By the end of this unit, participants will be able to:

- Appreciate what social innovation means for the purpose of this course.

- Distinguish between adaptation and transformation in innovation contexts.

- Explain the difference between invention and innovation.

- Identify the micro-, meso- and macroscopic levels of the social innovation spectrum.

Background

What should one know to be able to recognise and apply the basic principles of social innovation and work toward addressing wicked social problems and global societal challenges?

Unit 1 introduces the concept of social innovation, stressing a series of distinctions between e.g., adaptation and transformation, invention and innovation that will subsequently inform future lessons.

The definitions used here build on proposals by experts and practitioners who work on social innovation, resilience and complexity (such as Dr. Frances Westley and Dr. Brenda Zimmerman, who were involved in launching Social Innovation Generation in the first decades of the 2000s) and more recently, by research The/La Collaborative and Social Innovation Canada have conduced collaboratively.

An apt concept social innovation needs to be broad enough to include everything that can be assumed to belong to social innovation, but specific enough to exclude activities and approaches that do not.

A definition of social innovation such as, for example: “Social Innovation is about new ideas that can meet pressing unmet needs” is too broad. This is because social innovation is not only defined by its purpose, but by the type of issues it address. As we understand social innovation, these issues revolve around “complex” problems and call for changes that is “systemic”. What is distinctive in social innovation as we understand it is precisely the fact that it aims at transforming systems that are social in essence and thus multifaceted and dynamic.

In Unit 1, we tackle these definitional issues, focusing on three important distinctions:

- The distinction between adaptive innovation, i.e. innovation processes that aim at improving a situation and transformative innovation, i.e. innovation processes that lead to structural or radical change.

- The distinction between innovation and invention.

- The distinction between the micro-meso and macroscopic levels of the social innovation spectrum.

Core Concepts

Social Innovation

Watch the video, “What is Social Innovation?” by Social innovation Generation (SiG) Canada

Social innovation is an initiative, product, process or program that profoundly changes any social system by changing one or more of:

The basic routines (how we act; what we do)

The resources flows (money, knowledge, people)

The authority flows (laws, policies, rules)

The beliefs (what we believe is true, right/wrong)

Successful social innovations reduce vulnerability and enhance resilience. They have durability, scale and transformative impact.

– Frances Westley

Consider the definition of social innovation we propose above. Compared to definitions of social innovation that are broader, e.g. “social innovation is any new method, idea, product, etc… for the social good”, the one we favour may feel clunky and wordy. Some have even argued that definitions such as the one we adopt and others that are equivalent, are unnecessarily complicated and/or that they exclude a range of initiatives that should count as social innovation.

But are these criticisms justified? Is there a simpler definition of social innovation that could appeal to critics and would be simpler?

It’s always important to be critical of new concepts when they are introduced. But it is also important to engineer concepts that can do the work we need them to do. A good definition of social innovation would be one that succeeds in making clear what would count as a contribution to the type of change we’re aiming for, i.e. what it means to effect systemic change. To tackle wicked social issues and global challenges, we need to adopt approaches to innovation that are designed to transform complex systems. Hence, we need a definition of social innovation that reflect this desideratum and thus signal that the aim is to radically impact and reshape the systems that are the source of these problems in the first place.

For more on the topic of definition see “The SiG Story: The Power of a Definition” (Social Innovation Generation, p.30).

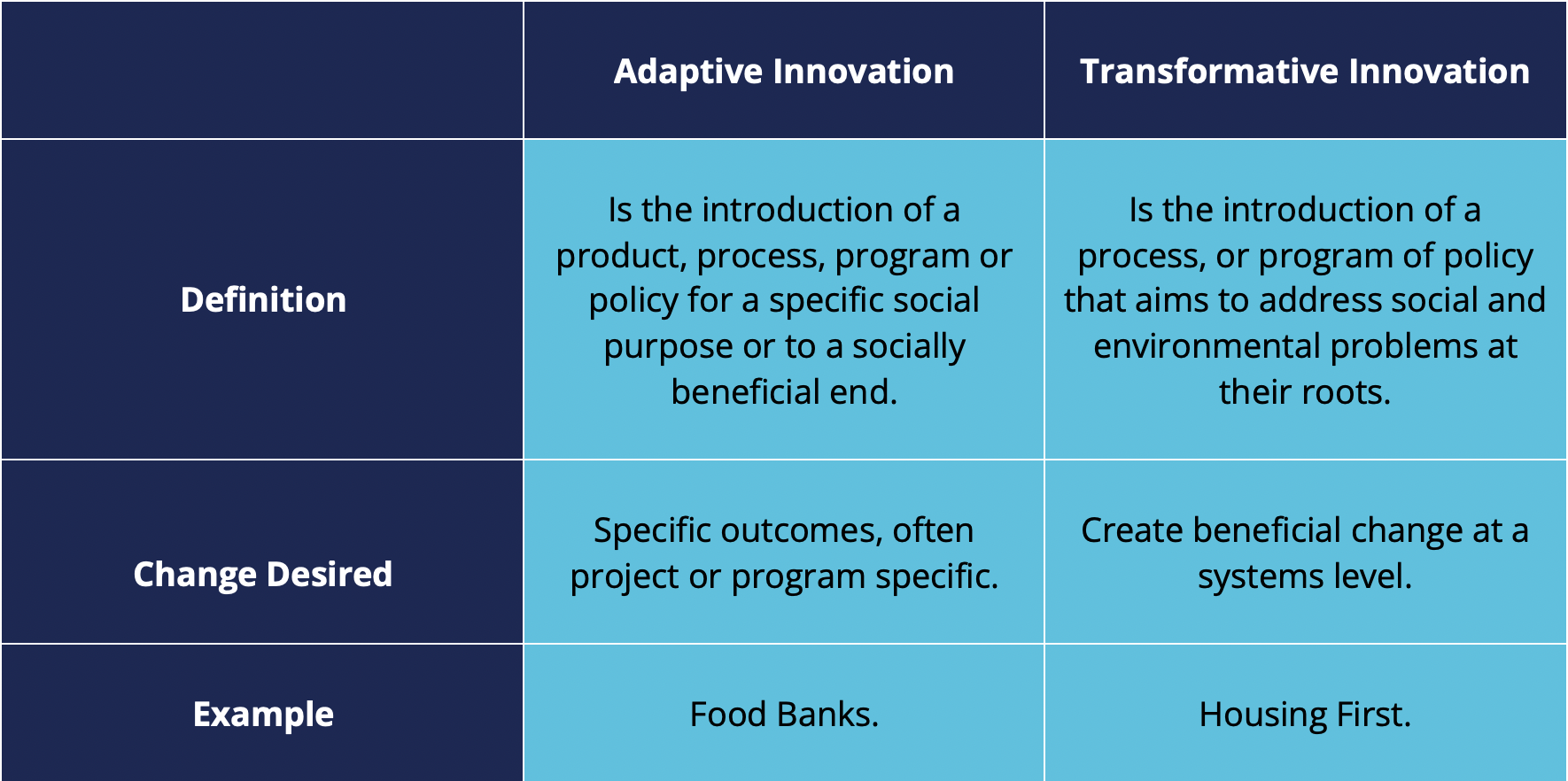

Adaptation vs. Transformation

The definition of social innovation we use implies that to engage in the field is to attempt to address complex problems at their root causes through activities that target positive social and environmental change. Importantly, social innovation is a process that needs to be understood as happening in complex, nested systems or, as some other have put it, across broader ecosystems.

In our societies and in the non-profit sector in particular, many organizations have a social purpose: they exist to alleviate the worst impacts of systemic problems, such as homelessness or hunger. Social purpose organisations work primarily to improve the human and social conditions in the systems in which they operate. They operate at the frontline, to help people adapt to change in the world while being part of it. But social purpose organisations often don’t have the capacity to address the root causes of these problems. Social purpose organisation and community nonprofits need innovation and in many cases, they need innovation to address immediate and urgent needs of our communities.

This raises the following question:

Is the purpose of social innovation to provide solutions to specific problems in the social space by creating or improving e.g. a products, programs or processes offered through social purpose organisations or does social innovation aim at systems level change to transform institutions, social relations and power structures to improve well-being in our society?

The answer is undoubtedly something like: “We should not have to choose, because we need both.” The better way to frame the question is to ask:

What is the difference between “adaptive” and “transformative” social innovation?

Adaptive innovation focuses on the potential of innovation for solving, often piecemeal, specific problems that social purpose organisations face. For example, a product or program developed by a non-profit and aimed at solving social problems would satisfy the adaptive definition. Adaptive innovation is chiefly concerned with increasing positive outcomes and the necessity of addressing unmet needs by creating products, programs and services that help people adapt to the problem.

What is distinctive of transformative approaches to social innovation, by contrast, is that it attempts to provide solutions to wicked societal challenges: the solutions that come out of transformative social innovation target the systemic conditions in which complex, wicked societal and environmental issues arise. It aims at transforming the social institutions, at a systems level, to address the problems at their roots. This requires a deep knowledge of the environment – i.e. of the ecosystems in which the issues are embedded – and unavoidably draws on high levels of collaboration. Transformative innovation predominantly tackles social problems at the root, which requires changing social relations, rebalancing the distribution of power and, ultimately, transforming the fabric of social institutions.

The distinction between adaptive and transformative innovation is important: Both are critical because both reduce harm and increase resilience in our communities, but they do so through very different processes. (see Unit 3).

Figure 1.1. Adaptative vs Transformative Innovation.

Adaptive social innovation is the introduction of a product, process, program or policy for a specific social purpose or to a socially beneficial end. The change desired in adaptive context will be measured in terms of specific outcomes.

Transformative social innovation (or social systems innovation) is the introduction of a process, or program of policy that aims to address social and environmental problems at their roots and create beneficial change at a systems level. Because change at the systems level is difficult to assess and measure, understanding systemic transformation requires bespoke conceptual tools, the fundamentals of which are introduced over the next units.

The aim of transformative social innovation is to reduce human and environmental vulnerability. This takes time. It requires that we reallocate resources upstream to the source of problems to transform the system and build the resilience of a new normal. But the impacts of systemic problems are immediate and affect people now. In that context, proposing adaptive solutions as we work to change current systems or contribute to the building of a new way of operating can play an important role. Adaptation is thus also important and necessary; because systems level change can take time and there needs to be effort at improving products, programs and services that aim to provide value in the current system, to alleviate or address urgent needs.

Brief Case Studies

Below are three case studies to distinguish the difference between adaptative and transformative social innovation.

Figures 1.2. Housing First and 1.3. Food Bank.

Invention vs Innovation

Invention is defined as the creation of a product or the introduction of a process, for the first time. Once something as been invented, it can continue to be improved. A product will typically change over time without stopping to be that specific product (think of the many different models of the iPhone!) in which case we will talk of different versions. Once a process has been invented, it can likewise go through an indefinite number of iterations.

Innovation is different from invention, versioning and iteration. In fact, some inventions may fail to lead to innovation – just think of the myriads of patents that have never been commercialised or otherwise used to create positive change.

One way to understand the difference between innovation and invention is to think of innovation as a process designed, not to contrive something new, but to create change. Creating change does not always require invention. It is in this sense that innovation is best understood as a process – as opposed to a finality or product – through which fresh concepts or approaches are introduced, or through which existing ideas or approaches are used or implemented to create real-world utility.

The operating concepts here are “utility” and “change”: Innovation happens when people use an idea or approach to create change.

Illustrations

Figure 1.4. Tupperware Party and 1.5. Public Library.

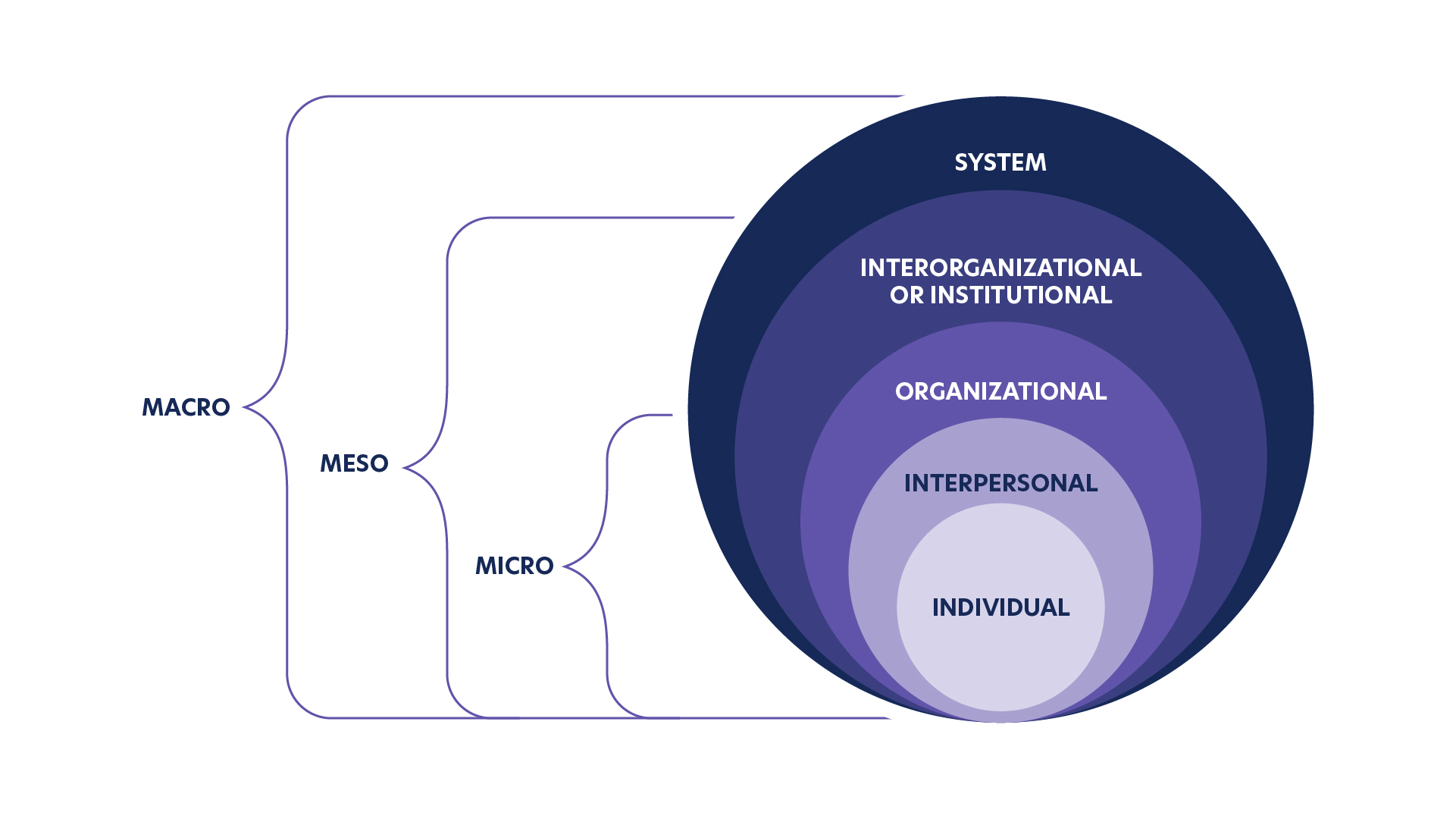

Individuals, Organizations and Systems

Social innovation can be driven or born by different types of social actors at the same time and, as we will see below, it happens on a spectrum. The notion that scaling can happen because of individual, interpersonal, organisational, interorganizational and systems activity is useful when it comes to making sense of the fact that social innovation is a multilayered process whose home ground is complexity. It also serves to stress another important point: “lone innovators” on their own cannot create the sort of change needed to address wicked social issues.

Implementation at the Micro-, Meso- and Macroscopic Levels

Figure 1.6. Micro-, Meso- and Macro Levels.

Individual and Interpersonal Level

At an individual level, change can be driven by “social entrepreneurs”, for instance, who generate ideas, test them out and encourage others to get behind them to work innovation into the interpersonal realm and build momentum. Typically, we talk of social entrepreneurship to refer to individual social innovation efforts.

Organizational Level

To come into play at the organisational level, an idea must be formalised and operationalised. This will typically take the form of an initiative or project within an organization. Some projects and enterprise may grow into or be designed to draw on more complicated interorganizational structures, which can in turn increase the potential for impact.

Interorganizational, Institutional and Towards the Ecosystemic Level

Ideas that are designed to generate impact across complex human and institutional contexts and to scale up and out to transform a nexus of relations are properly “systems-level” and they fall under the jurisdiction of transformative social innovation processes.

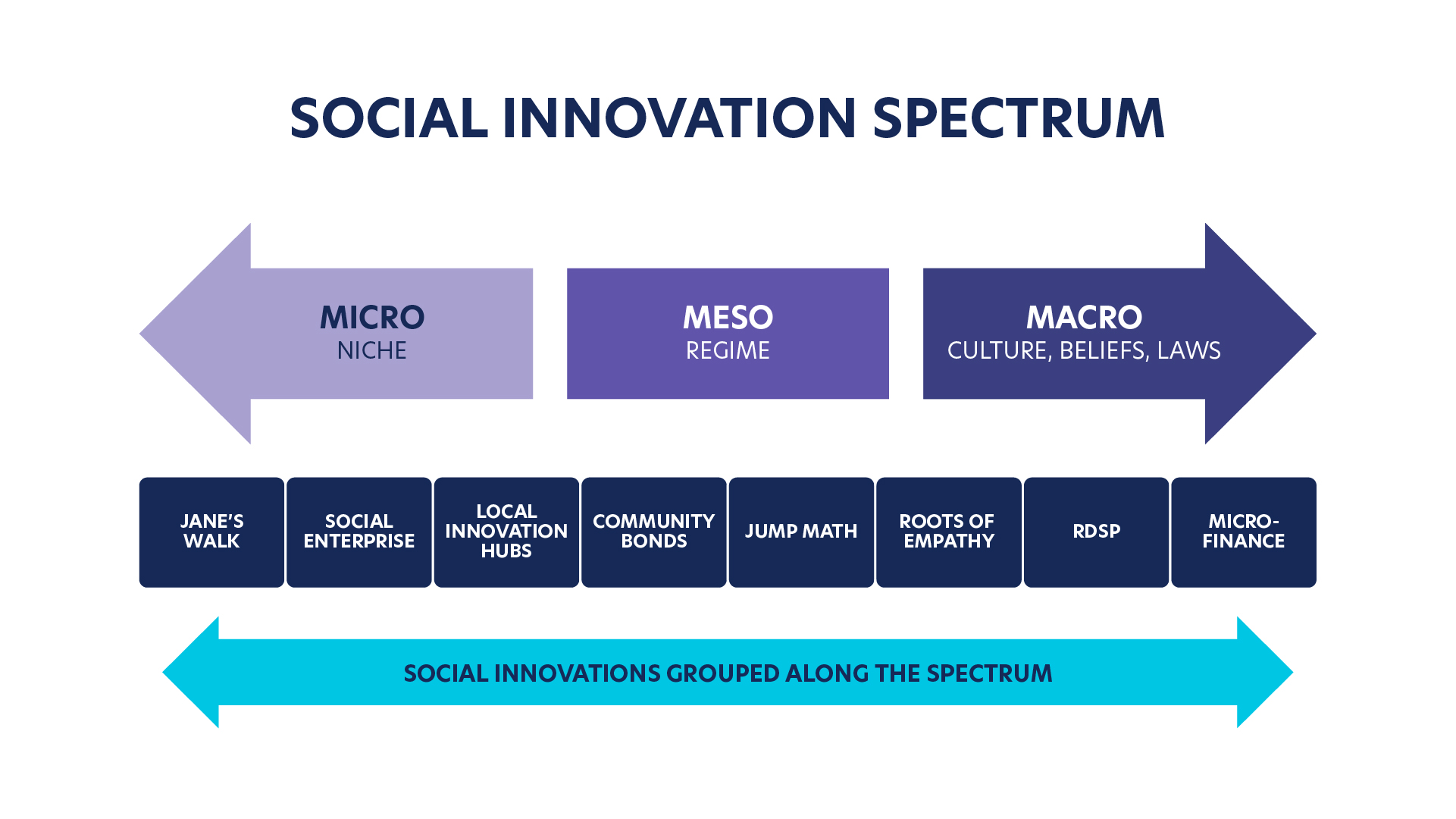

Social Innovation Spectrum

Social innovations can be implemented across different levels of social reality and there are important differences between the ways in which adaptive and transformative innovation can be implemented at each level. As we will see in Unit 4, in the context of social innovation, scaling not only happens across different levels, but it also happens along different axes: social innovation can scale out, but more importantly it can scale up, down and deep.

The change brought about by social innovation may happen at different levels in a system and successful social innovations are usually those that are designed and calibrated to have impact at the level intended.

Likewise, social innovation may have “cascading effects”: changes at one level may create change at other levels over time. This is where huge transformative potential and the risks associated with unintended consequences of social innovation both reside. When the cascading effects of an innovation are negative, we can speak of “cascading failures”.

Figure 1.7. Social Innovation Spectrum.

Social innovation is an initiative, product, process or program that profoundly changes any social system by changing one or more of:

- The basic routines (how we act; what we do)

- The resources flows (money, knowledge, people)

- The authority flows (laws, policies, rules)

- The beliefs (what we believe is true, right/wrong)

Successful social innovations reduce vulnerability and enhance resilience. They have durability, scale and transformative impact.

There is a difference between adaptation and transformation. Adaptation is a form of improvement and happen when we aim to tweak or streamline existing conditions in the systems in which we operate. Adaptation is involved in alleviating the worst impacts of our systemic problems like homelessness or hunger, but it is remedial and/or corrective. Some form of innovation may be involved in adaptation. By contrast, transformation or transformative social innovation seeks to change the very systems in which societal issues emerge. Both approaches are important and needed.

The distinction between invention and innovation is also central. We talk of an invention when a product or process is created for the first time. Innovation is about change and utility: Innovation happens when people use an idea or approach to create change. Creating change does not always require a new idea or product. Most of the time it does not.

Innovation is best understood as a process through which fresh concepts or approaches are introduced, or through which existing ideas or approaches are implemented so as to create real-world utility. Social innovation does not require invention, but ultimately, it requires the purpose to addressing social issues, or challenges at its roots, i.e. at the level of the system.

Social innovations can have outcomes at the micro, meso and macro levels. At the micro-level, social innovation is carried out by individuals, in which case it happens on a small scale and may serve niche interests and needs. At the meso-level, innovation is implemented in organisations, affecting their structures, including routines, regime and networks. At the macro-level, innovation transforms aspects of societies, including institutions, culture, beliefs and policies. Recognising at what level innovations happen on the spectrum is useful when thinking about the way in which it can scale up, down, or out (more on this in Unit 4).

Slides

Partner Engagement

Students will benefit from community partners’ engagement in discussion, such as small group discussion to enrich the learning in the classroom. Community partners should be warmly encouraged to share the knowledge they have of the context in which social innovation may or may not be happening in and around their organizations.

Suggested outline: In small groups, we invite community partners and students to:

Figure 1.8. Small Group Discussion.