11.2 Skeletal Muscle Anatomy

Located throughout the body, skeletal muscle contractions produce movement that enables us to engage in physical activity and exercise. But how exactly does it do it? To understand how this occurs, you will need a basic knowledge of anatomy and the structure of skeletal muscle.

Anatomy of Skeletal Muscle

Click on each icon to learn more about the different parts that make up skeletal muscle.

Text Description

An anatomical diagram of skeletal muscle structure showing the layers from whole muscle to myofibril. The image labels the muscle belly, epimysium, perimysium, endomysium, fascicle, muscle fibre, sarcolemma, and myofibril.

- The Muscle Belly: The outermost layer of connective tissue that surrounds the entire muscle.

- Epimysium: The outermost layer of connective tissue that surrounds the entire muscle.

- Perimysium: The connective tissue layer that surrounds bundles of muscle fibres.

- Fascicle: A bundle of skeletal muscle fibres.

- Endomysium: The thin connective tissue that surrounds each individual muscle fibre.

- The Muscle Fibre: A bundle of myofibrils.

- Sarcolemma: The muscle fibre membrane.

- Myofibrils: Fod-like structures composed of repeating sarcomeres that contain contractile elements.

Sarcomeres & Sliding Filament Theory

The sarcomere is the smallest contractile unit within skeletal muscle and is the reason we are able to shorten and lengthen our muscles. How movement happens is explained through the Sliding Filament Theory. But before we dive into how movement happens, we need to understand the components that make it happen. Using the diagram of a sarcomere below, follow along as each component is discussed.

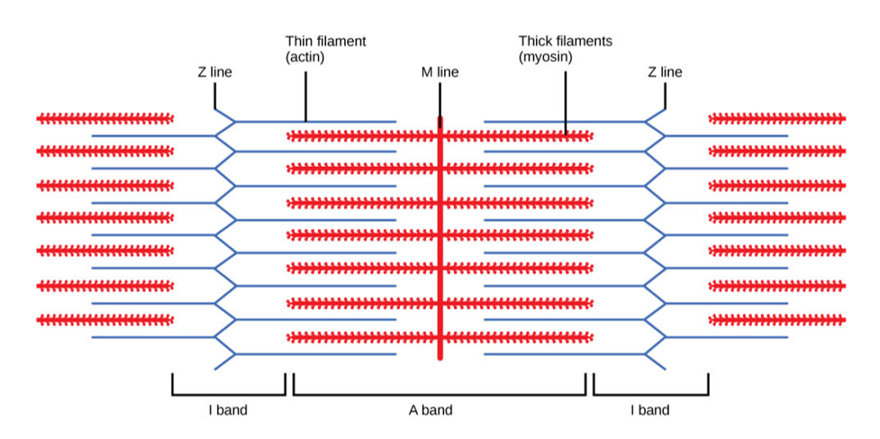

The illustration below is representative of a sarcomere, and therefore a muscle, at resting length. Each sarcomere begins and ends at the Z line, with its center point being the M line located in the middle. Several rows of two types of contractile filaments create the key components of the sarcomere. These are Actin, the thin filament, and Myosin, the thick filament. Both filaments are positioned in a highly organized, alternating structure that enables a sliding interaction.

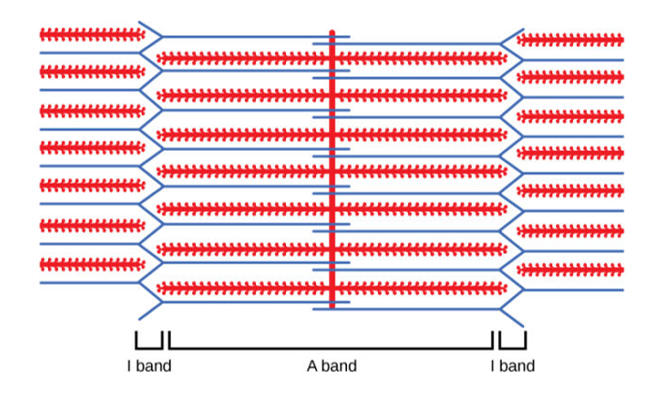

Contraction (or lengthening) occurs where the filament position changes, which therefore changes how much they overlap with one another. We measure if a muscle has contracted or lengthened by looking at the I and A bands indicated below. The A band represents the portion of the sarcomere where actin and myosin filaments overlap, while the I band represents where they do not, and only actin is present. When the sarcomere, and therefore the muscle, contracts, the A band increases in size while the I band decreases. However, when a muscle lengthens and the filaments overlap less, the A band decreases in size while the I band increases.

“10.1 Overview of Muscle Tissues” from Anatomy & Physiology by Lindsay M. Biga, Staci Bronson, Sierra Dawson, Amy Harwell, Robin Hopkins, Joel Kaufmann, Mike LeMaster, Philip Matern, Katie Morrison-Graham, Kristen Oja, Devon Quick, Jon Runyeon, OSU OERU & OpenStax is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International License, except where otherwise noted.