Chapter 3: Hecksher-Ohlin and Other Trade Theories

3.2 The Shortcomings of the Standard Model as an Explanation of Intra-Industry Trade

The patterns of real-world international trade conform to a significant degree with the predictions of the standard model, which indicate that countries should engage in trade to exploit cost differences that arise from differences in resource endowments and differences in technology and productivity. The standard theory of international trade – including the Heckscher-Ohlin model – suggests that countries should export one type of product or service and import a substantially different type of product. International trade should be inter-industry. And indeed, a lot of international trade takes this form.

However, much trade does not seem to fit well with the standard theory. The theory of comparative advantage – including the H-O theory – suggests that countries similar in resource endowments and technology should not trade a lot with each other. In practice, however, developed countries engage in significant two-way trade in which they individually export and import the same or similar products. This is especially true where these countries are close to each other geographically. The H-O theory does not give a good explanation of two-way trade in similar products or intra-industry trade.

To understand intra-industry trade, we look at models that go beyond comparative advantage and its assumption of perfect competition. In the following sections, we will expand our understanding of trade by considering some theories which incorporate aspects of imperfect competition, which implies that producers have some degree of market power (Pugel, 2020; Carbaugh, 2015). The first theory we will consider is based on product differentiation and monopolistic competition; the second is premised on global oligopoly; and the third is premised on the tendency for firms in an industry to cluster in specific geographic areas. Economies of scale are an important element in all of these cases. Economies of scale, monopolistic competition, and oligopoly will be discussed later.

Review: Intra-Industry Trade

Review your understanding of intra-industry trade by watching this video [13:08].

Source: Marginal Revolution University. (2015, September). Intra Industry Trade. [Video]. YouTube. https://youtu.be/DUmgU_F3Imk?si=ZpQdGof4HJs7zdzt

Did You Know? Economies of Scale

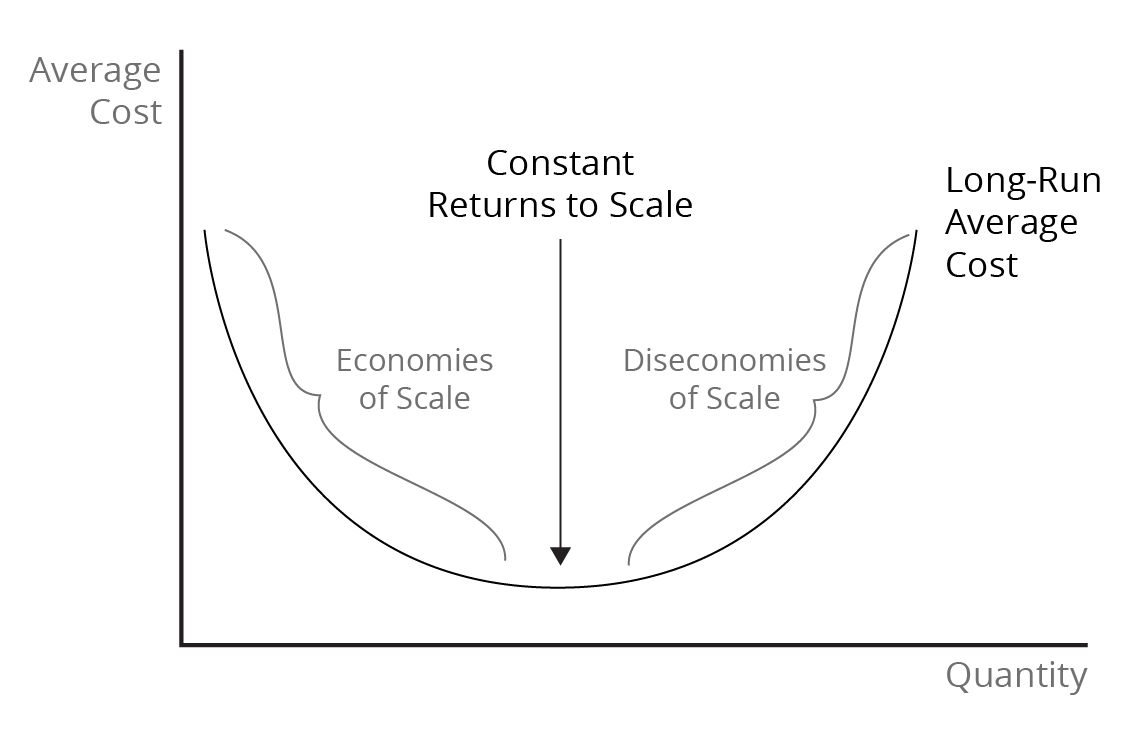

Economies of scale occur when increases of inputs lead to a greater than proportionate increase in production. Assuming that factor prices remain constant, this causes the average cost of production to decline as production increases. Diseconomies of scale arise when increases in factor inputs cause a less-than-proportionate increase in output and a rising average total cost of production. Constant returns to scale occur when increases in factor inputs lead to proportionate increases in cost and output so that the average production cost remains constant regardless of the output level. Economies of scale, constant returns to scale, and diseconomies of scale are depicted in Figure 3.1.

Credit: © by Kenrick H. Jordan and Conestoga College, CC BY-NC-SA 4.0.

We can distinguish between internal economies of scale and external economies of scale. Internal economies of scale result when increases in output by the firm cause its average production costs to decline.Internal economies of scale push firms to become larger so that, if scale economies are substantial, only a few large firms will produce the industry’s output. With the few firms dominating the industry recognizing their interdependence, a key issue will be how much competition results. If the firms in this oligopolistic industry compete vigorously, output will be large and average costs and prices low. On the other hand, if firms collude, output would be smaller, prices would be high, and this situation could last for a long time. The presence of economies of scale can lead to another outcome. If scale economies are not too large, then there may be room for a significant number of firms in the industry. In addition, if the firms in the industry supply many versions of the same basic product, then monopolistic competition results. In this market structure, many firms produce and sell limited quantities of different versions of the basic product. While each firm would have some control over the price of its product, such market power would be temporary, as competition based on price and product quality eventually erodes it. External economies of scale are premised on the size of the industry within a particular geographic area. As industry output expands, the average cost of the typical firm producing the product in that area declines. External economies help explain why firms in some industries cluster in specific areas. External economies can arise if the concentration of firms in a geographic area encourages greater local supplies of particular factors (e.g., specialized labour) to the industry. Some examples of clustering encouraged by external economies are the financial services industry in London and New York City, the movie-making industry in Hollywood, and the information technology industry in Silicon Valley (Pugel, 2020; Carbaugh, 2015).

Review: Trade and External Economies of Scale

Review your understanding of trade and external economies of scale by watching this video [19:07].

Source: Marginal Revolution University. (2015b, September 16). Trade and external economies of scale [Video]. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=jPE9yE9OsME

References

Carbaugh, R.J. (2015). International economics, (15th ed.). Cengage Learning.

Pugel, T. A. (2020). International economics, (17th ed.). McGraw-Hill.

Image Descriptions

Figure 3.1: Economies of Scale: The Long-Run Average Cost Curve

The image is a diagram consisting of a graph with a vertical axis labelled “Average Cost” and a horizontal axis labelled “Quantity.” A smooth, concave curve is centred within the coordinate system, which initially descends steeply, then levels out, and finally ascends gradually, labelled “Long-Run Average Cost.”

The descending portion of the curve is labelled “Economies of Scale.” A vertical arrow labelled “Constant Returns to Scale” points down to the bottom and middle of the curve. Lastly, the ascending portion of the curve is labelled “Diseconomies of Scale.”

[back]

this describes a market where the assumptions of perfect competition — many buyers and sellers, identical products, readily available information, and ease of entry and exit for firms — do not hold; in imperfect competition, firms set prices, may sell differentiated products, and barriers to entry and exit may exist

the reduction in the long-run average cost of production that occurs as total output increases

when the long-run average cost of the firm declines as the output of the firm increases

the situation in which the long-run average cost of the firms decline as the output of the industry increases