Chapter 4: Tariffs

4.2 The Economic Effects of an Import Tariff – The Small-Country Case

One of the key ideas that we have seen with regard to international trade is that it affects different groups in the society differently. Therefore, in our analysis we will identify the effects on domestic consumers and domestic producers. We will measure the economic well-being of these groups using the notion of economic surplus – consumer surplus for consumers and producer surplus for producers, respectively.

Consumer surplus is equal to the difference between what consumers are willing to pay (i.e., the value they put on the product) and what they actually pay for a product (i.e., the market price). Graphically, consumer surplus is equal to the area below the demand curve – which reflects the highest price that consumers are willing to pay for particular amounts of the product – and the equilibrium price in a competitive market. A fall in the market price increases consumer surplus and an increase in price reduces it. (See Figure 1.5: Consumer Surplus in Chapter 1.)

In a similar way, producer surplus is equal to the difference between the minimum price that producers are willing to accept (i.e., the marginal cost of producing particular amounts of the product) and the price they actually receive. Graphically, producer surplus is the area above the supply curve and below the equilibrium price. An increase in the market price raises producer surplus, while a fall in the market price reduces it. (See Figure 1.8: Producer Surplus in Chapter 1.)

We are now ready to examine the effects of an import tariff on consumers, producers, and the nation. We will see that the effects of a tariff are different for a small nation, which has no influence over the world price, from those of a large nation, which is able to influence the world price for the product as a result of its buying power. We will begin by considering the case of a small country.

A small country imports a small proportion of the world supply of the product and is, therefore, unable to influence the world price for the product. As a price-taker, the world price for the imported product is constant from the standpoint of the importing country. In reality, many countries have little or no influence over world product prices. Graphically, we represent the constant world price using a horizontal line in the demand and supply model.

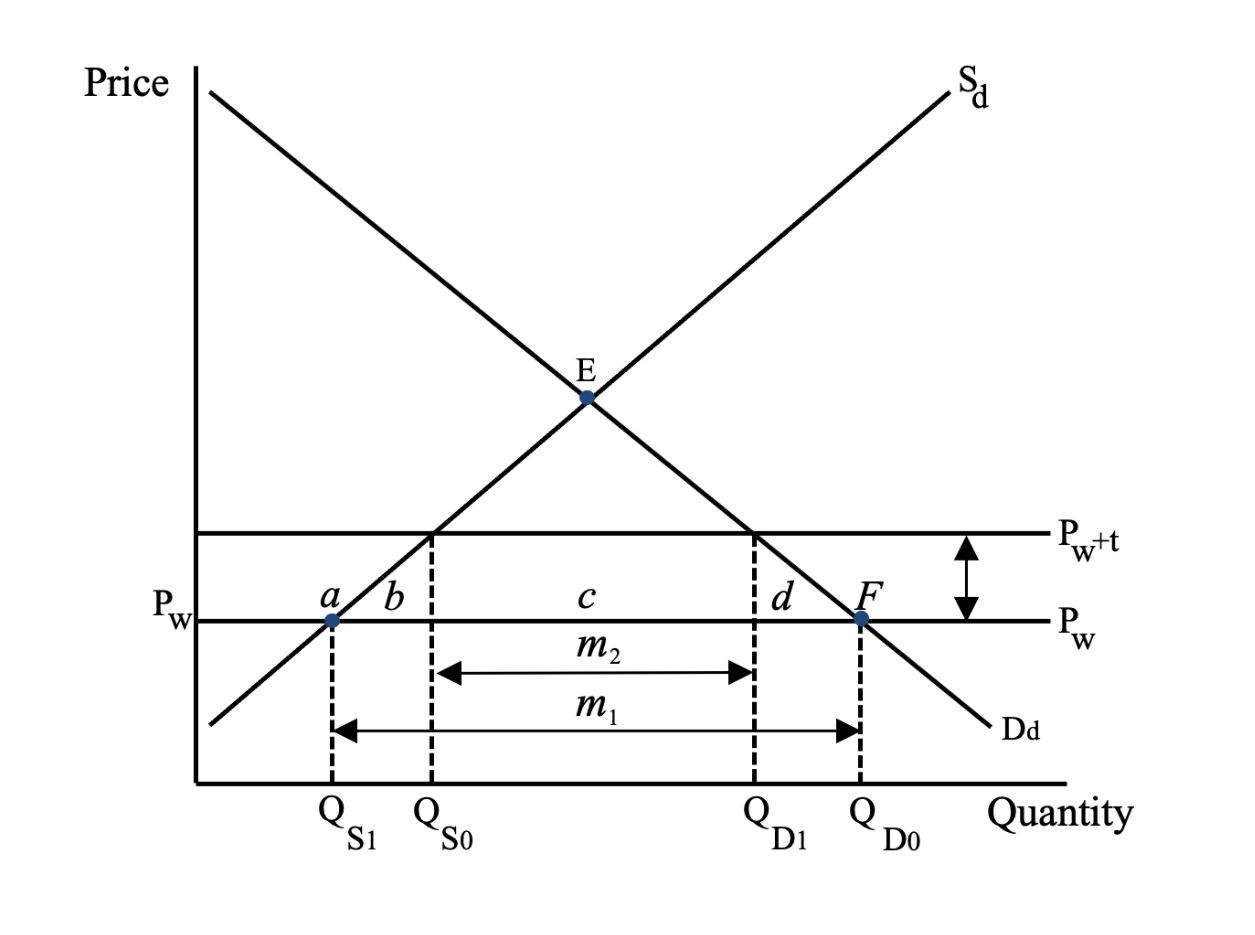

Figure 4.1 represents the domestic market for a product before trade by the intersection of the domestic supply ([latex]\text{S}_{d}[/latex]) and demand ([latex]\text{D}_{d}[/latex]) curves. We determine equilibrium in the domestic market by the intersection of the demand and supply curves at point [latex]\text{E}[/latex]. If the economy is opened to international trade, it can import an unlimited amount of the product at the going world price. That is, the supply of imports is constant at the world price, shown as a horizontal line lying below the domestic equilibrium market price before trade. At the world price, the domestic market equilibrium shifts from Point E to Point F, where the demand curve intersects the world price line, [latex]\text{W}_{p}[/latex]. At this point, the total quantity of the product that is purchased is [latex]\text{Q}_{D0}[/latex], and the quantity supplied by domestic producers is [latex]\text{Q}_{S0}[/latex].

Compared with the situation before trade, domestic consumption increases as a result of the lower world price while domestic production falls. Thus, imports emerge, and the quantity of imports is equal to the difference between [latex]\text{Q}_{S0}[/latex] and [latex]\text{Q}_{D0}[/latex]. With international trade, consumers are better off since they are able to consume more and pay a lower price. Meanwhile, producers experience a decline in their well-being as they supply less at the lower world price. The domestic industry is, therefore, hurt by international competition as production and employment fall.

Suppose the national government gives in to political pressure from domestic producers to provide tariff protection to their industry! Since the world price remains unchanged in the case of a small country, the price on the domestic market rises by the full amount of the tariff – it now becomes [latex]\text{W}_{p}+\text{t}[/latex], where [latex]\text{t}[/latex] is the import tariff. As a result, consumers cut back on purchases of the product to [latex]\text{Q}_{D1}[/latex], as they bear the full burden of the tariff; producers expand their production to [latex]\text{Q}_{S1}[/latex] due to the protective effect of the tariff; and the quantity of imports fall from their pre-tariff levels to the difference between [latex]\text{Q}_{S1}[/latex] and [latex]\text{Q}_{D1}[/latex]. The tariff reduces imports and encourages domestic production. In summary, consumer surplus declines by the sum of areas [latex]\textit{a}+{b}+{c}+{d}[/latex]. Producer surplus rises by area [latex]\textit{a}[/latex].

The loss of consumer surplus is more than the gain in producer surplus – consumers have to pay the price mark-up on both domestic production and imports while producers gain the price mark-up only on domestic production. However, some of what consumers lose in economic surplus is transferred to producers – the loss of area [latex]\textit{a}[/latex] by consumers is redistributed to producers – and therefore is not a loss to the nation. Some of what consumers lose is also transferred to the national government as tariff revenue. As long as the tariff is not high enough to block out all imports, the tariff will generate government revenue equal to the tariff multiplied by quantity of imports, i.e., [latex][(\text{Q}_{S1}-\text{Q}_{D1})*\text{t}][/latex]. While tariff revenue represents a loss to consumers, it is not a loss to the nation as there is a transfer of surplus from consumers to the national government. The tariff revenue is captured by area [latex]\textit{c}[/latex] in Figure 4.1.

If we combine the effects of the tariff on consumers, domestic producers, and the national government, we could determine the net impact of the tariff on the nation (see Table 4.5). If we value each dollar of economic gain or loss the same regardless of the group to which it accrues, we could add the gains and losses to consumers, producers, and government to find the overall effect on the nation.

| Item | Gain/Loss |

|---|---|

| Producer surplus gain or loss | [latex]+\textit{a}[/latex] |

| Consumer surplus gain or loss | [latex]-\textit{a}-{b}-{c}-{d}[/latex] |

| Government revenue | [latex]+\textit{c}[/latex] |

| National well-being | [latex]-\textit{b}-{d}[/latex] |

The net national loss of economic well-being in the case of a small country is the sum of areas [latex]\textit{b}[/latex] and [latex]\textit{d}[/latex] . Area [latex]\textit{b}[/latex] is called the production effect (or protective effect) of the tariff. This represents the fact that some consumer demand is shifted from less expensive imports to more expensive production by domestic suppliers. It captures the additional cost of switching consumption to less efficient domestic production and represents the cost of supporting domestic producers. It is part of what consumers pay, but since neither producers nor the government get this surplus, it is a deadweight loss. Area [latex]\textit{d}[/latex] is called the consumption effect of the tariff. This reflects the loss to consumers stemming from the fall in consumption due to the higher after-tariff price. Area [latex]\textit{d}[/latex] is a deadweight loss because consumers lose surplus without any other group getting it. These deadweight losses are real costs to the nation.

Credit: © by Kenrick H. Jordan and Conestoga College, CC BY-NC-SA 4.0.

Image Descriptions

Figure 4.1: The Economic Effects of a Tariff.

The image is a graph with the x-axis labelled "Quantity" and the y-axis labelled "Price." Two intersecting lines form an X in the graph: the downward-sloping line is labelled "Dd," and the upward-sloping line is labelled “Sd.” The point where Sd and Dd intersect is marked with the letter "E," signifying the equilibrium. A horizontal line below the equilibrium point is labelled "PW+t." Below it, another horizontal line is labelled "PW" The intersection of Dd and PW is labelled F. Four points on the quantity axis are labelled from left to right as "QS1," "QS0," "QD1," and "QD0.” At each intersection of supply, demand, and the world price with and without tariffs are horizontal lines down to the points on the quantity axis.

There is a double-sided horizontal arrow between the two world price lines. A double-sided horizontal arrow labelled "m1" is between the dotted lines of QS1 and QD0, and a double-sided horizontal arrow labelled "m2" is between the dotted lines of QS0 and QD1.

Area a is above the intersection of Sd and PW and below PW+t. Area b is the triangle formed by Sd, PW and QS0. Area c is the rectangle in the middle formed by QS0, PW, QD1 and PW+t. Area d mirrors b, formed by QD1, PW, and Dd.

[back]

a country that imports such a small share of a product that it has no influence on the world price

measures the loss to the domestic economy, and reduction of national well-being, that arises from the subsitution of higher-cost domestic production for more efficient foreign production

the loss in social surplus that occurs when a market produces an inefficient quantity

the loss of economic well-being that occurs due the increase in price and the resulting fall in consumption due to import protection (e.g., tariff)