Chapter 6: Trade Restrictions: Arguments for Protection and the Cost of Protection

6.4 The Case of the Infant Industry

The infant industry argument for protection from import competition has existed for a long time, having first been advocated by Alexander Hamilton in 1792 in the United States. The essential idea is that government can support emerging industries with temporary import tariffs until they are sufficiently strong to produce at comparatively low cost. Eventually, such domestic industries will be able to hold their own in international markets without tariff protection. One important respect in which this argument for protection differs from others is that it is a dynamic rather than a static one. The expectation is that the efficiency of the industry will improve over time. The GATT/WTO recognizes the infant-industry argument as a legitimate reason for protection.

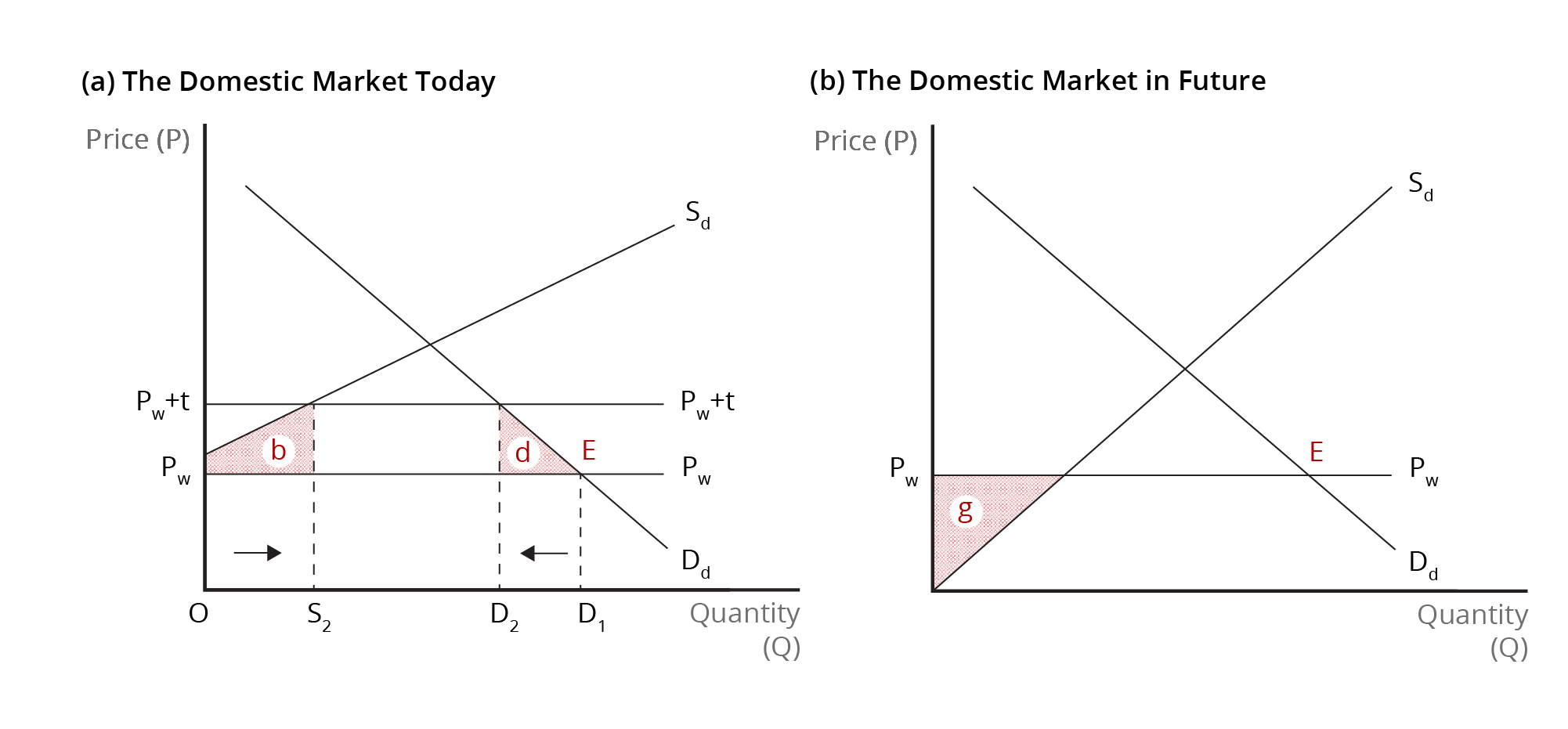

We demonstrate the infant-industry case for protection in a small country in Figure 6.4. The domestic market, where [latex]\text{D}_{d}[/latex] represents the domestic demand curve and [latex]\text{S}_{d}[/latex] represents the domestic supply curve, yields a relatively high price for the product at the intersection of the two curves. Since the country is small, it is able to purchase any quantity of the product at the lower world price, [latex]\text{P}_{w}[/latex]. Initially, we assume that domestic production in our small country is not at all competitive with foreign production, which means that the domestic supply curve lies above the world price line, [latex]\text{P}_{w}[/latex], throughout its entire range. At the initial equilibrium with free trade (point [latex]\text{E}[/latex]), the amount of the product purchased by domestic consumers is indicated by [latex]\text{D}_{1}[/latex] – all domestic purchases are satisfied by imports and domestic production is not viable.

Credit: © by Kenrick H. Jordan and Conestoga College, CC BY-NC-SA 4.0.

In order to encourage domestic production, the government imposes an import tariff, which raises the domestic price to [latex]\text{P}_{w}+\textit{t}[/latex], where [latex]\textit{t}[/latex] is the tariff. As a result of the higher domestic price, producers supply the quantity of the product indicated by [latex]\text{S}_{2}[/latex] and consumers reduce the quantity they purchase from [latex]\text{D}_{1}[/latex] to [latex]\text{D}_{2}[/latex]. Thus, the quantity of imports falls from [latex]\text{D}_{1}[/latex] to [latex]\text{D}_{1}-\text{S}_{2}[/latex] to [latex]\text{D}_{2}-\text{S}_{2}[/latex]. With the import tariff allowing domestic production to begin, the usual deadweight losses due to the production effect and the consumption effect are incurred. Initially, therefore, the small country would experience the usual net national loss in economic well-being from tariff protection. This situation is depicted in Figure 6.4 (a).

However, as domestic production continues over time, domestic producers gain experience and are able to find ways to lower their production costs. This means that the domestic supply curve, [latex]\text{S}_{d}[/latex], begins to shift downward over time. The downward shift of the domestic supply curve facilitates the creation of producer surplus that would not exist in the absence of the tariff. Once the domestic industry becomes internationally competitive, the import tariff can be removed. This situation is depicted if Figure 6.4 (b), where the domestic supply curve is lower, the tariff is removed, the domestic price is once more equal to the world price, and producer surplus equal to area [latex]\textit{g}[/latex] has been created.

The validity of the infant-industry argument depends on whether the gains in economic well-being exceed the costs. Since this is a dynamic argument, we must compare the stream of benefits (i.e., producer surplus) that domestic producers get once their production becomes internationally competitive with the stream of social costs, which are the deadweight losses incurred by the country while the tariff was in effect. Recall that the deadweight losses are the usual production and consumption effects that arise as a result of the tariff. For the infant-industry argument to be valid, the stream of producer surplus (social benefits) must exceed the stream of social costs (deadweight losses) when expressed in present value terms.

While the infant-industry argument is plausible, there are questions about how effective it is in practice. Some observers contend that government should intervene to support emerging industries only if firms are unable to obtain private financing or if there are positive externalities in production. In most business ventures, firms usually suffer losses before they eventually become profitable. Even when they struggle to become profitable, such firms are often able to secure private financing for feasible business opportunities. If firms are unable to find funding, perhaps because financial markets are imperfect, then there may be a role for government in providing financing. In addition, if external benefits result from production, government may intervene to provide support.

If there is good reason for government to support a nascent industry, it must consider which policy is best for that purpose. As we saw before when we compared an import tariff with a production subsidy, it is most appropriate for government to intervene as close as possible to the source of the problem. If the intent is to boost production, a production subsidy would be a superior policy to an import tariff as the net national loss would be smaller. If imperfect financial markets make it difficult to obtain financing, government may provide subsidized loans to fledgling firms. If the problem is that infant-industry firms are losing workers to firms elsewhere in the economy, then government can subsidize worker training.

Another question related to the industry argument is whether the industry will ever become efficient. Observers often contend that the infant industry never grows up. Protected by import tariffs or other policies, producers within the industry often are not motivated to reduce their production costs. While the infant-industry argument makes the case for temporary tariff protection, producers are often successful in lobbying for such protection to be maintained over long periods of time. Considerable dispute remains about the success of the infant-industry case in practice. While Brazilian motor vehicle manufacturing is cited as a failure (Carbaugh, 2015), the Japanese computer and semiconductor industries are reputed to represent cases of successful infant-industry protection (Pugel, 2020).

References

Carbaugh, R.J. (2015). International economics, (15th ed.). Cengage Learning.

Pugel, T. A. (2020). International economics, (17th ed.). McGraw-Hill.

Image Descriptions

Figure 6.4: Protecting an Emerging Industry with a Temporary Tariff.

The image comprises two side-by-side graphs, labelled (a) "The Domestic Market Today" and (b) "The Domestic Market in Future" respectively. Both are supply-and-demand graphs with price (P) on the vertical axis and quantity (Q) on the horizontal axis.

Graph (a) has a downward-sloping demand line (labelled Dd) and an upward-sloping supply line (labelled Sd) that begins one-third of the way up the y-axis, between two horizontal lines extending from the lower half of the axis, labelled PW and PW + t. The intersection of Dd and PW is labelled “E.”

Three quantity levels are marked along the horizontal axis, S2, D2, and D1, with dotted horizontal lines up to the intersections of the price lines with the supply and demand curve, respectively. A horizontal arrow points right from the y-axis to S2; another arrow points left from D1 to D2.

Area b is formed by the y-axis, Sd, S1, and PW. Area d mirrors b, but is a true triangle formed by Ds, PW, and Dd.

Graph (b) is similar, with Sd and Dd, but there is only one price line, PW. The intersection of Dd and PW is labelled “E.” Area g is a shaded triangle beginning on the origin point and formed by Sd and PW and the Y-axis.

[back]

a new industry to which government provides temporary protection until it can produce at costs low enough to compete internationally