Chapter 8: Economic Integration, International Resource Movement, and Multinational Enterprises

8.2 The Theory of Economic Integration

In this section, we discuss the economic effects of economic integration through trading blocs. Starting with a common level of protection against imports from all other sources, we examine the effects, in terms of gains or losses, of removing barriers to trade among certain countries. Whether a preferential trade arrangement raises the economic well-being of a country depends on the extent to which the trading arrangement causes trade diversion versus trade creation (Saylor Academy, n.d.). The removal of trade barriers among participating countries facilitates an expansion of trade. However, trade is shifted away from lower-cost production to which the common level of import protection applies to higher-cost production from within the trading bloc. Overall, the static effects of participation in a regional trading bloc depend on whether the benefits of trade creation exceed the costs of trade diversion. We will consider this static view first and then consider some dynamic effects that can arise from economic integration arrangements.

Static Effects – Trade Creation and Trade Diversion

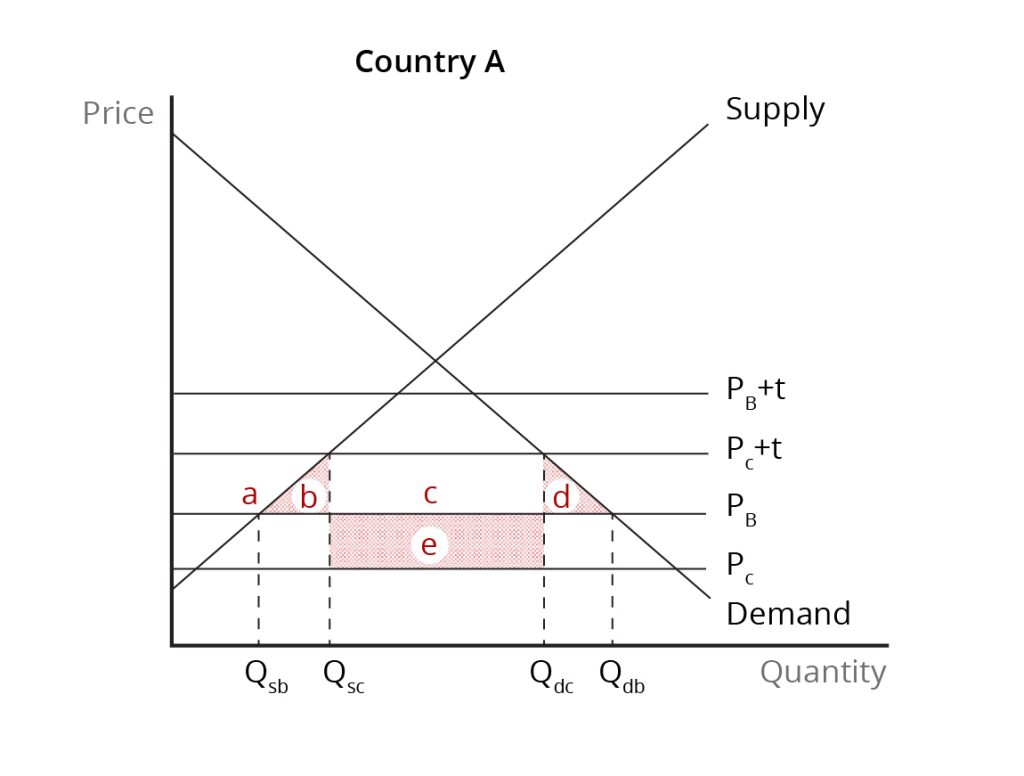

We illustrate the static effects of trade creation and trade diversion in Figure 8.1. We assume that we are in a world made up of just three countries – Country A, Country B, and Country C. Two of these countries – Country A and Country B – agree to form a customs union, which involves free trade in goods and services among them and a common tariff against imports from Country C. As a result of the formation of the customs union, tariffs that previously existed on trade between Countries A and B are removed although similar tariffs on Country C remain. This highlights the discriminatory impact of the customs union – trade between Countries A and B is favoured compared to trade with Country C.

Credit: © by Kenrick H. Jordan and Conestoga College, CC BY-NC-SA 4.0.

We assume that Country A is a small importer in that it is unable to influence the price of the imported product. The price and supply curves for the alternative producers, Country B and Country C, are therefore represented by horizontal lines in the supply and demand diagram that used to depict the domestic market of Country A. Country B is a relatively high-cost producer of the good under consideration while Country C is the producer with the lowest cost among the three countries.

Prior to the formation of the customs union, both Country B and Country C faced the same import tariff which raised the price to consumers from these two sources in Country A’s domestic market. Thus, the domestic price of the product from Country B is given by [latex]\text{P}_{b}+{t}[/latex], where [latex](\textit{t})[/latex] represents the tariff, and the domestic price of the product from Country C is [latex]\text{P}_{c}+{t}[/latex]. At the lower price of [latex]\text{P}_{c}+{t}[/latex], producers in Country A supply [latex]\text{Q}_{sc}[/latex] while consumers purchase [latex]\text{Q}_{dc}[/latex], with the difference between these two quantities being imports.

With the formation of the customs union, the tariff is removed on imports from Country B but remains in place for imports from Country C. This means that the price of imports from Country B falls below that of Country C in the domestic market. As a result, the quantity produced in Country A falls to [latex]\text{Q}_{sb}[/latex], as only the more efficient domestic producers can supply the product. Meanwhile, the quantity purchased rises to [latex]\text{Q}_{db}[/latex]. The quantity of imports, therefore, increases. There is clearly an increase in trade as a result of the customs union. This trade creation results because higher-cost production of a member of the customs union (Country A) is replaced by lower cost imports from another member (Country B). This represents an increase in well-being for Country A because consumer surplus rises and there has been an efficiency gain in production. Trade creation is the sum of the production effect (area [latex]\textit{b}[/latex]) and the consumption effect (area [latex]\textit{d}[/latex]).

However, the customs union can have an adverse effect on well-being to the extent that it diverts trade from low-cost production. Before the formation of the customs union, Country A bought all its imports from Country C, the low-cost producer. After the formation of the customs union, all imports came from Country B. Trade was therefore diverted from Country C to Country B. Country A is therefore choosing to substitute in consumption higher-cost supplies for lower-cost supplies. This has a negative impact on economic well-being as it represents an inefficient allocation of resources from a global standpoint. The increase in the cost of obtaining the increase in imports is given by area e in Figure 8.1.

Whether the formation of the customs union leads to an improvement in economic well-being depends on whether the positive trade creation effect outweighs the negative trade diversion effect; that is, if the sum of area [latex]\textit{b}+{d}[/latex] is greater than area [latex]\textit{e}[/latex]. There are two factors that increase the likelihood that there will be a net gain in economic well-being from a customs union. First, the lower the production costs of the partner’s country relative to the most efficient producer, the greater the net gains, because any trade diversion will be less costly. Second, the greater the responsiveness of import demand to a change in price, the greater the net gain as trade creation in response to any decline in the domestic price will be larger.

Dynamic Effects

Some effects of regional trading blocs are dynamic, meaning that they occur over time. These effects arise because the formation of a trading bloc increases the size of a market. Dynamic benefits are likely to outweigh the negative effects of trade diversion and include economies of scale, heightened competition, and greater opportunities for investment.

With the formation of a regional trading bloc, trade barriers in smaller individual markets are removed. This allows producers within the bloc to exploit economies of scale that were formerly unavailable. The increase in market size may facilitate exploitation of comparative advantage, allowing producers to specialize in specific lines of production. The larger market is also likely to encourage increased competition as the number of product versions within the trading bloc is now larger. In order to remain viable in the face of stiffer competition, producers must become more productive, which allows them to reduce costs and cut prices. The movement towards freer trade within the trading bloc also pushes producers to innovate, paving the way for increased investment in research and development, new technologies, and better machinery and equipment.

In summary, we highlight the following major sources of benefit from the formation of trading:

- A reduction in prices and production costs due to economies of scale, increased competition, and innovation;

- Greater product diversity as the number of versions of a product rises; and

- Increased opportunity for investment due to larger market size, greater competition, and the need for innovation.

References

Saylor Academy. (n.d.). International economics: Theory and policy, (v.1) [PDF]. The Saylor Foundation. https://resources.saylor.org/wwwresources/archived/site/textbooks/International%20Economics%20-%20Theory%20and%20Policy.pdf

Image Descriptions

Figure 8.1: The Static Effects of a Customs Union

This image is a graph labelled “Country A” with supply and demand curves with “Price” on the vertical axis and “Quantity” on the horizontal axis. The supply curve is upward-sloping, and the demand curve is downward-sloping, intersecting each other, creating an x-shaped formation. The equilibrium is disrupted by four horizontal price lines, with tariffs labelled PB + t and Pc + t and without tariffs, PB and Pc. Along the PB line, areas are labelled with lowercase letters ‘a’ through ‘e.’ Area a is closest to the vertical axis, above the supply line, with a horizontal dotted line to the x-axis labelled Qsb. Area b is a shaded triangle formed by the supply line, line PB, and a dotted horizontal line from PB+t to the x-axis labelled Qsc. Area c is the rectangular space from the dotted Qsc, above line PB and below Pc + T, ending with a horizontal dotted line from the demand line intersection with Pc +T down to the x-axis and labelled Qdc. Area d is shaded and mirrors area b, formed by the demand line, PB and Qdc. Area e mirrors area c, but below line PB.

[back]