2 Sumer and the first civilizations

Cities and Civilization

The first civilizations formed on the banks of rivers. Cities, a new and transformational human environment, grew on the Nile, the Indus, the Yellow River in China, and on the Tigris and Euphrates in Mesopotamia. Rivers provided a steady supply of drinking water, rich sources of fish and good hunting spots. Rivers were also the most important ‘highways’ of the ancient world. Transport over land was slow, difficult and expensive even with pack animals, whereas riverboats could carry huge loads with relative ease. Sites on navigable rivers and near coasts were connected to a much wider world, for better and for worse; inland sites were by comparison isolated and inaccessible. Most importantly, soil eroded from inland was washed downstream and deposited into rich, fertile plains that supported dense crops. The first cities were founded on the bounty of these floodplains.

Archeologists and historians do not agree on what causes to credit for the emergence of these first cities: we will consider several. Cities could only emerge where there was productive enough agriculture to support them, and technological advances such as the plough may have enabled this. Shrines or sacred sites could have provided the kernel around which the first urban settlements coalesced, drawing together people from wide areas for festivals and rituals that increasingly evoked permanent occupations. The first cities were hubs of bureaucracy and administration, and centralised government works best in central locations. We have already seen how towns such as Çatalhöyük were early centres of crafts and trade. Seasonal or permanent markets also could draw people long distances and encourage craftsmen and others to settle nearby for the convenience of easy access to diverse wares. Finally, cities acted as refuges and protection from raids and warfare, even before but certainly after they erected fortresses and walls.

Cities were new environments, and human culture naturally adapts to new environments. Since cities themselves are culturally produced spaces, urban cultures reshape and in turn are reshaped by their urban environments. This process is transformative: urban cultures can change rapidly as cities grow, diversify, and become increasingly, intricately complex. Although every urban culture is unique, the similarities of their circumstances tend to produce some similar cultural traits. Historians classify a civilization as a culture with various key traits, all of which tend to or only ever emerge in urban cultures. These include:

Governments and states: civilizations develop institutions which exercise power over the community. This authority may be invested in kings, priests, councils, bureaucrats or popular assemblies, but regardless of the identity of the authorities, they govern with some degree of legitimacy — popular acceptance of their right to lead and make decisions — supported by some ability to mobilize force and violence. When a single government develops the ability to compel obedience to its decisions over a geographical area, we have a state. State authorities govern via a network of agents, often organised into a bureaucratic hierarchy. This underpins the ability of civilizations to act collectively at a large scale: to mobilize and coordinate thousands of people for important tasks such as public works and warfare.

Specialization: civilizations develop a complex set of interlocking social roles, many of which involved special skills that become vocations for people. The non-food producing roles are supported by redistributing food from farmers and other producers. Specialized roles that are found in even the earliest civilizations include craftspeople, merchants, priests, kings, bureaucrats, entertainers, teachers, soldiers, manual laborers, builders, and intellectuals.

Writing: civilizations consistently develop writing independently, and no other cultures develop writing without at least getting the idea from civilizations. Writing is a crucial technology, both for the civilizations themselves and for our understanding of them. Writing provides the main window through which we can see the past, and for this reason we know much more about ancient civilizations than their non-literate neighbours. But more importantly, writing fundamentally transformed civilizations themselves, allowing knowledge to be transmitted across time and space without having to be passed on through learning and memory. This formed the basis of new culture in a plethora of areas, from poetry and literature, to record-keeping and administration, to philosophy, religion, and eventually science. All of these aspects of culture are very different or entirely impossible without the invention of writing.

Warfare: the large-scale organized violence we call warfare originated with civilization and was intimately intertwined with it. Warfare mobilizes large numbers of people into organised groups that succeed of fail together in violent struggle with other groups. The stakes of warfare are the highest possible. Defeat risks death, rape, impoverishment, enslavement or exile. Victory offers, along with status and wealth, the prospect of capturing land or subjugating nearby groups so as to exploit them and their land. Civilizations therefore organise themselves to generate military power for defence and, usually, aggression. Military power is based on the number of people that can be mobilized to fight, their motivation, and the organisation and equipment of the military forces. Over time, civilizations collectively adapt to generate increasing amounts of military power, in ways that deeply shape their culture. The role of the state in civilized societies is intimately entwined with warfare, with the state mobilizing armies and building fortifications, and the state government making decisions of war and peace.

The first Eurasian civilizations to emerge were those of Sumer and Egypt, followed somewhat later by the Harappans and Chinese. These early civilizations shared certain further characteristics that were strongly associated with civilizations up until modern times.

Monarchy: The government was in the hands of a single ruler, usually male, who controlled the military and almost always had important religious duties and authority. Kings served as lawgivers and bolstered their legitimacy by claiming to protect the weak, feed the hungry, and do other good works for society. Kingly legitimacy was supported by religion, tradition, propaganda, large-scale building projects, and the enforcement of justice and order. But the most distinctive aspect of kingly authority was their leadership of the military and their control over foreign policy and foreign relations: they served as the ‘head’ of their people, acting as the voice and face of the collective group. Rulership was hereditary and passed down from father to a chosen son when possible. Women sometimes took on kingly power, either as regents or reigning queens. It is possible that the Harappans were not ruled by kings, and some Sumerian city states early on may have been ruled by councils or priests; priests of major temples also ruled parts of Egypt when central government fractured. We will also see some important later civilizations that were not ruled by kings, such as Rome, Carthage and Athens. But monarchies were the standard type of government in premodern civilizations.

Hereditary Stratification: The population was divided into groups that had different social statuses that they inherited from their family, which was normally bolstered by inherited wealth. The term for the privileged hereditary group is aristocracy; the exact nature of the aristocracy and the gradations of status within a civilization were very diverse. Sometimes very complex and formal hereditary systems developed with multiple different groups, most famously the caste systems of India; in other cases there was little formal distinction between aristocrats and other free people and the main difference was one of wealth and informal status barriers, such as we find in later Rome.

Slavery: We find the first clear evidence of slavery emerging with civilization, and most civilizations in premodern times engaged in slavery. The status, economic importance and treatment of slaves varied, but there were generally two main ways people could become enslaved: capture and debt. The losers in wars were often enslaved, and people who could not pay off their debts were sometimes forced to work those debts off via temporary or permanent enslavement, or by selling family members into slavery. Slavery was in premodern times not generally connected with race. The historical development of racialized slavery happened in early modern times as a result of overseas colonization and plantation economics.

Empire: states eventually developed the ability to subjugate and administer increasingly large areas whose populations were not willingly obedient, forming empires. This rule was imposed by force and maintained by bureaucracy, garrisons and propaganda. The growth of empires also extended the cultural and political reach of civilizations, bringing their language, laws, and religion to their imperial subjects. Given time, some empires managed to integrate their subject populations, while others ruled large populations of indifferent or hostile people. We will discuss empires further in the next chapter.

Mesopotamia

Between two rivers

Mesopotamia is a region in present-day Iraq. The word Mesopotamia is Greek, meaning “between the rivers,” and it names the area between the Tigris and Euphrates, two major rivers that flow from the southwest Asian highlands down to the Persian gulf. Mesopotamia’s climate six thousand years ago was much more temperate and moist than it is today. Mesopotamia was once a grassland that could support both large herds of animals and abundant crops. It was therefore well suited to support dense populations once farming and irrigation became established.

While the Tigris and Euphrates provided abundant water, they were highly unpredictable and sometimes swelled into huge floods, with disastrous consequences for people nearby. The southern region of Mesopotamia, Sumer, has an elevation decline of only 50 meters over about 500 kilometers of distance, meaning the riverbeds of both rivers could easily shift and meander. Over time, the inhabitants of villages worked together to build levees, canals, and dikes to protect against the floods and to channel water to their crops. The first governments in Sumer might have begun partly to organise, mobilize and feed the workers needed for these increasingly huge projects.

The first settlements that straddled the line between “towns” and real “cities” existed around 4000 BCE, but a truly urban society in Mesopotamia was in place closer 3000 BCE, when a few dozen city-states managed the waters of the Tigris and Euphrates. Remember that the town of Çatal Höyük discussed in chapter 1 existed over four thousand years before the first great cities in Mesopotamia. When considering ancient history it can seem like it everything happened quite rapidly, that people discovered agriculture and soon they were building massive cities and developing advanced technology. That is an understandable illusion: compared to the hundreds of thousands of years preceding the discovery of agriculture, things moved “quickly,” but from a human perspective these developments were very gradual indeed.

Sumerian City-States

As these cities expanded, their leaders claimed control over adjacent territories, forming at least a dozen city-states, which became the basic structure of Sumerian civilization in the third millennium BCE. City-states include a densely populated agricultural area surrounding a city that acts as the centre of politics, religion and trade for the local region. Despite the prominence of the city and the status of the inhabitants, most of the population is made up of the peasant farmers who either live in small towns nearby or within the city walls, walking out to their fields each day.

Sumerian cities had certain characteristics in common. First, a temple complex or a ziggurat was the heart of the city. Sumerians believed that their entire city belonged to its main deity, and built a massive temple, the most important building in the city, to be the dwelling place of their city’s main god or goddess. A building complex surrounded each temple that comfortably housed many of the priests and priestesses who served the city’s deity . In addition to attending to the religious needs of the community, temple complexes also owned land, managed industries, were involved in trade, and acted as banks. Their wide-ranging roles meant that temples often had additional outbuildings, like granaries and storage sheds, in the surrounding countryside. Sumerians were polytheistic, meaning they worshipped multiple gods and goddesses. Because Sumerians believed each god had a family, they also built smaller shrines and temples dedicated to these divine family members. Therefore, each city would have a number of temples while many Sumerian homes had small altars dedicated to other gods.

Sometimes, Sumerian temples or ritual spaces were built atop a ziggurat, a solid rectangular tower made of sun-dried mud bricks. Archaeological evidence shows that temple complexes were expanded and rebuilt over time and, by the late third millennium BCE, temples in many of the Sumerian city-states were raised on platforms or else situated on a ziggurat. The towering architecture of the ziggurat stressed the significance of the temple to the surrounding community. The best-preserved ziggurat, the Great Ziggurat of Ur, was constructed with an estimated 720,000 baked bricks and rose to a height of about 100 feet. The people of Ur constructed this ziggurat for their patron deity, the moon goddess Nanna.

Society

Viewing nature as unpredictable, people throughout Sumer brought offerings to their city’s temple complexes or ziggurat, hoping to please the gods who controlled the natural forces of their world. Priests and priestesses collected and redistributed the offerings, serving as the basis for the redistributive economy that allowed many Sumerians to take on a variety of non-food producing occupations. The relatively privileged position of priests and priestesses at the temple complex put them near the top of Sumerian social stratification as it developed. Some of the early leaders of Sumerian cities may have been “priest-kings,” who attained elevated positions through their association with the temples. The later rulers of city-states supported the temples, claiming to be acting on behalf of the gods who brought divine favor to their followers. Over time, the temples became centres that collected formal taxes that were paid out as salaries to priests, bureaucrats and manual laborers.

Sumerian city-states had local rulers, who lived in large palaces, but most of these local rulers were not considered kings, which in the Sumerian king list meant a ruler of two or more cities. So far, archeologists have dated the earliest known royal palaces to c. 2600 BCE and conclude that Sumerian city-states had centralized governments with secular rulers by at least that timeframe.

1.1 The “Urukean expansion,” a period in the fourth millennium BCE in which Sumerian material culture (and presumably Sumerian people) spread hundreds of miles from Sumer itself.

Social stratification is further evident as some Sumerians and even institutions, including temples, owned slaves. Slaves performed a variety of tasks like construction, weaving, agricultural and domestic labor, tending animals, and even administrative work as scribes. Some slaves were chattel slaves, meaning that society treated them as property with no rights. Usually, chattel slaves were prisoners of war or slaves bought from outside communities. They were branded by barbers or tattoo artists and forced to work at the will of their masters. If they tried to run away, the law required slaves to be returned. The more widespread type of servitude in Sumerian cities was likely debt slavery, which was generally temporary until a debtor paid off a loan and its interest. Over the past century or so, archaeologists have added a great deal to our understanding of Sumerian social distinctions through their work at numerous excavation sites, but many gaps in our knowledge still exist.

Legal documents and tax records show that people owned property in both the cities and the countryside. Some Sumerians owned fairly large chunks of land, while others had much smaller plots or no land at all. Wills, court proceedings, and temple documents show that land and temple offices were usually bought or else acquired through military or other service to the state. A man inherited land, property, offices, and their attendant obligations to the state (like reoccurring military service) from his father. The eldest son seems to have frequently inherited a larger share than younger brothers and have been given control over the family home. He was tasked with performing regular rituals to honor dead ancestors, who were usually buried underneath the home. From the written documents, we also get glimpses into other aspects of Sumerian life, like marriage and divorce.

Sumerians viewed marriage as a contract between two families and, as a result, the male heads of the two families arranged a couple’s marriage. Documents show that both families contributed resources to seal the union or complete the marriage contract. The man’s family gave gifts or money and hosted a feast, while the woman’s family amassed a dowry, wealth that was given to the couple for their household use. Although a woman did not automatically receive an inheritance upon the death of her father, she could expect (and use the court system to make sure she got) to receive a dowry, even if it came from her father’s estate after his death. Divorce was possible but sometimes led to social ostracism or even punishment if there were accusations of misconduct, such consequences being especially the case for the woman. Records indicate that polygamy was not common, but wealthier men did keep slave-girls as concubines. Overall, Sumerians considered marriage an essential institution in that it brought families together and ensured the continuation of the family lineage.

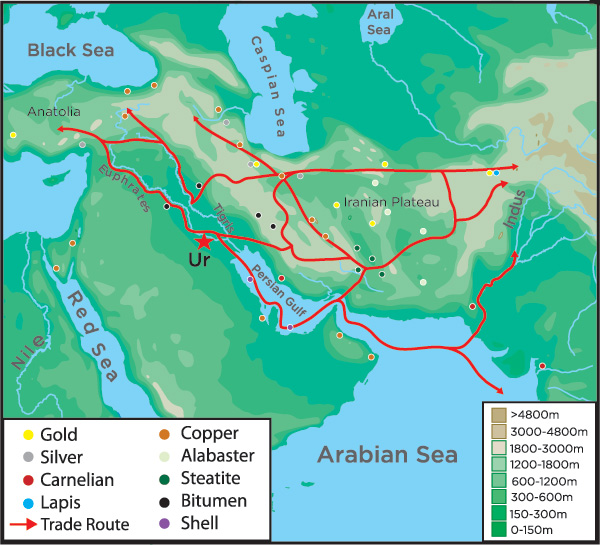

The Sumerian cities’ location on huge, navigable rivers facilitated trade. Sumer had abundant food, cloth and mud (which they baked into bricks and built with), but lacked wood, stone and metals such as copper. Traders were able to use the rivers to bring in these resources from Assyria, Anatolia, the Levant, and the Persian Gulf coast. Early Mesopotamians also obtained goods from the Harappan civilization that emerged on the banks of the Indus river. Merchants used overland routes that crossed the Iranian Plateau and sea routes, exchanging Mesopotamian products like grains and textiles for luxury goods from the east. Royal cemeteries show that by 2500 BCE Mesopotamian elites were buried with a variety of imports, including beads brought from the Indus River Valley. The rivers and the overland trade routes also facilitated communication and, with it, the sharing of ideas and technologies.

A complaint letter from a merchant

The letters of Sumerian merchants offer our first written evidence of long-distance trade, the networks of which spanned thousands of kilometers in Sumer’s day and which eventually expanded to encompass first the Eurasian continent, and eventually the globe. Their concerns and interests are very relatable to our modern, commercial civilization, discussing prices, debts, taxes and even schemes to evade customs duties. Writing again was a key technology, allowing merchants to write letters to co-ordinate shipments and sales via trusted agents in far-off cities, often relying on ties of blood or marriage to discourage fraud and theft. Sumerian merchants provided essential services because of Sumer’s lack of vital raw materials: while they dealt in high value luxuries such as semi-precious stones, their core business was trading food and textiles for wood, stone, and metal. Transport relied on rafts, barges, donkey teams, and ocean-going sailing ships built from bushels of reeds.

Writing and Learning

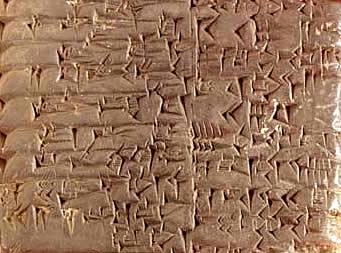

The Mesopotamians invented the first systems of writing, developed in order to keep track of tax records sometime around 3000 BCE. Their style of writing is called cuneiform; it started out as a pictographic system in which each word or idea was represented by a symbol, but it eventually changed to include both pictographs and syllabic symbols (i.e. symbols that represent a sound instead of a word). While it was originally used just for record-keeping, writing soon evolved into the creation of true forms of literature. As the importance of writing in the society grew, a new social role, the scribe, emerged. Scribes studied in schools to master reading and writing, and some of the worksheets that they completed for their teachers have survived to this day. An education could open doors to a job in the temple bureaucracy, whether as a lowly record keeper or as a powerful overseer. And while most of the writings of scribe were utilitarian records of taxes and debts, the new technology opened the possibility of written literature.

1.3 An example of cuneiform script, carved into a stone tablet, dating from c. 2400 BCE.

The first known author in history whose name and some of whose works survive was a Sumerian high priestess, Enheduanna. Daughter of the great conqueror Sargon of Akkad (described below), Enheduanna served as the high priestess of the goddess Innana and the god of the moon, Nanna, in the city of Ur after its conquest by Sargon’s forces. Enheduanna wrote a series of hymns to the gods that established her as the earliest poet in recorded history, praising Innana and, at one point, asking for the aid of the gods during a period of political turmoil.

A Hymn by Enheduanna

O house

wrapped in beams of light

wearing shining stone jewels

wakening great awe

sanctuary of pure Inanna

(where) divine powers the true me spread wide

Zabalam

shrine of the shining mountain

shrine that welcomes the morning light

she makes resound with desire

the Holy Woman grounds your hallowed chamber

with desire

your queen

Inanna of the sheepfold

that singular woman

the unique one

who speaks hateful words to the wicked

who moves among the bright shining things

who goes against rebel lands

and at twilight makes the firmament beautiful

all on her own

great daughter of Suen

pure Inanna

O house of Zabalam

has built this house on your radiant site

and placed her seat upon your dais

Enheduanna did not record the first known work of prose, however, whose author or authors remain unknown. Remembered as The Epic of Gilgamesh, the earliest surviving work of literature, it is the best known of the surviving Mesopotamian stories. The Epic describes the adventures of a partly-divine king of the city of Uruk, Gilgamesh, who is joined by his friend Enkidu as they fight monsters, build great works, and celebrate their own power and greatness. Enkidu is punished by the gods for their arrogance and he dies. Gilgamesh, grief-stricken, goes in search of immortality when he realizes that he, too, will someday die. In the end, immortality is taken from him by a serpent, and humbled, he returns to Uruk a wiser, better king.

Like Enheduanna’s hymns, which reveal at times her own personality and concerns, The Epic of Gilgamesh is a fascinating story in that it speaks to a very sophisticated and recognizable set of issues: the qualities that make a good leader, human failings and frailty, the power and importance of friendship, and the unfairness of fate. Likewise, a central focus of the epic is Gilgamesh’s quest for immortality when he confronts the absurdity of death. Death’s seeming unfairness is a distinctly philosophical concern that demonstrates a sophisticated engagement with the human condition present in Mesopotamian society.

The Mesopotamians were the first great astronomers, accurately mapping the movement of the stars and recording them in star charts. As seen in the case of both ziggurats and irrigation systems, they were excellent engineers. They also invented the 360 degrees used to measure angles in geometry and they were the first to divide a system of timekeeping that used a 60-second minute, both relics of their number system that was based around multiples of 60. Finally, they developed a complex and accurate system of arithmetic that would go on to form the basis of mathematics as it was used and understood throughout the ancient Mediterranean world.

At the same time, the Mesopotamians employed many “magical” practices. The priests did not just conduct sacrifices to the gods, they developed techniques of divination to predict future events. The modern distinction between magic and science does not often apply well to the practices of the premodern past. The sophisticated understanding of the planets and seasons used by Sumerian astronomers were intertwined with their beliefs about the world and the gods. In trying to learn about how the universe functioned so that human beings could influence it more effectively, ancient ‘scientists’ did not conceive of nature as a material machine or as governed by unchangeable laws. From the perspective of the ancient Mesopotamians, there was little that distinguished religious and magical practices from “real” science in the modern sense. Their observations and accomplishments that we see as scientific were embedded in and motivated by a belief system that included religious and magical ideas.

War and Empire

Mesopotamia represents the earliest indications of large-scale warfare. Mesopotamian cities had walls from very early on – some of which were 30 feet high and 60 feet wide, enormous ramparts of earth strengthened by brick. The evidence (based on pictures and inscriptions) suggests that most soldiers were peasant militia armed with shields and spears or bows. Militia are ordinary citizens who have a social responsibility to fight for their state during wars. They are therefore part-time soldiers, whose effectiveness depends on their cultural willingness to fight and on how often they get experience training and fighting. Some militia armies are amateurish and unreliable, but some of the most effective premodern armies were motivated and experienced militias, such as those of the Roman republic or of the Greek city-states in the classical period. One advantage of militia armies is that they can mobilize very large numbers of fighting men, but only for short periods before their absence cripples the economy. For short wars between neighbours within a few days walk such as those of the Sumerian city-states, militia can be very effective, so long as they are motivated to fight hard for their leaders.

Sumerian kings may have had bodyguards of more professional ‘companions’, and popular councils may have played a role in authorizing or mobilizing the men for war. If so, such popular involvement in warmaking decisions would help ensure that the militia making up the army were motivated and supportive of the conflict, and therefore reliable on the battlefield.

While little evidence survives, Sumerian warfare likely revolved around the two constants of conflict between city states: field battles to steal or destroy the enemy’s harvest, and sieges and assaults on the enemy’s fortified city. Cities during the third millenium BCE warred on one another for territory, captives, and riches, but they rarely succeeded in conquering other cities outright, and when they did, the dominance did not typically last. Kings, after all, could not be in two places at once, and sooner or later a city would find an opportunity to close its gates and rid itself of hated foreign governors. The situation may have been similar to the much better documented world of the classical Greek city states, which we look at in chapter 4.

The first time that a single military leader managed to conquer and unite many of the Mesopotamian cities was in about 2340 BCE, when the king Sargon the Great, also known as Sargon of Akkad (father of Enheduanna, described above), conquered almost all of the major Mesopotamian cities and forged the region’s first empire, in the process uniting the regions of Akkad and Sumer. His empire appears to have held together for about another century, until somewhere around 2200 BCE. Sargon also may have created the world’s first standing army, a group of soldiers employed by the state who did not have other jobs or duties. One inscription claims that “5,400 soldiers ate daily in his palace,” and there are pictures not only of soldiers, but of siege weapons and mining (digging under the walls of enemy fortifications to cause them to collapse). As we will discuss in the next chapter, long-distance campaigns of conquest are difficult to conduct with militia armies, so Sargon’s success in creating the first Mesopotamian empire may have been connected to the use of professional soldiers. We will discuss empires and conquest in more detail in the next chapter.

1.4 The expansion of Sargon’s empire, which eventually stretched from present-day Lebanon to Sumer.

Sargon himself was born an illegitimate child who, according to the tale that survives, was abandoned in a basket that was floated down the river until the baby was rescued by a welcoming family. He eventually became a royal gardener who worked his way up in the palace, eventually seizing power in a coup. He boasted about his lowly origins and claimed to protect and aid common people and merchants. Sargon appointed governors in his conquered cities, and his whole empire was designed to extract wealth from all of its cities and farmlands and pump it back to the capital of Akkad, which he built somewhere near present-day Baghdad. While his descendants did their best to hold on to power, the resentment of the subject cities eventually resulted in the empire’s collapse.

The next major Mesopotamian empire was the “Ur III” dynasty, named after the city-state of Ur which served as its capital and founded in about 2112 BCE. Just as Sargon had, the king Ur-Nammu conquered and united most of the city-states of Mesopotamia. The most important historical legacy of the Ur III dynasty was its complex system of bureaucracy, which was more effective in governing the conquered cities than Sargon’s rule had been.

Technologies: Bureacracy

Bureaucracy (which literally means “rule by office”) is perhaps one of the more underappreciated phenomena in history. But there is no more efficient way yet invented to manage large groups of people: it is viable to coordinate small groups through the personal control and influence of a few individuals, but as cities grew and empires formed, it became less practical to base government on personal relationships. An efficient bureaucracy, one in which the individual people who were part of it were less important than the system itself (i.e. its rules, its records, and its chain of command), allows human groups to create a system tailored to accomplish specific tasks, that does not rely on relationships that will die with their mortal creators.

Feeding armies, building walls, canals and palaces, collecting taxes, and communicate information all rely on the existence of reliable systems to accomplish these complex and difficult tasks. Bureacracies create routines that do this, by identifying tasks, delegating resources, transferring information, and making decisions. Writing plays a central role, enabling record keeping and allowing actions to be co-ordinated through time and space via letters, guidelines and memoranda. Government bureaucracies were therefore the first human institutions where literacy and formal education became essential, setting the stage for much greater diversity in intellectual and academic vocations to come.

The Ur III dynasty is an example of an early bureaucratic empire. Historians have more records of this dynasty than any other from this period of ancient Mesopotamia thanks to its focus on codifying its regulations. The kings of Ur III were very adept at playing off their civic and military leaders against each other, appointing generals to direct troops in other cities and making sure that each governor’s power relied on his loyalty to the king. The administration of the Ur III dynasty divided the empire into three distinct tax regions, and its tax bureaucracy collected wealth without alienating the conquered peoples as much as Sargon and his descendants had (despite its relative success, Ur III, too, eventually collapsed, although it was due to a foreign invasion rather than an internal revolt).

From Old Babylon to the Medes

When Sargon of Akkad built Mesopotamia’s first empire around 2300 BCE, he inaugurated a new era in the Near East. Though it lasted only about a century and a half, his model of imperial expansion and administration was followed by a number of successive powers in the region. The Third Dynasty of Ur and Hammurabi’s Babylonian kingdom were in many ways imitators of Sargon’s earlier example. Later powers like the Hittites, Neo-Assyrians, and Neo-Babylonians continued to borrow from earlier empires and added unique traits as well.

The city of Babylon, unlike Ur, had not previously been an important city-state. Akkadian-speakers called it Bab-ili, which meant “gateway of the gods.” In 1894 BCE, an Amorite chieftain named Sumu-adum took the city and installed himself as ruler. His successors expanded their control over the surrounding area, building public works projects and digging canals. But this expansion was modest, and by about 1800 BCE, Babylon controlled only a relatively small territory around the city itself. Indeed, at this time, it was just one of a handful of small states making up a loose coalition in Mesopotamia.

It was during the reign of Hammurabi in eighteenth century BCE that Babylon rose as a center of power and the administrative capital of a new Mesopotamian empire. Early in his reign, Hammurabi made an alliance with the powerful Assyrians to the north. This pact gave him the protection he needed to expand his kingdom, taking control of Isin, Uruk, and other key cities of southern Mesopotamia. Soon Babylon had become a major center of power in the south and the target of rival kingdoms. In approximately 1764 BCE, a coalition of city-states invaded Babylonian territory, hoping to capture Hammurabi’s powerful realm, but it failed, and Hammurabi turned his military attention to the south. Eventually, he sent his armies even against his former ally, Assyria. By 1755 BCE, he had transformed the small kingdom he inherited into the center of a Mesopotamian empire to rival any that had come before it.

At its height during Hammurabi’s reign, the Babylonian Empire stretched from the upper reaches of the Euphrates River, not far from modern Aleppo in the north, to the Zagros Mountains in the east and the Persian Gulf in the south. But these extensive borders did not long survive the death of Hammurabi himself. Under the rule of his son Samsu-iluna, Babylon faced increasing resistance from surrounding peoples. The empire’s territorial control continued to decline until, by late sixteenth century BCE, all that remained was the small region around the city of Babylon itself. In this weakened state, Babylon was sacked by a new emerging power, the Hittites, and the dynasty of Hammurabi came to a definitive end.

Unlike the Babylonians, the Hittites were not from Mesopotamia. Rather, they were an Indo-European-speaking group that emerged as a powerful force in Anatolia starting in the 1600s BCE. Their precise origins are not known, but by 1650 BCE, the Hittites dominated central Anatolia from their capital at Hattusas. Their expansion across Anatolia and into Syria continued into the early sixteenth century BCE when the growing kingdom set its sights on Babylon. Possibly as a demonstration of military might or simply to seize an opportunity, the Hittite army descended into Mesopotamia and took the city of Babylon.

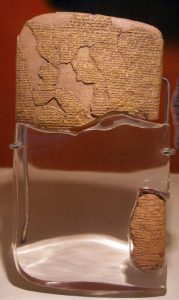

By the mid-fourteenth century BCE, the Hittites had become arguably the most powerful empire in the Near East and a major rival of New Kingdom Egypt. The two realms vied for control of the eastern Mediterranean in the 1300s and 1200s BCE, eventually facing off in the epic Battle of Qadesh in 1274 BCE. Generally accepted as a draw or possibly a narrow Hittite victory, the fighting at Qadesh is most memorable for ultimately leading the two forces to recognize that they had more to gain from peace than war. In 1258 BCE, the Hittite king Hattusilis II and the Egyptian Pharaoh Ramesses II signed one of early history’s greatest peace treaties. The agreement confirmed Hittite control of Syria and Egyptian dominance over the Phoenician ports of the eastern Mediterranean. However, little more than fifty years later, the once-powerful Hittite Empire collapsed, never to reappear.

The Hittite Empire was not the only important Near Eastern power to disintegrate during this period. Across the eastern Mediterranean and Mesopotamia beginning around 1200 BCE, kingdoms and empires from Greece to Mesopotamia went into a decline so extensive it is now called the Late Bronze Age Collapse. Although its trigger remains unknown, the collapse coincided with widespread regional famine, epidemic disease, war, and waves of destructive migrations across the eastern Mediterranean. By the time calm returned around 1100 BCE, the region had entered a new era, the Iron Age. This was a period in which iron replaced bronze as the metal of choice for tools and weapons, and new and more sophisticated empires expanded across the Near East.

For a few centuries after the Late Bronze Age Collapse, Mesopotamia experienced transformations that dramatically reshaped the region and set the stage for a new imperial era. During the eleventh and tenth centuries BCE, decline came to both Assyria and especially to Babylonia, where dynasties competed for control.

It was only around 900 BCE that Assyria was able to reestablish control over northern Mesopotamia. This marks the birth of what historians often refer to as the Neo-Assyrian Empire (to distinguish it from the Old Assyrian Empire of 2000–1600 BCE and the Middle Assyrian Empire of 1400–1100 BCE). The Assyrians themselves did not refer to this phase of their empire as Neo-Assyrian but regarded it as simply another development in their history.

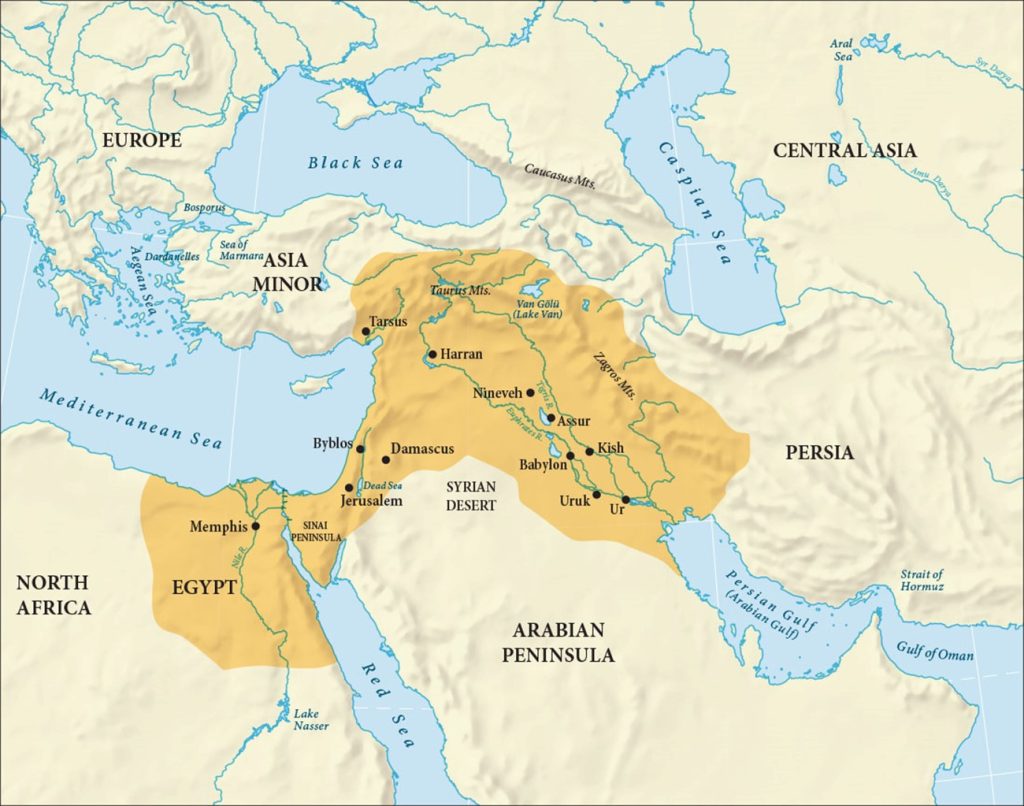

The Neo-Assyrian Empire (912-612 BCE) was the final stage of the Assyrian Empire, stretching throughout Mesopotamia, the Levant, Egypt, Anatolia, and into parts of Persia and Arabia. Beginning with the reign of Adad Nirari II (912-891 BCE), the Neo-Assyrian kings made great territorial expansions to forge the greatest empire that had existed up to that time. By the end of Tiglath-Pileser III’s reign in 727 BCE, the Neo-Assyrian Empire had become the dominant power in the Near East.

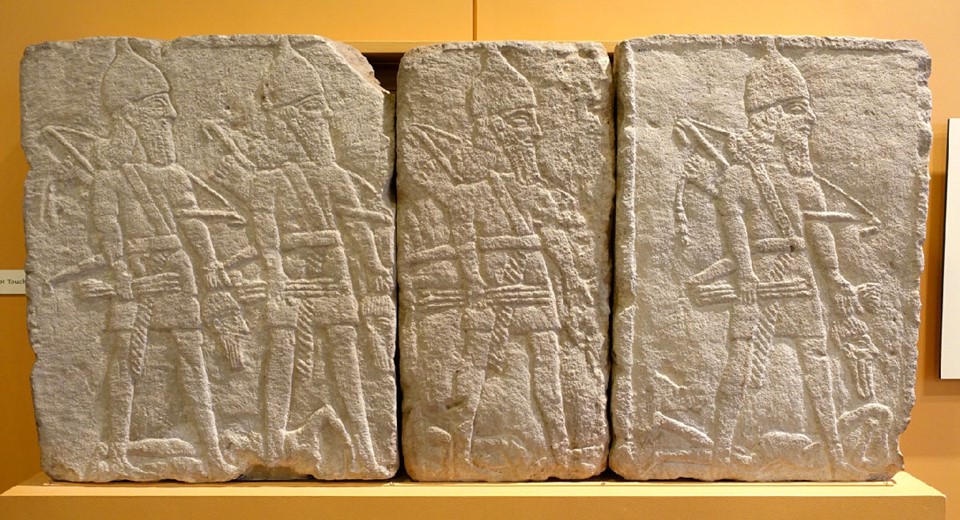

The constant wars of conquest undertaken during the Neo-Assyrian Empire necessitated a highly skilled and well-organized standing army. The Assyrians fielded the most effective fighting force in the world, the first to be armed with iron weapons, and whose tactics in battle made them invincible. This army included charioteers, cavalry, archers, and wielders of slings and spears. All Assyrian men were expected to serve some period of military service. The king was the official head of the army, and his chief officials were high-ranking military officers. The Neo-Assyrian Empire was effectively a military state, and it was demonstrably efficient at expanding its territory and keeping its vassals in line.

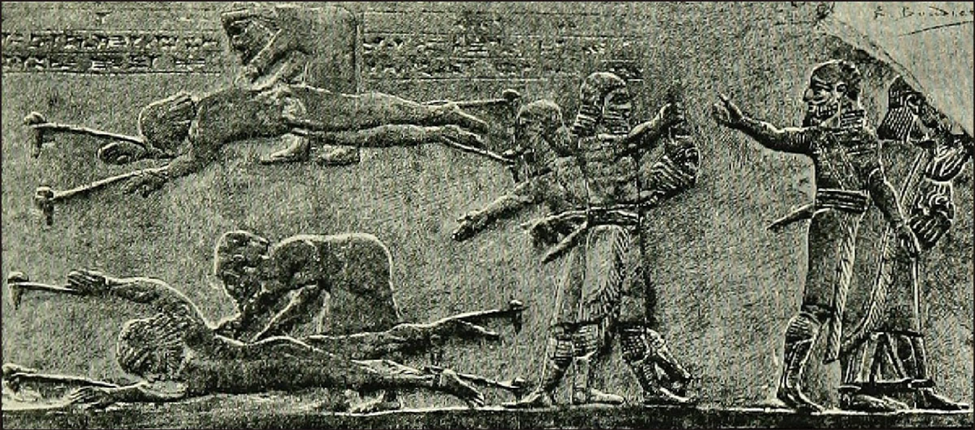

Their political and military policies have also given them the long-standing reputation for cruelty and ruthlessness though this has come to be challenged in recent years, as it is now argued they were neither more nor less cruel than other ancient empires such as that of Alexander the Great or of Rome. That said, this reputation was actively cultivated by the Assyrians, as part of their war strategy. Those who defied the Assyrian war machine could expect swift and devastating consequences, including public torture and mutilation to demonstrate the price of rebellion – a response that scholars have called “calculated frightfulness”. Though mighty, the Neo-Assyrians tried to avoid warfare, usually by demanding a besieged city surrender without a fight. But if forced, they used “calculated frightfulness” to demonstrate the price of resistance, inflicting various forms of torture on the conquered peoples.

Another tactic to shut down regular or particularly difficult rebellions was the forced deportation of entire populations to other parts of the empire. The elite and skilled in a city were compelled to move to a previously depopulated region, there to be steadily assimilated into the surrounding culture until they became culturally indistinguishable from other Assyrians, thus dissipating any possibility of rebellion.

Over the next several decades, successive Assyrian kings were able to build an expansive empire across Mesopotamia and the eastern Mediterranean through wars of conquest. In 671 BCE, King Esarhaddon invaded Egypt and added that center of wealth and power to his kingdom.

With this conquest, the Neo-Assyrian Empire achieved a degree of territorial control far surpassing that of any earlier empire of the region. But its supremacy was not to last. Beginning in the last decades of the seventh century BCE, two growing powers threatened and eventually overthrew Assyria. These kingdoms were Babylonia and Media, the kingdom of the Medes.

During the period of Assyrian expansion, Babylonia had been reduced to a vassal state of the empire, meaning it was nominally independent in the running of its internal affairs but had to bow to imperial demands and provide goods and soldiers when commanded. But in 616 BCE, the Chaldean Babylonian ruler Nabopolassar attempted to take advantage of a period of Assyrian weakness by launching a bold attack against the Old Assyrian capital of Asshur.

Although the attack failed, it encouraged the Median dynasty to risk its own attack into Assyria. The attack by the Medes on Assyria proved successful, and Asshur was destroyed in 614 BCE. Shortly afterward, the Babylonians and the Medes entered into an alliance to overthrow Assyria. Assyria received support from Egypt, but it was unable to prevent the Babylonian-Median alliance from overwhelming its forces and capturing its cities. In 612 BCE Nineveh was sacked and burned and the Assyrian king killed, by a coalition of Babylonians, Persians, Medes, among others. The destruction of the great Assyrian cities was so complete that, within two generations of the empire’s fall, no one knew where the cities had been. The ruins of Nineveh were covered by the sands and lay buried for the next 2,000 years.

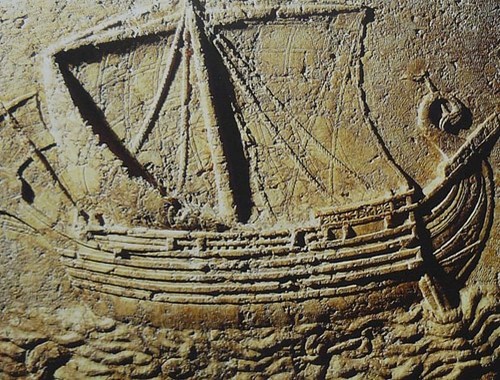

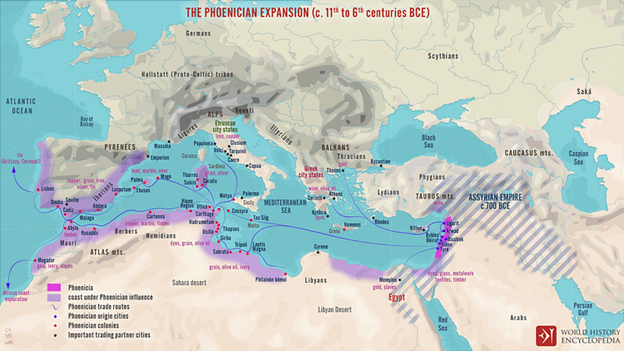

The Assyrians and other civilizations during this time were variously distinguished in war and conquest. Another civilization in the region, the Phoenicians, were distinguished in different ways. Phoenicia was an ancient civilization composed of independent city-states located along the coast of the Mediterranean Sea stretching through what is now Syria, Lebanon and northern Israel. The Phoenicians were a great maritime people, known for their mighty ships adorned with horses’ heads in honor of their god of the sea.

Phoenician city-states began to take form c. 3200 BCE and were firmly established by c. 2750 BCE. Phoenicia thrived as a maritime trader and manufacturing center from c. 1500-332 BCE and was highly regarded for their skills in ship-building, glass-making, the production of dyes, and an impressive level of skill in the manufacture of luxury and common goods.

The purple dye manufactured and used in Tyre for the robes of Mesopotamian royalty gave Phoenicia the name by which we know it today (from the Greek Phoinikes for Tyrian Purple) and also accounts for the Phoenicians being known as ‘purple people’ by the Greeks, as the Greek historian Herodotus tells us, because the dye would stain the skin of the workers.

Phoenician purple became the standard adornment of royalty from Mesopotamia, through Egypt, and up through the ruling elites of the Roman Empire. All of this was accomplished as a result of the competition between the city-states of the region, the skill of the sailors who transported the goods by navigating the often turbulent waters of the Mediterranean Sea, and the high art attained by the craftsmen in the manufacture of the goods.

The competition was particularly keen between the cities of Sidon and Tyre, arguably the most famous of the city-states of Phoenicia who, along with the merchants of Byblos, carried and transmitted the cultural beliefs and societal norms of the nations they traded with to each other. The Phoenicians, in fact, have been called the `ancient middlemen’ of culture by many scholars and historians because of their role in cultural transference.

In its time Phoenicia was known as Canaan and is the land referenced in the Hebrew Scriptures.

Herodotus cites Phoenicia as the birthplace of the alphabet, stating that it was brought to Greece from Phoenicia sometime before the 8th century BCE, and that the Greeks had no alphabet prior to this. The Phoenician alphabet also is the basis for most western languages written today.

There is no doubt regarding the popularity of the goods produced in Phoenicia. So extraordinary was the skill of the artists of Sidon in glass-making that it was thought the Sidonians invented glass. They provided the model for the Egyptian manufacture of faience (glazed earthenware) and set the standard for work in bronze and silver. Further, the Phoenicians seem to have developed the art of mass production in that similar artifacts, fashioned in the same way and in large quantities, have been found in the different regions with which the Phoenicians traded.

Because their goods were so highly prized, Phoenicia was often spared the kinds of military incursions suffered by other regions of the Near East explored in this chapter. For the most part, the great military powers preferred to leave the Phoenicians to their trade. Artifacts from the region have been found as far away as Britain and as close as Egypt, and it is clear that Phoenician luxury goods were highly prized by the cultures with whom they traded.

Eventually, in the 4th century BCE however, the cities of Phoenicia get caught up in Alexander the Great’s expansion of his empire. In his ruthless sacking of the great Phoenician city of Tyre in 332 BCE after a siege of several months duration, he breached Tyre’s walls and massacred most of the population, with many others sold into slavery. After the fall of Tyre, the other Phoenician city-states surrendered to Alexander’s rule, thus ending the Phoenician Civilization.

The Medes or Medians were major players in conflicts within the region as has been noted above. They were a group of Indo-Iranian-speaking people from central Asia who migrated westwards around the end of the 2nd millennium BCE. They settled in the highlands of Zagros (Zagreus in Greek) and, by the end of the 7th century BCE, founded the kingdom of Media. Since no written records of the migrating groups from Central Asia during the Late Bronze Age have been found, it is unclear by what name(s) they used to call themselves. Median (or Medes) was the Greek term applied much later. The Medians, however, were originally a group of North Zagros tribes or clans, which were in constant conflict with each other before their unification in the 8th century BCE, mainly to fight back the invasions of the Assyrians from the east and of the Urartians and Scythians from the north.

Median history is studied through two main groups of ancient sources that are not always consistent: Mesopotamian records (particularly Assyrian inscriptions) and historical writings (mainly Herodotus’ Histories, 1.95-106). Both, however, agree that the Medians were highly acclaimed horsemen and ruthless warriors, who not only secured their independence from the Neo-Assyrian Empire and other great powers of the region but went further and expanded their borders into the heartland of Mesopotamia, eastern Anatolia, and western Iran. The Median Empire became a superpower in 612 BCE, following its contribution to the downfall of the Neo-Assyrian Empire.

Within decades, though, after the defeat of the last Median king by Persian king Cyrus II and the fall of Ecbatana in 549 BCE, Media was no longer an independent and leading kingdom and came under Persian rule. Although their kingdom did not last long, the Medians left a deep and strong impression on their contemporaries. Median heritage lived on through their profound impact on the ancient Persian culture.

The Mesopotamian region saw a series of empires that fought against, allied with, and influenced one another in a complex and ever shifting timeline of interconnection and transformation. While empires succeeded one another in Mesopotamia, another empire had arisen to the west, along the fertile banks of the sinuous Nile river. In the next chapter we will look at what empires are in more detail, using Egypt as our main example.

This chapter contains material from

Western Civilization: A Concise History by Christopher Brooks and is used under a CC BY-NC-SA license.

World History: Cultures, States and Societies to 1500 by Berger et. al. and is used under a CC BY-SA 4.0 license.

World History to 1700 by Rene L. M. Paredes and is used under a CC BY 4.0 license.

Media Attributions

1.1 Urukean Expansion Map by Sémhur, CC BY-SA 3.0

1.2 Maritime and Land Trade Routes in Sumer, from Ancient Mesapotamia: Uruk Period, copyright Penn Museum

1.3 Cuneiform by Salvor, in the public domain

1.4 Sargon Map by Nareklm is licensed under CC BY-SA 3.0

“A Letter from a Slave Girl” and “A Complaint Letter from a Merchant” are excerpted from Letters from Mesopotamia: Official Business, and Private Letters on Clay Tablets from Two Millennia by A. Leo Oppenheim, copyright University of Chicago Press

From Old Babylon to the Medes

This section compiled and adapted from

World History Encyclopedia: Neo-Assyrian Empire; Phoenicia; by Joshua L. Mark and used under a CC BY-NC-SA 4.0 license.

World History Encyclopedia: Medes – by Nathalie Choubineh and used under a CC BY-NC-SA 4.0 license.

World History Volume 1, to 1500: Section 4.1 From Old Babylon to the Medes by Ann Kordas, Ryan J. Lynch, Brooke Nelson, Julie Tatlock OpenStax and used under a CC BY 4.0 license.

Media Attributions for this section

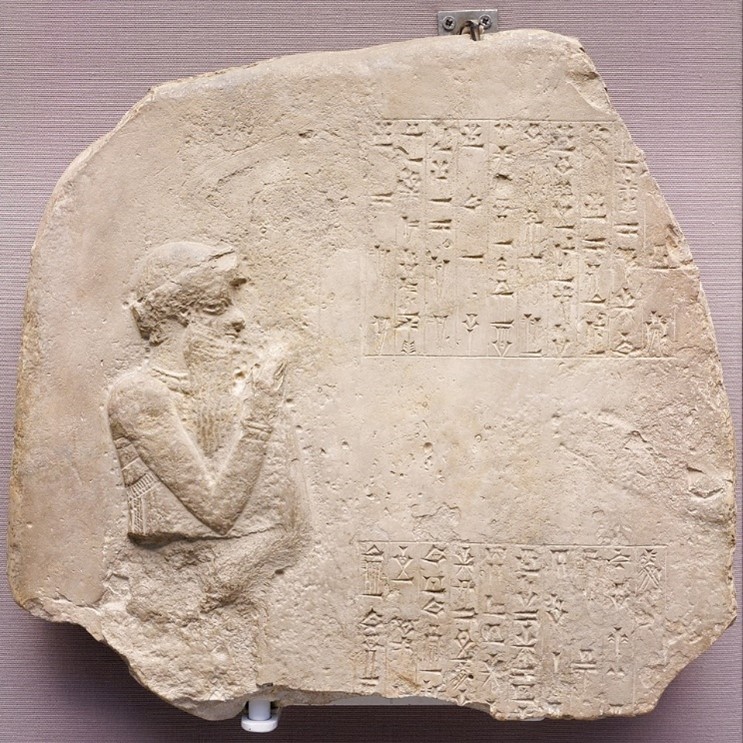

Hammurabi raising his arm in worship by Mary Lan-Nguyen and used under a CC-BY 2.5 license.

The Hittite Empire. Map Copyright Rice University, OpenStax, used under a CC BY 4.0 license.

The Egypto-Hittite Peace Treaty. Credit: “Treaty of Kadesh” by Iocanus used under a CC BY 3.0 license.

Assyrian Grooms and Horses 8th Century BCE, by Osama Shukir Muhammed Amin FRCP(Glasg) used under a CC-BY-SA 4.0 license.

The Victorious Assyrian Army. Credit: “Orthostats showing Assyrian soldiers, by Daderot used under a CC0 1.0 Public Domain license.

Resistance to Neo-Assyrian Rule. Credit: modification of work “Image from page 248 of ‘History of Egypt, Chaldea, Syria, Babylonia and Assyria’ (1903)” by Internet Archive Book Images/Flickr, used under a Public Domain license.

The Neo-Assyrian Empire. Map. Copyright Rice University, OpenStax, used under a CC BY SA 4.0 license.

Phoenician-Punic Ship by NMB used under a CC BY-SA license.

Phoenician Glassware by Remi Mathis used under a CC BY-SA license.

The Phoenician Expansion c. 11th to 6th centuries BCE by Simeon Netchev used under a CC BY-NC-ND license.

Media Attributions

- 4 Hammurabi Raising his Arm in Worship

- 4 The Hittite Empire

- 4 The Egypto-Hittite Peace Treaty

- 4 Assyrian Grooms and Horses

- 4 The Victorious Assyrian Army

- 4 Resistance to Neo-Assyrian Rule

- 4 The Neo-Assyrian Empire

- 4 Phoenician-Punic Ship

- 4 Phoenician Glassware

- 4 The Phoenician Expansion

Feedback/Errata