By the end of this unit, participants will be able to:

- Develop a holistic understanding of approaches to systems change.

- Build capacity for action in areas of impact about which one is passionate.

- Illustrate ways of creating change from grassroots through to policy, as well as to anticipate unintended consequences of success.

Background

In social innovation and design spaces, even when we try to bring the whole system into the room, it is easy to feel removed from the “grassroots”, i.e. from the communities that will benefit from the change or from the programs and initiatives we develop and/or deliver. Without intentional and sustained attention to the communities who are the end-users of innovation, we incur the risk that our designs and ideas fail to have relevance for the very people they are intended to support.

Likewise, without an understanding of what is involved in persuading others of the necessity of introducing change, the creations of interventions to address societal challenge may fail before it even starts. This is why the work involved in advocating and pressing for the intentional change needed to address societal challenges at a systems level is part of social innovation. Understanding advocacy strategies and the role of activism in systems change work is important. It serves to amplify, assist and champion the work of changemakers by presenting new and useful opportunities to government and other policy stakeholders.

In this unit, we examine the main characteristic of a movement for change and pay special attention to approaches organizations can use to generate the will to act. We consider ways of working towards positive change, both through formal political channels and through other methods and tactics.

The case we study in this unit concerns the strategies for advocacy and activism that were deployed to establish marriage equality as a law in Ireland. While the topic itself can generate disagreement, the material we present intentionally remains neutral about the position one should adopt on the issue and students will not be invited to debate the law. We want to emphasize the importance we bestowed on political neutrality in devising this case study. The objective is not to debate the pros and cons of marriage equality from a moral standpoint, as this could create an emotionally charged atmosphere. The case study is entirely designed to maintain a safe and inclusive space in the classroom.

Core Concepts

Advocacy and Activism

Advocacy and activism are concepts that are likely to have a wide array of connotations. To avoid misunderstanding, it is helpful to agree on the meaning of words, as a working definition and to invite a discussion that can help make clear the assumptions people tend to make when discussing these terms.

Working Definitions

Advocacy

Advocacy (for something) is the action for a person or organisation of formally providing public support to an idea, a course of action or a belief. For instance, an organisation like Universities Canada advocates for Canadian universities with government at the federal level to make sure that the interest of universities are taken into account in federal policy.

Activism

Activism is the action of working to achieve political or social change, often on behalf of an organisation or an association with a specific purpose. For instance, the boycott of American products by Canadians in response to threats of increased tariffication and economic annexation by the President of the United States in 2025 was a form of grassroot activism. Protests, petitions and digital campaigns are other forms of activism.

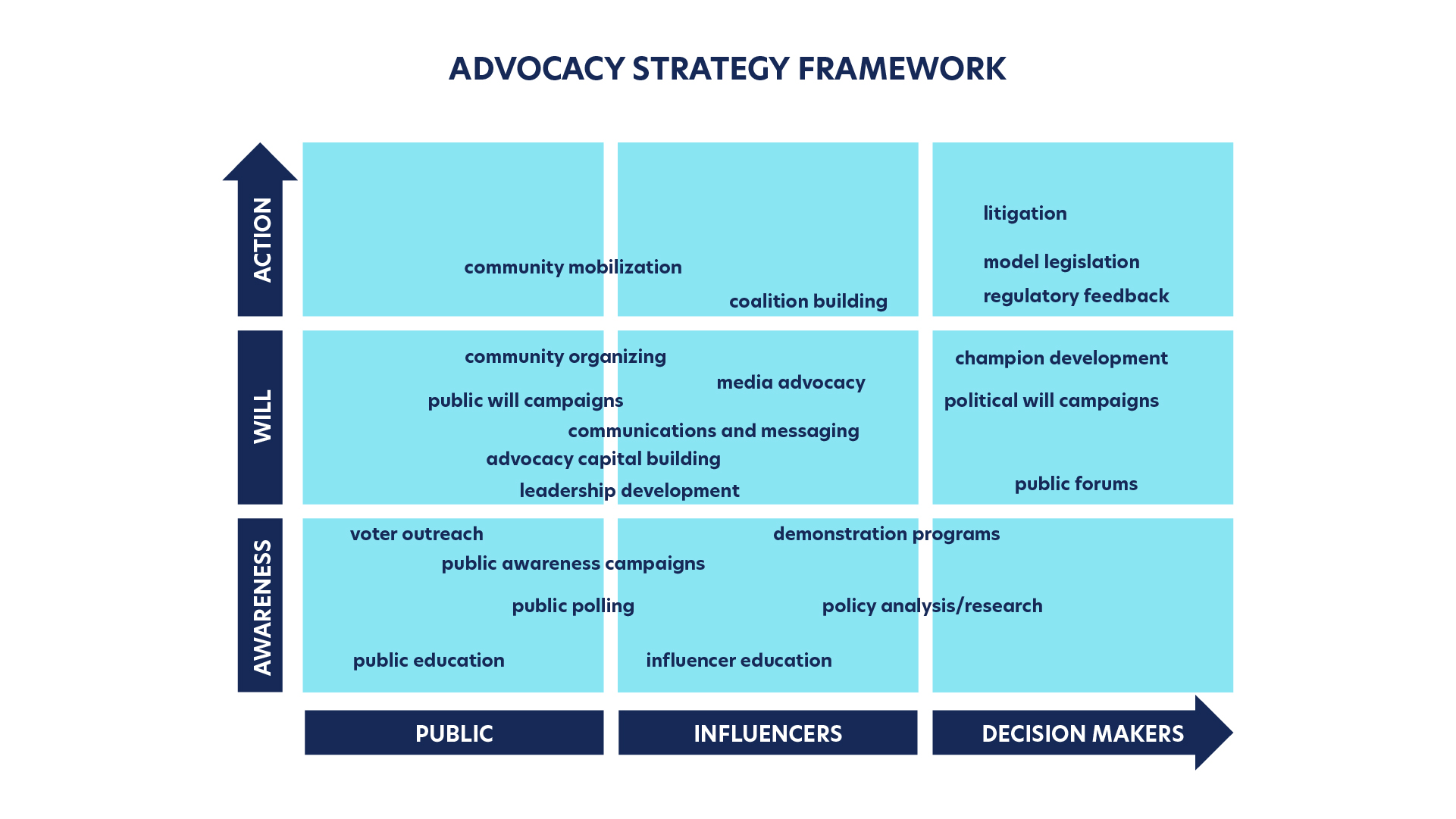

The Advocacy Strategy Framework

The Advocacy Strategy Framework is a tool for understanding and comparing different types of strategies and tactics that underlie public policy advocacy strategies, as well as their relations, in terms of both their intended outcomes and audiences. We will use it in this Unit as part of our case study. It revolved around 2 different axes: audiences and outcomes.

Figure 10.1. Advocacy Strategy Framework.

Audience

In the context of advocacy, an audience is constituted by the persons and groups a specific advocacy strategy targets and attempts to influence or persuade. Advocates typically target political audiences, i.e. actors in the relevant political space. But audiences may include the public (or specific segments of it, e.g. women), policy influencers (e.g., media, community leaders, the business community, thought leaders, political advisors, other advocacy organizations, etc.) and decision makers (e.g., elected officials, administrators, judges, etc.). An advocacy strategy may focus on just one audience or target more than one simultaneously.

In most cases, for an organization or a group to successfully advocate for policy change, they should do more than engage their audiences’ attention for the purpose of building awareness. They must also cultivate their will to change, i.e. to ignite their desire to act collectively and see that the change happens and produces (i.e. the desired outcomes; see Unit 8).

Since advocacy is deployed in social spaces that are embedded in the complex fabric of systems, the pathways to success are not linear and, since complexity is not deterministic, its outcomes are not fully predictable either. The Advocacy Strategy Framework offers a place to start. It helps advocates think more intentionally about their audiences—who is expected to change and how and what it will take to bring them to embrace the change. The Advocacy Strategy Framework can be used to conceptualize how other advocates (like-minded or in opposition) are positioned. It also prompts thinking about useful tactics and meaningful interim outcomes.

Outcomes

When building an advocacy strategy, it is useful to consider the role played by a person’s ability to make decision and initiate action – their ‘will’ – when it comes to making things happen. Awareness of an issue is not enough to drive action. The outcomes of an advocacy strategy depend on what happens between awareness and action and the ability to build audiences’ will to act.

According to the authors of the Advocacy Strategy Framework, successful advocacy generate the will to act and the latter can be understood across 5 dimensions:

The Advocacy Strategy Framework can be used to define the specific characteristic of different advocacy tactics by comparing them with respect to their audiences and outcomes.

- Education (public, influencer, policymaker).

- Public polling.

- Policy analysis and research.

- Public awareness campaigns.

- Voter outreach.

- Demonstration program.

- Leadership development.

- Advocacy capacity building.

- Public forums.

- Communications and messaging.

- Public-will campaigns.

- Media advocacy.

- Political will campaigns.

- Community organisation.

- Champion development.

- Coalition building.

- Regulatory feedback.

- Model legislation.

- Community mobilization.

- Litigation.

- Referendum.

These tactics can be understood in terms of their position across the Advocacy Strategy Framework, i.e. by determining how likely the tactic is to reach a specific audience (public, influencers, decision-makers; on the x-axis) and how far that tactic might realistically move the audience along the spectrum of awareness, toward action (on the y-axis).

A public awareness campaign, for example, is often the tactic employed to start a conversation. On one hand, it’s usually broad based and rarely seen as controversial. But the outcomes of a public awareness campaign are also limited to building awareness. To move the audiences’ will toward action, other tactics would likely need to be involved. On the other hand, litigation – recourse to legal action to transform policy – is used to command the attention of decision-makers and is action-oriented but it is a protracted process that can take years.

Case Study Notes

The Path to Marriage Equality in Ireland

Read the Case Study [link]

Main Actors

Gay and Lesbian Equality Network (GLEN): pushed to legalize civil unions first, before pushing for full marriage equality.

Marriage Equality: pushing for marriage equality, first and only.

Premise

The main disagreement between the Gay and Lesbian Equality Network (GLEN) and Marriage Equality was one of strategy (Case Study, pg. 1-2). GLEN assumed that the better approach would be to legalize civil unions first, before pushing for full marriage equality. On the contrary, Marriage Equality wanted marriage equality to be the only and primary focus.

In addition to differences in the strategic focus of their campaign, GLEN and Marriage Equality were culturally different. GLEN was seen as an insider organization – working with politicians for change, while Marriage Equality was grassroots, deploying a range of tactics at local levels, while raising public consciousness across the country with the court case.

One thing GLEN and Marriage Equality agreed on was that a referendum was the only way to get full marriage rights. A referendum is the practice of submitting to popular vote a measure passed on or proposed by a legislative body or by popular initiative. This was a pivotal decision tactic-wise. Once GLEN and Marriage Equality had decided on a referendum; they had to set a course for how to get there.

Different Routes to Same-Sex Marriage: The Canadian Context

How same-sex marriage became legal in Canada

In Canada, jurisdictional powers over marriage are shared between federal and provincial levels of government. The Parliament of Canada has authority over “marriage and divorce” and the legislatures of the provinces have authority over “the solemnization of marriage in the province” (“Canada: The Constitution and same-sex marriage”, Peter W. Hogg. pg. 714, 2006).

Because of the specificity of Canadian governmental structures, same-sex marriage advocates in British Columbia, Ontario and Quebec successfully challenged the traditional definition of marriage based on Canada’s Charter Rights (added to the Constitution Act in 1982) in a series of successful Supreme Court cases that protected gay and lesbian equality rights. At the issue of these legal actions, same-sex couples were recognized as having the right to marry in the relevant provinces (2003, 2003, 2002 respectively). But at the federal level, the Constitution Act of 1867 still read that marriage was between “one man and one woman.”

The Federal Government asked the Supreme Court of Canada for an advisory opinion on whether the Parliament of Canada had the power to legalize same-sex marriage nationwide. They obtained confirmation in 2003 that they in fact did have the power to make that change and in 2005 The Civil Marriage Act was ratified. The Federal Government changed the definition of marriage to replace reference to a union between “one man and one woman” to a reference to a union between “two persons.”

The Federal Government’s decision to request an advisory opinion from the Supreme Court of Canada was significant. As Peter W. Hogg writes, “It is clear that the Civil Marriage Act is legally valid because the Government of Canada obtained advance clearance regarding its constitutionality from the Supreme Court of Canada in Re Same-Sex Marriage (2004). The Government of Canada had in 2003 directed a ‘reference’ to the Supreme Court of Canada, asking the Court for an advisory opinion as to whether the Parliament of Canada, which has legislative authority over ‘marriage,’ had the power to legalize same-sex marriage” (Hogg, pg. 712, 2006).

The case against the Civil Marriage Act came from those who argued that same-sex relationships could not have been the understanding of the framers of the Constitution Act in 1867, “when marriage and religion were inseparable and homosexual acts between consenting adults were criminal (as they remained until 1969). And this understanding should not be extended in such fashion today, since marriage was, by its very nature, the union of a man and a woman with a view to the procreation of children” (Hogg, pg. 717, 2006).

The Court rejected this argument and denied that it was bound to the original understanding of the Constitution Act. In its rejection, the Court reaffirmed its “oft-expressed view that ‘our Constitution is a living tree which, by way of progressive interpretation, accommodates and addresses the realities of modern life’” (Hogg, pg. 717, 2006).

The position that marriage was largely an arrangement with a religious basis – between a man and a woman for the purposes of procreation – had been commonplace for generations; so much so, that when the quest for same sex marriage began, some people in the 2SLGBTQIA+ community objected to the initiative altogether. They argued vehemently against adopting a heteronormative position, concerned that the focus on marriage alone would distract from broader fights for equal rights. Many also took a principled position on rejecting a heterosexual ritual based on religion. Because actors and legal and governmental structures in Canada are distinct, different strategies were employed and the route to country-wide legalization of same-sex marriage followed a path different from the one travelled in Ireland.

Understanding advocacy strategies and the role of activism in systems change work is crucial. It can serve, amplify, assist and introduce changemakers in government and other institutions to the work in which you are involved and result in new and useful opportunities.

Advocacy (for something) is the action for a person or organisation of formally providing public support to an idea, a course of action or a belief. Activism is the action of working to achieve political or social change, often on behalf of an organisation or an association with a specific purpose.

The Advocacy Strategy Framework is a visual tool for thinking about the strategies and tactics that underlie public policy advocacy strategies.

Audiences are the individuals and groups advocacy strategies target and attempt to influence or persuade. They represent the main actors in the policy process and include the public (or specific segments of it), policy influencers (e.g., media, community leaders, the business community, thought leaders, political advisors, other advocacy organizations, etc.), and decision makers (e.g., elected officials, administrators, judges, etc.). Strategies may focus on just one audience or target more than one simultaneously.

A person’s ability to make decision and initiate action – their ‘will’ – is a function of the progression of their opinion on the issue from awareness to action.

Successful advocacy, the ability to generate the will to act can be understood to involve five elements [link] :

- Opinion. People need to take a position on an issue for will to be built.

- Intensity. People need to hold their opinions strongly—either for or against an issue or a solution—before it rises to a level worthy of their time and attention.

- Salience. People may hold a strong opinion about an issue, yet still not find that the issue is relevant enough to their lives to make political choices based on the issue.

- Capacity to act. Innovation actors need the know-how, skills, and confidence to take the desired action when called upon.

- Willingness to act. Innovation actors need to be in a position to want to take action, often despite the risks or trade-offs that associated with it.

Slides

Partner Engagement

Assignments

References