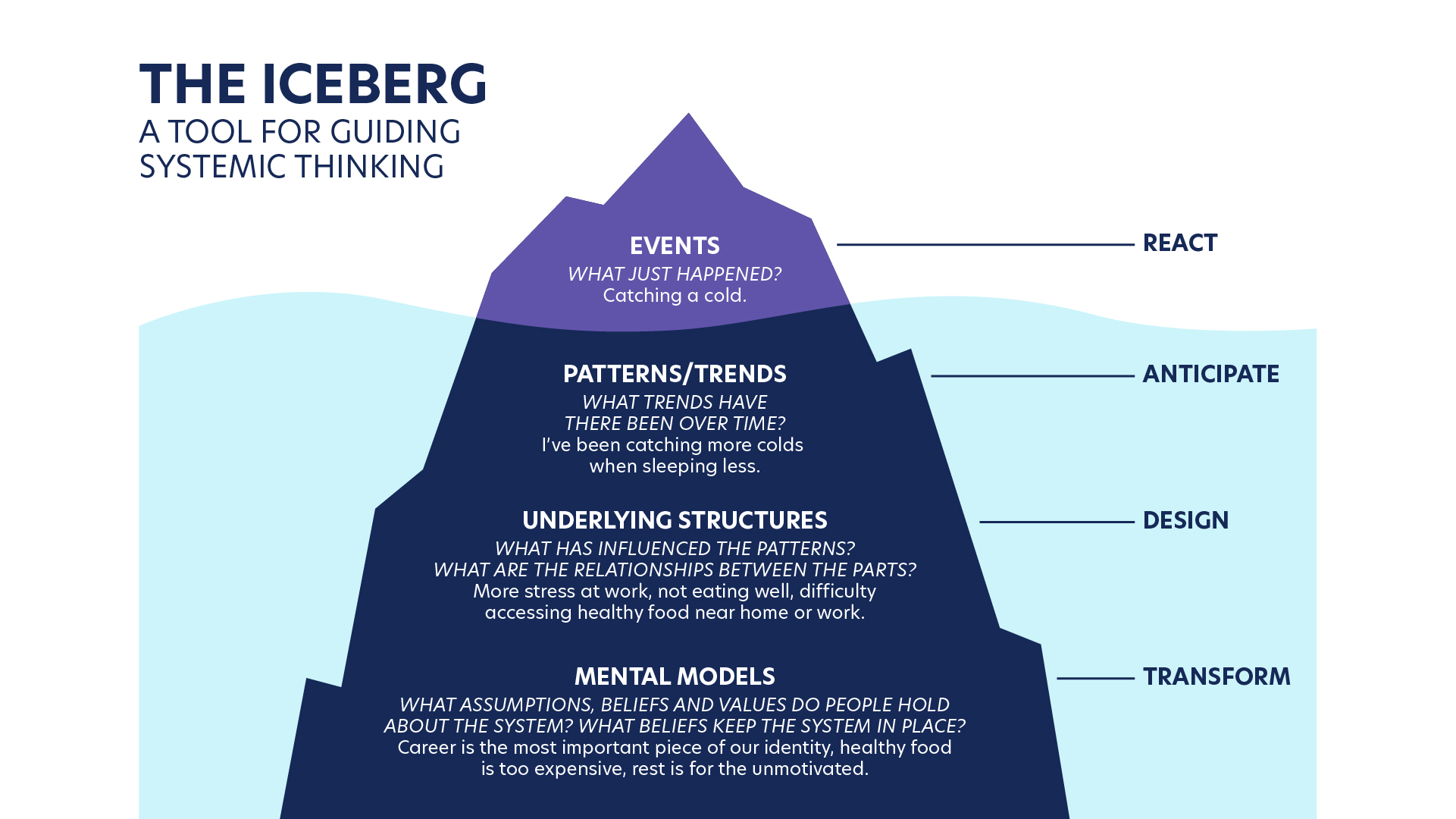

The Iceberg Model

The nesting metaphor is designed to emphasize the fact that the structures that underpin systems is multilayered. But when it comes to analysing an issue from a systems perspective, other metaphors can also be useful. For instance, we can also think of systems as icebergs.

Figure 2.3. An Iceberg Model.

We know that roughly only 10 percent of an iceberg’s total mass is above the water line for us to see. The rest is underwater, invisible to the observers from the surface. However, that 90 percent is what the ocean currents act on and what creates the iceberg’s behaviour at its tip. Global issues and wicked problems can be viewed in this same way (ecochallenge.org).

What happens above the surface in our human systems are events. We live in an event-oriented world and our language reflects that. What we see and experience is underpinned by the systems and it is from these systems that events emerge. Events are what happens above the surface, but they are rooted in patterns and systemic structures that exist below. In other terms, events are co-determined by patterns and trends, which are so to say their accumulated memory. These patterns and trends are themselves the effects of systemic structures that define how the system is organized. To make sense of this complexity, it is useful to think of systemic structures as:

- Comprised of parts or components.

- Contingent on a history.

- Depending on beliefs, behaviours and assumptions of systems actors.

Dancing with Systems

Because they are complex, systems do not generally respond to the way we would like to our efforts to change them. As systems theorist Donella Meadows explains, it is easy to be overconfident in our ability to change the world and to inadvertently exaggerate the significance of the impact we expect to create.

For those who stake their identity on the role of omniscient conqueror, the uncertainty exposed by systems thinking is hard to take. If you can’t understand, predict and control, what is there to do? […] Systems can’t be controlled, but they can be designed and redesigned. […] We can listen to what the system tells us and discover how its properties and our values can work together to bring forth something much better than could ever be produced by our will alone.

– Donella Meadows

Systems thinking calls for responsiveness and flexibility. According to Meadows, “systems wisdom” can be broken down in 14 points:

- Get the beat: learn about the system before you disturb it.

- Listen to the wisdom of the system: before you try and make things better, pay attention to the value of what’s already there.

- Expose your mental models to the open air: share what you know/think with others to challenge assumptions

- Stay humble. Stay a learner: admitting mistakes and learning from them

- Honour and protect information: do not distort, delay, or sequester information; you can make system work better if you can give it more timely, more accurate, more complete information.

- Locate responsibility in the system: look for ways the system creates its own behaviour through feedback about the consequences of decision-making

- Make feedback policies for feedback systems: policies that design learning into the management process.

- Pay attention to what is important, not just what is quantifiable: you can’t precisely measure justice, democracy, security, freedom etc. But they are important.

- Go for the good of the whole: don’t maximize parts of systems or subsystems while ignoring the whole.

- Expand time horizons: the longer the operant time horizon, the better the chances for survival.

- Expand thought horizons: follow a system wherever it leads and it will require more than being “interdisciplinary”.

- Expand the boundary of caring: the real system is interconnected; no part of the human race is separate either from other human beings or from the global ecosystem.

- Celebrate complexity: the world is complex.

- Hold fast to the goal of goodness: don’t weigh the bad news more heavily than the good and keep standards absolute.

Humility (#4) is crucial to recognizing that humans can’t impose their will on a system. Humility, however, does not affect the capacity of changemakers to tackle wicked issues. There is plenty to observe, to learn, to test and create. As Meadows puts it, while you may not be able to control a system, you can dance with it!

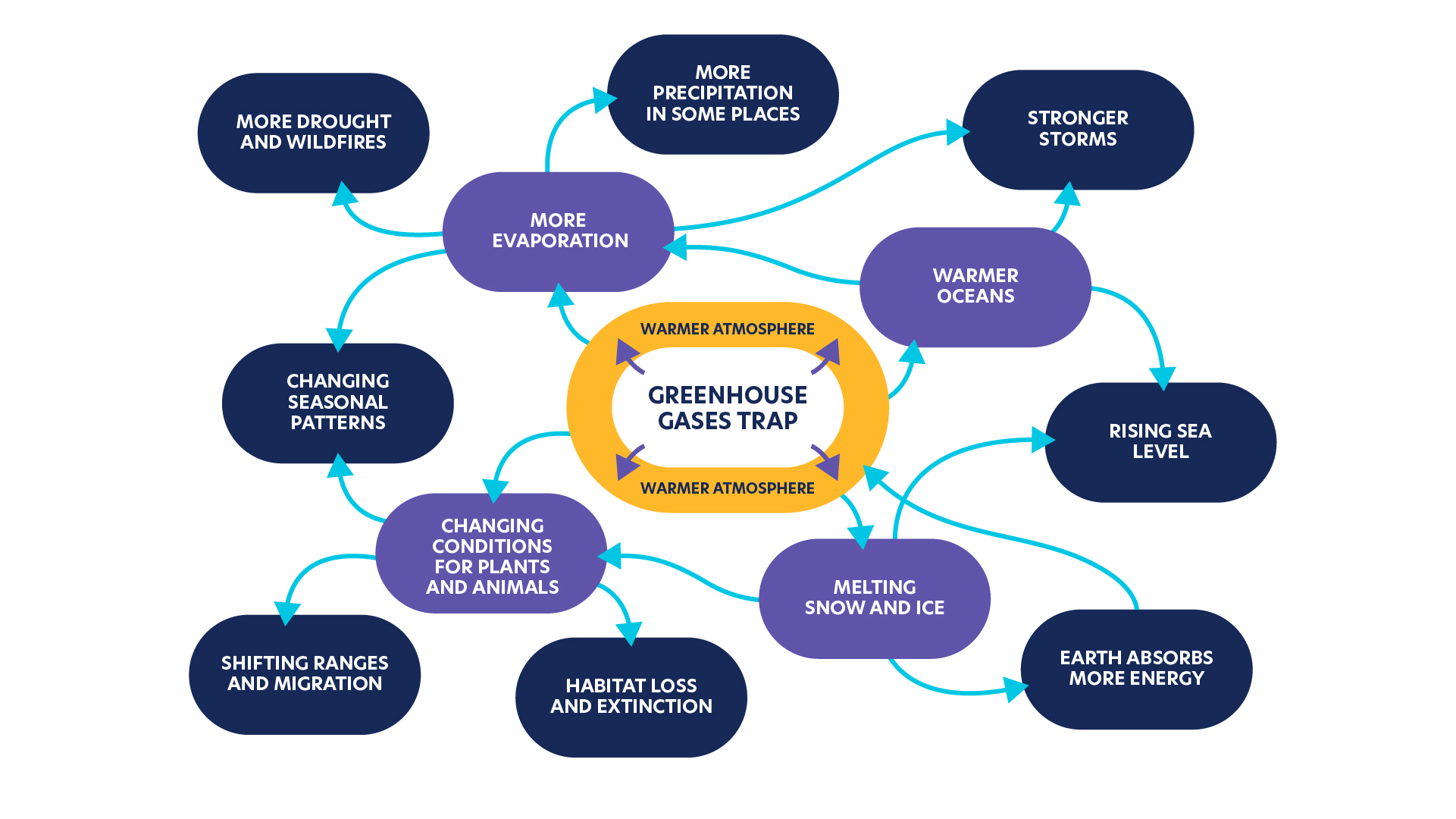

Systems Mapping

A systems map is a snapshot of a system and its environment at a given time.

We know that a system is defined by its purpose. The purpose of a system determines its general boundaries. From this perspective, there is a wide range of types of entities that can be understood as systems: organizations, activities (like hockey games), people, the assets around which a project is organized, etc. For example: A community foundation or a UnitedWay is an organization that can also be described as a system of people, assets, stakeholders, relationships, resources etc. Likewise, an initiative like “Run for the Cure,” can be described as a system that includes people (fundraisers, staff, runners, beneficiaries) activities (fundraising, training, running, donating) as well as other elements, each of which may have parts or relations

A systems map shows how the elements of a system might be grouped together as components parts and sub-parts and also shed light on the relationships between them.

Strictly speaking, a system may have several different maps, none of which stand to be “the right one”. Systems maps are a representation of our individual and/or collective understanding of the system: they are instruments we use to visualize interactions, patterns, assumptions and areas of potential collaborative action.

Figure 2.4. Exemplar of a Systems Map.

Understanding Systems Theory

Systems thinking is:

- A way of looking at how the world works, in its complexity, at multiple scales and from multiple vantage points, with many connections and interdependencies in play where component parts cannot be separated from the whole.

- The boundaries of a system are not fixed.

- Where we set the boundaries changes how we see and understand the system.

- Systems thinking is important because understanding how systems work, and how we play a role in them allows us to function more effectively and proactively within them (paraphrased quote by Daniel Lim, organizational consultant).

A system is any group of interacting, interrelated or interdependent parts that form a complex and unified whole that has a specific purpose. Without the interdependence, we would just have a collection of parts – not a system. Humans try to control systems, but we are often reminded that we must work with them. Systems are also nested, with smaller systems existing within larger systems, and experience interactivity.

Complexity science is not a single theory, but the study of complex adaptive systems and the patterns of relationships within them, how they are sustained, how they self-organize and how outcomes emerge.

Brenda Zimmerman described problems as simple, complicated, or complex. A simple problem, such as baking a cake, does not require particular experience so long as one can follow instructions. A complicated problem, such as sending a rocket to the moon, requires expertise, but with the right people and resources there is a good chance of success. Raising a child is an example of a complex problem because of how even with research etc. there are few guarantees it will go smoothly, and past experience does not guarantee repeated success given the numerous factors outside one’s control; one must do their best, stay adaptive and find a way forward. Social innovation applies to complex problems.

Engaging with Systems Theory

One way of seeing systems is to use the metaphor of the iceberg: https://ecochallenge.org/iceberg-model/. This activity allows us to see what are day to day events, what are patterns, and what are systemic structures of how the system is organized.

Systems theorist Donella Meadows describes realizing that she could not control or predict systems, but she could “dance with them.” https://donellameadows.org/archives/dancing-with-systems/

Systems mapping is the activity of making a snapshot of a system and its environment at a given time. A systems map shows how the elements might be grouped together as components of the specified system of interest. The map represents an individual or collective understanding to visualize interactions, patterns, assumptions, and areas of potential collaborative action.