Lesson 2.1: Encouraging Employees to Engage with Workplace Innovation

Introduction

As observed in the ENWIN Case Story in Lesson 1.3, organizations supporting employee-led workplace innovation encourage employee ‘ownership’ of innovation projects. Rather than having specific innovation activities assigned as part of their day-to-day work assignments, employees are expected to decide on their own about innovations to pursue:

- Identifying opportunities for workplace innovation and initiating an appropriate project (in cooperation with their managers, including other employees as team members, and using the support of organizational innovation resources); and/or

- Choosing to take on self-selected roles in innovation projects initiated by other employees or made available as part of the organizational innovation strategy (as discussed in Lesson 2.2).

Encouraging and supporting this employee-directed innovation process requires an understanding of the day-to-day factors which motivate employees to engage in workplace innovation (or that hinder that motivation). Using that knowledge about employee motivation to innovate, workplace conditions can be created which will enable full employee engagement in Innovation activities and determine the optimal methods and tools to support each type of employee-led innovation activity (in later Lessons).

In this Lesson, two complementary knowledge perspectives on employee motivation to innovate will be encountered. The first is from Canada: recent research by Dr. Terry Soleas at Queen’s University which used data from employees identified as innovation leaders in their workplaces. The research process is summarized in a text box below, and results are presented as a five-point checklist of Factors that Influence Employee Motivation for Innovation.

The second part of the lesson details research insights on exemplary practices and methods to increase those factors that are associated with more motivation for innovation and decrease the impact of factors associated with less motivation for innovation. Most of this research comes from Europe, and which will be explored later how to help workplaces in Canada to adapt and customize these exemplary practices for our contexts. An opportunity to apply this knowledge comes in a Practice Exercise (with the Case Story in Lesson 2.3.)

Learning Outcomes

By the end of this activity, learners will have developed the capability to:

- Identify the variety of factors known to increase or decrease motivation for innovation

- choose, from a set of research insights and exemplary practices, the most promising to be explored further to inform how innovation leaders and catalysts could address specific issues in employee motivation for innovation in their workplace contexts.

Workplace Factors that Influence Employee Motivation to Engage in Innovation Activities

Research Process Summary: Dr. Terry Soleas clarifies the factors that influence employee motivation to engage with workplace innovation (Soleas 2020, 2021). This research adapted a common framework used for assessing motivation in the workplace, the Expectancy-Value-Costs model (Flake et al 2015), beginning with an initial study of 30 recognized Canadian workplace innovators. The resulting prototype survey instrument, the Motivation to Innovate Inventory, was then iteratively refined in prototype tests with another 500 Canadians identified as leading innovators in their workplaces. The Case Story of a Canadian workplace in Lesson 2.3 illustrates how these results can be applied.

In Dr. Soleas’ research, the following factors were shown to have positive associations with increased motivation to innovate:

- Positive Self-Concept as an Innovator (i.e., Identity and Self-Efficacy) raises expectations for the success of innovation and can help motivate initial and ongoing engagement in innovation projects. Conversely, if you do not think of yourself as an innovator then you are not likely eager to initiate an innovation project or volunteer your time on someone else’s proposed activity.

- Personal Enjoyment of the innovation process helps to sustain energy and engagement during an innovation project and can increase motivation for future innovation activities. Since inclusive workplace innovation is an inherently social process, collegial teamwork practices are critical to personal task enjoyment and engagement.

- Direct Benefit from the changes resulting from an innovation project is embedded in the definition of Inclusive Workplace Innovation: as “both participating in and benefiting from innovation activities”. The primary benefit is typically an improvement in employee quality of work life; there are other examples where an improvement in efficiency or product quality has helped the organization to be more competitive and thus helped to preserve employee jobs.

- Personal Value from the further impacts of an innovation project also has a positive association with employee engagement in workplace innovation. This could be at a personal level – e.g., receiving recognition, prestige or a financial reward based on the results of the innovation. The personal value to employees could also be derived from the wider impacts of an innovation, such as environmental or social impacts.

And one negative factor that emerged in the research study with Canadian workplace innovators is associated with lower motivation to engage in innovation activities (and therefore is something that Innovation Catalysts will want to reduce as much as possible):

-

Figure 2.1.2 – Negative Associations with Increased Motivation to Innovate Personal Costs of the innovation activity (expected or experienced) involves the psychological and contextual demands of innovation activities which an innovation team member finds noticeable arduous. Here are some examples (to be explored further below):

-

- Different innovation activities involve varying levels of uncertainty and risk. Some team members may find a particular level of uncertainty to be stressful, e.g., in a Design Innovation activity where the original stated goal of a project changes as more information becomes available.

-

- On the other hand, some innovation team members can find the innovation process more exciting than their day-to-day tasks and commit extra time or energy to these novel activities. That can have repercussions on their other work commitments and their work-life balance, with negative effects on their future motivation to engage in workplace innovation.

Exemplary Practices to Foster Employee Motivation for Innovation Activities

Moving from research-based understanding of underlying factors to practice-based improvements in innovation processes and support, one can identify practical methods which workplace innovation leaders and team members can apply to fire up and sustain engagement in workplace innovation – across a broad range of employee roles, capabilities and mindsets. In this section, learners will have the opportunity to develop their capability in relating research insights to issues in motivation to innovate in workplace contexts.

- Enhancing Self-Concept as an Innovator: building identity and self-efficacy

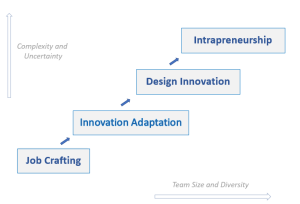

Engaging a broad range of employees in workplace innovation often requires reaching out to people whose initial conceptions of innovation – and of themselves as innovators – leads to ruling themselves out (“just not me”). Research in Europe has shown that a progression of workplace innovation activities can begin with simple examples that workers who have not thought of themselves as innovators can easily relate to and see themselves taking on (Høyrup 2012). Through a step-by-step progression, they can develop more confidence in their ability and identity as innovators, with assurance that they will be the ones to decide their own comfort level in terms of the complexity and uncertainty they take on.

Learners may have already encountered this concept of a progressive sequence of innovation activities in a previous study of workplace innovation; it has also arisen in research with Canadian employers to help employees develop identity and self-efficacy as innovators, using the progressive sequence in Figure 2.1. This particular progression begins with Job Crafting, an exercise which has been undertaken by employees across a wide range of occupations (Dutton & Wrzesniewski 2020) but has not often been positioned as a first step in engaging with workplace innovation. Once employees develop capability and confidence from their experience with Job Crafting, they can build on that foundation as they stretch further into Innovation Adaptation and Design Innovation activities.

- Engaging in an appealing social process and personal development in innovation

One key incentive for employee engagement in workplace innovation is a rewarding personal experience with the work process of an innovation activity. Innovation Catalysts and innovation project leaders can ensure employees have a positive and wholesome experience through:

-

- Their personal involvement in innovation task processes

- A sense of community from the social aspects of the process

- Respect, recognition and appreciation for their personal contributions

- A sense of accomplishment in developing their own personal capability

To foster an engaging innovation process, each employee can be helped to focus on roles where they can contribute the most and achieve optimal satisfaction (e.g., Julian 2016; Liedtka et al 2022) by leaders, Innovation Catalysts and coaches. Project leaders can also facilitate a sense of community amongst team members.

The sense of accomplishment from personal capability development within a particular activity can also be enhanced through “stackable” capabilities as shown in Figure 2.1 above, where the Skills and Knowledge for more complex, uncertain, and impactful innovation activities build on the capability developed for simpler innovation activities with smaller teams (Nobis et al 2022).

Employees also note how their involvement in workplace innovation results in personal development beyond the workplace: “Going deep with design requires more than changing the activities of innovators; it involves creating the conditions that shape who they become. Individuals become design thinkers by experiencing design…Ultimately, innovators need to see themselves becoming someone new as they create something new”. (Liedtka et al 2021)

- Benefiting Directly from Changes arising in an innovation

The European conception of Employee-led Workplace Innovation emphasizes “win-win outcomes for companies and people: high levels of economic performance, high quality of working life and a high skill equilibrium” (Totterdill & Eyton 2021). A growing body of evidence indicates that workplaces can adopt practices which promote these multiple goals and that these transformed workplaces can provide mutual gains for employers and for employees. As the text box below illustrates, innovation project leaders and their supporting Innovation

Catalysts will want to ensure that this win-win approach is central for innovation projects.

Workplace innovation projects typically address problems that emerge in the course of everyday work as workers encounter conditions ‘on the ground’ that are complex, situated, and emergent. The knowledge of these problems is often tacit…deeply embedded in ‘street-knowledge’ and therefore difficult, costly, and time-consuming to transfer to individuals not engaged in the particular front-line practices…When employees experience these problem situations, they often do so personally and directly. This means that the primary incentive for employee innovation to overcome these problems will therefore typically be to benefit from using the solution themselves.

(Hartmann & Hartmann 2020)

- Valuing the Further Impacts of an innovation project

When the organizational culture supports employee identification with the success of the organization, employee innovation can be increased through the beneficial impacts of the innovation results within the organization. Employee motivation can increase when they see the impact of their innovation projects can include bolstering the economic and social well-being of the company or agency or preserving local jobs and contributing to community prosperity.

As noted above, some workplace innovation projects will also align with larger employee goals beyond the firm. For example, environmental impacts of workplace activities are a growing concern for many employees. The promise of more sustainable communities through related workplace innovation projects can therefore increase the value perceived by employees and boost motivation for their further engagement.

We should note that one practice often suggested to increase employee motivation is financial incentives for project success. Research on special innovation-specific financial incentives for engaging in innovation projects suggests that this can be counter-productive, because it can diminish the cultural expectation that “innovation is everyone’s job” (Karin et al 2010; Sanders et al 2018; Dehvari & Wenner 2020). As well, when financial incentives are linked to the “success” of an innovation project – as defined by its original proposed goals – then employee motivation to tackles more ambitious and uncertain projects can be diminished (Fernandez & Moldogaziev 2013; Sanders et al 2018). This topic will be addressed again later in a deeper discussion or Organizational Culture and Workplace Innovation.

- Reducing Perceived Costs in workplace innovation projects

Some of the negative Cost factors raised above are generic to demanding work conditions, such as work engagement disrupting work-life balance. The focus here is on scenarios more specific to innovation projects and suggests practices that can be used to help mitigate potential negative effects on motivation to innovate. (A third scenario will arise from the Case Story in Lesson 2.3),

Here are two scenarios that have been raised with us by workplace partners as potential sources of discouraging results and employee concern:

-

-

- When employees experience ‘negative results’ arising during a workplace innovation process, e.g., when a key hypothesis for the current design approach is proven to be faulty and the resulting innovation project pivot seems to be a step backwards to redo work that was thought to have been completed. This concept will be discussed further in a later Lesson about how to plan early prototype tests for the most critical hypotheses in a project rationale (an innovation practice called Hypothesis-driven Prototyping)

- When employees experience apparently ‘negative results’ as a conclusion to a workplace innovation process, e.g., a project concludes without reaching the goals the innovation team had hoped for (as in “we now know that our organization should not be pursuing this direction at this time”). This scenario will be addressed in further detail in Lesson 2.3,

References for 2.1 – Encouraging Employees to Engage with Workplace Innovation

Dehvari, S., & Wenner, M. (2020). Managing internal ideation: A Case study at Bengt Dahlgren. Stockholm AB. Master’s Thesis, KTH Royal Institute of Technology.

Dutton, J. E., & Wrzesniewski, A. (2020). What job crafting looks like. Harvard Business Review online.

Fernandez, S., & Moldogaziev, T. (2013). Using employee empowerment to encourage innovative behavior in the public sector. Journal of public administration research and theory, 23(1), 155-187.

Flake, J.K., Barron, K.E., Hulleman, C., McCoach, B.D., & Welsh, M. E. (2015). Measuring cost: The forgotten component of expectancy-value theory. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 41, 232–244.

Høyrup, S. (2012), “Employee-driven innovation: a new phenomenon, concept and mode of innovation”, in Høyrup, S., et al (Eds), Employee-driven Innovation: A New Approach, Palgrave Macmillan, Basingstoke, pp. 3-33.

Julian, T. (2016). Roles Table in the “Encourage Every Employee To Play A Role” section of A Guide To Changing The Innovation Climate In Your Organisation. Hargraves Institute, Cammeray NSW Australia. p. 11.

Karin, S., Matthijs, M., Nicole, T., Sandra, G., & Claudia, G. (2010). How to support innovative behaviour? The role of LMX and satisfaction with HR practices. Technology and investment, 2010.

Liedtka, J., Hold, K., & Eldridge, J. (2021). Part Four: Different Strokes for Different Folks. In Experiencing design: The innovator’s journey. Columbia University Press.

Nobis, F., Stevenson, M. Baregheh, A., and T. Carey (2022). Engaging Students with an Adaptable Model for Workplace Innovation Capability. In Case Stories: Innovation & Entrepreneurship Teaching Excellence Awards 2022.

Sanders, K., et al (2018). Performance‐based rewards and innovative behaviors. Human Resource Management, 57(6), 1455-1468.

Soleas, E. K. (2020). What Factors and Experiences Motivate Innovators? An Expectancy-Value-Cost Approach to Promoting Student Innovation (Doctoral dissertation, Queen’s University, Canada).

Soleas, E. (2021). Environmental factors impacting the motivation to innovate: a systematic review. Journal of Innovation and Entrepreneurship, 10(1), 1-18.

Totterdill, P., & Exton, R. (2021). Workplace Innovation in Practice: Experiences from the UK. In The Palgrave Handbook of Workplace Innovation (pp. 57-78). Palgrave Macmillan, Cham. p. 63.

-