To work at our best to deliver positive social impact, it is useful to build a solid foundation, and this starts with mastering the core concepts at play . It may sound obvious, but before we can change a situation, we have to better understand the situation. Having an impact on social issues, especially “wicked” ones. is difficult no matter how experienced one is; so equipping yourself with the right conceptual tools is critical.

Unit 1: Introduction to Social Innovation

Social innovation is an initiative, product, process or program that profoundly changes any social system by changing one or more of:

- The basic routines (how we act; what we do)

- The resources flows (money, knowledge, people)

- The authority flows (laws, policies, rules)

- The beliefs (what we believe is true, right/wrong)

Successful social innovations reduce vulnerability and enhance resilience.

They have durability, scale and transformative impact.

– Frances Westley

There is a difference between adaptation and transformation.

Adaptation is a form of improvement and happen when we aim to tweak or streamline existing conditions in the systems in which we operate. Adaptation is involved in alleviating the worst impacts of our systemic problems like homelessness or hunger, but it is remedial and/or corrective. Some form of innovation may be involved in adaptation.

By contrast, transformation or transformative social innovation seeks to change the very systems in which societal issues emerge. Both approaches are important and needed.

The distinction between invention and innovation is also central. We talk of an invention when a product or process is created for the first time. Innovation is about change and utility: Innovation happens when people use an idea or approach to create change. Creating change does not always require a new idea or product. Most of the time it does not.

Innovation is best understood as a process through which fresh concepts or approaches are introduced, or through which existing ideas or approaches are implemented so as to create real-world utility.

Social innovation does not require invention, but ultimately, it requires the purpose to addressing social issues, or challenges at its roots, i.e. at the level of the system.

Social innovations can have outcomes at the micro, meso and macro levels. At the micro-level, social innovation is carried out by individuals, in which case it happens on a small scale and may serve niche interests and needs. At the meso-level, innovation is implemented in organisations, affecting their structures, including routines, regime and networks. At the macro-level, innovation transforms aspects of societies, including institutions, culture, beliefs and policies. Recognising at what level innovations happen on the spectrum is useful when thinking about the way in which it can scale up, down, or out (more on this in Unit 4).

Helpful Resources

- “Primer on Social Innovation A Compendium of Definitions Developed by Organizations Around the World,” G. Cahill, The Philanthropist, October 2010

Unit 2: Introduction to Systems

Understanding Systems Theory

Systems thinking is:

- A way of looking at how the world works, in its complexity, at multiple scales and from multiple vantage points, with many connections and interdependencies in play where component parts cannot be separated from the whole.

- The boundaries of a system are not fixed.

- Where we set the boundaries changes how we see and understand the system.

Systems thinking is important because understanding how systems work, and how we play a role in them allows us to function more effectively and proactively within them (paraphrased quote by Daniel Lim, organizational consultant).

A system is any group of interacting, interrelated or interdependent parts that form a complex and unified whole that has a specific purpose. Without the interdependence, we would just have a collection of parts – not a system. Humans try to control systems, but we are often reminded that we must work with them. Systems are also nested, with smaller systems existing within larger systems, and experience interactivity.

Complexity science is not a single theory, but the study of complex adaptive systems and the patterns of relationships within them, how they are sustained, how they self-organize and how outcomes emerge.

Brenda Zimmerman described problems as simple, complicated, or complex. A simple problem, such as baking a cake, does not require particular experience so long as one can follow instructions. A complicated problem, such as sending a rocket to the moon, requires expertise, but with the right people and resources there is a good chance of success. Raising a child is an example of a complex problem because of how even with research etc. there are few guarantees it will go smoothly, and past experience does not guarantee repeated success given the numerous factors outside one’s control; one must do their best, stay adaptive and find a way forward. Social innovation applies to complex problems.

Engaging with Systems Theory

One way of seeing systems is to use the metaphor of the iceberg: https://ecochallenge.org/iceberg-model/. This activity allows us to see what are day to day events, what are patterns, and what are systemic structures of how the system is organized.

Systems theorist Donella Meadows describes realizing that she could not control or predict systems, but she could “dance with them.”

https://donellameadows.org/archives/dancing-with-systems/

Systems mapping is the activity of making a snapshot of a system and its environment at a given time. A systems map shows how the elements might be grouped together as components of the specified system of interest. The map represents an individual or collective understanding to visualize interactions, patterns, assumptions, and areas of potential collaborative action.

Helpful Resources

- “How the Supply Chain Broke and Why it won’t be fixed anytime soon,” Peter S. Goodman, NY Times, October 22, 2021, Peter S. Goodman, NY Times, October 22, 2021

Unit 3: The Adaptive Cycle

Resilience is the capacity of a system to absorb disturbance and reorganize while undergoing change. It is neither about persistence nor change on their own, but about balancing and integrating both into an adaptive cycle.

Adaptability is the capacity of individuals within the system to maintain or manage its resilience through continuous invention and adjustments. Adaptability requires the capacity to understand when and where an actor finds themself in the system and how they can prepare, lead or implement the change needed.

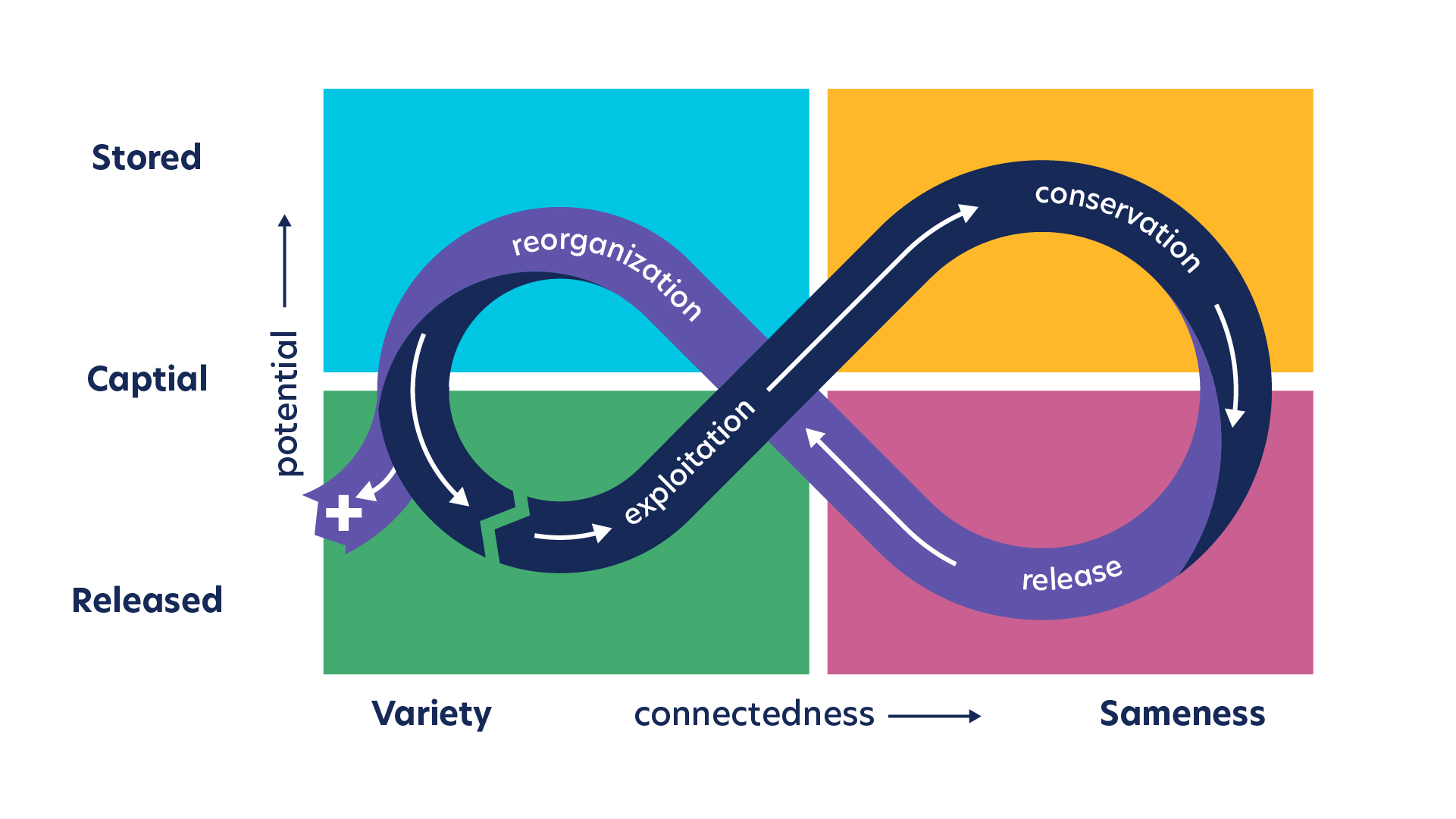

The Adaptive Cycle illustrates the flow of energy and resources over the course of a system’s evolution

- Release an idea is born, a new beginning that often comes with a breakdown of networks and meanings, and requires letting go of what is familiar.

- Reorganization/Exploration the idea is developed, this often requires a great deal of experimentation which may lead to initiatives whose outcomes may be difficult to assess and where return on investment is not immediately tangible.

- Exploitation the idea is launched as a product, process, organization or something else. Demand for delivery and productivity emerge, increasing the need for organizing.

- Conservation the idea has “established” and the innovation is adopted. This is the time to manage aptly, measure returns and performance, and focus on reliability and productivity.

Figure 3.1. The Adaptive Cycle of Systems.

The Adaptive Cycle isn’t always completed from start to finish. At various stages, it can “get stuck”, and the cycle adjusts back to its previous point. To move past the issue, it is useful to keep an eye for some of the better known issues or trap system will encounter in transition from one phase to another.

- Rigidity trap – between Conservation to Release Rigidity threatens system when leadership won’t allow resources to be released to allow in new ideas, which sometimes happen when the cost/risk is seen as too high.

- Chronic disaster trap – between Release to Reorganization As resources are released some lose their way, making it difficult or impossible to move into the exploration phase impossible and begin testing out new ideas

- Poverty trap – between Reorganization to Exploitation When you are unable to reach a consensus on an idea, or unable to direct resources to introduce the best idea into the ecosystem.

- Parasitic trap – between Exploitation to Conservation People may steal your idea as it begins to experience success or otherwise challenge intellectual property, making it impossible for an organization or person to reap the benefit of the investment they made up until now. Systems get stuck when they are unable to reconcile with the type of standardization needed to move into the conservation space.

To foster the conditions for positive social innovation actors in different roles must work in concert — sometimes on very different timescales — to create systemic change.

Disruptive Role Those in disruptive roles will go against the grain, push against the system, see a new way of doing things. But disruption on its own is insufficient for progress and systems change.

Bridging Role Those in bridging roles need to be able to identify a valuable idea and translate it or adapt it so that it can be applied across the various parts of the system of interest. Bridging agents help create the conditions for success.

Receptive Role Those in receptive roles understand the territory, and know how to “work the system” to take the idea and scale it out or up for deep impact.

Helpful Resources

- “Social Innovation and Resilience: How One Enhances the Other,” F. Westley, Stanford Social Innovation Review, Summer 2013

Unit 4: Getting to Scale

The multi-level perspective (MLP) can be used to understand other aspects of change across a system.

The MLP is useful to understand how change happens over time, what conditions help create windows of opportunity, and how actors in disruptive, bridging and receptive roles (see Unit 3) may be involved in scaling a new initiative.

The process of scaling social innovations to achieve systemic impacts is multifacetted. Systems change is likely to require a combination of scaling up, out/wide, and deep.

- Scaling up requires a good understanding of the landscape, to identify opportunities and barriers at the institutional level and aim for system-wide change.

- Scaling out/wide is the process of spreading an innovation to more users.

- Scaling deep requires attention to contexts and the specific place-based cultural change that need to place as a result of an innovation.

It is important to remember that:

- There is no “right scale” for an innovation – talk of scales and levels should be used to understand change and help build capacity for impact.

- There is no need to re-invent the wheel. Not everyone needs to be a niche innovator, and not every niche innovation needs to be an invention. There is enormous potential in identifying niche innovation that already exist scale them up.

Tips for social innovation agents

- Reflect deeply first: there are multiple pathways for scaling with differing resources and enabling demands.

- Partner: powerful, dynamic scaling is cross-sectoral.

- See the guiding goal and purpose: in most cases the ultimate goal is towards prevention and triggering system change.

- Be a learner: all scaling modes and experiences generate learning capable of informing system change.

- Recognize the illusion of permanence: social innovations are not a fixed address.

- Be humble: we are in the earliest days of understanding the cultural context and drivers for system change.

Helpful Resources

- “Scaling Out, Scaling Up, Scaling Deep Strategies of Non-profits in Advancing Systemic Social Innovation,” Michele-Lee Moore, Darcy Riddell, and Dana Vocisano, ResearchGate, December 2015