Chapter 18: Exchange Rate and Trade Finance

18.3 Exchange Rate Systems

Foreign exchange market plays a very important role in international trade and affects the trade finance decisions of importers and exporters. The demand for and supply of any currency and exchange rate changes help traders in deciding their payment terms. In practice, exchange rates depend on the type of exchange rate systems that countries adopt.

The International Monetary Fund (IMF), created to monitor and assist countries with international payments problems, maintains a list of currency regimes used by different countries. The list displays a wide variety of systems currently being used. The continuing existence of so much variety demonstrates that the key question, “Which is the most suitable currency system?” remains largely unanswered.

As per the International Monetary Fund,

Of the 30 countries whose exchange rate arrangement was reclassified as of April 2021, 14 countries (47 percent) were reclassified to a more flexible arrangement (compared with 7 of 15 countries, or 47 percent, during the previous reporting period); 16 countries (53 percent) were classified to a more managed arrangement (compared with 8 of 15 countries, or 53 percent, during the previous reporting period) (International Monetary Fund, 2022, p. 5).

Let's Explore

One of the decisions a country must make with respect to its currency is whether to fix its exchange value and try to maintain it for an extended period, or to allow its value to float or fluctuate according to market conditions. Broadly, we can distinguish three types of exchange rate regimes: a free-float, a managed-float, and a fixed exchange rate.

Let’s consider these exchange rate systems in more detail.

Free-Floating System

In a free-floating exchange rate system, governments and central banks do not intervene in the market for foreign exchange in order to influence the exchange rate. The relationship between governments and central banks on the one hand and currency markets on the other is much the same as the typical relationship between these institutions and stock markets. Governments may regulate stock markets to prevent fraud, but stock values themselves are left to float in the market. The U.S. government, for example, does not intervene in the stock market to influence stock prices.

The concept of a completely free-floating exchange rate system is a theoretical one. In practice, all governments or central banks intervene in currency markets in an effort to influence exchange rates. Some countries, such as the United States, intervene to only a small degree, so that the notion of a free-floating exchange rate system comes close to the exchange rate system that actually exists in the United States.

Managed Float System

Governments and central banks often seek to increase or decrease their exchange rates by buying or selling their own currencies in the foreign exchange market. The purpose of such intervention is to prevent sudden large swings in the value of a nation’s currency. Exchange rates are still free to float, but government purchases and sales influence their values. When governments or central banks intervene in the foreign exchange market in this way in a floating exchange rate system, what results is a managed float.

A 2022 Bank of International Settlements survey found that $7.5 trillion per day is traded on foreign exchange markets, which makes the foreign exchange market the largest market in the world economy (Bank of International Settlements, 2022).[1] In such a case, it is difficult for any one agency—even an agency the size of the U.S. government —to force significant changes in exchange rates.

Fixed Exchange Rates

In a fixed exchange rate regime, the government intervenes actively through the central bank to maintain convertibility of their currency into other currencies at a fixed exchange rate. The central bank sets an official exchange rate and intervenes in the foreign exchange market to offset the effects of fluctuations in supply and demand and maintain a constant exchange rate. For instance, In Canada the exchange rate was fixed by policy in 1960s at USD1 = CAD1.075 CAD (CAD1 was approximately USD0.925) and the Bank of Canada intervened in the foreign exchange market to maintain that rate (Curtis & Irvin, n.d.). There are several mechanisms through which fixed exchange rates may be maintained. Whatever is the system for maintaining these rates, all fixed exchange rate systems share some important features:

- A Commodity Standard: In a commodity standard system, countries fix the value of their respective currencies relative to a certain commodity or group of commodities. With each currency’s value fixed in terms of the commodity, currencies are fixed relative to one another.

- Fixed Exchange Rates through Intervention: The Bretton Woods Agreement called for each currency’s value to be fixed relative to other currencies. The mechanism for maintaining these rates, however, was to be intervention by governments and central banks in the currency market.

Did You Know? How Countries Choose Between Fixed and Floating Exchange Rates

Obviously, there is not one answer for all countries, or we would not see different exchange rate regimes today. With flexible rates, the foreign exchange market sets the exchange rate, and monetary policy is available to pursue other targets. On the other hand, fixed exchange rates require central bank intervention. Monetary policy is aimed at the exchange rate.The importance a country attaches to an independent monetary policy is one very important factor in the choice of an exchange rate regime. Another is the size and volatility of the international trade sector of the economy. A flexible exchange rate provides some automatic adjustment and stabilization in times of change in net exports or net capital flows.

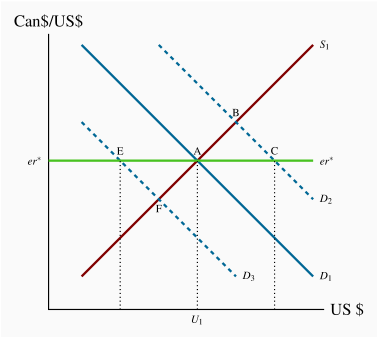

Let’s try to understand the concept of exchange rate regime by using Figure 18.2. In this figure, suppose the exchange rate is fixed at [latex]\textit{er*}[/latex]. There would be a free market equilibrium at [latex]\text{A}[/latex] if the supply curve for U.S. dollars is [latex]\textit{S}_{1}[/latex] and the demand curve for U.S. dollars is [latex]\textit{D}_{1}[/latex]. The central bank does not need to buy or sell U.S. dollars. The market is in equilibrium and clears by itself at the fixed rate.

Credit: "Figure 12.4 Central bank intervention to fix the exchange rate" by D. Curtis and I. Irvine, CC BY-NC-SA.

Suppose demand for U.S. dollars shifts from [latex]\textit{D}_{1}[/latex] to [latex]\textit{D}_{2}[/latex]. Canadians want to spend more time in Florida to escape the long, cold Canadian winter. They need more U.S. dollars to finance their expenditures in the United States. The free-market equilibrium would be at B, and the exchange rate would rise if the Bank of Canada takes no action.However, with the exchange rate fixed by policy at [latex]\textit{S}_{1}[/latex][latex]\textit{er*}[/latex] there is an excess demand for U.S. dollars equal to AC. To peg, or set, the exchange rate, the Bank of Canada sells U.S. dollars from the official exchange reserves in the amount [latex]\text{AC}[/latex].The supply of U.S. dollars on the market is then the "market" supply represented by [latex]\textit{S}_{1}[/latex] plus the amount [latex]\text{AC}[/latex] supplied by the Bank of Canada. The payment the Bank receives in Canadian dollars is the amount ([latex]\textit{er*}\times\text{AC}[/latex]), which reduces the monetary base by that amount. The lower monetary base pushes domestic interest rates up and attracts a larger net capital inflow. Higher interest rates also reduce domestic expenditure and the demand for imports and for foreign exchange. The exchange rate target drives the Bank's monetary policy, which in turn changes both international capital flows and domestic income and expenditure.

What if the demand for U.S. dollars falls to [latex]\textit{D}_{3}[/latex]? The market equilibrium would be at [latex]\text{F}[/latex]. At the exchange rate at [latex]\textit{er*}[/latex] there is an excess supply of U.S. dollars [latex]\text{EA}[/latex]. To defend the currency peg, the Bank of Canada would have to buy [latex]\text{EA}[/latex] U.S. dollars, reducing the supply of U.S. dollars on the market to meet the “unofficial” demand. The Bank of Canada would have to buy [latex]\text{EA}[/latex] U.S. dollars, reducing the supply of U.S. dollars on the market to meet the “unofficial” demand. The Bank of Canada's purchase would be added to foreign exchange reserves. The Bank would pay for these U.S. dollars by creating more monetary base, as in the case of an open market purchase of government securities.

In either case, maintaining a fixed exchange rate requires central bank intervention in the foreign currency market. The central bank's monetary policy is expansionary because it is committed to the exchange rate target. When the demand schedule is [latex]\textit{D}_{2}[/latex], foreign exchange reserves are running down. When the demand schedule is [latex]\textit{D}_{3}[/latex], foreign exchange reserves are increasing. If the demand for U.S. dollars fluctuates between [latex]\textit{D}_{2}[/latex] and [latex]\textit{D}_{3}[/latex], the Bank of Canada can sustain and stabilize the exchange rate in the long run.

However, if the demand for U.S. dollars is, on average, [latex]\textit{D}_{2}[/latex], the foreign exchange reserves are steadily declining to support the exchange rate [latex]\textit{er*}[/latex], and the monetary base is falling as well. In this case, the Canadian dollar is overvalued at [latex]\textit{er*}[/latex]; or, in other words, [latex]\textit{er*}[/latex] is too low a price for the U.S. dollar. A higher [latex]\textit{er}[/latex] is required for long-run equilibrium in the foreign exchange market and the balance of payments. As reserves start to run out, the government may try to borrow foreign exchange reserves from other countries and the International Monetary Fund (IMF), an international body that exists primarily to lend to countries in short-term difficulties.

At best, this is only a temporary solution. Unless the demand for U.S. dollars decreases, or the supply increases in the longer term, it is necessary to devalue the Canadian dollar. If a fixed exchange rate is to be maintained, the official rate must be reset at a higher domestic currency price for foreign currency.

Real Cases

For many years frequent media and political discussions of the persistent rise in China's foreign exchange holdings provide a good example of the defense of an undervalued currency. With the yuan at its current fixed rate relative to U.S. dollars and other currencies, China has a large current account surplus that is not offset by a financial account deficit. Balance of payments equilibrium requires ongoing intervention by the Chinese central bank to buy foreign exchange and add to official reserve holdings. Buying foreign exchange adds to the monetary base and money supply, raising concerns about inflation. The Bank has responded in part with a small revaluation of the yuan and in part with an increase in the reserve requirements for Chinese banks. Neither of these adjustments has been sufficient to change the situation fundamentally and growth in official foreign exchange reserves continues.

In Europe, the euro currency system effectively fixes exchange rates among member countries. Individual member countries do not have national monetary policies. Monetary policy is set by the European Central Bank. In the years following the “Great Recession,” this has been a source of controversy because economic and fiscal conditions have differed significantly among countries. Countries trying to adjust fiscal deficits and national public debt crises have been forced into fiscal austerity without offsetting monetary policy support. In many cases the results have been deep and prolonged recessions without solving their debt problems. Greece is the poster child.

Of course, it is not necessary to adopt the extreme regimes of pure or clean floating on the one hand and perfectly fixed exchange rates on the other hand. Dirty or managed floating is used to offset large and rapid shifts in supply or demand schedules in the short run. The intent is to smooth the adjustment as the exchange rate is gradually allowed to find its equilibrium level in response to longer-term changes.

Source: Adapted from 12.3: Flexible exchange rates and fixed exchange rates in Principles of Macroeconomics by D. Curtis & I. Irvine, licensed under CC BY-NC-SA.

References

Bank for International Settlements. (2022). Triennial Central Bank Survey: OTC foreign exchange turnover in April 2022 [PDF]. https://www.bis.org/statistics/rpfx22_fx.pdf

Curtis, D. & Irvine, I. (n.d.). Principles of Macroeconomics. LibreTexts Libraries. https://socialsci.libretexts.org/Bookshelves/Economics/Principles_of_Macroeconomics_(Curtis_and_Irvine)

International Monetary Fund. (2022). Annual report on exchange arrangements and exchange restrictions 2021. Monetary and Capital Markets Department. https://doi.org/10.5089/9781513598956.012

Attributions

“18.3 Exchange Rate Systems” is adapted from “30.3 Exchange Rate Systems” from Principles of Economics v. 2.0 by Saylor Academy and is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 International License, except where otherwise noted.

“Did You Know? How Countries Choose Between Fixed and Floating Exchange Rates” is adapted from "12.3: Flexible exchange rates and fixed exchange rates" in Principles of Macroeconomics by D. Curtis and I. Irvine, licensed under a CC BY-NC-SA , except where otherwise noted.

"Figure 18.2: Central bank intervention to fix the exchange rate" is reused from "Figure 12.4 Central bank intervention to fix the exchange rate" in 12.3: Flexible exchange rates and fixed exchange rates" in Principles of Macroeconomics by D. Curtis and I. Irvine, licensed under a CC BY-NC-SA , except where otherwise noted.

Image Descriptions

Figure 18.2: Central Bank Intervention to Fix the Exchange Rate

This image is a graph depicting the exchange rate between Canadian dollars and U.S. dollars. The vertical axis is labelled “Can$/US$” and the horizontal axis is labelled “US $.” The graph contains several lines intersecting at various points:

- A green horizontal line at the center labelled "er*" extends across the graph from left to right.

- Three blue lines starting from the top-left, moving down towards the bottom-right; in the middle is a solid line labelled "D1", at right is a dotted line labelled "D2", and at left is a dotted line labelled "D3" (dotted), representing different demand curves.

- A solid red line starting from the bottom-left and moving up towards the top-right is labelled "S1".

- The blue demand lines intersect the red line at F, A and B and the green horizontal line at E, A, and C.

- There are also three vertical dashed lines from points E, A, and C down to the horizontal axis. The centre line is labelled "U1".

[back]

- In Chapter 18, all $ refer to USD unless otherwise noted. ↵

the policy choice that determines how foreign exchange markets operate

a national currency that can be freely exchanged for a different national currency at the prevailing exchange rate

an exchange rate set by government policy that does not change as a result of changes in market conditions

foreign currency held by a government and managed by the central bank

a policy in which a national government or central bank sets a fixed exchange rate for its currency with a foreign currency or a basket of currencies and stabilizes the exchange rate between countries

purchases or sales of foreign currency intended to manage the exchange rate

a reduction (increase) in the international value of the domestic currency