By the end of this unit, participants will be able to:

- Discern the level at which innovation has an impact.

- Articulate whether an innovation has altered lives, policies, beliefs and how.

- Recognize and be ready to take advantage of windows of opportunity to have a greater impact in a system.

Background

Unit 4 introduces the concept of ‘scaling’ as it is applied in systems change theory. It is common to think of scaling as what happens when an innovation or a product is commercialized successfully: it is disseminated and adopted en masse, the key being that as demand continues to increase, offer keeps up.

Because it is best understood through systems change theory and not standard business theory, social innovation cannot be modelled along the same lines. What scaling means cannot be reduced to the accounts offered by standard business theories and the law of supply and demand. In Unit 4, we explore what implementation and scaling mean for social innovation.

Unit 4 builds on Units 1-3 critically. It brings together what we learned about the social innovation spectrum, systems theory and the adaptive cycle to deepen our grasp of what scaling means in the context of social innovation. In Unit 4, we learn to identify the scale across which different types of innovation may happen. Not all innovation needs to scale and we will use examples to illustrate the notion that there are different “directions” of scale: up, out, or wide and deep.

Core Concepts

The Multi-Level Perspective

Just like the adaptive cycle, the multi-level perspective (MLP) on transitions is a way of articulating what change looks like across a system. While the adaptive cycle (Unit 3) is a model used to analyse the evolution of systems into its different phases (release, reorganization, exploitation, conservation), MLP articulate the structure of systems in terms of interactions between the various nesting elements of the larger system and explains how innovation scales or deploys across these multiple levels. Specifically, according to MLP, innovation scales as it moves across three levels: niches, regimes and landscape.

Illustration: The Organic Food Movement

The organic food movement was initially a niche innovation that managed to scale up through a system and to establish itself at the regime level.

In the beginning, during the first half of the 20st century, organic farming was a niche activity and those involved in organic farming operated at the margin of the regime. The regime, in that context, took the form of increasingly industrialized agriculture and included the use of synthetic nitrogen fertilizers and pesticides and depended on commercialization strategies that relied heavily on agricultural supply chains. In the 1960s-70s, organic farming gained momentum as the result of a wave of environmentalism at the level of the landscape that led to the introduction of the idea of sustainability.

The case of organic farming is interesting because it shows how a cultural shift can create an opportunity for an innovation at the niche level to scale up. As people began to be more attentive to the environment and sustainability became increasingly interested in what food they ate and how it was grown, organic farming and organic food began entering the mainstream: they started to transform organizations and institutions at the level of the regime. Supermarkets started offering organic food options to their customers as the norm.

Historians may point to the fact that the successful scaling of organic food as a social innovation resulted in pushback from those who, at the niche level, didn’t believe in mass market distribution and ownership of organic food. This in turn led to the development of new innovations – food boxes to homes and renewed interest in farmers markets in some regions.

This back and forth between niche and regime levels is a good thing, as it ensures that innovation constantly flows.

The MLP is helpful when it comes to identifying how social innovation emerges. The organic food movement is a good example of a social innovation “without a fixed address” that has scaled up and down and out from niche to landscape over time – ever-adapting. MLP illustrates how change happens over time, what conditions helped create the window of opportunity and what it might teach us as potential agents of innovation about how to prepare to introduce and scale a new initiative.

Types of Scaling

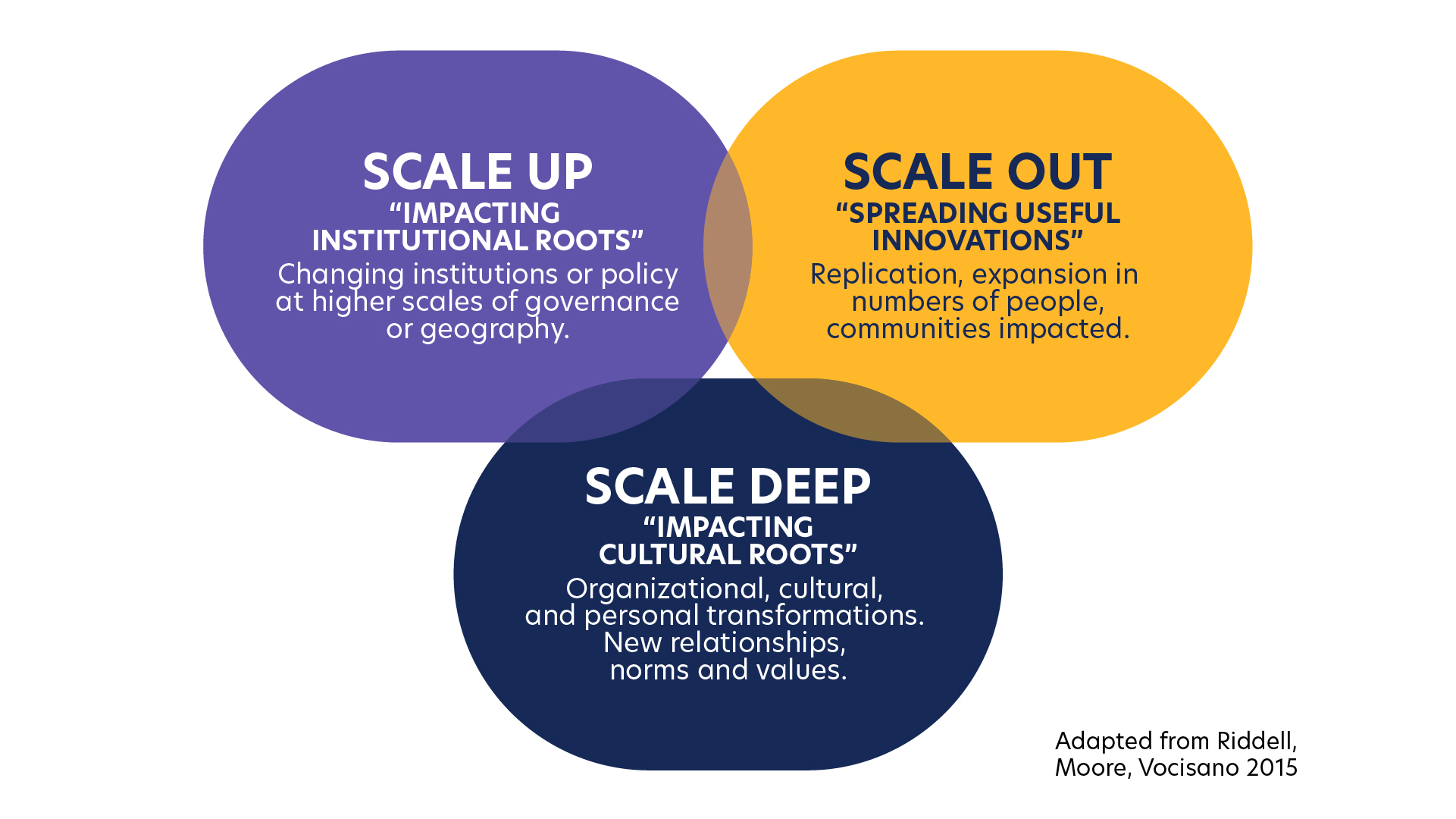

The process of scaling social innovations to achieve systemic impacts can be understood as involving three different types of scaling—scaling up, scaling out and scaling deep—and large systems change is likely to require a combination of these types.

Figure 4.1. Scaling Up, Out, and Deep.

Scaling Up

There are reasons to think that the success of a social innovation depends on whether it can be scaled up into the regime level: when an idea impacts our institutions, it gives rises to new ways of governing and regulations in education or health systems, etc. Social innovation can have a massive impact at the level of regime: widespread change to institutions is likely to impact people’s beliefs and culture and ultimately transform the landscape in which systems evolve.

Scaling up requires a good understanding of the landscape in which a social innovation is to be deployed, so as to identify opportunities and barriers at the institutional level and aim for system-wide change. When an idea impacts our institutions, it gives rises to new ways of governing (policy) that can in turn translate into change in the types of regulations we apply across entire domains. For instance, public health policy can lead to changes in fiscal policy in order to create new types of financial products (see the case of the Registered Disability Savings Plan below). More importantly, over time, widespread changes to institutions are likely to impact people’s beliefs and culture and ultimately transform the landscape in which the system evolves.

Scaling Out or Wide

To scale out innovation is to spread it to more users. This is the usual sense of “scaling”, as it is applied in business context. While the idea is generally the same, the process through which social innovation scales out is different. In the context of social innovation, typically, an idea cannot be adopted “en masse” without some significant iteration that allows the innovation to fit the specific context in which it is implemented. As a result, people sometimes talk of scaling wide.

The types of contexts in which ideas are developed and implemented to create social innovation vary a great deal. Because social innovation aims to impact people and their communities, it requires dedicated attention to their needs in the process of implementation. This explains why the scaling out of social innovation may require new types of business models or new forms of partnerships that place its specific users at the centre of implementation. To scale out an idea in a new community of users, one would need to be willing, for instance, to adapt and transfer insights and practices, setup organizational coalitions to address shared challenges, adopt procedures to facilitate knowledge exchange and adopt new ways to share accountability within the network.

Scaling Deep

The concept of scaling deep is helpful when it comes to understanding one specific aspect of the cultural change that takes place as a result of a social innovation: the process is both systemic and “place-based”.

Any attempt to replicate or implement a social innovation in a new context requires, for instance, not only that relevant stakeholders be identified but also that they be involved before attempts are made to implement the innovation. This, in turn, requires innovation actors to establish local relationships, understand contexts to develop customized programs and approaches, foster shared spaces, create common ground (alignment), strengthen existing relationships, absorbing and translating knowledge and practices.

Tips for Social Innovation Actors

Not everyone needs to come up with a new product or find a niche to innovate. This is an important point. Social innovation agents can occupy made different roles and parts. There is enormous potential for innovation agents who focus on finding ideas that already exist and support the process through which they are developed and scaled up, out, wide or deep.

Indeed, since scaling social innovation happens through different types of processes at different scales, there are also different roles innovation agents can play including those we considered in Unit 3: disruptive, bridging and receptive.

Those considering playing a role in social innovation might find the following tips useful:

Reflect deeply. There are multiple pathways for scaling, which may involve different types of resources and new ways of shaping and enabling demands (as opposed to merely meeting it)

Partner judiciously. The most powerful, dynamic scaling is cross-sectoral and requires connectivity across the system

Set a guiding purpose. In most cases, the ultimate goal is to prevent getting stuck and supporting the transformational process that leads to system change

Learn. All scaling modes and experiences generate valuable learning capable of informing system change.

Recognize the illusion of permanence. Social innovations do not have a fixed address, they evolve and migrate across the many levels of systems.

Be humble. We are in the earliest days of a concerted understanding of the cultural context and drivers of system change

The multi-level perspective (MLP) can be used to understand other aspects of change across a system. The MLP is useful to understand how change happens over time, what conditions help create windows of opportunity, and how actors in disruptive, bridging and receptive roles (see Unit 3) may be involved in scaling a new initiative.

The process of scaling social innovations to achieve systemic impacts is multifacetted. Systems change is likely to require a combination of scaling up, out/wide, and deep.

- Scaling up requires a good understanding of the landscape, to identify opportunities and barriers at the institutional level and aim for system-wide change.

- Scaling out/wide is the process of spreading an innovation to more users.

- Scaling deep requires attention to contexts and the specific place-based cultural change that need to place as a result of an innovation.

It is important to remember that:

- There is no “right scale” for an innovation – talk of scales and levels should be used to understand change and help build capacity for impact.

- There is no need to re-invent the wheel. Not everyone needs to be a niche innovator, and not every niche innovation needs to be an invention. There is enormous potential in identifying niche innovation that already exist scale them up.

Slides

Partner Engagement

Activities and Assignments