10 Universal Design for Learning (UDL)

Introduction

The rigidity of curriculum, assessments and structured learning, among many things in the education system, serves a purpose: It provides a framework for educators to assess students’ understanding of course content. However, the lack of choice and expression can negatively impact intrinsic motivation (Ryan & Deci, 2000). Self-determination theory (SDT) asserts that students have basic needs for competence, including the feeling of effectiveness and mastery in their learning, relatedness, connecting with others and course material and autonomy, including ownership of their knowledge, amongst other needs. The basic needs motivate students to grow, learn and achieve success in their academics. (Legault, 2017). In their research, Hanewicz et al. (2017) showed that providing students with a choice of assignments created a positive learning experience for them and motivated them to continue learning in their educational journey. The element of allowing student autonomy and choice to express their learning and comprehension of course material is a central thesis of Universal Design for Learning (UDL).

What is Universal Design for Learning (UDL)?

Universal Design for Learning (UDL) leverages the neuroscience of learning to enhance and personalize education for everyone (CAST, 2018). UDL views student learning as a continuum of starting points based on age, prior knowledge, cognitive development, physicality and social experience. In this respect, UDL empowers educators to modify curriculum elements to personalize students’ education (Rose & Dolan, 2000). Supporters of the UDL recognize how traditional approaches to instruction limit the flexibility students need to complete their studies; inflexibility creates barriers to learning (La et al., 2018).

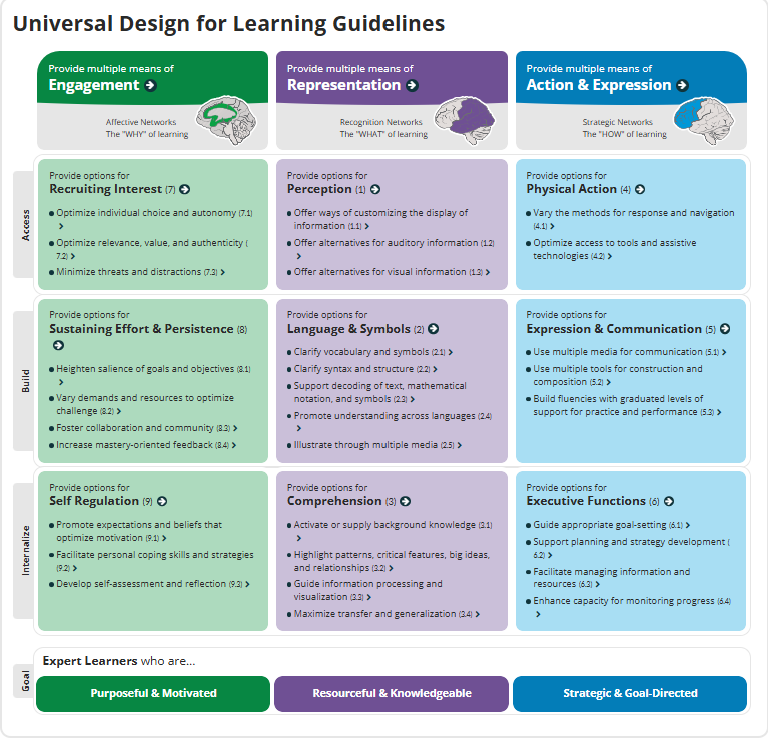

Universal Design for Learning (UDL) combines theory and empirical data to make a case for curriculum and learning access to all learners, regardless of how old they are, what skills they have or other demographic factors (Ontario Ministry of Education, 2013). There are three main principles of UDL: Engagement of learners, multiple representations of content, and enabling action and expression (CAST, 2018; see Figure 1).

Engagement

UDL emphasizes internal motivation to learn through the intersection of genetics, environment, culture, prior knowledge and other factors that constitute human individuality (CAST, 2018). Motivated learners desire self-directed learning and actively create learning goals (La et al., 2018). Students who are internally motivated in their education are more likely to engage in content and apply newly acquired knowledge. The variation in student motivation reflects the UDL principle of engagement. Student engagement allows educators to meet students at their point in learning and facilitate robust yet individualized learning through collaboration while supporting self-directed learning (CAST, 2018).

Representation

Learner characteristics not only affect engagement but also impact how learners obtain and process information. The learner’s comprehension of the information is subjective and limited (CAST, 2018). Employing multiple means of representation, such as pedagogical approaches and multimodal sources of information, supports student learning by accommodating diverse comprehension styles and providing adaptable options (Almeqdad et al., 2023).

Action and expression

Learners’ individuality extends to expressing existing and new knowledge (CAST, 2018). The UDL principle of action and expression recognizes that students have different communication strengths. For instance, some excel in writing while others are more effective verbally. The action and expression principle supports this diversity by offering various ways for students to express their learning, enabling them to confidently apply their knowledge (Almeqdad et al., 2023 & La et al., 2018).

Figure 1 The Principles of Universal Design for Learning

Source: CAST (2018)

UDL and assessments

Integrating Universal Design for Learning (UDL) principles into assessment strategies is pivotal in cultivating an inclusive and equitable academic atmosphere (CAST, 2018). For instance, some educators use apply UDL principles to authentic assessments[1] in order to accommodate the diversity of learners’ experiences and remove barriers to learning through choice and expression.

Attributes of UDL and assessments

The following attributes of UDL and their connection to assessments were adapted from Gordon et al. (2014):

Construct relevance:

Educators design authentic assessments to be intrinsically motivating, offering pertinent tasks that reflect students’ interests. This alignment with personal motivation, specific skills and knowledge ensures that the assessments are meaningful and that there is sustained engagement and a vested interest in learning.

Ongoing and progress centric:

Authentic assessments are continuous rather than episodic. They prioritize tracking the learner’s progress over time, providing insights into their evolving understanding and mastery of the subject matter. The assessments evaluate the final product and the process leading to it. This dual focus ensures a comprehensive understanding of the learner’s capabilities, including their strategic and critical thinking skills.

Expression through diversity:

UDL empowers students to convey their understanding that aligns with their unique communicative strengths by advocating for multiple means of action and expression. UDL-based assessments are adaptable to accommodate the diverse needs of learners. This flexibility acknowledges the diversity of student expression and supports the demonstration of knowledge in various forms.

Application in real-world scenarios:

The culmination of these UDL principles in authentic assessments allows students to apply their knowledge in real-world contexts confidently. This practical application reinforces the relevance of their learning and the transferability of skills beyond the classroom.

A framework for individuality and learner involvement:

By weaving UDL into the fabric of assessment design, educators establish a dynamic framework that adapts to and celebrates the individual learning trajectories of each student. This personalized approach recognizes and values every learner’s journey, ensuring the educational experience is as unique as the students themselves. UDL assessments engage learners by involving them in the assessment process. This involvement can range from self-assessment to peer feedback, fostering a sense of autonomy and responsibility towards their learning.

Ineffective assessments contradict UDL principles by offering a one-size-fits-all approach rather than accommodating how students learn and express their knowledge, and this can lead to a lack of motivation engagement and, ultimately, a barrier to learning for those who do fit the narrow criteria of a poorly designed assessment (Tai et al., 2021). By adopting flexible, performance-based assessments, providing students with the means to engage the assignment and content, presenting information in different ways to cater to diverse learners, and providing various methods for students to demonstrate what they know, educators can create learning experiences that honour the potential of every student.

The problem with ineffective use of assessments

The ineffective use of assessments, especially formative assessments[2], can create non-inclusive learning environments. When educators use assessments ineffectively, students face barriers to learning that can create negative learning experiences for them. For instance, they may develop a poor student mental mindset and believe they don’t know how to learn because their teachers may not have given them to tools, strategies and habits (Ontario Ministry of Education, 2010) to do so. These negative experiences can have a negative impact on self-regulation and metacognition. In terms of formative assessments, ineffective ones can prevent students from effectively judging their understanding of the learned concepts; they can also encourage students to distrust their teachers because students may perceive their assessments as unfair or unsupportive (Chew & William, 2020). Furthermore, if the assessment is designed poorly, it could be biased and inconsiderate towards the diverse ways that students can and may want to demonstrate their learning (Areekkuzhiyil, 2021).

This is especially important with regard to formative assessments, since they are ongoing, frequent and measure student learning achievement and progress. If formative assessments are ineffectively designed and used, then they may not provide unequal opportunities for students to succeed and thrive in their educational pursuits. For example, formative aspects of authentic assessments, underpinned by UDL, are characterized by their ability to resonate with students personally, fostering a deep and meaningful engagement with the learning material because they reflect real-world experiences and relevance to students. If these assessments are designed or used ineffectively, then they may not actually allow all students to participate due to the diversity of cultures and life experience that makes the real-world experiences, upon which the assessments are based on, real for some learners and not others.

Test Your knowledge!

References

Areekkuzhiyil, S. (2021). Issues and concerns in classroom assessment practices. Eductacks, 20(8), 20-23.

Almeqdad, Q.I., Alodat, A.M. Alquaraan, M.F., Mohaidat, M.A., & Al-Makhzoomh, A.k. (2023). The effectiveness of universal design for learning: A systematic review of the literature and meta-analysis. Cogent Edcuation, 10(1), 2218191. https://doi.org/10.1080/2331186X.2023.2218191

CAST (2018). Universal design for learning version 2.2. Retrieved from https://udlguidelines.cast.org/

Chew, S., & Willam, C. (2020). The cognitive challenges of effective teaching. The Journal of Economic Education, 52(1), 17-40. https://doi.org/10.1080/00220485.2020.1845266

Ellis, A. K., & Bond, J. B. (2016). Assessment. In Research on educational innovations (5th ed.). (pp. 66-78). 77Routledge.

Gordon, D., Meyer, A., & Rose, D. (2014). Designing for all: What is a UDL curriculum. In D. Gordon, A. Meyer, & D. Rose, Universal Design for Learning: Theory and Practice (pp. 127-155). CAST Professional Publishing.

Hanewicz, C., Platt, A., Arendt, A. (2017). Creating a learner-centered teaching environment using student choice in assignments. Distance Education, 38(3), 273-287. https://doi.org/10.1080/01587919.2017.1369349

La, H., Dyjur, P., & Bair, H. (2018). Universal design for learning in higher education. Taylor Institute for Teaching and Learning. Calgary: University of Calgary

Legault, L., (2017). Self determination theory. In V. Zeigler-Hill, & T. Shackelford (Eds.), Encyclopedia of personality and individual differences, (1-9). Springer. DOI 10.1007/978-3-319-28099-8_1162-1

Ludwig, N. W. (2014). Exploring the relationship between K-12 public school teachers’ conceptions of assessment and their classroom assessment confidence levels (Order No. 3579798). Available from ProQuest Dissertations & Theses Global. (1513993136). Retrieved from http://search.proquest.com.uproxy.library.dc-uoit.ca/dissertations-theses/exploring-relationship-between-k-12-public-school/docview/1513993136/se-2

Ontario Ministry of Education. (2010). Growing success: Assessment, evaluation and reporting in Ontario schools. (1st edition). http://www.edu.gov.on.ca/eng/policyfunding/growSuccess.pdf

Ontario Ministry of Education (2013). Learning for all: A guide to effective assessment and instruction for all students, kindergarten to grade 12. https://files.ontario.ca/edu-learning-for-all-2013-en-2022-01-28.pdf

Rose, D.E. & Dolan, B. (2000). Universal design for learning: Associate editor’s column. Journal of Special Education Technology, 15(4), 47.

Ryan, R., Deci, E., (2000). Intrinsic and extrinsic motivations: Classic definitions and new directions. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 25(1), 68-78.

Simmons, C.D. Willkomm, T., &Behling, K.T. (2010). Professional power through education: Universal course design initiatives in occupational therapy curriculum. Occupation Therapy Health Care, 24(1), 26-96. https://doi.org/10.3109/07380570903428664

Tai, J., Ajjawi, R., & Umarova, A. (2021). How do students experience inclusive assessment? A critical review of contemporary literature. International Journal of Inclusive Education, 1-18. https://doi.org/10.1080/13603116.2021.2011441

- Authentic assessments involve activities that are centred on real-life situations, problems and experiences and accurately measure and reflect what students should be learning (Ludwig, 2014; Ellis & Bond, 2016) ↵

- Formative assessments are different from summative assessments in that they are ungraded. Both students and teachers use them in an ongoing and frequent manner in order to to gain feedback about learning, analyzing that feedback and making necessary adjustments that improve student achievement (Ludwig, 2014). ↵