By the end of this unit, participants will be able to:

- Have basic knowledge of the history and relevance of design thinking approaches.

- Appreciate the role of design processes in addressing complex problems.

- Have the ability to use basic design frameworks.

Background

Unit 9 is about the role of design processes in transformation. Design thinking can be seen as a key tool for defining problems and generating ideas and interventions as well as prototyping solution and testing them. This section begins with a brief history of design thinking methodologies and the study group dynamics and their combined application to problem-solving in complex systems. The rest of the unit focuses on more contemporary applications of design-thinking to addressing organizational or social challenges.

We introduced in Unit 2 the notion that human systems are increasingly connected, complex and interdependent. Like cars travelling at high speed and following each other too closely on the highway, time and space have been compressed, the lags and gaps have disappeared: any sudden move is likely to trigger a large-scale collision. This increasingly tight-coupling has immediate consequences on both the magnitude of the consequences of possible natural and social disasters and the type of approaches needed to address them. Approaches rooted in complexity science directly challenges hierarchical, linear and mechanical thinking that inform standard commercialization models and innovation processes: solutions need to be informed by an understanding of complexity, systems and of humans’ role in complex systems.

Cross-sector and interdisciplinarity collaborations are crucial in this context: wicked problems cannot be solved by individual organizations or within sectoral and disciplinary silos (Unit 5). Social needs are rapidly outpacing social systems’ capacity to address them. Without approaches that are devised to tackle the complexity of systemic issues, there exists a risk of failing to develop sustainable and efficient solutions.

Addressing complexity is a matter of acquiring the conceptual tools to understand that systems

are made up of interrelated, interdependent parts and yet, they cannot be understood merely as a function of their individual components. In addition to the nature of their parts, systems are also defined by their dynamics, their embedded structure and their purpose. As we have seen in Units 6 and 8, developing strategies to intentionally shape complex systems also requires sustained attention to the fact that the impact of innovations cannot always be foreseen, i.e. that systems are emergent.

The best way to avoid missteps is thus to dedicate time to mapping systems and stakeholders (Unit 4) and formulating a theory of change (Unit 8) that takes into consideration what we know about human dynamics and social processes to create the conditions in which problem solving is best supported. Design processes provide another key instrument for intentional systemic change.

Core Concepts

Mega-messes

Standard approaches to social innovation and transformation tend to revolve around what have become known as ‘change-labs’, ‘design labs’ and ‘social innovation labs’. Design labs have their origins in theories that emerged in the first half of the 20th century: complexity and group dynamics theory. On the one hand, social psychologists study group dynamics to determine the conditions under which people work together, why they make the decisions they do and how we can work more effectively in teams. On the other hand, complexity theorists’ study and model interactions in context that are not deterministic.

The psychology of group dynamics and complexity theory came together for the first time in Eric Trist’s discussion of what we have called ‘wicked problems’ – i.e. problems that emerge in ‘wicked environments’ – and what he called ‘mega-messes’. Trist assumed that mega-messes could only be tackled through “whole system problem solving”: seemingly intractable social and environmental problems are the result of system dynamics over which no individual, nor even group of individual has much control. More importantly, no single individual, institution or even government on their own can provide a solution to wicked problems. Faced with the enormity of the task and to make sure that all relevant aspects of the system are being considered, the solution requires the perspectives and involvement of all stakeholders.

“We act like systems in creating large scale problems, but we act as individuals in trying to solve them” – Eric Trist.

Whole System Approaches

Trist’s work led to the creation of a range of “whole system” approaches, all of which are designed to bring together the actors who have an interest in a particular situation and who bring a necessary perspective to the challenge. These processes, he assumed, could be generalised to every situation:

- Get the whole system into the room.

- Focus on common ground – park differences.

- Build a shared understanding of past and present.

- Imagine future possibilities.

- Engage in action planning together.

Here are some recent examples of whole systems approaches:

Design Thinking

The notion of design is very often used to talk about the processes that lead to the creation of new objects or spaces. This notion has more recently been used in the context of organizational development to describe processes associated with group-based problem solving.

Design processes go far beyond the application of a specific logic or type of analysis to problem-solving: they can also be seen as involving the opportunity to feel, sense, create and engage imagination. Unlike linear logics and analyses, design can lead to surprising discovery and revolves around deliberations that can be exciting and motivating in the effort to produce change where it is needed.

Tim Brown of IDEO (UK) and others, including the Canadian designer Bruce Mau, were among the first to introduce the idea that design can be used to effect systems transformation and the change needed to resolve complex problems in wicked environments. In the context of social innovation, some researchers argue that design thinking is especially useful when informed by an understanding of group dynamics. Combining design thinking with ‘whole systems’ approach sets the condition for collaborative work to address wicked problems.

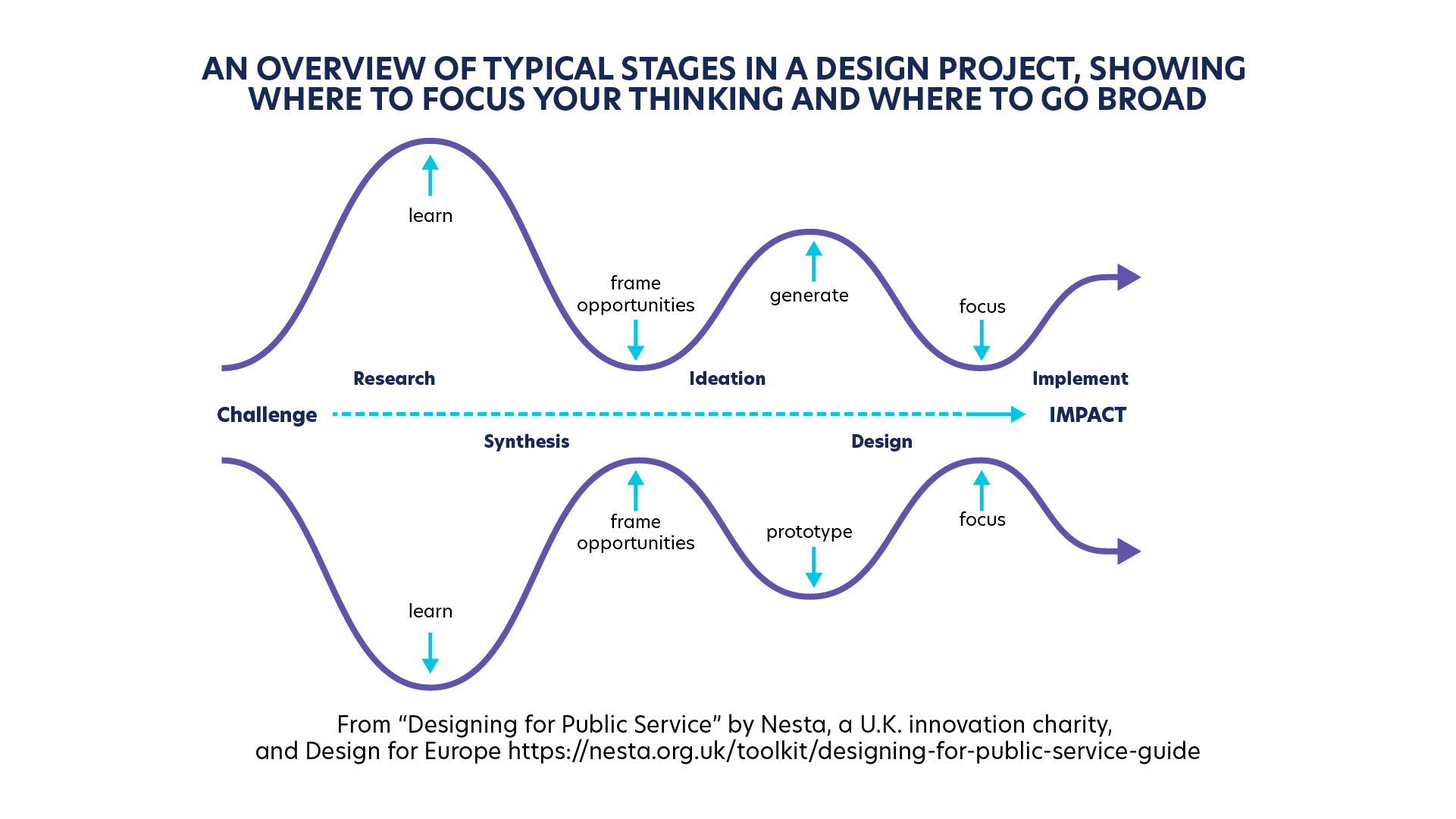

Figure 9.1. From “Designing for Public Services” by Nesta, a U.K. innovation charity and Design for Europe https://www.nesta.org.uk/toolkit/designing-for-public-services-a-practical-guide/.

There are different versions of the design thinking process, but the approach can be generalised. Design starts with research, i.e. the collection and analysis of data designed to ensure a shared understanding of the issue to be resolved and revolves around learning, discovering, empathizing. This informs problem definition, which typically takes the form of a design brief. The next steps revolve around ideation, prototyping and testing. Each of these steps and the process as a whole, is iterative, which means that they can be repeated at any stage and that the progression does not need to be linear.

Change-Labs, Design Labs and Social Innovation Labs

The word ‘Lab’ may connote ways of doing that are associated with minutiae, rigor and impact but their basic purpose is experimentation: they are spaces to try new ideas. Traditionally, laboratories have been spaces dedicated to research, development and experimentation typically associated with the natural sciences and technological fields like engineering and medicine which require precise and highly sophisticated instruments as well as controlled environment. But as an experimentation space, “labs” they can in principle take a variety of forms and they have application in contexts far beyond those of natural sciences and medicine. change-, design- and ideas-labs are widely used for social and ecological problem-solving and they are associated with activities that involve a range of academic disciplines, including disciplines in the social sciences, humanities and arts.

Design labs are sometimes simply called ‘social innovation labs’ or ‘change labs’, or they may bear the name of a specific problem they need to address, e.g. ‘housing lab’, ‘ecological transition lab’. Irrespective of the name they are given, design labs need “equipment” and “methods” that are adapted specifically for research and development of solutions to systemic problems that require social innovation.

For instance, because wicked societal issues have their roots in structures that can be spread across a system, research, data collection and data analysis need to have a broad base and will require the support of staff who can work in multidisciplinary contexts and understand when to secure additional expertise and knowledge needed to learn what is needed to frame the question that underpins design. Likewise, the processes involved in ideation as well as the design and implementation of solutions to complex societal issue, i.e. social innovation processes need to be structured so as to make place for the diversity of input and perspectives that underpin co-creation and resort to methodologies such as bricolage (see Unit 3) and rapid prototyping, all the while remaining focused on action.

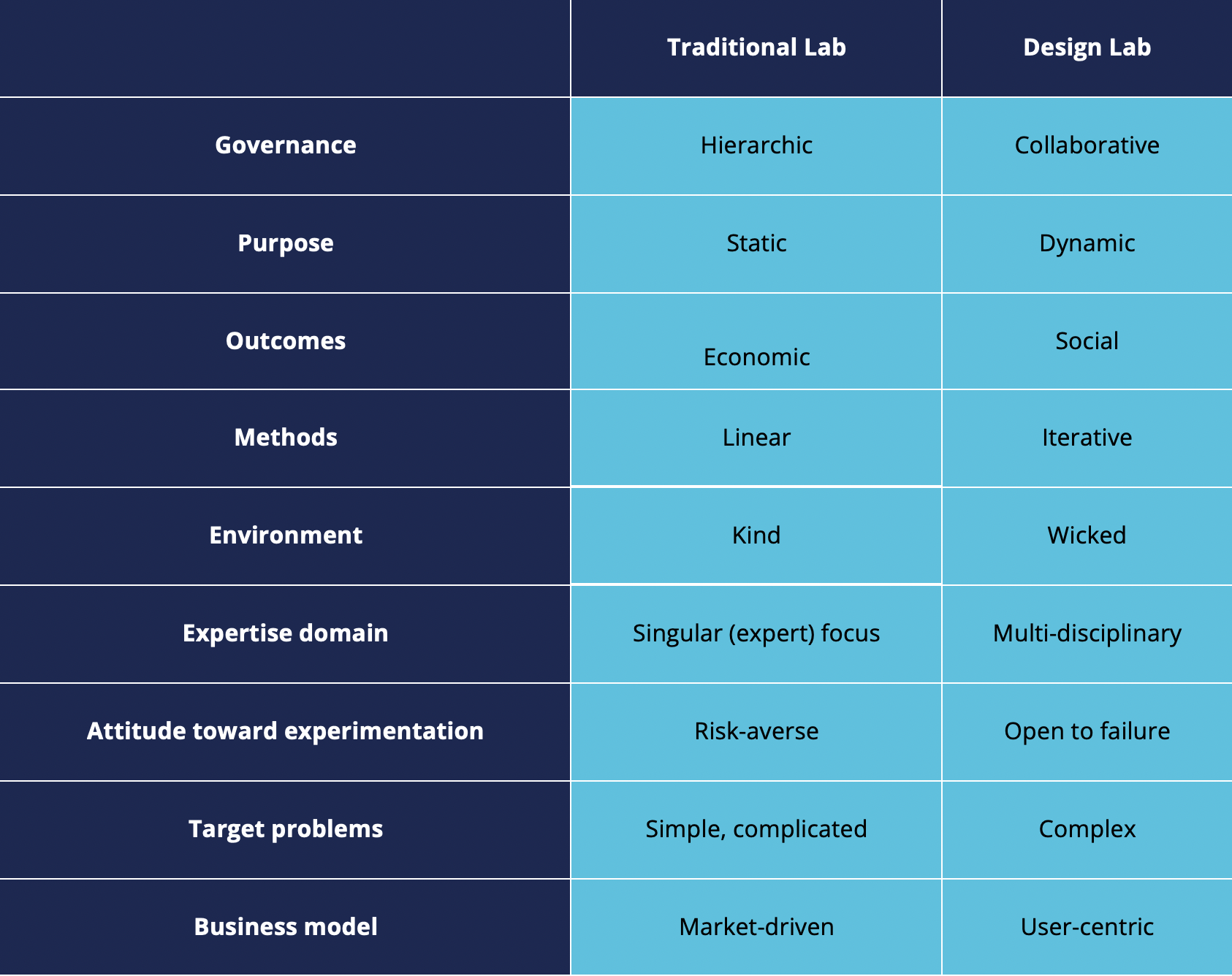

Traditional Research and Development (R&D) vs Design Labs

Social innovation, design and change labs combine aspects of whole systems approaches and design practices. They provide an alternative to traditional organisational “research and development” or R&D strategy and leverage approaches that are intended to bolster change and transformation in organisational settings that can become hierarchic, static and bureaucratic over time.

For example, labs may foster interactions that are highly collaborative rather than top-down, which is a condition to increase equity when it comes to the capacity to include and consider the diversity of perspectives involved in a complex ecosystem. Likewise, the design philosophy that underpins rapid prototyping methods is rooted in the idea that we need to embrace the full extent of experimentation, which includes both the willingness to fail and acknowledgement of the fact that design is an iterative process. This stands in contrast with traditional approaches to organisational research and development management, especially in the social sector, which tend to be risk averse.

Key to balancing co-creative processes when dealing with complex challenges is adopting approaches that are not linear and making space for iterative and emergent processes that are highly dependent on feedback loops. These approaches are generally best supported in organisations where cultures reward continuous learning and evaluation.

Figure 9.2. Traditional vs Design Labs.

Lab approaches have become increasingly popular over the last decade. However, when it comes to social problems, design labs and the social innovation more generally speaking are not a “Holy Grail”. The lab process is designed to address wicked social and environmental challenges – and work towards social innovations that have transformational potential across the ecosystem. However:

- Design labs do not provide instant solutions. The purpose of blending whole systems approaches and design practices and to setup social innovation labs is not to provide quick solutions to easy problem, but the opposite. Design labs are needed to address societal issues such as health crises, poverty and housing, but they require considerable efforts to setup and the results may take years to start taking shape.

- Labs are not inexpensive. They are resource-intensive in terms of research and facilitation, among other things.

- Design labs are not a panacea/cure-all. They work particularly well for complex, messy, interconnected challenges for which traditional innovation processes and the logic of supply and demand seem ineffective and who seem to have no specific owner. They need to be designed to fit the specific context and situation.

It is not possible to foresee the totality of consequences, including bad ones, a social innovation can have. We do our best to avoid missteps by “bringing the whole system into the room”, using what we know about human dynamics, complexity and social processes to create the conditions in which problem solving is best supported.

Eric Trist’s approach combines group dynamics and complexity theory in the idea of whole system problem solving. This involves:

- Getting the whole system into the room.

- Focusing on common ground – park differences.

- Building a shared understanding of the past and present.

- Imagining future possibilities.

- Planning action collectively.

Design thinking is a tool that can be used to map out a project, which involves the collection of data to define the problem (empathize), the creation of a design brief to describe the problem (define) and rapid prototyping, i.e. testing things out in simulation or in small settings to iterate towards a pilot for testing at scale (ideate, prototype and test).

Social innovation, design and change labs are spaces (virtual or real) created to understand, hypothesize and to experiment. They usually combine multiple approaches: they adopt broad-based research, co-creation methodologies that are inclusive of diverse inputs, rely on bricolage and may apply action focused rapid prototyping. They typically rely on multi-disciplinary research and support staff with high levels of expertise who are able to support continuous learning and evaluation.

Slides

Partner Engagement

Activities

References