7.6 Levers

The human body is made up of bones and muscles, which allow it to move as required. But how exactly do they produce movement? Well, if you have some knowledge of muscles, you might already know that they produce movement by contracting where, when, and how much we need them to. However, because the body is complex and requires sophisticated movements in a variety of planes, how bones and muscles are connected differs throughout the body.

Bones and muscles act together, as a lever, to move the body. Within each lever system are the following components:

- Lever Arm: A “bar-like” structure which is used to transmit force.

- Fulcrum: Where the lever arm (or joint) pivots. Also known as “axis of rotation”.

- Resistive Force (Load): Force acting to prevent motion.

- Applied Force (Effort): Typically causes the motion and is often triggered via muscle contraction.

When arranged differently, these components can help the body:

- Balance two or more forces;

- Provide a force advantage where less effort is required to overcome a greater resistance, or;

- Provide an advantage in speed of movement whereby the load moves further and faster than the effort force.

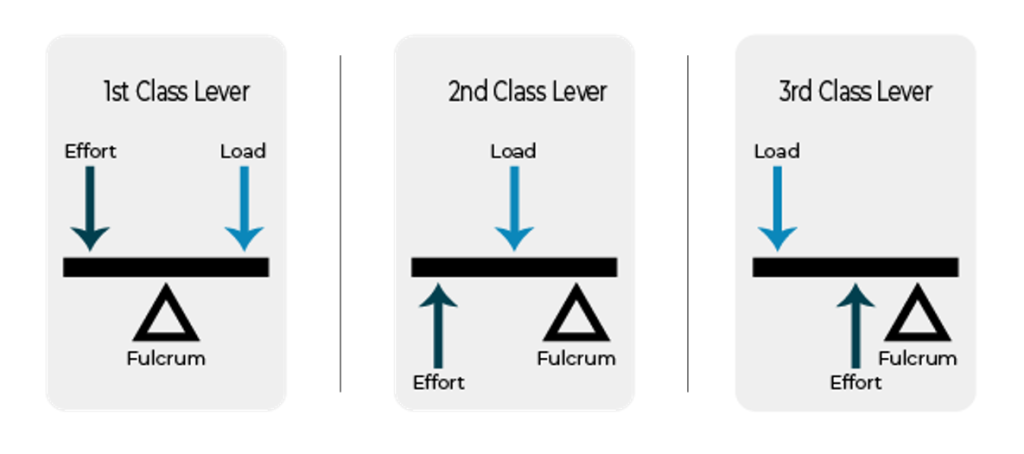

Levers within the body accomplish this by existing as either a first, second, or third-class lever:

Class Levers

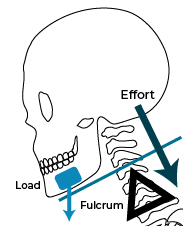

First-class levers are the simplest types of lever, where the two forces, the load and the effort, are applied on opposite sides of the fulcrum. In the body, the best example of a first-class lever is the way your head is raised off your chest. With the atlanto-occipital joint (the spinal column-skull joint) acting as the fulcrum, the posterior neck muscles produce the effort, and the mass of the facial skeleton is the resistance. When you lift your head up and down, this lever system acts like a seesaw.

Second-Class Levers

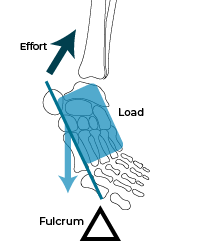

Second-class levers differ in that the load and the effort exist on the same side relative to the fulcrum. The effort, however, is closer to the load than the fulcrum, which allows a large resistance to be moved by a small amount of effort. However, this means that the resistance will be moved at a relatively slow pace and can only be moved a short distance. An example of this within the body would be your calf muscles. In this scenario, the weight of your body acts as the load, your calf muscles as the effort, and the balls of your feet as the fulcrum.

Third-Class Levers

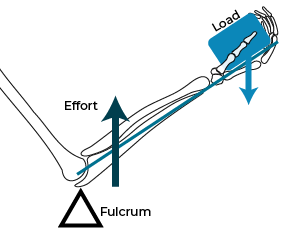

Third-class levers are the most common type of lever in your body. The effort is applied between the fulcrum and the resistance, which allows the resistance to be moved relatively quickly over large distances. An example within the body is when you lift your hand by flexing your biceps brachii. In this scenario, your elbow acts as the fulcrum, the biceps brachii produces the effort, and the weight of your hand is the load being lifted.

“Chapter 12. Biomechanics” from Human Anatomy and Physiology I by Priscilla Stewart is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, except where otherwise noted.