Chapter 8: Economic Integration, International Resource Movement, and Multinational Enterprises

8.4 The Effects of International Migration

In our discussions up to this point we have assumed that factors of production, while mobile in domestic markets, do not move internationally. We are now going to examine the international movement of factors of production, beginning with the movement of labour – international migration.

International migration is the movement of people from one country to another in which they plan to live for a relatively long period of time. While international migration has contributed significantly to economic activity in receiving countries, it remains a contentious issue, particularly in the developed world.

In what follows, we will analyze the economic effects of international migration on both sending and receiving countries and then check how our main conclusions compare against actual experience. We presume that international migration is motivated by economic considerations – in everyday language – by a search for better economic opportunity. Assuming that people leave countries where wages are low to go to countries where wages are high, our main conclusions are that receiving countries benefit from the additional supplies of labour while sending countries lose. However, within the two sets of countries, the gains and losses are distributed unevenly. For the world as a whole, international migration brings benefits.

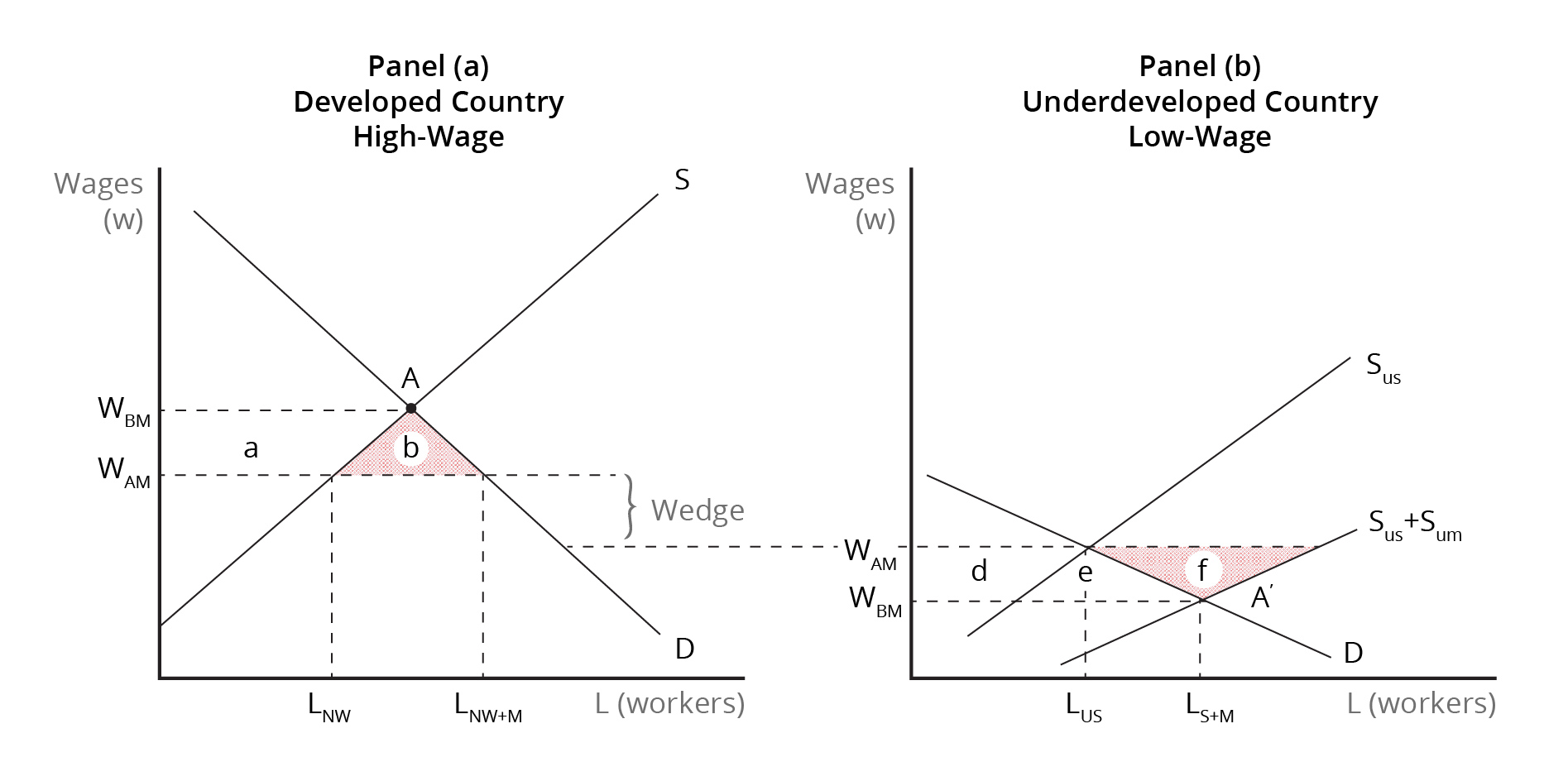

We analyze the economic effects of international migration on the labour market with the help of Figure 8.2. We assume two separate labour markets – one in the sending country and the other in the receiving country. The wage rate is low in the sending country and high in the receiving country. This sets the motivation for international migration – workers in the low-wage country would be interested in moving to the high-wage country to do better economically. In our analysis, we assume that the high-wage country is a developed (rich) country, and the low-wage country is an underdeveloped (poor) country.

Credit: © by Kenrick H. Jordan and Conestoga College, CC BY-NC-SA 4.0.

The labour market in the developed country is illustrated in Panel (a) in Figure 8.2 using a typical supply and demand diagram. The supply of labour is indicated by [latex]\text{S}_{D}[/latex], and the demand for labour is given by [latex]\text{D}_{D}[/latex]. The intersection of the supply and demand curves gives a high wage rate in equilibrium ([latex]\text{W}_{D}\text{*}[/latex]) at point [latex]\text{A}[/latex]. The labour market in the underdeveloped country is shown in Panel (b) in Figure 8.2 using a similar supply and demand diagram. However, in the case of an underdeveloped country, the supply of labour is segmented to distinguish the workers who are left after migration has taken place. The workers who stay [latex](\text{S}_{US})[/latex] plus the workers who migrate [latex](\text{S}_{UM})[/latex] make up the total supply of labour [latex](\text{S}_{US}+\text{S}_{UM})[/latex]. The intersection of the total labour supply and the demand curve in the underdeveloped country gives a low wage rate in equilibrium [latex](\text{W}_{U}\text{*})[/latex] at point [latex]\text{A}^\prime[/latex].

Suppose now that the free cross-border movement of labour is allowed to take place. As workers migrate from the underdeveloped country, its wage rate begins to rise. As migrants are added to the workforce in the developed country, its wage rate begins to fall. While there is a tendency for the wage rates in the two countries to equalize, this ultimately will not occur because the transaction costs and risks associated with migration are significant. These factors, therefore, act as a wedge which keeps wage rates in the developed and underdeveloped countries separate.

After migration stops, the workers remaining in the underdeveloped country receive a higher wage, [latex]\text{W}_{AM}[/latex]. As a result, there is a fall in the quantity of labour employed from [latex]\text{L}_{S+M}[/latex] to [latex]\text{L}_{S}[/latex]. These workers, therefore, gain economic surplus equal to area [latex]\textit{d}[/latex]. Meanwhile, employers in this country are worse off, as they are hiring less labour and paying a higher wage. They lose economic surplus equal to the sum of areas [latex]\textit{d}[/latex] and [latex]\textit{e}[/latex]. Some of what employers in this country lose, area [latex]\textit{d}[/latex], is a transfer of surplus to the workers remaining after migration. Since employers lose more than the remaining workers gain, the underdeveloped country definitely loses economic well-being. Its net loss is indicated by area [latex]\textit{e}[/latex].

Employers in the developed country experience a gain in economic surplus because they are able to hire more labour at a lower wage rate due to the additional labour supply. Referring to Figure 8.2, they gain the sum of areas [latex]\textit{a}+{b}[/latex]. Meanwhile, native workers – those in the country prior to immigration – see their wage decline and supply a smaller quantity of labour at [latex]\text{L}_{D}[/latex]. As a result, they lose economic surplus equal to area a. What workers in this country lose, area [latex]\textit{a}[/latex], represents a transfer to employers. Since employers gain more than native workers lose, the developed country receives a net gain in economic well-being indicated by area [latex]\textit{b}[/latex]. The receiving country – the developed country – is definitively better off with immigration.

The world benefits from immigration as labour resources are allocated more efficiently. Labour moves from the country in which it has a relatively low value to the one where its value it has a higher value. Since wage rates reflect labour productivity, the real location of labour resources implies an increase in global output. The is measured by the gain in economic surplus accruing to the migrants, the sum of areas [latex]\textit{e}[/latex] and [latex]\textit{f}[/latex] in Panel (b) of Figure 8.2. Part of what the migrant workers gain, area [latex]\textit{e}[/latex], is loss to employers in the underdeveloped country. The world as gains the sum of areas [latex]\textit{b}+{f}[/latex].

Empirical studies have shown that the historical experience with migration bears out the conclusions of the above analysis. Immigration tends to reduce the disparity in wages between countries. Workers in receiving countries who are in direct competition with migrants usually experience a decline in their wages relative to other occupations. The earnings of immigrants tend to rise relative to those of native workers over time, but the gap usually does not close during their lifetimes. Last, world output rises as a result of migration.

Let’s Explore: Economics of Migration

Learn more about how the migration of people has an affect on modern national economies by watching this video.

Source: CNBC International. (2018, December 22). How does immigration impact the economy? | CNBC Explains [Video]. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=f0dVfDiSrFo

Image Descriptions

Figure 8.2: The Economic Effects of Migration.

The image shows two economic graphs side by side labelled Panel (a) Developed Country High Wage and Panel (b) Underdeveloped Country Low-Wage. Both graphs have an x-axis labelled "L (workers)" and a y-axis marked "Wages (w)."

Panel (a), on the left, has two intersecting lines labelled 'S' and 'D.’ The equilibrium point is denoted by 'A' at the centre. The y-axis is marked with WBM and WAM, with dotted horizontal lines extending across, and the x-axis is marked with LNW and LNW+M and dotted horizontal lines running up to the WAM line. The area to the left and above the Supply curve between the WBM and WAM dotted lines is labelled a. The triangle formed by WAM below A and between Supply and Demand is shaded and labelled b. WAM extends beyond the Demand curve to the right, and lower down the Demand curve, an additional horizontal dotted line extends to the right. The space between these extended dotted lines is labelled Wedge.

Panel (b), on the right, has a demand curve beginning lower down the y-axis. Two diagonal supply curves rise partway up the graph, labelled SUS and SUS+SUM. The intersection of SUS+SUM and Demand is labelled A prime. The y-axis is marked with WAM with a horizontal dotted line through where D and SUS intersect, which ends at SUS+SUM. Lower on the y-axis is WBM with a horizontal dotted line through SUS extending to the intersection of Demand and SUS+SUM. Where the W lines intersect with Demand, vertical horizontal lines go to the x-axis at LUS and LS+M. Area d is closest to the y-axis, in the space created by WAM, WBM and SUS. Area e is the space below the intersection of Demand and SUS and above WBM. Area f is shaded, next to e, and created by demand, WAM and SUS+SUM.

[back]

the movement of people from one country to another country where they plan to live for a relatively long period of time

the country that people leave in order to reside in another country (in the context of a multinational enterprise)

the country to which people move and plan to reside for a relatively long period of time (in the context of a multinational enterprise)