By the end of this unit, participants will be able to:

- Apply the notion of “stretch collaboration” and compare it to more conventional models of collaboration.

- Appreciate the role of self-examination in collaborative settings.

- Use the collaboration spectrum to describe collaborative relationships and partnerships.

- Identify the three core challenges to partnerships and collaborations — and how to address them.

Background

The purpose of Unit 5 is to introduce students to some important aspects of collaboration in settings where complexity exists. Complexity is always a factor influencing collaborations that span across ecosystems. Unit 5 applies the theory of social innovation and its core concepts to active forms of mutual engagement and the practical contexts in which they occur.

Collaboration is an important aspect of social innovation in the real world: one cannot generate systems change alone and social innovation is an “all-hands-on-deck” type of journey. Unit 5 considers one’s role in inclusive collaborative teams. A critical element in teamwork is knowing that every team member brings a different combination of strengths and assets to the table. And that, when we collaborate, we all bring individual perspectives, expertise and lived experience that can enrich the outcome.

Working together on a project can sometimes feel like what happens in the often-cited allegory of the elephant being examined by multiple blindfolded individuals through their sense of touch and attempting to describe it as a whole. The tactile perspective of each person, each placed in a different position around the elephant is at once privileged and limited. Separately, they might not be able to come to recognise the elephant. It’s only once they put their perspectives together that they can get a fuller picture.

Core Concepts

The Collaboration Spectrum

Collaboration happens when at least two actors, whether they are people or organizations, “work together”. Organizations in a system are connected in a way that is far from binary. The question when considering any two organizations in a system (say a community) is not simply: ‘Do they collaborate or not?”. Two organizations may have no connection, in which case they merely co-exist in that system. However, when they are connected, the interactions between them can take a variety of forms. For instance, two organizations may:

- Compete for clients, resources, partners or visibility

- Engage in informal interactions around specific projects

- Shared missions or goals that make it relevant and desirable that they intentionally create synergies

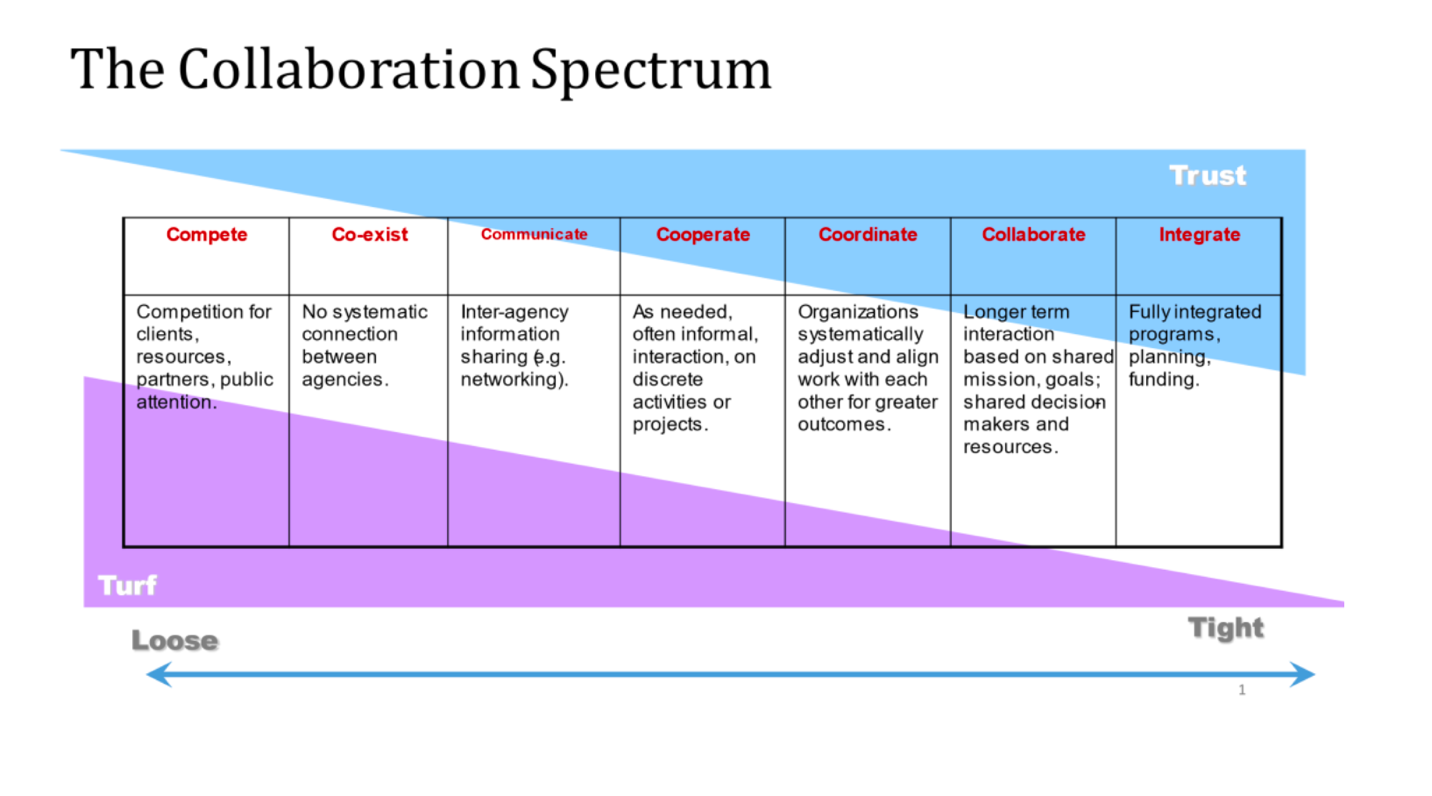

Liz Weaver, one of the founding CEOs of the Tamarck Institute for Community Engagement, proposes that we think of collaboration on a spectrum: collaborations may revolve around different goals, actions or activities that determine the relative alignment in their relationship.

The Collaboration Spectrum is articulated around the idea that interactions can be more or less, loose or tight and that they involve different levels of trust. Two organizations who co-exist or compete are more loosely linked and they might be more protective of their “turf”. When organizations are intentionally coordinating and integrating services, programs, or governance, we can speak of a partnership that require levels of trust proportional to the level of integration that is pursued.

Figure 5.1. The Collaboration Spectrum. Courtesy of Tamarack Institute.

Figure 5.1. The Collaboration Spectrum. Courtesy of Tamarack Institute.

Shared ownership

One of the biggest challenges facing collective and collaborative efforts is getting individuals and organizations to proactively commit to contribute resources, knowledge and expertise toward shared ownership and to calibrate their expectations regarding these commitments.

Shared ownership is about deliberately considering how the mission and goals of your home organization align with and potentially can contribute to the shared outcomes of the collaborative effort. Shared ownership is successful when partners understand the shared purpose of the collaboration and contribute to shared leadership and shared outcomes.

It’s good to always remember that shared purpose, shared leadership, shared outcomes and share ownership may take different forms. In teamwork as in other work and life, sometimes different approaches or combinations of approaches are needed to get things done. In the realm of social innovation, actors should assume that sophisticated collaborative efforts will be needed. Shared ownership is vital in social innovation and when working towards transformation, the skills, talents, resources and commitment of actors is fundamental.

Stretch Collaboration

The dynamics that underpin collaborative interaction and partnerships are complex. Engaging in collaboration requires insights that pertain to the psychology of group dynamics, power and equity. In some contexts, there is a need to go beyond standard theories and approaches to collaboration.

Standard approach to project-based collaboration generally revolves around the collective answers a group provides to the following type of questions:

- What is our common purpose?

- What is the problem?

- What is the solution to the problem?

- What is the plan to execute the solution?

- Who need to do what to execute the plan?

There would be nothing intrinsically wrong with a collaboration that would be informed by an answer to these five questions. But such a collaboration would rest on some significant assumptions that could limit its scope and its success. For example, question 1 assumes there is a common purpose and that collaboration is happening in a context where those involved are agreeable to working together, i.e. that they are motivated to find a solution that works for everyone. However, this is not always the case. Sometimes – or indeed often in contexts where complexity is involved – we are forced to collaborate with people whose values we don’t share, or in contexts where perspectives may seem to clash.

In “How to collaborate when you don’t have consensus” Adam Kahane suggests a different approach to collaborative work, one he associates with tools designed to “stretch” collaboration in situations where standard approaches are likely to fail. He cites three principles that may help steer collaborative work in the right direction when complexity is involved.

Other models of governance (for instance, those based on what Gerard Endenburg called the Sociocratic Circle-Organization Method) are specifically designed to foster psychological safety that is needed for fruitful collaboration. They introduce alternative approaches to decision making. For instance, instead of relying on majority voting, they promote the uses a consent-based among people who share a common goal or work process.

Trust plays a vital role in collaborative governance processes, as members need to build mutual trust for the model to succeed. When trust exists between interactions and partnerships, there exists active engagement with nearby community members which can foster local involvement and lead to a foundation for higher levels of governance.

Self-examination

In some situations, obstacle to collaboration may come from “within”. We are all familiar with the many ways in which social interactions are affected and driven by our own perceptions, biases and emotions. Even in the best conditions, we may fail to understand the contribution we could make, or fail to understand how our assumptions or biases prevent us from doing our best work. Everyone is likely to feel stuck or go through a rough patch. Certain situations can trigger us because similar situations in the past affected us negatively. We may also have preconceptions about how teams should work that prevent us from being adaptable or appreciate a new perspective. These are all cases where the barrier to fruitful collaboration lies within us: we are self-sabotaging.

What the two allegories – Jung’s shadow-self and the myth of Nemesis – have in common are two things. First, they both come with the fatalistic notion that there is no escape. Second, they also assume that coming to terms with our shadow-self or with our Nemesis is a matter of restoring balance.

These two things seem to be equally true when it comes to building the sort of integrity required to justify positions we take, the actions we pursue and collaborations in which we engage when working towards change. A lack of inner balance needs to be addressed and this can only be done through reflection and self-examination. The same holds in our relationship with others.

In the context of social innovation and systems change, the notion that there is a benefit to seeing a problem as residing both inside oneself as well as outside oneself, is significant. In the context of social innovation, where the multiplicity of perspectives is the basis of all collaboration, some of the “problems” we encounter can often have their roots in collaborators’ own perceptions.

Since actors in a system are part of both the problem and the solution, the work of social innovation is inherently human and social. As a result, breaking through social innovation eventually requires self-examination and reflection. For instance, reflecting intentionally on the reasons why conflict may arise amongst participants may be key to an impass and unlock new ways of thinking and approaches.

Collaborative innovation and the sort of breakthrough that can only happen if working together requires some level of disagreement and in some case conflict. When we work within a system with the objective to transform it, we don’t get to decide who can be included and who cannot. We cannot pick and choose system systems actors: the system does that for us. As a result, while we can try to ignore the facts, the people and the circumstances or suppress the emotions that make us feel uncomfortable or don’t align with or value, they don’t go away; they don’t stop being a part of the systems we are working to change. True collaborative innovation requires everyone’s involvement

Reflection and self-examination, especially when conflict arises, can help us discern what each actor is bringing to the collaboration. Reflecting on the way to reconcile dissonant views and approaches may in fact be the fastest way to gain a fuller understanding of the issue from a systems perspective. It can help “unstick” our thinking and approaches.

Partnerships

To collaborate effectively, one must be able to work with different people and/or organizations, some with more power and resources, some with less. Partnering begins with the recognition that the purpose of collaboration is to achieve more together than we would working separately. A partnership is a way to secure additional resources to achieve the desired outcomes.

The hypothesis underpinning partnered approaches to social innovation and impact is that comprehensive and widespread cross-sector collaboration is needed to ensure that initiatives designed to tackle stuck problems and wicked social and environmental issues are genuinely innovative as well as sufficiently coherent and integrated. Generally speaking, cross-sectoral collaboration presents the best chances to achieve shared and positive outcomes. Specifically, cross-sectoral and/or multi-sectoral approaches are needed to streamline relationships between the education, community, industry and government sectors to innovate in a way that is genuinely socially transformative. This is because the talent, assets and perspectives required to address complex issues belong to all dimensions of the system.

Cross-sectoral partnerships

Single sector/organization approaches to social innovation generally prove inadequate. When organizations or clusters of organizations in a sector merely co-exist or compete, they tend to duplicate efforts and waste valuable resources. In such context, the responsibility for outcomes is also understood to be owned by single entities, the counterpart of which is a ‘blame culture’ where chaos or neglect is always regarded as someone else’s fault and no one is ultimately held accountable.

Partnerships provide an opportunity to approach challenges and outcomes collectively, distributing both the burden and the credit of collaborative initiatives. Cross sectoral partnerships are needed to insure that all the skills and resources needed to tackle complex issues are available and key to success is to find new ways to harness these skills and resources in spite of the institutional barriers that may exist.

Overcoming the Challenges of Partnership and Collaboration

‘My way or the highway’ leads nowhere.

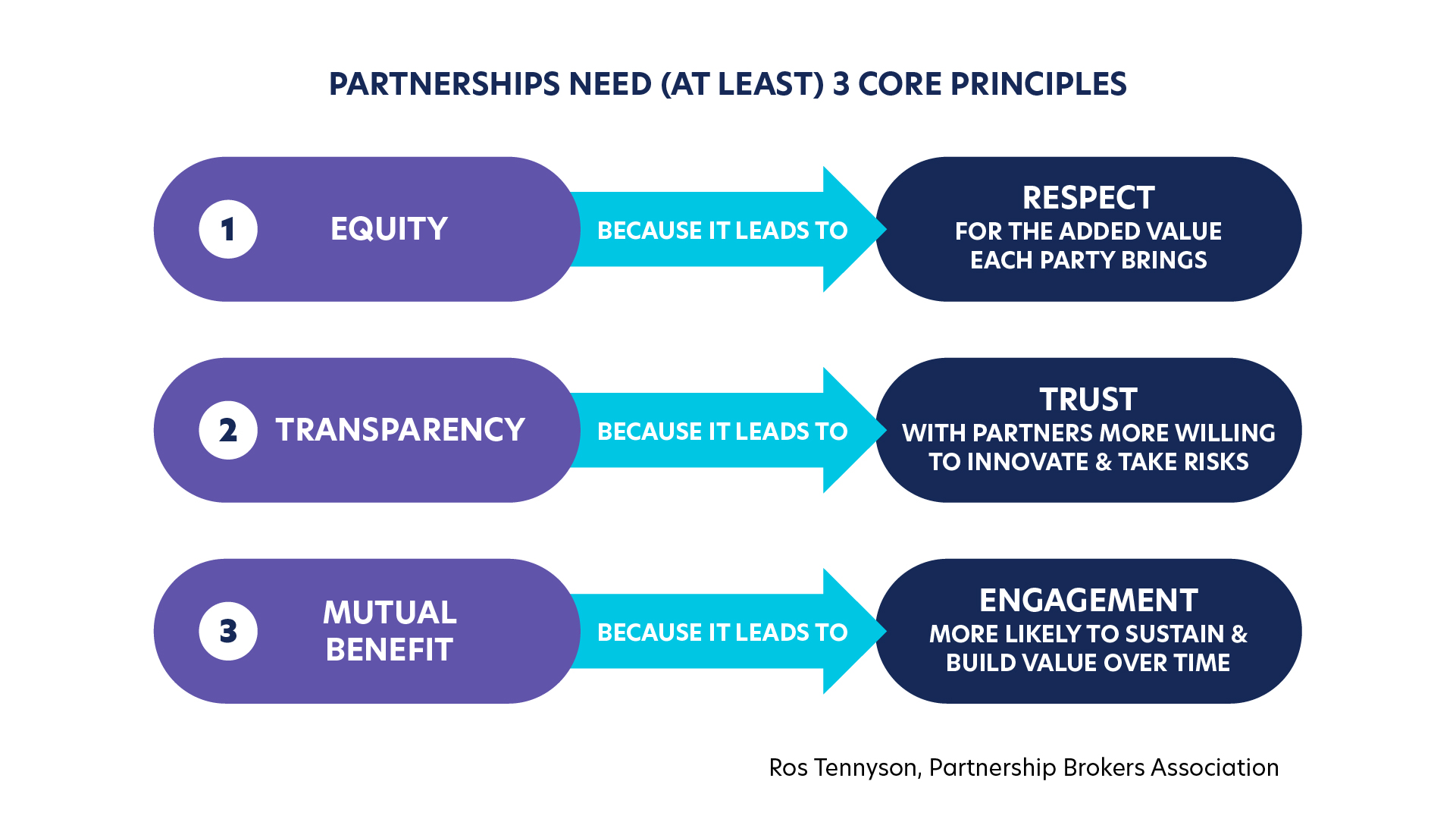

According to the Partnership Brokers Association, the three most common obstacles to collaboration are:

- Power imbalances

- Lack of transparency

- Intense competitiveness

These are widespread features of systems in which trust is low and competition is pervasive.

Key to fostering a collective approach to responsibility and ownership in cross-sectoral innovation settings is to replace attitudes that lead to power inequities, hidden agendas and hostile rivalry with attitudes that foster respect, trust and sustainable engagement.

A partnership that shifts from a state in which power is unevenly distributed to one in which equity is a guiding principle leads to respect. Likewise, shifting from a culture in which partners are allowed to pursue hidden agendas to a culture of transparency will increase trust. And a partnership in which actors operate for mutual benefit instead of their private gain will foster engagement and sustainability.

Core principles that lead to respect, trust and engagement are crucial given the dynamic nature of community change and the increased challenges a constant state of flow represents for collaborators. Applied across a system, respect, trust and engagement foster connectivity. In turn, connectivity that rests on respect, trust and engagement is needed to increase the capacity of a system to transform without getting stuck.

Figure 5.2. Core Principles of Partnerships.

Core principles such as those we proposed here are crucial to:

- Ensure equity and engagement around collaboration.

- Learn to navigate complex problems or social challenges.

- Establish a “good enough” balance between the process of governance and the shared outcome the collaborative effort is seeking to achieve.

- Develop strategies that build trust, address power dynamics, navigate shifting accountabilities and effectively manage the ups and downs of everyday life.

Collaboration is not for the faint of heart. It is purposeful action, where partners are seeking to accomplish together that which they would not be able to accomplish on their own. The Collaborative Spectrum (Unit 5) can help navigate partnerships.

The common approach to collaboration focuses on getting agreement on:

- What is our common purpose?

- What is the problem?

- What is the solution to the problem?

- What is the plan to execute the solution?

- Who needs to do what to execute the plan?

The common approach however does not apply in to collaborations in which agreement is not easy to achieve, as is the case in most situation where the perspectives of those involved are diverse and the collaboration pertains to a complex issue.

In these contexts, stretch collaboration is a better approach:

- Accept the plurality of the situation: You do not have to agree on what the solution is – or even what the problem is – to make progress. Different actors may support the same outcome for different reasons.

- Experiment to find a way forward: Keep trying things with the understanding that you can’t control the future, but you can influence it. Success isn’t coming up with a solution – it’s working toward one.

- See yourself as part of the problem, not outside it: You can’t make progress until you realize that you have a role in the situation. If you don’t see that you are part of the problem, you can’t be part of the solution.

Collaboration around social innovation requires cross-sectoral partnerships and work with people and organizations who may have more or less power and resources than ourselves. Ensuring that initiatives are creative, coherent and integrated enough to tackle the most stuck problems requires comprehensive and widespread cross-sector collaboration.

In a social innovation context, the lack of connectivity across sector different sectors often leads to competition, duplication of efforts and waste of resources which, in turn, might mean getting stuck in cycles of blame.