By the end of this unit, participants will be able to:

- Identify the structure of the process of social innovation from the inception of an idea to the resulting transformation.

- Appreciate the ways to enable decision making and the role of engaging unusual allies.

- Distinguish between innovation growth and innovation spread (scaling up, scaling out, scaling deep and scaling wide).

- Recognize windows of opportunity in social innovation contexts and leverage them to an advantage.

Background

Unit 6 revolves around a case study based on the Registered Disability Savings Plans (RDSP) we briefly described in Unit 4, an initiative aimed at systems innovation that came out of the efforts of the Planned Lifetime Advocacy Network (PLAN). Participants’ learning will not be effective if they haven’t read the case ahead of time. Students are also required to watch an interview with Al Etmanski about his and Vicky Cammack’s work with Planned Lifetime Advocacy Network (PLAN).

The premise of PLAN was that advocacy work focused on human rights alone will not create the type of change those who have disabilities would most benefit from because it leaves untouched issues of isolation and loneliness which affect them most immediately. The key insight driving PLAN’s approach was that improving the lives of more people with disabilities was not a matter of creating or scaling program that help individuals overcome isolation and loneliness and the personal level, but by transforming the systems that create the conditions that lead people with disabilities to feel isolated and lonely in the first place.

Specifically, PLAN’s strategy was to challenge the existing system by working at the level of policy to transform the underlying structures that maintain the exclusion of people living with disabilities in the current system. PLAN targeted the financial future of children with disabilities as a key lever and focused on the relevant institutional issues to create significant and positive change for all those living with disabilities and their families. Their effort led to the creation of a new financial instrument – the Registered Disability Savings Plan – that was intended as a transformative, systems-level innovation. The process of creating this new instrument in turn sparked a nationwide dialogue about the notion of belonging and forced a deeper look at other connected social issues that were in dire need of systemic adjustments.

The case of PLAN highlights the critical role of “systems mediators” (referred to in the video as an “institutional entrepreneur”) to work across scales to create political, cultural and economic changes at the level of systems. Systems mediators need to be equipped to recognize windows of opportunities, manage emergence and understand how changing one part of a complex system can have influence on multiple, interconnected parts – often in unintended ways- to create significant systems change.

Core Concepts

Systems Mediators

Enabling systems to evolve and transition in ways that generate transformative innovation and increased well-being and prosperity requires a constellation of strategies and competencies for “systems mediation”. Successful systems mediators generally:

- Have the ability to shift their focus to attend to the various levels of the system as required in context and to also engage with that system as a whole;

- Are aware and tolerant of the cyclical and iterative nature of innovation;

- Recognize that achieving system-wide impact involves managing uncertainty and emergence by nurturing resource and action networks and carefully paying attention to opportunities as they open across social, cultural, economic and political landscapes.

Emergence

In real life, systems-change rarely happens as a result of top-down, pre-conceived strategic plans, nor through the actions of a single individual or organisation. Change begins as a result of local actions springing up simultaneously across an ecosystem. As long as these changes remain disconnected, the scope of their impact remains limited at best. However, when changes become connected, the effects of local actions can emerge at the level of the system and their impact is no longer local, but systemic or comprehensive.

Emergent phenomena typically appear abruptly and unexpectedly. For instance, consider how sudden the fall of the Berlin wall was, how abrupt the end of the Soviet Union and how quickly corporate power came to dominate globally in the 20th century. In each case, a vast number of local actions and decisions were involved. Most happened in contexts that made them invisible and unknown to each other and none of them, on their own, was powerful enough to transform the system as they did collectively. Their combined power emerged only when local changes, spread across the system coalesced. What had not been accomplished by intentional efforts involving diplomacy, politics and protests suddenly materialised, out of nowhere, surprising most.

Emergent phenomena have the following characteristics:

- Emergent phenomena bring about change, or have an impact that cannot be reduced to what their parts effect individually at a local scale, i.e. the capacity of the whole is not simply the collection of the capacities of its parts.

- Emergent phenomena have more impact than their parts have, even when we consider the sum of their impact (the whole is greater than the sum of its parts);

- Emergent phenomena take forms that are unexpected.

Emergence in systems is part of what explains the lack of control humans have over systems. Emergence is also the reason why we can only contribute to the change we want to see by connecting across sectors with “the other parts”, i.e. with people and organisations who are engaged in different regions of the system. Together, we can achieve more than the sum of our individual efforts.

Innovation Growth

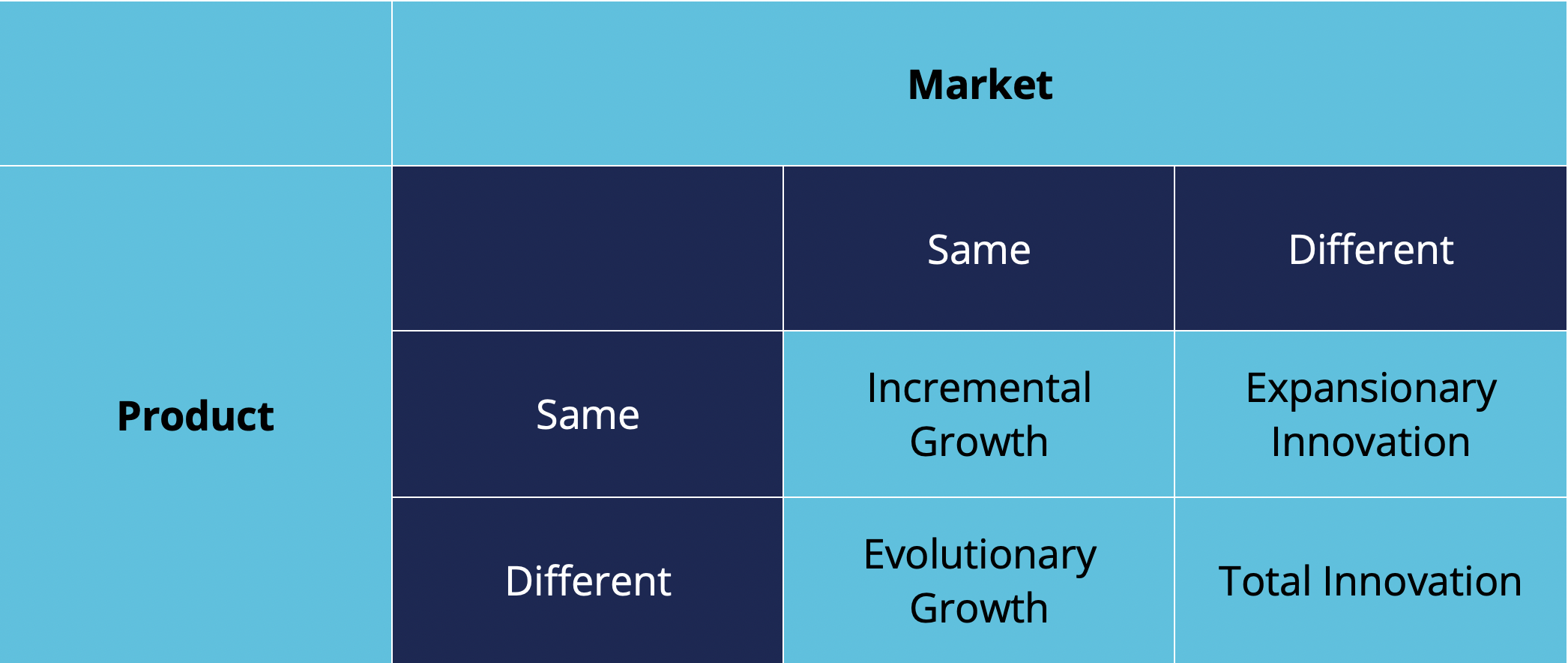

“From Total Innovation to Systems Change – The Case of the Registered Disability Savings Plan (RDSP)” introduces the notion that RDSP amounts to a “total innovation”.

What makes RDSP a total innovation is the way it grows.

What it means for an innovation to grow can be two things. On one hand, it can mean that the product or program itself evolves, i.e. that it changes over time because different versions of the products or different iteration of the program are introduced. On the other hand, we may also say that an innovation grows because its market expands over time as the number of users increases. Because the market can grow while the product stays the same and vice versa, there are four possible meanings to “innovation growth.”

Figure 6.1. Innovation Growth.

Incremental growth occurs when an organization continues to supply users with the same product or service, but tries to encompass a larger share of the market.

Evolutionary growth involves introduction of a different product into the same market.

Expansionary innovation refers to the introduction of the same product into a new market.

Total Innovation happens when an organization increases their impact by transforming both the product and the market.

One example of total innovation was the Nintendo Wii. With the Wii, Nintendo moved away from improving on the standard gaming consoles and reused existing technologies (motion sensor, tv screens and wi-fi) to create an entirely new type of entertainment system that was adopted by people who with no interest in video games. Likewise, RDSP can be understood as a total innovation in the sense defined above. PLAN introduced a new product: they moved aways from a model that revolved around providing services to people with disabilities and pushed for the creation a new type of financial tool. They also changed their market: instead of targeting only people with disabilities and provide them with support, RDSP was also intended to be used by the parents and guardians of people with disability to help them ensure the financial future of those in their care.

In a Social Innovation Context, Scaling is not just Growth

More is involved in social innovation than mere product evolution or market expansion or even their combination. As a social innovation RDSP was in fact transformative and in that respect its “scaling” was not just a matter of growth. Social innovation is typically designed to “spread across systems” and to transform the problem they aim to address. In doing so, Social innovation reshapes social reality.

Social innovation involves multifaceted and iterative processes intended to anchor, lengthen and widen the impact of a new product or service that is expressly designed to tackle multiple aspects of a systemic problem. As such and in order to be transformative, social innovation requires efforts that go much beyond the logic of “adoption” or “dissemination” for new or improved products, ideas, services.

One defining feature of social innovation the role of strategic relationships that are crucially important for achieving the sort of broader systemic impact that is associated with spreading or scaling. In other terms, social innovation can only really spread across a system that is connected. But what is involved in spreading social innovation across a system can’t be reduced to connectivity either and this is where a deeper understanding the role of system mediators (see above) in scaling social innovation is useful.

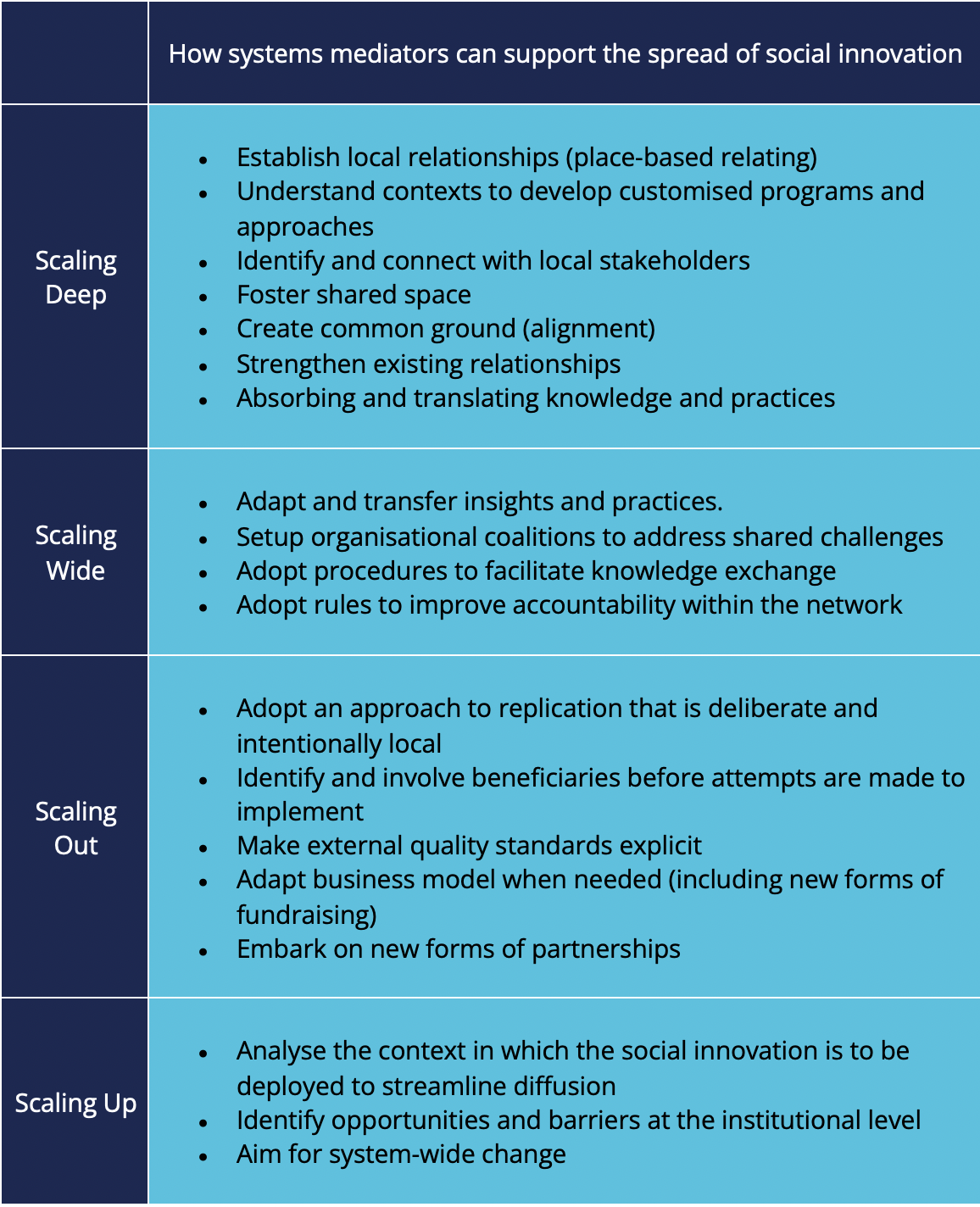

System mediators may support the spread or scaling along different types of processes or axes and the distinction between different types of scaling – deep, wide, out and up – is useful when it comes to illustrating what it involves.

Figure 6.2. Scaling deep, wide, out and up.

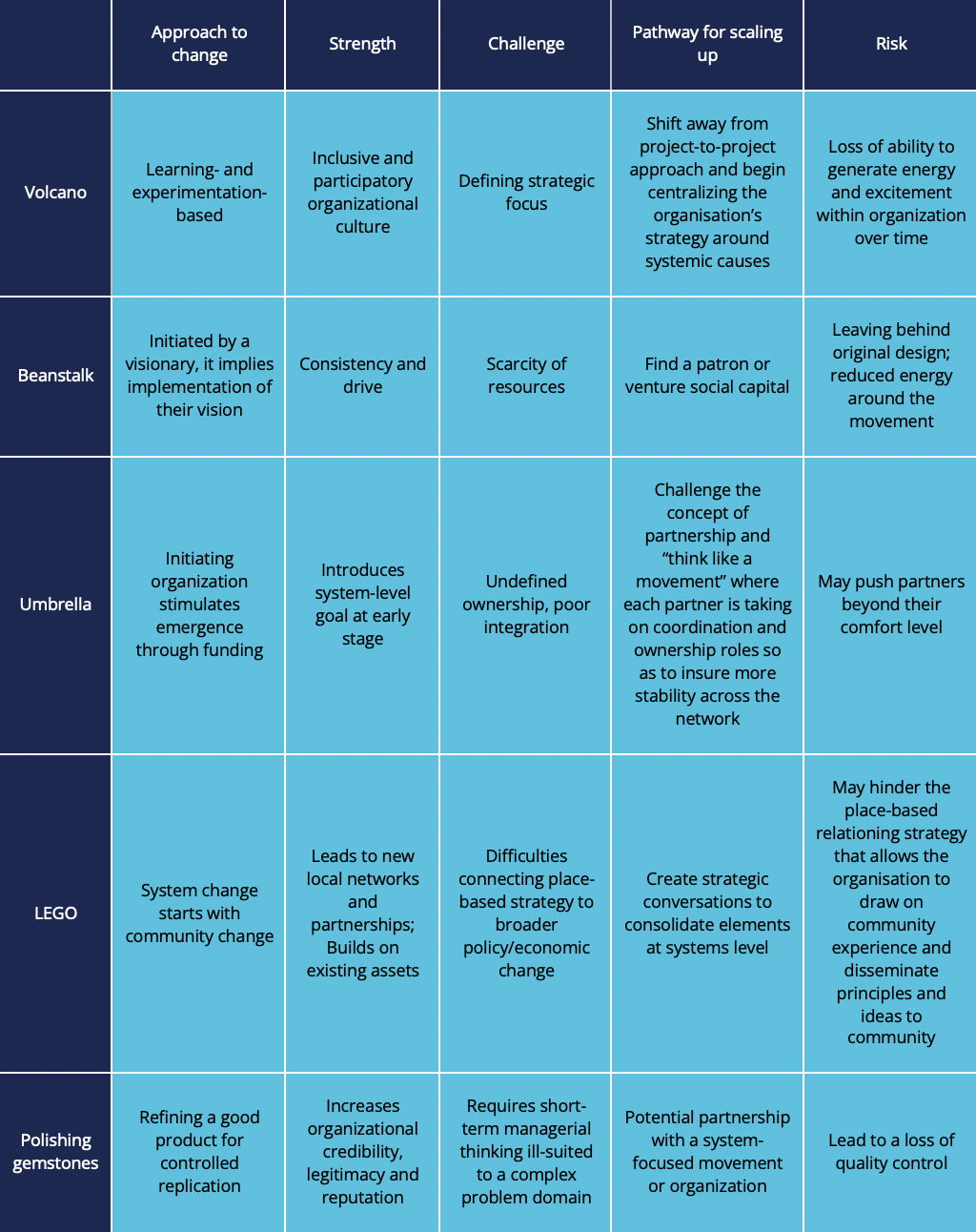

Another way to illustrate the complexity involved in the scaling of social innovation is to look at different the spread of social innovation in terms of structures or patterns. Frances Westley (et al. 2014) describe five such possible configurations. These configurations differ on a range of factors: their approach to change, strengths and challenges. They revolve around a different type of strategic pathways for scaling and come with distinct types of risks.’

Figure 6.3. Different Configurations for Scaling (from Westley et al. 2014).

For example, an “umbrella configuration” pathway might require the initiating organization to stimulate spreading through funding and/or it might involve creating a network of partners that “think like a movement”. The type of partnership involved might present some risk – pushing partners beyond their comfort level or lack of integration – but it arguably has the advantage of focusing on system-level goals from the beginning.

By contrast, a beanstalk configuration would typically be initiated by a champion garnering support from partners who can play the role of patrons or inject venture social capital. This configuration requires high levels of entrepreneurial motivation to get it started and push it along and is thus less demanding in terms of partnership building. But it may also suffer when resources available to the champion are scarce and there is always a risk that the original design and energy around the issue are left behind as new partners/investors come on.

For more, see F. Westley: Five Configurations for Scaling Up Social Innovation: Case Examples of Nonprofit Organizations From Canada in the Journal of Applied Behavioral Science (2014)

Case Study: The Birth Of The Registered Disability Savings Plan (RDSP)

Case Study: “From Total Innovation to Systems Change – The Case of the Registered Disability Savings Plan,”, F. Westley, N. Antadze, University of Waterloo.

Case Study media: Scaling PLAN: Interview with Al Etmanski

Case Study Notes

The RDSP case study highlights the critical role of systems enablers when it comes to working across systems to create change in political, cultural and economic systems. The RDSP is a Canada-wide registered matched savings plan specific for people with disabilities. What is involved in the creation of a new financial tool like an RDSP is more than the actions of a bank who would offer the product, but supportive legislation that secures matching contributions from government.

The case of RDSP offers a good illustration of what it means to recognise openings in the system and what managing emergence involves. It also shows how changing one part of a complex system can have influence on multiple, interconnected parts in unintended ways to create significant impact.

The founders of PLAN and initiators of RDSP, Al Etmanski and Vickie Cammack, are social entrepreneurs, community organizers and disability advocates. When they came up with the idea for the Registered Disability Savings Plan (RDSP), both had been advocating inside of their non-profit organizations for decades. Etmanski was the Executive Director of British Columbia’s Association of Community Living – a federation of organizations who advocates for the inclusion of people with developmental disabilities in different aspects of community life. Cammack was the founding Executive Director of the Family Support Institute – a province-wide organization that supports the families that have members with disability.

To address the systemic barriers to living a good life as a person with a disability, Etmanski and Cammack founded the Planned Lifetime Advocacy Network (PLAN). PLAN builds personal support networks around a person with a disability that help with life planning, school transitions, community involvement, financial objectives and more. These support networks were their first co-created project and it was very successful.

PLAN’s initial motivation was to strengthen circles of support around a person living with a disability and also provided companionship and solidarity for family members. The idea took off like wildfire. Demand increased quickly and Etmanski and Cammack were being drummed for advice, guidance, speaking engagements, media, visits across Canada and around the world. 40 organizations caught on to the idea of creating social networks like PLAN.

Despite PLAN’s success, Etmanski and Cammack decided to switch course to tackle the underlying structures of the issues people with disability face: inequity, poverty and loneliness. They knew that while parents are generally able to secure the social wellbeing of their children by strengthening their social networks, few manage to secure their financial future. At the time, fiscal policy provided no financial mechanisms to help families secure the long-term financial future of their children with disabilities. As a result, Etmanski and Cammack focused their efforts on developing a new financial mechanism to fill that gap. The idea was to look for a way to enable families to plan the financial future for their children.

Some policies have unintended negative consequences. Good intentions of government in providing welfare supports can prevent some individual to enjoying a full life, because they are guided by assumptions on what a person with a disability is capable of and what they can be trusted to be responsible for that are mistaken. These types of prejudice pose a risk in a number of other policy decisions involving marginalized peoples, e.g Indigenous services, unemployment, child welfare.

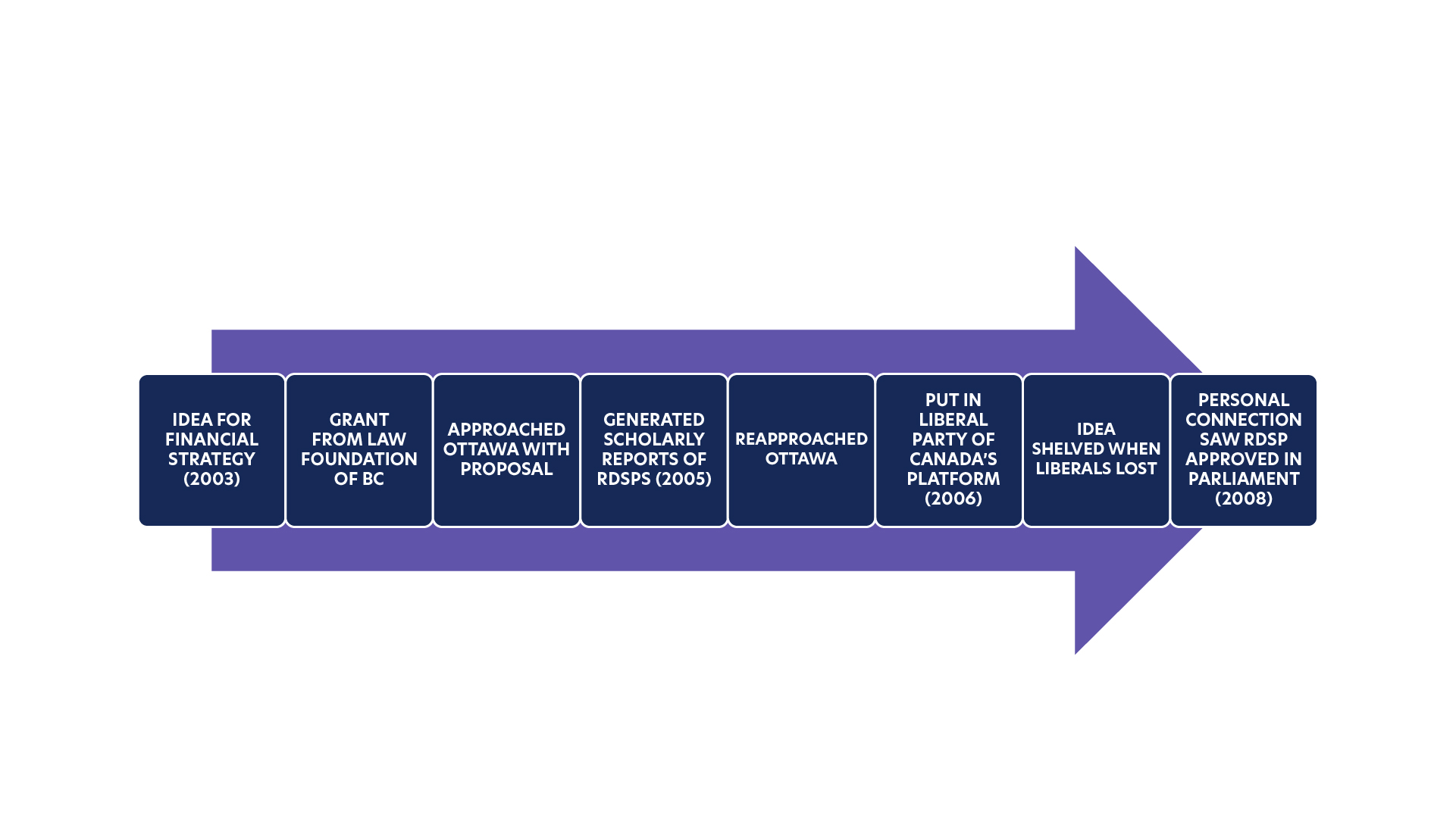

When it comes to systems challenges, there is no silver bullet. The barriers Etmanski and Cammack were facing were manifold. Some were institutional: complex tax laws created barriers for families trying to secure the future of their child with a disability, existing social assistance policy, lack of policy precedents and options for reform, concerns about the demographics of prospective beneficiaries of and contributors to a RDSP, concerns about the potential effectiveness of RDSP, concerns about the cost of implementation for government. But some barriers were the result of vagaries of political systems: Paul Martin who was leader of the Liberal Party of Canada at the time included the RDSP in the Liberals’ disability platform during the 2006 election. But the Liberal Party is defeated in the election.

Etmanski and Cammack’s story provides a good example of the type of unpredictability working for change in contexts of emergence requires. Despite the fact that RDSP had been a key policy point on the Liberals’ platform, the new Conservative Finance Minister Jim Flaherty eventually agreed to pursue it. Interestingly, Etmanski and Cammack’s relationship to Minister Flaherty was not a cynical tactic and neither was it political. It was the fruit of a connection that had been made several years before: both had a child with a disability. Once the new RDSP was approved by the legislature, the next step to gather the buy-in of the banks. Today all the banks offer the RDSP to their customers.

Figure 6.4. The RDSP Journey Timeline.

Etmanski and Cammack paid attention to and managed for emergence. This meant they could quickly pivot after the Liberals lost the election and regroup to approach different allies. Today Etmanski and Cammack continue their quest to change the belief systems and attitudes towards active citizenship.[1]

A system mediator:

- Has the capacity to shift their focus and engage with the system as a whole, not just one level or sector.

- Is aware and tolerant of the cyclical nature of innovation.

- Recognizes that achieving system-wide impact involves managing for emergence by paying careful attention to possibilities as they open across social, cultural, economic, and political landscapes, and nurturing resource and action networks.

In life, systems change never happens as a result of top-down, pre-conceived strategic plans, or through the mandate of any single individual or organisation. Change begins as local actions spring up simultaneously in many different areas. If these changes remain disconnected, nothing happens beyond what is happening locally. Connectivity is key to local actions’ capacity to cohere into a powerful system with influence at a more global or comprehensive level. This phenomenon is called emergence.

Emergent phenomenon:

- Exert more power than the sum of their parts.

- Have capacities different from those of the local actions that engendered them.

- Are often unexpected appearance.

The panarchy framework connects adaptive cycles in a nested hierarchy. There are potentially multiple connections between phases of the adaptive cycle at one level and phases at another level.

Slides

Partner Engagement

Activities and Assignments

References

- *Note: Unfortunately, some temporary legislative measures put in place for the RDSP are expiring in 2024, that negatively impact RDSPs in 2024. With these measures expiring, a person with a disability will be required to appoint a guardian (effectively giving up their legal status of personhood) in order to access their RDSP funds. This prevents people living with a disability from choosing to open an RDSP independently and those currently benefitting from the program to reconsider. This change goes against the fundamental motivations of what PLAN was working towards with the RDSP. To find out more, or how to get involved in preventing this change, visit RDSP Action Coalition of Ontario’s website. ↵