Chapter 3: Identify the trends in technology, demographics, consumerism, and shifting world trade patterns and the globalization of business.

3.1. Defining Global Marketing

Before you begin

Before you begin reading, check your understanding of some of the key terms you will read in this chapter:

Toyota has a vehicle for every market

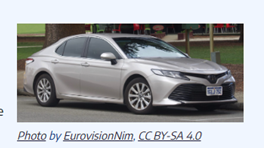

Each market has unique cultural characteristics and contextual circumstances that must be considered. For example, in the United States roads tend to be wide; highways can accommodate a broad array of vehicles with a high number of lanes, and people demand a mix of cars based on their needs. Conversely, in Europe roads tend to be narrow, and the market demands smaller, more fuel-efficient vehicles. Therefore, while a Toyota 4Runner tends to sell extremely well in the United States, it would not be a very popular model in Europe for these very reasons. As a result, Toyota invests billions of dollars every year into market research and market development to make sure they meet the needs and wants of its customers, in each specific country that they sell their vehicles in. This has led to Toyota’s success in the US automotive market, as our earlier case suggested. With their #1 selling sedan, Toyota Camry, a wide array of hybrid models, trucks and SUVs to meet the United States constantly-changing expectations, Toyota is, arguably, the strongest player in the automotive industry.

Now that the world has entered the next millennium, we are seeing the emergence of an interdependent global economy that is characterized by faster communication, transportation, and financial flows, all of which are creating new marketing opportunities and challenges. Given these circumstances, it could be argued that companies face a deceptively straightforward and stark choice: they must either respond to the challenges posed by this new environment or recognize and accept the long-term consequences of failing to do so. This need to respond is not confined to firms of a certain size or particular industries. It is a change that to a greater or lesser extent will ultimately affect companies of all sizes in virtually all markets. The pressures of the international environment are now so great, and the bases of competition within many markets are changing so fundamentally, that the opportunities to survive with a purely domestic strategy are increasingly limited to small and medium-sized companies in local niche markets.

Perhaps partly because of the rapid evolution of global marketing, a vast array of terms has emerged. Clarification of these terms is a necessary first step before we can discuss this topic more thoroughly.

Let us begin with the assumption that the marketing process that you have learned in any basic marketing course is just as applicable to domestic marketing as to international marketing. In both markets, we are goal-driven, do necessary marketing research, select target markets, employ the various tools of marketing (i.e., product, pricing, distribution, communication), develop a budget, and check our results. However, the uncontrollable factors such as cultural, social, legal, and economic factors, along with the political and competitive environment, all create the need for a myriad of adjustments in the marketing management process.

Source:

McCubbrey, D. (2015) Business Fundamentals. The Global Text Project.

Global vs Domestic Marketing

One of the inevitable questions that surfaces concerning global marketing is, how does global marketing truly differ from domestic marketing, if at all?

Historically, there has been much discussion over commonalities and differences between global and domestic marketing, but the three most common points of view upon which scholars agree are the following:

- All marketing is about the formulation and implementation of the basic policies known as the 4 Ps: Product, Price, Place, and Promotion.

- Global marketing, unlike domestic marketing, is understood to be carried out “across borders”.

- Global marketing is not synonymous with international trade. Perhaps the best way to distinguish between the two is simply to focus on the textbook definition of international marketing. One comprehensive definition states that “international marketing means identifying needs and wants of customers in different markets and cultures, providing products, services, technologies, and ideas to give the firm a competitive marketing advantage, communicating information about these products and services and distributing and exchanging them internationally through one or a combination of foreign market entry modes”.

At its simplest level, global marketing involves the firm making one or more marketing decisions across national boundaries. At its most complex, it involves the firm establishing manufacturing and marketing facilities overseas and coordinating marketing strategies across markets. Thus, how global marketing is defined and interpreted depends on the level of involvement of the company in the international marketplace.

Source:

Manuel L. (2023). Global Marketing in a Digital World. Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-Share Alike 4.0 International License.

3.2. Automation and AI (Artificial Intelligence)

What is AI?

Artificial intelligence is a machine’s ability to perform the cognitive functions we usually associate with human minds.

Humans and machines: a match made in productivity heaven. Our species wouldn’t have gotten very far without our mechanized workhorses. From the wheel that revolutionized agriculture to the screw that held together increasingly complex construction projects to the robot-enabled assembly lines of today, machines have made life as we know it possible. And yet, despite their seemingly endless utility, humans have long feared machines—more specifically, the possibility that machines might someday acquire human intelligence and strike out on their own.

But we tend to view the possibility of sentient machines with fascination as well as fear. This curiosity has helped turn science fiction into actual science. Twentieth-century theoreticians, like computer scientist and mathematician Alan Turing, envisioned a future where machines could perform functions faster than humans. The work of Turing and others soon made this a reality. Personal calculators became widely available in the 1970s, and by 2016, the US census showed that 89 percent of American households had a computer. Machines—smart machines at that—are now just an ordinary part of our lives and culture.

Those smart machines are getting faster and more complex. Some computers have now crossed the exactable threshold, meaning that they can perform as many calculations in a single second as an individual could in 31,688,765,000 years. But it’s not just about computation. Computers and other devices are now acquiring skills and perception that have previously been our sole purview.

AI is a machine’s ability to perform the cognitive functions we associate with human minds, such as perceiving, reasoning, learning, interacting with an environment, problem solving, and even exercising creativity. You’ve probably interacted with AI even if you didn’t realize it—voice assistants like Siri and Alexa are founded on AI technology, as are some customer service chatbots that pop up to help you navigate websites.

Video: New Coca Cola Stable Diffusion AI Ad (The AI Examiner)

Transcript is unavailable as this video contains no speech.

Source:

McKinsey & Company (2023, April 24). What is AI? McKinsey Global Institute.

3.3. Global value chains

Global Supply-Chain Management

In today’s global competitive environment, individual companies no longer compete as autonomous entities but as supply-chain networks. Instead of brand versus brand or company versus company, it is increasingly suppliers-brand-company versus suppliers-brand-company. In this new competitive world, the success of a single business increasingly depends on management’s ability to integrate the company’s intricate network of business relationships. Supply-chain management (SCM) offers the opportunity to capture the synergy of intra- and intercompany integration and management. SCM deals with total business-process excellence and represents a new way of managing business and relationships with other members of the supply chain.

Top-performing supply chains have three distinct qualities:

- First, they are agile enough to readily react to sudden changes in demand or supply.

- Second, they adapt over time as market structures and environmental conditions change, and,

- Third, they align the interests of all members of the supply-chain network in order to optimize performance.

These characteristics—agility, adaptability, and alignment—are possible only when partners promote knowledge-flow between supply-chain nodes. In other words, the flow of knowledge is what enables a supply chain to come together in a way that creates a true value chain for all stakeholders. Knowledge-flow creates value by making the supply chain more transparent and by giving everyone a better look at customer needs and value propositions. Broad knowledge about customers and the overall market, as opposed to just information from order points, can provide other benefits, including a better understanding of market trends, resulting in better planning and product development.

Supply Chains: From Push to Pull

A supply chain, the flow of physical goods and associated information from the source to the consumer, refers to the flow of physical goods and associated information from the source to the consumer. Key supply-chain activities include production planning, purchasing, materials management, distribution, customer service, and sales forecasting. These processes are critical to the success manufacturers, wholesalers, or service providers alike.

Electronic commerce and the Internet have fundamentally changed the nature of supply chains and have redefined how consumers learn about, select, purchase, and use products and services. The result has been the emergence of new business-to-business supply chains that are consumer-focused rather than product-focused. They also provide customized products and services.

In the traditional supply-chain model, raw material suppliers define one end of the supply chain. They were connected to manufacturers and distributors, which, in turn, were connected to a retailer and the end customer. Although the customer is the source of the profits, they were only part of the equation in this “push” model. The order and promotion process, which involves customers, retailers, distributors, and manufacturers, occurred through time-consuming paperwork. By the time customers’ needs were filtered through the agendas of all the members of the supply chain, the production cycle ended up serving suppliers every bit as much as customers.

Driven by e-commerce’s capabilities to empower clients, most companies have moved from the traditional “push” business model. The traditional product-centric and delivery-driven process by which manufacturers, suppliers, and distributors flowed products to the end customer., where manufacturers, suppliers, distributors, and marketers have most of the power, to a customer-driven “pull” model. The new customer-driven process where all supply chain participants are directly connected to the end customer. This new business model is less product-centric and more directly focused on the individual consumer. As a result, the new model also indicates a shift in the balance of power from suppliers to customers.

Whereas in the old “push” model, many members of the supply chain remained relatively isolated from end users, the new “pull” model has each participant scrambling to establish direct electronic connections to the end customer. The result is that electronic supply-chain connectivity gives end customers the opportunity to become better informed through the ability to research and give direction to suppliers. The net result is that customers now have a direct voice in the functioning of the supply chain, and companies can better serve customer needs, carry less inventory, and send products to market more quickly.

Source:

Northeast Wisconsin Technical College (2023). Global Supply-Chain Management. Global Business – Chapter 9.

Video: Comparing Value Chain and Supply Chain. QStock Inventory.