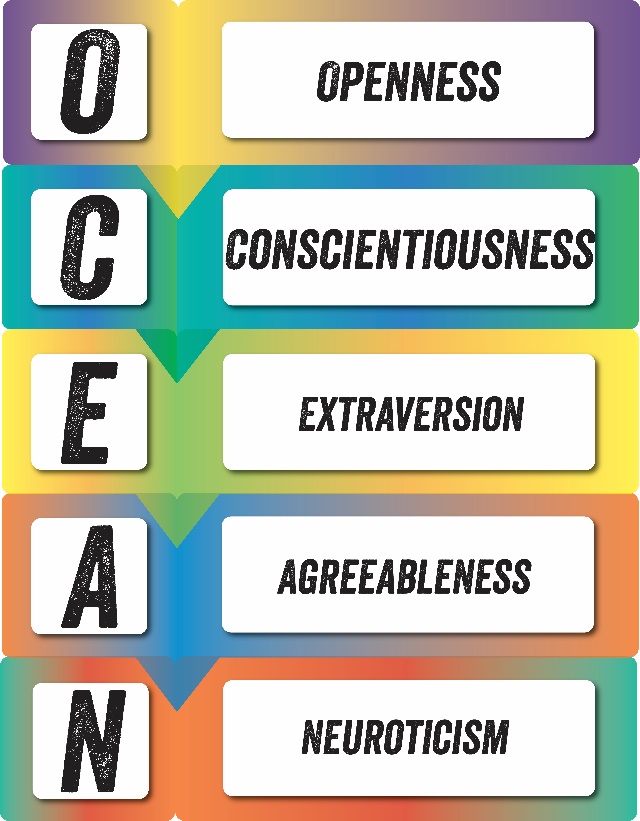

Two other researchers, Robert R. McCrae and Paul T. Costa, expanded on Tupes and Christal’s work to create the OCEAN Model of personality. McCrae and Costa originally started examining just three parts of the model, openness, neuroticism, and extroversion,44 but the model was later expanded to include both conscientiousness and agreeableness (Figure 3.7).45 Before progressing forward, take a minute and complete one of the many different freely available tests of the Five Factor Model of Personality:

- https://projects.fivethirtyeight.com/personality-quiz/,

- https://openpsychometrics.org/tests/IPIP-BFFM/,

- https://www.123test.com/personality-test/,

- https://www.idrlabs.com/big-five-subscales/test.php

Openness

Openness refers to “openness to experience,” or the idea that some people are more welcoming of new things. These people are willing to challenge their underlying life assumptions and are more likely to be amenable to differing points of view. Table 3.2 explores some of the traits associated with having both high levels of openness and having low levels of openness.

| High Openness | Low Openness |

|---|---|

| Original | Conventional |

| Creative | Down to Earth |

| Complex | Narrow Interests |

| Curious | Unadventurous |

| Prefer Variety | Conforming |

| Independent | Traditional |

| Liberal | Unartistic |

Table 3.2. Openness

Conscientiousness

Conscientiousness is the degree to which an individual is aware of their actions and how their actions impact other people. Table 3.3 explores some of the traits associated with having both high levels of conscientiousness and having low levels of conscientiousness.

| High Conscientiousness | Low Conscientiousness |

|---|---|

| Careful | Negligent |

| Reliable | Disorganized |

| Hard-Working | Impractical |

| Self-Disciplined | Thoughtless |

| Punctual | Playful |

| Deliberate | Quitting |

| Knowledgeable | Uncultured |

Table 3.3. Conscientiousness

Extraversion

Extraversion is the degree to which someone is sociable and outgoing. Table 3.4 explores some of the traits associated with having both high levels of extraversion and having low levels of extraversion.

| High Extraversion | Low Extraversion |

|---|---|

| Sociable | Sober |

| Fun Loving | Reserved |

| Friendly | Quiet |

| Talkative | Unfeeling |

| Warm | Lonely |

| Person-Oriented | Task-Oriented |

| Dominant | Timid |

Table 3.4. Extraversion

Agreeableness

Agreeableness is the degree to which someone engages in prosocial behaviors like altruism, cooperation, and compassion. Table 3.5 explores some of the traits associated with having both high levels of agreeableness and having low levels of agreeableness.

| High Agreeableness | Low Agreeableness |

|---|---|

| Good-Natured | Irritable |

| Soft Hearted | Selfish |

| Sympathetic | Suspicious |

| Forgiving | Critical |

| Open-Minded | Disagreeable |

| Flexible | Cynical |

| Humble | Manipulative |

Table 3.5. Agreeableness

Neuroticism

Neuroticism is the degree to which an individual is vulnerable to anxiety, depression, and emotional instability. Table 3.6 explores some of the traits associated with having both high levels of neuroticism and having low levels of neuroticism.

| High Neuroticism | Low Neuroticism |

|---|---|

| Nervous | Calm |

| High-Strung | Unemotional |

| Impatient | Secure |

| Envious/Jealous | Comfortable |

| Self-Conscious | Not impulse ridden |

| Temperamental | Hardy |

| Subjective | Relaxed |

Table 3.6. Neuroticism

Research Spotlight

In 2018, Yukti Mehta and Richard Hicks set out to examine the relationship between the Big Five Personality Types (openness, conscientiousness, agreeableness, extroversion, & neuroticism) and the Five Facets of Mindfulness Measure (observation, description, aware actions, non-judgmental inner experience, & nonreactivity). For the purposes of this study, the researchers collapsed the five facets of mindfulness into a single score. The researchers found that openness, conscientiousness, agreeableness, and extroversion were positively related to mindfulness, but neuroticism was negatively related to mindfulness.

In 2018, Yukti Mehta and Richard Hicks set out to examine the relationship between the Big Five Personality Types (openness, conscientiousness, agreeableness, extroversion, & neuroticism) and the Five Facets of Mindfulness Measure (observation, description, aware actions, non-judgmental inner experience, & nonreactivity). For the purposes of this study, the researchers collapsed the five facets of mindfulness into a single score. The researchers found that openness, conscientiousness, agreeableness, and extroversion were positively related to mindfulness, but neuroticism was negatively related to mindfulness.

Mehta, Y., & Hicks, R. E. (2018). The Big Five, mindfulness, and psychological wellbeing. Global Science and Technology Forum (GSTF) Journal of Psychology, 4(1). https://doi.org/10.5176/2345-7929_4.1.103

Cognitive Dispositions

Cognitive dispositions refer to general patterns of mental processes that impact how people respond and react to the world around them. These dispositions (or one’s natural mental or emotional outlook) take on several different forms. For our purposes, we’ll briefly examine the four identified by John Daly: locus of control, cognitive complexity, authoritarianism/dogmatism, and emotional intelligence.46

Locus of Control

One’s locus of control refers to an individual’s perceived control over their behavior and life circumstances. We generally refer to two different loci when discussing locus of control. First, we have people who have an internal locus of control. People with an internal locus of control believe that they can control their behavior and life circumstances. For example, people with an internal dating locus of control would believe that their dating lives are ultimately a product of their behaviors and decisions with regard to dating. In other words, my dating life exists because of my choices. The opposite of internal locus of control is the external locus of control, or the belief that an individual’s behavior and circumstances exist because of forces outside the individual’s control. An individual with an external dating locus of control would believe that their dating life is a matter of luck or divine intervention. This individual would also be more likely to blame outside forces if their dating life isn’t going as desired. We’ll periodically revisit locus of control in this text because of its importance in a wide variety of interpersonal interactions.

Cognitive Complexity

According to John Daly, cognitive “complexity has been defined in terms of the number of different constructs an individual has to describe others (differentiation), the degree to which those constructs cohere (integration), and the level of abstraction of the constructs (abstractiveness).”47 By differentiation, we are talking about the number of distinctions or separate elements an individual can utilize to recognize and interpret an event. For example, in the world of communication, someone who can attend to another individual’s body language to a great degree can differentiate large amounts of nonverbal data in a way to understand how another person is thinking or feeling. Someone low in differentiation may only be able to understand a small number of pronounced nonverbal behaviors.

Integration, on the other hand, refers to an individual’s ability to see connections or relationships among the various elements he or she has differentiated. It’s one thing to recognize several unique nonverbal behaviors, but it’s the ability to interpret nonverbal behaviors that enables someone to be genuinely aware of someone else’s body language. It would be one thing if I could recognize that someone is smiling, an eyebrow is going up, the head is tilted, and someone’s arms are crossed in front. Still, if I cannot see all of these unique behaviors as a total package, then I’m not going to be able to interpret this person’s actual nonverbal behavior.

The last part of Daly’s definition involves the ability to see levels of abstraction. Abstraction refers to something which exists apart from concrete realities, specific objects, or actual instances. For example, if someone to come right out and verbally tell you that he or she disagrees with something you said, then this person is concretely communicating disagreement, so as the receiver of the disagreement, it should be pretty easy to interpret the disagreement. On the other hand, if someone doesn’t tell you he or she disagrees with what you’ve said but instead provides only small nonverbal cues of disagreement, being able to interpret those theoretical cues is attending to communicative behavior that is considerably more abstract.

Overall, cognitive complexity is a critical cognitive disposition because it directly impacts interpersonal relationships. According to Brant Burleson and Scott Caplan,48 cognitive complexity impacts several interpersonal constructs:

- Form more detailed and organized impressions of others;

- Better able to remember impressions of others;

- Better able to resolve inconsistencies in information about others;

- Learn complex social information quickly; and

- Use multiple dimensions of judgment in making social evaluations.

In essence, these findings clearly illustrate that cognitive complexity is essential when determining the extent to which an individual can understand and make judgments about others in interpersonal interactions.

Authoritarianism/Dogmatism

According to Jason Wrench, James C. McCroskey, and Virginia Richmond, two personality characteristics that commonly impact interpersonal communication are authoritarianism and dogmatism.49 Authoritarianism is a form of social organization where individuals favor absolute obedience to authority (or authorities) as opposed to individual freedom. The highly authoritarian individual believes that individuals should just knowingly submit to their power. Individuals who believe in authoritarianism but are not in power believe that others should submit themselves to those who have power.

Dogmatism, although closely related, is not the same thing as authoritarianism. Dogmatism is defined as the inclination to believe one’s point-of-view as undeniably true based on faulty premises and without consideration of evidence and the opinions of others. Individuals who are highly dogmatic believe there is generally only one point-of-view on a specific topic, and it’s their point-of-view. Highly dogmatic individuals typically view the world in terms of “black and white” while missing most of the shades of grey that exist between. Dogmatic people tend to force their beliefs on others and refuse to accept any variation or debate about these beliefs, which can lead to strained interpersonal interactions. Both authoritarianism and dogmatism “tap into the same broad idea: Some people are more rigid than others, and this rigidity affects both how they communicate and how they respond to communication.”50

One closely related term that has received some minor exploration in interpersonal communication is right-wing authoritarianism. According to Bob Altemeyer in his book The Authoritarians (http://members.shaw.ca/jeanaltemeyer/drbob/TheAuthoritarians.pdf), right-wing authoritarians (RWAs) tend to have three specific characteristics:

- RWAs believe in submitting themselves to individuals they perceive as established and legitimate authorities.

- RWAs believe in strict adherence to social and cultural norms.

- RWAs tend to become aggressive towards those who do not submit to established, legitimate authorities and those who violate social and cultural norms.

Please understand that Altemeyer’s use of the term “right-wing” does not imply the same political connotation that is often associated with it in the United States. As Altemeyer explains, “Because the submission occurs to traditional authority, I call these followers right-wing authoritarians. I’m using the word “right” in one of its earliest meanings, for in Old English ‘right’(pronounced ‘writ’) as an adjective meant lawful, proper, correct, doing what the authorities said of others.”51 Under this definition, right-wing authoritarianism is the perfect combination of both dogmatism and authoritarianism.

Right-wing authoritarianism has been linked to several interpersonal variables. For example, parents/guardians who are RWAs are more likely to believe in a highly dogmatic approach to parenting. In contrast, those who are not RWAs tend to be more permissive in their approaches to parenting.52 Another study found that men with high levels of RWA were more likely to have been sexually aggressive in the past and were more likely to report sexually aggressive intentions for the future.53 Men with high RWA scores tend to be considerably more sexist and believe in highly traditional sex roles, which impacts how they communicate and interact with women.54 Overall, RWA tends to negatively impact interpersonal interactions with anyone who does not see an individual’s specific world view and does not come from their cultural background.

Emotional Intelligence

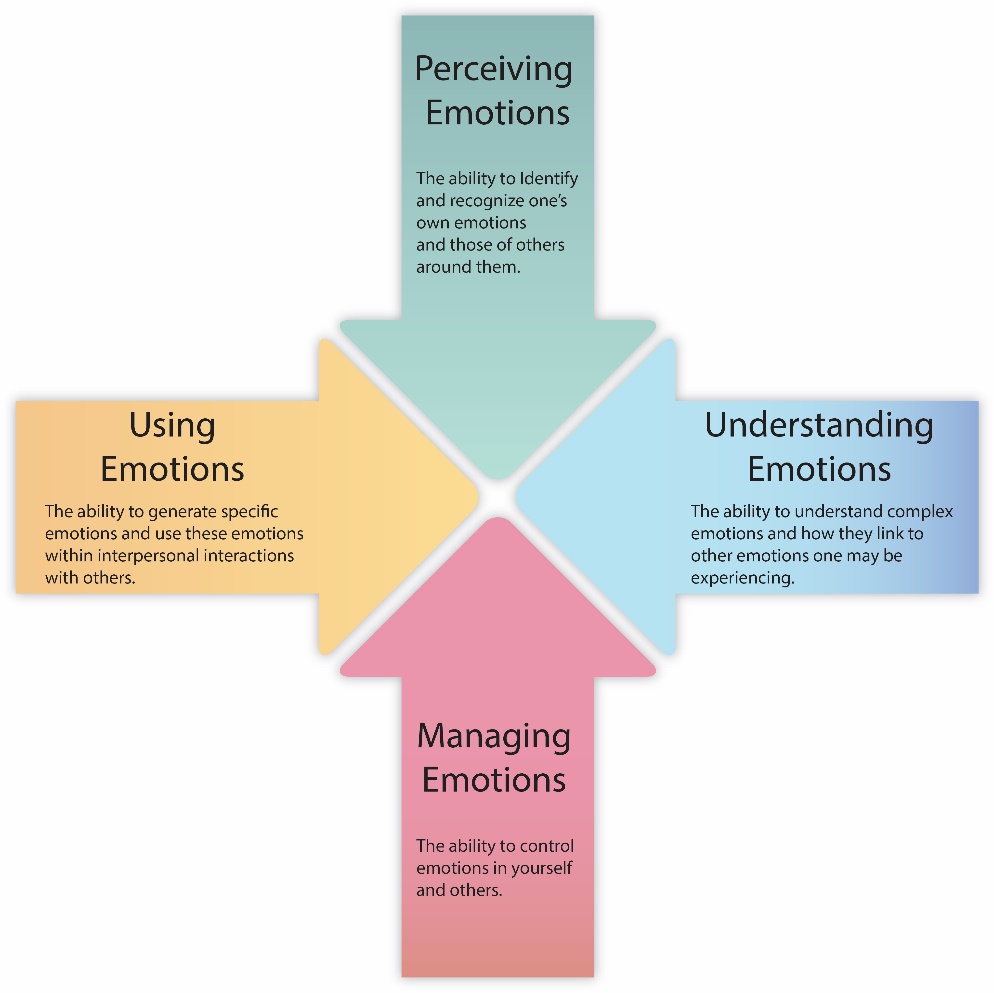

Emotional intelligence is an individual’s appraisal and expression of their emotions and the emotions of others in a manner that enhances thought, living, and communicative interactions. Emotional intelligence, while not a new concept, really became popular after Daniel Goleman’s book, Emotional Intelligence.55 Social psychologists had been interested in and studying the importance of emotions long before Goleman’s book, but his book seemed to shed new light on an old idea.56 Goleman drew quite a bit on a framework that was created by two social psychologists named Peter Salovey and John Mayer, who had coined the term “emotional intelligence” in an article in 1990.57 In the Salovey and Mayer framework for emotional intelligence, emotional intelligence consisted of four basic processes. Figure 3.8 pictorially demonstrates the four basic parts of Salovey and Mayer’s Emotional Intelligence Model.

Emotional intelligence (EQ) is important for interpersonal communication because individuals who are higher in EQ tend to be more sociable and less socially anxious. As a result of both sociability and lowered anxiety, high EQ individuals tend to be more socially skilled and have higher quality interpersonal relationships.

A closely related communication construct originally coined by Melanie and Steven Booth-Butterfield is affective orientation.58 As it is conceptualized by the Booth-Butterfields, affective orientation (AO) is “the degree to which people are aware of their emotions, perceive them as important, and actively consider their affective responses in making judgments and interacting with others.”59 Under the auspices of AO, the general assumption is that highly affective-oriented people are (1) cognitively aware of their own and others’ emotions, and (2) can implement emotional information in communication with others. Not surprisingly, the Booth-Butterfields found that highly affective-oriented individuals also reported greater affect intensity in their relationships.

Melanie and Steven Booth-Butterfield later furthered their understanding of AO by examining it in terms of how an individual’s emotions drive their decisions in life.60 As the Booth-Butterfields explain, in their further conceptualization of AO, they “are primarily interested in those individuals who not only sense and value their emotions but scrutinize and give them weight to direct behavior.”61 In this sense, the Booth-Butterfields are expanding our notion of AO by explaining that some individuals use their emotions as a guiding force for their behaviors and their lives. On the other end of the spectrum, you have individuals who use no emotional information in how they behave and guide their lives. Although relatively little research has examined AO, the conducted research indicates its importance in interpersonal relationships. For example, in one study, individuals who viewed their parents/guardians as having high AO levels reported more open communication with those parents/guardians.62

Personal-Social Dispositions

Social-personal dispositions refer to general patterns of mental processes that impact how people socially relate to others or view themselves. All of the following dispositions impact how people interact with others, but they do so from very different places. Without going into too much detail, we are going to examine the seven personal-social dispositions identified by John Daly.63

Loneliness

The first social-personal disposition is loneliness or an individual’s emotional distress that results from a feeling of solitude or isolation from social relationships. Loneliness can generally be discussed as existing in one of two forms: emotional and social. Emotional loneliness results when an individual feels that he or she does not have an emotional connection with others. We generally get these emotional connections through our associations with loved ones and close friends. If an individual is estranged from their family or doesn’t have close friendships, then he or she may feel loneliness as a result of a lack of these emotional relationships. Social loneliness, on the other hand, results from a lack of a satisfying social network. Imagine you’re someone who has historically been very social. Still, you move to a new city and find building new social relationships very difficult because the people in the new location are very cliquey. The inability to develop a new social network can lead someone to feelings of loneliness because he or she may feel a sense of social boredom or marginalization.

Loneliness tends to impact people in several different ways interpersonally. Some of the general research findings associated with loneliness have demonstrated that these people have lower self-esteem, are more socially passive, are more sensitive to rejection from others, and are often less socially skilled. Interestingly, lonely individuals tend to think of their interpersonal failures using an internal locus of control and their interpersonal successes externally.64

Depression

Depression is a psychological disorder characterized by varying degrees of disappointment, guilt, hopelessness, loneliness, sadness, and self-doubt, all of which negatively impact a person’s general mental and physical wellbeing. Depression (and all of its characteristics) is very difficult to encapsulate in a single definition. If you’ve ever experienced a major depressive episode, it’s a lot easier to understand what depression is compared to those who have never experienced one. Depressed people tend to be less satisfied with life and less satisfied with their interpersonal interactions as well. Research has shown that depression negatively impacts all forms of interpersonal relationships: dating, friends, families, work, etc. We will periodically come back to depression as we explore various parts of interpersonal communication.

Self-Esteem

As discussed earlier in this chapter, self-esteem consists of your sense of self-worth and the level of satisfaction you have with yourself; it is how you feel about yourself. A good self-image raises your self-esteem; a poor self-image often results in poor self-esteem, lack of confidence, and insecurity. Not surprisingly, individuals with low self-esteem tend to have more problematic interpersonal relationships.

Narcissism

Ovid’s story of Narcissus and Echo has been passed down through the ages. The story starts with a Mountain Nymph named Echo who falls in love with a human named Narcissus. When Echo reveals herself to Narcissus, he rejects her. In true Roman fashion, this slight could not be left unpunished. Echo eventually leads Narcissus to a pool of water where he quickly falls in love with his reflection. He ultimately dies, staring at himself, because he realizes that his love will never be met.

The modern conceptualization of narcissism is based on Ovid’s story of Narcissus. Today researchers view narcissism as a psychological condition (or personality disorder) in which a person has a preoccupation with one’s self, an inflated sense of one’s importance, and longing of admiration from others. Highly narcissistic individuals are completely self-focused and tend to ignore the communicative needs and emotions of others. In fact, in social situations, highly narcissistic individuals strive to be the center of attention.

Anita Vangelisti, Mark Knapp, and John Daly examined a purely communicative form of narcissism they deemed conversational narcissism.65 Conversational narcissism is an extreme focusing of one’s interests and desires during an interpersonal interaction while completely ignoring the interests and desires of another person: Vangelisti, Knapp, and Daly fond four general categories of conversationally narcissistic behavior. First, conversational narcissists inflate their self-importance while displaying an inflated self-image. Some behaviors include bragging, refusing to listen to criticism, praising one’s self, etc. Second, conversational narcissists exploit a conversation by attempting to focus the direction of the conversation on topics of interest to them. Some behaviors include talking so fast others cannot interject, shifting the topic to one’s self, interrupting others, etc. Third, conversational narcissists are exhibitionists, or they attempt to show-off or entertain others to turn the focus on themselves. Some behaviors include primping or preening, dressing to attract attention, being or laughing louder than others, positioning one’s self in the center, etc. Lastly, conversational narcissists tend to have impersonal relationships. During their interactions with others, conversational narcissists show a lack of caring about another person and a lack of interest in another person. Some common behaviors include “glazing over” while someone else is speaking, looking impatient while someone is speaking, looking around the room while someone is speaking, etc. As you can imagine, people engaged in interpersonal encounters with conversational narcissists are generally highly unsatisfied with those interactions.

Machiavellianism

In 1513, Nicolo Machiavelli (Figure 3.9) wrote a text called The Prince (http://www.gutenberg.org/files/1232/1232-h/1232-h.htm). Although Machiavelli dedicated the book to Lorenzo di Piero de’ Medici, who was a member of the ruling Florentine Medici family, the book was originally scribed for Lorenzo’s uncle. In The Prince, Nicolo Machiavelli unabashedly describes how he believes leaders should keep power. First, he notes that traditional leadership virtues like decency, honor, and trust should be discarded for a more calculating approach to leadership. Most specifically, Machiavelli believed that humans were easily manipulated, so ultimately, leaders can either be the ones influencing their followers or wait for someone else to wield that influence in a different direction.

In 1970, two social psychologists named Richard Christie and Florence Geis decided to see if Machiavelli’s ideas were still in practice in the 20th Century.66 The basic model that Christie and Geis proposed consisted of four basic Machiavellian characteristics:

- Lack of affect in interpersonal relationships (relationships are a means to an end);

- Lack of concern with conventional morality (people are tools to be used in the best way possible);

- Rational view of others not based on psychopathology (people who actively manipulate others must be logical and rational); and

- Focused on short-term tasks rather than long-range ramifications of behavior (these individuals have little ideological/organizational commitment).

Imagine working with one of these people. Imagine being led by one of these people. Part of their research consisted of creating a research questionnaire to measure one’s tendency towards Machiavellianism. The questionnaire has undergone several revisions, but the most common one is called the Mach IV (http://personality-testing.info/tests/MACH-IV.php).

Interpersonally, highly Machiavellian people tend to see people as stepping stones to get what they want. If talking to someone in a particular manner makes that other people feel good about themself, the Machiavellian has no problem doing this if it helps the Machiavellian get what he or she wants. Ultimately, Machiavellian behavior is very problematic. In interpersonal interactions where the receiver of a Machiavellian’s attempt of manipulation is aware of the manipulation, the receiver tends to be highly unsatisfied with these communicative interactions. However, someone who is truly adept at the art of manipulation may be harder to recognize than most people realize.

Empathy

Empathy is the ability to recognize and mutually experience another person’s attitudes, emotions, experiences, and thoughts. Highly empathic individuals have the unique ability to connect with others interpersonally, because they can truly see how the other person is viewing life. Individuals who are unempathetic generally have a hard time taking or seeing another person’s perspective, so their interpersonal interactions tend to be more rigid and less emotionally driven. Generally speaking, people who have high levels of empathy tend to have more successful and rewarding interactions with others when compared to unempathetic individuals. Furthermore, people who are interacting with a highly empathetic person tend to find those interactions more satisfying than when interacting with someone who is unempathetic.

Self-Monitoring

The last of the personal-social dispositions is referred to as self-monitoring. In 1974 Mark Snyder developed his basic theory of self-monitoring, which proposes that individuals differ in the degree to which they can control their behaviors following the appropriate social rules and norms involved in interpersonal interaction.67 In this theory, Snyder proposes that there are some individuals adept at selecting appropriate behavior in light of the context of a situation, which he deems high self-monitors. High self-monitors want others to view them in a precise manner (impression management), so they enact communicative behaviors that ensure suitable or favorable public appearances. On the other hand, some people are merely unconcerned with how others view them and will act consistently across differing communicative contexts despite the changes in cultural rules and norms. Snyder called these people low self-monitors.

Interpersonally, high self-monitors tend to have more meaningful and satisfying interpersonal interactions with others. Conversely, individuals who are low self-monitors tend to have more problematic and less satisfying interpersonal relationships with others. In romantic relationships, high self-monitors tend to develop relational intimacy much faster than individuals who are low self-monitors. Furthermore, high self-monitors tend to build lots of interpersonal friendships with a broad range of people. Low-self-monitors may only have a small handful of friends, but these friendships tend to have more depth. Furthermore, high self-monitors are also more likely to take on leadership positions and get promoted in an organization when compared to their low self-monitoring counterparts. Overall, self-monitoring is an important dispositional characteristic that impacts interpersonal relationships.

Key Takeaways

- Personality and temperament have many overlapping characteristics, but the basis of them is fundamentally different. Personality is the product of one’s social environment and is generally developed later in one’s life. Temperament, on the other hand, is one’s innate genetic predisposition that causes an individual to behave, react, and think in a specific manner, and it can easily be seen in infants.

- In both the scientific literature and in pop culture, there are many personality/temperament schemes that involve four specific parts. Table 3.1, in this chapter, showed a range of different personality quizzes/measures/tests that break temperament down into these four generic categories.

- In this section, we examined a range of different cognitive dispositions or personal-social dispositions. The cognitive dispositions (general patterns of mental processes that impact how people respond and react to the world around them) discussed in this chapter were the locus of control, cognitive complexity, authoritarianism, dogmatism, emotional intelligence, and AO. The social-personal dispositions (general patterns of mental processes that impact how people socially relate to others or view themselves) discussed in this chapter were loneliness, depression, self-esteem, narcissism, Machiavellianism, empathy, and self-monitoring.

Exercises

- Complete the Keirsey Temperament Sorter®-II (KTS®-II; https://profile.keirsey.com/#/b2c/assessment/start). After finding out your temperament, reflect on what your temperament says about how you interact with people interpersonally.

- Watch the following animated video over-viewing Daniel Goldman’s book Emotional Intelligence (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=n6MRsGwyMuQ). After watching the video, what did you learn about emotional intelligence? How can you apply emotional intelligence in your own life?

- Complete the Self-Monitoring Scale created by Mark Snyder (http://personality-testing.info/tests/SM.php). After finishing the scale, what do your results say about your ability to adapt to changing interpersonal situations and contexts?

3.3 Communication & Relational Dispositions

Learning Objectives

- List and explain the different personality traits associated with Daly’s communication dispositions.

- List and explain the different personality traits associated with Daly’s relational dispositions.

In the previous section, we explored the importance of temperament, cognitive dispositions, and personal-social dispositions. In this section, we are going to explore the last two dispositions discussed by John Daly: communication and relational dispositions.68

Communication Dispositions

Now that we’ve examined cognitive and personal-social dispositions, we can move on and explore some intrapersonal dispositions studied specifically by communication scholars. Communication dispositions are general patterns of communicative behavior. We are going to explore the nature of introversion/extraversion, approach and avoidance traits, argumentativeness/verbal aggressiveness, and lastly, sociocommunicative orientation.

Introversion/Extraversion

The concept of introversion/extraversion is one that has been widely studied by both psychologists and communication researchers. The idea is that people exist on a continuum that exists from highly extraverted (an individual’s likelihood to be talkative, dynamic, and outgoing) to highly introverted (an individual’s likelihood to be quiet, shy, and more reserved). Before continuing, take a second and fill out the Introversion Scale created by James C. McCroskey and available on his website (http://www.jamescmccroskey.com/measures/introversion.htm). There is a considerable amount of research that has found an individual’s tendency toward extraversion or introversion is biologically based.69 As such, where you score on the Introversion Scale may largely be a factor of your genetic makeup and not something you can alter greatly.

When it comes to interpersonal relationships, individuals who score highly on extraversion tended to be perceived by others as intelligent, friendly, and attractive. As such, extraverts tend to have more opportunities for interpersonal communication; it’s not surprising that they tend to have better communicative skills when compared to their more introverted counterparts.

Approach and Avoidance Traits

The second set of communication dispositions are categorized as approach and avoidance traits. According to Virginia Richmond, Jason Wrench, and James McCroskey, approach and avoidance traits depict the tendency an individual has to either willingly approach or avoid situations where he or she will have to communicate with others.70 To help us understand the approach and avoidance traits, we’ll examine three specific traits commonly discussed by communication scholars: shyness, communication apprehension, and willingness to communicate.

Shyness

In a classic study conducted by Philip Zimbardo, he asked two questions to over 5,000 participants: Do you presently consider yourself to be a shy person? If “No,” was there ever a period in your life during which you considered yourself to be a shy person?71 The results of these two questions were quite surprising. Over 40% said that they considered themselves to be currently shy. Over 80% said that they had been shy at one point in their lifetimes. Another, more revealing measure of shyness, was created by James C. McCroskey and Virginia Richmond and is available on his website (http://www.jamescmccroskey.com/measures/shyness.htm).72 Before going further in this chapter, take a minute and complete the shyness scale.