8 The Fall of the Republic and the Augustan Age

The End of the Republic

The Roman Republic lasted for roughly five centuries. It was under the Republic that Rome evolved from a single town to the heart of an enormous empire, as we saw in the previous chapter. Despite the evident success of the republican system, however, there were inexorable problems that plagued the Republic throughout its history, most evidently the problem of wealth and power. Roman citizens were supposed to have a stake in the Republic: all Roman citizens were bound by and protected by the laws of the state and expected by custom to put the good of the state ahead of their personal needs. Romans took pride in their Roman identity and it was the common patriotic desire to fight and expand the Republic among the citizen-soldiers of the Republic that created, at least in part, such an effective army. At the same time, the vast amount of wealth captured in the military campaigns was frequently siphoned off by elites, who found ways to seize large portions of land and loot with each campaign. As the armies of the Republic marched further from home and conquered rich lands in the eastern Mediterranean, the stakes of political battles between the most successful Roman politicians became higher and higher. The social basis of the Roman military system also transformed. Campaigns became longer, making reliance on conscripted small farmers less practical. Roman elites also concentrated more land in their families, creating pressure for reform both by the landless proletarii and by elites concerned about declining military manpower.

The key factor behind the political stability of the Republic up until the aftermath of the Punic Wars was that there had never been open fighting between elite Romans in the name of political power. Roman expansion (and especially the brutal wars against Carthage) had united the Romans. The Republican political system and the strong Roman respect for tradition had channelled elite competition into electoral campaigns rather than civil strife. A very strong component of Romanitas was the idea that political arguments were to be settled with debate and votes, not clubs and knives. Both that unity and that emphasis on peaceful conflict resolution within the Roman state itself began to crumble after the sack of Carthage.

The first step toward violent revolution in the Republic was the work of the Gracchus brothers. The older of the two was Tiberius Gracchus, a rich but reform-minded politician. Gracchus, among others, was worried that the free, farm-owning common Roman would go extinct if the current trend of rich landowners seizing farms and replacing farmers with slaves continued. Without those commoners, Rome’s armies would be drastically weakened. Thus, he managed to pass a bill through the Centuriate Assembly that would limit the amount of land a single man could own, distributing the excess to the poor. The Senate was horrified and fought bitterly to reverse the bill. Tiberius ran for a second term as tribune, something no one had ever done up to that point, and a group of senators clubbed him to death in 133 BCE.

Tiberius’s brother Gaius Gracchus took up the cause, also becoming tribune. He attacked corruption in the provinces, allying himself with the equestrian class and allowing equestrians to serve on juries that tried corruption cases. He also tried to speed up land redistribution. His most radical move was to try to extend full citizenship to all of Rome’s Italian subjects, which would have effectively transformed the Roman Republic into the Italian Republic. Here, he lost even the support of his former allies in Rome, and he killed himself in 121 BCE rather than be murdered by another gang of killers sent by senators.

The reforms of the Gracchi were temporarily successful: even though they were both killed, the Gracchi’s central effort to redistribute land accomplished its goal. A land commission created by Tiberius remained intact until 118 BCE, by which time it had redistributed huge tracts of land held illegally by the rich. Despite their vociferous opposition, the rich did not suffer much, since the lands in question were “public lands” largely left in the aftermath of the Second Punic War, and normal farmers did enjoy benefits. Likewise, despite Gaius’s death, the Republic eventually granted citizenship to all Italians in 84 BCE, after being forced to put down a revolt in Italy. In hindsight, the historical importance of the Gracchi was less in their reforms and more in the manner of their deaths – for the first time, major Roman politicians had simply been murdered (or killed themselves rather than be murdered) for their politics. It became increasingly obvious that true power was shifting away from rhetoric and toward military might.

A contemporary of the Gracchi, a general named Gaius Marius, took further steps that eroded the traditional Republican system. Marius combined political savvy with effective military leadership. Marius was both a consul (elected an unprecedented seven times) and a general, and he used his power to eliminate the property requirement for membership in the army. This allowed the poor to join the army in return for nothing more than an oath of loyalty, one they swore to their general rather than to the Republic. Marius was popular with Roman commoners because he won consistent victories against enemies in both Africa and Germany, and because he distributed land and farms to his poor soldiers. This made him a people’s hero, and it terrified the nobility in Rome because he was able to bypass the usual Roman political machine and simply pay for his wars himself. His decision to eliminate the property requirement meant that his troops were totally dependent on him for loot and land distribution after campaigns, undermining their allegiance to the Republic.

A general named Sulla followed in Marius’s footsteps by recruiting soldiers directly and using his military power to bypass the government. In the aftermath of the Italian revolt of 88 – 84 BCE, the Assembly took Sulla’s command of Roman legions fighting the Parthians away and gave it to Marius in return for Marius’s support in enfranchising the people of the Italian cities. Sulla promptly marched on Rome with his army, forcing Marius to flee. Soon, however, Sulla left Rome to command legions against the army of the anti-Roman king Mithridates in the east. Marius promptly attacked with an army of his own, seizing Rome and murdering various supporters of Sulla. Marius himself soon died (of old age), but his followers remained united in an anti-Sulla coalition under a friend of Marius, Cinna.

After defeating Mithridates, Sulla returned and a full-scale civil war shook Rome in 83 – 82 BCE. It was horrendously bloody, with some 300,000 men joining the fighting and many thousands killed. After Sulla’s ultimate victory he had thousands of Marius’s supporters executed. In 81 BCE, Sulla was named dictator; he greatly strengthened the power of the Senate at the expense of the Plebeian Assembly, had his enemies in Rome murdered and their property seized, then retired to a life of debauchery in his private estate (and soon died from a disease he contracted). The problem for the Republic was that, even though Sulla ultimately proved that he was loyal to republican institutions, other generals might not be in the future. Sulla could have simply held onto power indefinitely thanks to the personal loyalty of his troops.

Julius Caesar

Thus, there is an unresolved question about the end of the Roman Republic: when a new politician and general named Julius Caesar became increasingly powerful and ultimately began to replace the Republic with an empire, was he merely making good on the threat posed by Marius and Sulla, or was there truly something unprecedented about his actions? Julius Caesar’s rise to power is a complex story that reveals just how murky Roman politics were by the time he became an important political player in about 70 BCE. Caesar himself was both a brilliant general and a shrewd politician; he was skilled at keeping up the appearance of loyalty to Rome’s ancient institutions while exploiting opportunities to advance and enrich himself and his family. He was loyal, in fact, to almost no one, even old friends who had supported him, and he also cynically used the support of the poor for his own gain.

Two powerful politicians, Pompey and Crassus (both of whom had risen to prominence as supporters of Sulla), joined together to crush the slave revolt of Spartacus in 70 BCE and were elected consuls because of their success. Pompey was one of the greatest Roman generals, and he soon left to eliminate piracy from the Mediterranean, to conquer the Jewish kingdom of Judea, and to crush an ongoing revolt in Anatolia. He returned in 67 BCE and asked the Senate to approve land grants to his loyal soldiers for their service, a request that the Senate refused because it feared his power and influence with so many soldiers who were loyal to him instead of the Republic. Pompey reacted by forming an alliance with Crassus and with Julius Caesar, who was a member of an ancient patrician family. This group of three is known in history as the First Triumvirate.

Each member of the Triumvirate wanted something specific: Caesar hungered for glory and wealth and hoped to be appointed to lead Roman armies against the Celts in Western Europe, Crassus wanted to lead armies against Parthia (i.e. the “new” Persian Empire that had long since overthrown Seleucid rule in Persia itself), and Pompey wanted the Senate to authorize land and wealth for his troops. The three of them had so many clients and wielded so much political power that they were able to ratify all of Pompey’s demands, and both Caesar and Crassus received the military commissions they hoped for. Caesar was appointed general of the territory of Gaul (present-day France and Belgium) and he set off to fight an infamous Celtic king named Vercingetorix.

From 58 to 50 BCE, Caesar waged a brutal war against the Celts of Gaul. He was both a merciless combatant, who slaughtered whole villages and enslaved hundreds of thousands of Celts (killing or enslaving over a million people in the end), and a gifted writer who wrote his own accounts of his wars in excellent Latin prose. His forces even briefly invaded England, which a hundred years later would be conquered and incorporated into the Roman Empire. All of the lands he conquered were subjugated so thoroughly that the descendants of the Celts ended up speaking languages based on Latin, like French, rather than their native Celtic dialects.

Caesar’s victories made him famous and immensely powerful, and they ensured the loyalty of his battle-hardened troops. In Rome, senators feared his power and called on Caesar’s former ally Pompey to bring him to heel (Crassus had already died in his ill-considered campaign against the Parthians; his head was used as a prop in a Greek play staged by the Parthian king). Pompey, fearing his former ally’s power, agreed and brought his armies to Rome. The Senate then recalled Caesar after refusing to renew his governorship of Gaul and his military command, or allowing him to run for consul in absentia.

The Senate hoped to use the fact that Caesar had violated the letter of republican law while on campaign to strip him of his authority. Caesar had committed illegal acts, including waging war without authorization from the Senate, but he was protected from prosecution so long as he held an authorized military command. By refusing to renew his command or allow him to run for office as consul, he would be open to charges. His enemies in the Senate feared his tremendous influence with the people of Rome, so the conflict was as much about factional infighting among the senators as fear of Caesar imposing some kind of tyranny.

Caesar knew what awaited him in Rome – charges of sedition against the Republic – so he simply took his army with him and marched off to Rome. In 49 BCE, he dared to cross the Rubicon River in northern Italy, the legal boundary over which no Roman general was allowed to bring his troops; he reputedly announced that “the die is cast” and that he and his men were now committed to either seizing power or facing total defeat. The brilliance of Caesar’s move was that he could pose as the champion of his loyal troops as well as that of the common people of Rome, whom he promised to aid against the corrupt and arrogant senators; he never claimed to be acting for himself, but instead to protect his and his men’s legal rights and to resist the corruption of the Senate.

Pompey had been the most powerful man in Rome, both a brilliant general and a gifted politician, but he did not anticipate Caesar’s boldness. Caesar surprised him by marching straight for Rome. Pompey only had two legions, both of whom had served under Caesar in the past and, and he was thus forced to recruit new troops. As Caesar approached, Pompey fled to Greece, but Caesar followed him and defeated his forces in battle in 48 BCE. Pompey himself escaped to Egypt, where he was promptly murdered by agents of the Ptolemaic court who had read the proverbial writing on the wall and knew that Caesar was the new power to contend with in Rome. Subsequently, Caesar came to Egypt and stayed long enough to forge a political alliance, and carry on an affair, with the queen of Egypt: Cleopatra VII, last of the Ptolemaic dynasty. Caesar helped Cleopatra defeat her brother (to whom she was married, in the Egyptian tradition) in a civil war and to seize complete control over the Egyptian state. She also bore him his only son, Caesarion.

Caesar returned to Rome two years later after hunting down Pompey’s remaining loyalists. There, he had himself declared dictator for life and set about creating a new version of the Roman government that answered directly to him. He filled the Senate with his supporters and established military colonies in the lands he had conquered as rewards for his loyal troops (which doubled as guarantors of Roman power in those lands, since veterans and their families would now live there permanently). He established a new calendar, which included the month of “July” named after him, and he regularized Roman currency. Then he promptly set about making plans to launch a massive invasion of Persia.

Instead of leading another glorious military campaign, however, in March of 44 BCE Caesar was assassinated by a group of senators who resented his power and genuinely desired to save the Republic. The result was not the restoration of the Republic, however, just a new chapter in the Caesarian dictatorship. Its architect was Caesar’s heir, his grand-nephew Octavian, to whom Caesar left (much to almost everyone’s shock) almost all of his vast wealth.

Mark Antony and Octavian

Following his death, Caesar’s right-hand man, a skilled general named Mark Antony, joined with Octavian and another general named Lepidus to form the “Second Triumvirate.” In 43 BCE they seized control in Rome and then launched a successful campaign against the old republican loyalists, killing off the men who had killed Caesar and murdering the strongest senators and equestrians who had tried to restore the old institutions — most famously the great orator and politician Cicero, whose writings would later come to define Latin style but who had made an enemy of Antony. Mark Antony and Octavian soon pushed Lepidus to the side and divided up control of Roman territory – Octavian taking Europe and Mark Antony taking the eastern territories and Egypt. This was an arrangement that was not destined to last; the two men had only been allies for the sake of convenience, and both began scheming as to how they could seize total control of Rome’s vast empire.

Mark Antony moved to the Egyptian city of Alexandria, where he set up his court. He followed in Caesar’s footsteps by forging both a political alliance and a romantic relationship with Cleopatra, and the two of them were able to rule the eastern provinces of the Republic in defiance of Octavian. In 34 BCE, Mark Antony and Cleopatra declared that Cleopatra’s son by Julius Caesar, Caesarion, was the heir to Caesar (not Octavian), and that their own twins were to be rulers of Roman provinces. Rumors in the west claimed that Antony was under Cleopatra’s thumb (which is unlikely: the two of them were both savvy politicians and seem to have shared a genuine affection for one another) and was breaking with traditional Roman values, and Octavian seized on this behavior to claim that he was the true protector of Roman morality. Soon, Octavian produced a will that Mark Antony had supposedly written ceding control of Rome to Cleopatra and their children on his death; whether or not the will was authentic, it fit in perfectly with the publicity campaign on Octavian’s part to build support against his former ally in Rome.

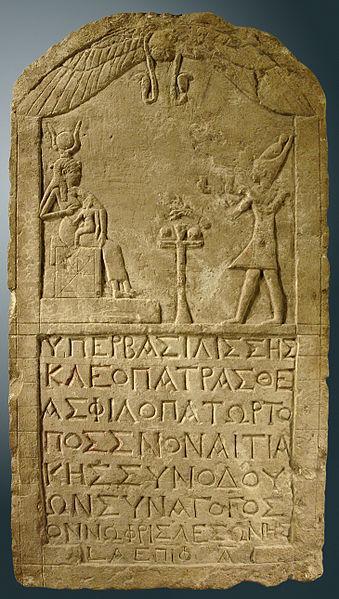

8.2 A dedication featuring Cleopatra VII making an offering to the Egyptian goddess Isis. Note the remarkable mix of Egyptian and Greek styles: the image is in keeping with traditional Egyptian carvings, and Isis is an ancient Egyptian goddess, but the dedication itself is written in Greek.

When he finally declared war in 32 BCE, Octavian claimed he was only interested in defeating Cleopatra, which led to broader Roman support because it was not immediately stated that it was yet another Roman civil war. Antony and Cleopatra’s forces had been weakened due to a disastrous campaign against the Persians a few years earlier. In 31 BCE, Octavian defeated Mark Antony’s forces. Antony and Cleopatra’s soldiers were starved out by a successful blockade engineered by Octavian and his friend and chief commander Agrippa, and the unhappy couple killed themselves the next year in exile. Octavian was 33. As his grand-uncle had before him, Octavian began the process of manipulating the institutions of the Republic to transform it into something else entirely: an empire.

The Empire under Augustus

While modern historians refer to Augustus as the first emperor of Rome, that is not the title that he himself had, nor would he have said that he was creating a new form of government. Rather, throughout his time in power, Augustus claimed to have restored the Roman Republic, and with the exception of a few elected offices, he did not have any official position. Indeed, ‘Augustus’ was a name and title that Octavian was awarded by the Senate; it had no special powers or standing associated with it, although after his death it became the title that designated the ruler of the Empire. How did Augustus manage to rule the Roman Empire for over forty years without a powerful formal title such as dictator? Some answers can be found in the Res Gestae Divi Augusti, an autobiography that Augustus himself composed in the year before he died and which he ordered to be posted on his Mausoleum in Rome, with copies also posted in all major cities throughout the Empire.

Reflecting on his forty-year rule, Augustus described himself as the first citizen, or princeps, of the Roman state, superior to others in his auctoritas. In addition, he was especially proud of the title of “Pater Patriae,” or “Father of the Fatherland,” voted to him by the Senate and reflecting his status as the patron of all citizens. It is striking to consider that other than these honorary titles and positions, Augustus did not have an official position as a ruler. Indeed, having learned from Caesar’s example, he avoided accepting any titles that might have smacked of a desire for kingship. The main formal power he maintained for himself was that of a tribune, the power to veto legislation. Instead, he burnished his prestige with new honorary titles and what powers he had were thoroughly grounded in previous Republican tradition. In addition, he proved to be a master diplomat, who shared power with the Senate in a way beneficial to himself, and by all of these actions seamlessly married the entire Republican political structure with one-man rule. Augustus’ authority was based on personal authority and legitimacy: he was the wealthiest Roman, the most famous, the most influential. He could make or break anyone’s career; the senate was filled with his allies; the legions were under his personal command or that of trusted friends and relatives. His victories in the civil war had burnished his reputation for virtus and his maintenance of the peace afterwards allowed him to cultivate a reputation for all the other Roman virtues. Ultimately, he had no need to change or abolish the republican institutions of Rome: he could easily win any election he chose and pass any law he liked through the combination of his personal wealth, popularity, and network of friends and clients.

As emperor, Augustus successfully tackled problems that had plagued Rome for at least a century. He reduced the standing army from 600,000 to 200,000 and provided land for thousands of discharged veterans in recently conquered areas such as in Gaul and Hispania. He also created new taxes specifically to fund land and cash bonuses for future veterans. To encourage native peoples in the provinces to adopt Roman culture, he granted them citizenship after twenty-five years of service in the army. Indigenous cities built in the Roman style and adopting its political system were designated municipia, which gave all elected officials Roman citizenship. Through these “Romanization” policies, Augustus advanced Roman culture across the empire.

In presenting himself as the father of the fatherland, Augustus took on the role of ordering and controlling Roman behaviour like a paterfamilias over his children. One aspect of this was his attempt to reform and improve Roman morals, returning them to the (mythical) virtue of the past. Central to this was his imposition of traditional values and behaviours on families across the Empire with new laws, introduced in 18-17 BCE. Augustus’ new laws targeted both men and women between the ages of 20 and 55, who were rewarded for being in healthy relationships, and punished if unmarried or childless. Additionally, Augustus enforced the divorce and punishment of adulterous wives. A woman’s private relationships now became a publicly regulated matter. The plan was that women would be returned to their proper places as chaste wives and mothers, and thus household order would be restored. Augustus went so far as to punish and exile his own daughter, Julia, for engaging in extramarital affairs.

Augustus also began a vast building program in the city of Rome. It jobs for poor Romans in the city and reportedly Augustus boasted that he had transformed Rome from a city of brick to a city of marble. To win over the masses, he also provided free grain (courtesy of his control of fertile Egypt) and free entertainment (gladiator combats and chariot races), making Rome famous for its bounty of “bread and circuses.” He also established a permanent police force in the city, the Praetorian Guard, which he recruited from the Roman army. He even created a publicly funded fire department.

Living in a Golden Age

While the political structure of the Roman Republic in its final century of existence was increasingly unstable, entertainment culture and literary arts flourished in Rome. Although much of Roman literary culture was based on Greek literature, the Romans adapted what they borrowed to make it distinctly their own. While adapting Greek tragedies and comedies and, in some cases, apparently translating them wholesale, Romans still injected Roman values into them, thus making them relatable to republican audiences. Similarly, while Roman philosophy and rhetoric of the Republic were heavily based on their Greek counterparts, their writers thoroughly Romanized the concepts discussed, as well as the presentation. Cicero, for instance, adapted the model of the Socratic dialogue in several of his philosophical treatises to make dialogues between prominent Romans of the Middle Republic. His De Republica, a work expressly modeled on Plato’s Republic, features Scipio Aemilianus, the victor over Carthage in the Third Punic War.

While the late Republic was a period of growth for Roman literary arts, with much of the writing done by politicians, the age of Augustus saw an even greater flourishing of Roman literature. This increase was due in large part to Augustus’ own investment in sponsoring prominent poets to write about the greatness of Rome. The three most prominent poets of the Augustan age—Virgil, Horace, and Ovid—all wrote poetry glorifying Augustan Rome. Virgil’s Aeneid, finished in 19 BCE, aimed to be the Roman national epic and indeed achieved that goal. The epic, intended to be the Roman version of Homer’s Iliad and Odyssey combined, describes the travels of the Trojan prince Aeneas who, by will of the gods, became the founder of Rome. Clearly connecting the Roman to the Greek heroic tradition, the epic also includes a myth explaining the origins of the Punic Wars: during his travels, before he arrived in Italy, Aeneas was ship-wrecked and landed in Carthage. Dido, the queen of Carthage, fell in love with him and wanted him to stay with her, but the gods ordered Aeneas to sail on to Italy. After Aeneas abandoned her, Dido committed suicide and cursed the future Romans to be at war with her people.

The works of Horace and Ovid were more humorous at times, but they still included significant elements from early Roman myths. They showcased the pax deorum that caused Rome to flourish in the past and, again now, in the age of Augustus. Ovid appears to have pushed the envelope beyond acceptable limits, whether in his poetry or in his personal conduct. Therefore, Augustus exiled him in 8 CE to the city of Tomis on the Black Sea, where Ovid spent the remainder of his life writing mournful poetry and begging unsuccessfully to be recalled to Rome.

In addition to sponsoring literature, the age of Augustus sponsored architecture as well. In his Res Gestae, Augustus includes a very long list of temples that he had restored or built. These building projects stood as symbols of renewal and prosperity ordained by the gods themselves. One famous example is the Ara Pacis, or Altar of Peace, in Rome. The altar features mythological scenes and processions of gods; it also integrates scenes of the imperial family, including Augustus himself making a sacrifice to the gods while flanked by his grandsons Gaius and Lucius.

The message of these building projects, as well as the other arts that Augustus sponsored, is simple: Augustus wanted to show that his rule was a new Golden Age of Roman history, a time when peace was restored and Rome flourished, truly blessed by the gods.

Economy

The Roman economy was a massive and intricate system. Goods produced in and exported from the region found their way around the Mediterranean, while luxury goods brought from distant locales were cherished in the empire. The sea and land routes that connected urban hubs were crucial to this exchange. The collection of taxes funded public works and government programs for the people, keeping the economic system functioning. The Roman army was an extension of the economic system; financing the military was an expensive endeavour, consuming about 70% of the state budget, but the security it provided made the continued existence of the state and the state economy possible.

Augustus’ long reign initiated the Pax Romana, a term referring to the relative peace that largely prevailed within the borders of the Roman state. This peace, while interrupted both by low level banditry and occasional invasions and civil strife, prevailed for a remarkable proportion of the next four centuries. This peace formed the basis of an economic expansion that lead to large-scale population growth in the Roman state. The archaeological evidence for this economic expansion is broad, ranging from the frequency of shipwrecks to the traces of lead pollution in Greenland ice from the time period. The foundation of this expansion was agriculture, the basis of every premodern economy. Intensive grain production in the ‘breadbasket’ provinces of Africa and Egypt was shipped throughout the Mediterranean. This allowed other areas to specialize in their most efficient cash crops, including olives in Greece and Italy and wine in the south of France.

Trade

Sea routes facilitated the movement of goods around the empire. Though the Romans built up a strong network of roads, shipping by sea was considerably less expensive. Thus, access to a seaport was crucial to trade. In Italy, there were several fine seaports, with the city of Rome’s port at Ostia being a notable example. Italy itself was the producer of goods that made their way around the Mediterranean. Most manufacturing occurred on a small scale, with shops and workshops often located next to homes. Higher-value goods did find their way to distant regions, and Italy dominated the western trade routes.

The suppression of pirates and bandits, the building of road networks, and the unified laws and government of the Empire together led to a flourishing of agriculture, manufacture and trade. Regions and cities were able to specialize and invest in large-scale production, making use of Rome’s internal trade connections to find markets for their goods. That some large estates could produce a massive surplus for trade is evidenced at archaeological sites across the empire: wine producers in southern France with cellars capable of storing 100,000 litres, an olive oil factory in Libya with 17 presses capable of producing 100,000 litres a year, or gold mines in Spain producing 9,000 kilos of gold a year. Although towns were generally centres of consumption rather than production, there were exceptions where workshops could produce impressive quantities of goods. These ‘factories’ might have been limited to a maximum workforce of 30 but they were often collected together in extensive industrial zones in the larger cities and harbours, and in the case of ceramics, also in rural areas close to essential raw materials (clay and wood for the kilns).

Italy was known for its ceramic, marble, and metal industries. Building supplies such as tiles, marble, and bricks were also produced in Italy. Bronze goods such as cooking equipment and ceramic tableware known as red pottery were especially popular items. These industries likewise relied on imports, including copper from mines in Spain and tin from Britain for making bronze.Red Samian pottery made its way to places around the Mediterranean and beyond, including Britain and India. Iron goods produced in Italy were exported to Germany and to the Danube region, while bronze goods, most notably from Capua, circulated in the northern reaches of the empire before workshops also developed there. Other Roman industries balanced their production with imported goods from foreign markets. Textiles such as wool and cloth were produced in Italy, while luxury items like linen came from Egypt.For a time, central Italy manufactures and exported glass products northward, until manufacturing in Gaul (present-day France) and Germany took over the majority of its production in the second century CE.

Agricultural goods were an important aspect of the Roman economy and trade networks. Grain-producing Egypt functioned as the empire’s breadbasket, and Italian farmers were therefore able to focus on other, higher-priced agricultural products including wine and olive oil. Wine was exported to markets all over the Mediterranean, including Greece and Gaul. Both wine and olive oil, as well as other goods, were usually shipped in amphorae. These large storage vases had two handles and a pointed end, which made them ideal for storing during shipment. They may have been tied together or placed on a rack when shipped by sea.

The government’s official distribution of grain to the populace was called the annona and was especially important to Romans. It had begun in the second century BCE but took on new importance by the reign of Augustus. The emperor appointed the praefectus annonae, the prefect who oversaw the distribution process, governed the ports to which grain was shipped, and addressed any fraud in the market. The prefect and his staff also secured the grain supply from Egypt and other regions by signing contracts with various suppliers.

The Roman government was also generally concerned with controlling overseas trade. An elite class of shipowners known as the navicularii were compelled by the government to join groups known as collegia (corporations) so they could be easily supervised. For signing contracts to supply grain, these shipowners received benefits including exemption from other public service. By the third and fourth centuries CE, control of the navicularii had intensified, and signing contracts to supply the annona was compulsory.

The annona kept the populace fed but was also a political tool; the emperor hoped his generosity would endear him to the people. The distribution of grain was thus heavily tied to the personality of the emperor. For instance, like many emperors, Hadrian, who ruled from 138 to 161 CE, associated himself with the annona to create a positive image before the public.

Eurasian Connections

In addition to the dense trade connections within Rome’s borders, Rome was also connected via trade to much of the rest of Afro-Eurasia. The use of different trading routes ensured a constant stream of exotic goods in the Roman Empire. Perhaps more importantly, they integrated Rome into a growing network of connections across the continents that shared languages, culture and ideas. The many merchants, porters, craftsmen, and sailors that engaged in this trade network created an international system that would endure through many transformations up until the present day. Goods from the Far East and Africa arrived via this enormous network into Roman territory through two corridors – the Red Sea and the Persian Gulf.

The Red Sea corridor required a trip by ship of 4,500 km (2800 mi) from India to the Red Sea port cities, followed by a caravan route of 380 km (236 mi) across the Egyptian Desert, and then another 760 km (472 mi) by ship on the Nile to the Mediterranean, for a total distance of 5,640 km (3500 mi). The Persian Gulf corridor required a trip by ship of 2,350 km (1460 mi) from India to the confluence of the Tigris and Euphrates Rivers and then by caravan across the Syrian desert for 1,400 km (870 mi), for a total of 3,750 km (2330 mi). To get to India, Chinese silk had traveled another 5,000 km (3100 mi) across the rugged, mountainous terrain of Central China to the Indian Ports.

The price and scarcity of luxuries from distant lands made them irresistibly attractive to elite Romans. Stylish Romans adorned themselves with cosmetics and perfumes made with cinnamon from Sri Lanka, myrrh from Somalia, and frankincense from Yemen, and they wore clothing of translucent silk from China. Fragrant incenses had long had a place in Roman religious ritual. The streets were filled with fragrant smoke from frankincense and myrrh wafting from burners at the base of statues of the Roman emperor, and the Roman cuisine was spiced with pepper and ginger from India. Silk became so popular that the Roman Senate periodically issued proclamations (mostly in vain) to prohibit the wearing of silk on both economic and moral grounds. Bolts of thick Chinese silk cloth were picked apart and rewoven at manufactories into thin and translucent garments that moralists complained left nothing to the imagination and were little better than nudity.

Although Rome had no direct contact with China, both states were aware of each other via their mutual connections with Persia and India. China was first unified under the Qing dynasty while Rome was in its Republican period fighting wars against Carthage, and the long foundational rule of the Han dynasty overlapped the end of the Roman republic and the first several centuries of Empire. They were the largest and most powerful of the dozens of states that were spread across Eurasia that became connected and to some degree integrated by the growth of the transcontinental trade in this time period. Trading cities such as Palmyra and Samarkand served as connective hubs for merchants and travellers, growing wealthy on the profits of the caravans that passed through them.

Taxes

Collecting taxes was a chief concern of the Roman government because tax revenues were a necessity for conducting business and funding public programs. Taxes fell into several categories, including those calculated with census lists in the provinces, import and customs taxes, and taxes levied on particular groups and communities.

Upper-class investment in the provinces drove the economy and facilitated the collection of taxes. An important role in this system was played by the publicani, who operated as tax collectors in the provinces. These contractors first bid for the right to collect taxes by making a direct payment to the Roman government, which functioned as a de facto loan. To recover their investment, the publicani then collected taxes from provincial residents, keeping any money in excess of their original bid in addition to a percentage paid by the Roman government.

The publicani ran an effective system of tax collection, but it was imprecise and they were often accused of fraud. During the reign of Augustus, the publicani system was essentially abolished. In the revised system, provincials had to pay roughly 1 percent tax on their wealth, which included their assets in the form of land, as well as a flat poll tax. This new tax structure was assessed through census lists and administered by procurators, imperial officials who made collections and oversaw the payment of public officials in the province.

Other taxes included those on inheritances and legacies. To raise funds for paying veteran soldiers, in 6 CE, Augustus codified a new 5 percent tax on money inherited through a will. The rule excluded inheritances from close relatives, however, and was directly aimed at traditional patron-client relationships. With this tax, Augustus disrupted elite patron-client networks that had relied on the formation of social bonds outside the immediate family. As a result, the elite were compelled to coalesce around the figure of the emperor as the ultimate patron.

Despite these attempts at collecting taxes, by the third century CE the empire had entered a period of financial crisis. Constant wars meant a never-ending need to sustain large armies. As less new land was acquired, troop payments came more often from the central treasury than from newly conquered territory. The financial pressure proved critical. The emperor Diocletian implemented a series of measures to address the problems. For example, in 301, to combat inflation, Diocletian issued the Edict on Maximum Prices, which set a price ceiling for certain goods and services. Diocletian’s reforms also increased the money collected by the government with two new taxes, on agricultural land and on individuals. The inclusion of property in Italy in the land tax for the first time, as well as Diocletian’s standardization of a five-year census, dramatically increased revenue for the empire. Replacing some of Rome’s revenue shortfall through these taxes helped stabilize the economy in the short term.

Conquest

Periods of conquest contributed to the Roman economy in a number of ways. The Romans sought to control natural resources and attain wealth from the regions they conquered. By harnessing the revenues of conquest, they could support their goals of keeping the populace fed and the troops paid.

In early Rome, the army was a militia force mustered during times of conflict. By the time of the empire, however, it had become a standing professional army. The Roman legion was the building block of that army, an independent and self-contained military unit that had the necessary troops, officers and support staff to fight during war and maintain itself in peace. Though its organization changed over time, a legion consisted of about five thousand soldiers and was commanded by a legate. A legion also included associated craftspeople and other essential noncombatants. Following the reforms of Augustus, twenty-eight legions were stationed throughout the provinces of the empire and on the frontier. They were numbered but also had nicknames based on their place of origin or service. Since legions could move around the empire, the First German legion might be found in Spain, for example. Soldiers served a sixteen-year term, though this was later raised to twenty, and they were paid a set amount at the end of their service. Soldiers and military staff received a large portion of the wealth secured during wartime, and some were also occasionally promised land taken in the various conflicts that Rome engaged in.

Many military engagements were clearly intended to secure resources and capital. For instance, the empire’s grain supply was vastly expanded by its conquest of Egypt in the first century BCE, as well as of Sicily and Sardinia early in Rome’s history. In addition, people captured in conquest were often sold in the Roman slave markets. Since the work of enslaved and freed people was the backbone of Roman industry, enslaved people too contributed to the functioning of the economy.

But there were trade-offs in this arrangement. The increasing size of the Roman military and the empire’s expanding frontier made conflict more costly. While earlier in its history, Rome’s soldiers might expect to campaign only part of the year, by the imperial period, conflict had become a regular situation on the frontier. Campaigns could last for months on end, and in some situations wars may have seemed endless. The distance from the city of Rome also contributed to the cost of running the military; far-flung military campaigns were expensive. The machinery of running and paying the army necessitated further conquest, a situation that ultimately strained the Roman military.

In addition, there were clearly societal disadvantages to continuous conflict. Though Romans took pride in their military superiority, the loss of life and property must have been a burden for many. Conflict abroad disrupted regional markets that Italy depended on. For example, an interruption in the grain supply in 190 CE resulted in famine and riots in the city of Rome. Elites were largely able to benefit from the economic arrangement of conquest, but those in the lower classes no doubt shouldered the burden of its negative consequences.

Early Christianity

The birth of Jesus occurred during the reign of Augustus and his death probably during the principate of Augustus’ successor, Tiberius. The historical details of Jesus’s life are difficult to reconstruct with certainty: there are few contemporary references to him, and the copious material that was written after his death (particularly the four Gospels) give somewhat different versions of key details that would be needed to assign exact dates to the various events in his life. The broad details, however, are fairly clear: Jesus was a Jewish man born in Nazareth who was later executed by the Roman governer Pontius Pilate for alleged political crimes. His execution was connected to his preaching; he had attracted followers to his vision of brotherhood, poverty and the rejection of various tenets of the Pharisaic Judaism that was politically dominant in Judea. Those followers grew rapidly in number after his death, particularly due to the efforts of Paul of Tarsus, soon developing a substantially new religion, Christianity, based on the teachings of Jesus as presented by authors who had either known him personally or met those who had.

Early Christianity is, in some ways, an ancient historian’s dream: for few other topics in Roman history do we have so many primary sources from both the perspective of insiders and outsiders, beginning with the earliest days of the movement. The New Testament, in particular, is a collection of primary sources by early Christians about their movement, with some of the letters composed merely twenty-five years after Jesus’ crucifixion. It is a remarkably open document, collecting theological beliefs and stories about Jesus on which the faith was built. At the same time, however, the New Testament does not “white-wash” the early churches; rather, it documents their failings and short-comings with remarkable frankness, allowing the historian to consider the challenges that the early Christians faced from not only the outside but also within the movement.

The story of the origins of the faith is explained more plainly in the four Gospels, placed at the beginning of the New Testament. While different emphases are present in each of the four Gospels, the basic story is as follows: God himself came to earth as a human baby, lived a life among the Jews, performed a number of miracles that hinted at his true identity, but ultimately was crucified, died, and rose again on the third day. His resurrection proved to contemporary witnesses that his teachings were true and inspired many of those who originally rejected him to follow him. While the movement originated as a movement within Judaism, it ultimately floundered in Judea but quickly spread throughout the Greek-speaking world—due to the work of such early missionaries as Paul.

It would be no exaggeration to call the early Christian movement revolutionary. In a variety of respects, it went completely against every foundational aspect of Roman (and, really, Greek) society. First, the Christian view of God was very different from the pagan conceptions of gods throughout the ancient Mediterranean. Roman religion was defined by public rituals and was directed at achieving beneficial results in the here and now by attracting divine favour (or avoiding divine enmity). By contrast, Jesus’ preaching focused on the notion of divine reward or punishment after death. While in traditional Roman paganism the gods had petty concerns and could treat humans unfairly, if they so wished, Christianity by contrast presented the message that God himself became man and dwelt with men as an equal. This concept of God incarnate had revolutionary implications for social relations in a Christian worldview. For early Christians, their God’s willingness to take on humanity and then sacrifice himself for the sins of the world served as the greatest equalizer: since God had suffered for all of them, they were all equally important to him, and their social positions in the Roman world had no significance in God’s eyes. Finally, early Christianity was an apocalyptic religion. Many early Christians believed that Jesus was coming back soon, and they eagerly awaited his arrival, which would erase all inequality and social distinctions while punishing the wicked and reviving the dead martyrs the faith.

The egalitarian early Christian community stood in stark contrast to the social hierarchy of the Augustan age. While social mobility was possible—for instance, slaves could be freed, and within a generation, their descendants could be Senators—extreme mobility was the exception rather than the rule. Furthermore, gender roles in Roman society were extremely rigid, as all women were subject to male authority. Indeed, as we have seen, the paterfamilias had the power of life or death over all living under his roof, including in some cases adult sons, who had their own families. Christianity challenged all of these traditional relationships, nullifying any social differences, and treating the slave and the free the same way. Furthermore, Christianity provided a greater degree of freedom than women had previously known in the ancient world, with only the Stoics coming anywhere close in their view on gender roles. Christianity allowed women to serve in the church and remain unmarried, if they so chose, and numerous women are known to have had prominent roles in the early church, including leading congregations, . Women could become heroes of the faith by virtue of their lives or deaths, as in the case of the early martyrs. Indeed, the Passion of the Saints Perpetua and Felicity, which documents the two women’s martyrdom in Carthage in 203 CE, shows all of these reversals of Roman tradition in practice.

The Passion of the Saints Perpetua and Felicity was compiled by an editor shortly after the fact and includes Perpetua’s own prison diary, as she awaited execution. The inclusion of a woman’s writings already makes the text unusual, as almost all surviving texts from the Roman world are by men. In addition, Perpetua was a noblewoman, yet she was imprisoned and martyred together with her slave, Felicity. The two women, as the text shows, saw each other as equals, despite their obvious social distinction. Furthermore, Perpetua challenged her father’s authority as paterfamilias by refusing to obey his command to renounce her faith and thus secure freedom. Such outright disobedience would have been shocking to Roman audiences. Finally, both Perpetua and Felicity placed their role as mothers beneath their Christian identity, as both gave up their babies in order to be able to be martyred. Their story, as those of other martyrs, was truly shocking in their rebellion against Roman values, but their extraordinary faith in the face of death proved to be contagious. As recent research shows, conversion in the Roman Empire sped up over the course of the second and third centuries CE, despite periodic persecutions by such emperors as Septimius Severus, who issued an edict in 203 CE forbidding any conversions to Judaism and Christianity. That edict led to the execution of Perpetua and Felicity.

Most of the early Christians lived less eventful (and less painful) lives than Perpetua and Felicity, but the reversals to tradition inherent in Christianity appear clearly in their lives as well. First, the evidence of the New Testament, portions of which were written as early as the 60s CE, shows that the earliest Christians were from all walks of life; Paul, for instance, was a tent-maker. Some other professions of Christians and new converts that are mentioned in the New Testament include prison guards, Roman military officials of varying ranks, and merchants. Some, like Paul, were Roman citizens, with all the perks inherent in that position, including the right of appeal to the Emperor and the right to be tried in Rome. Others were non-citizen free males of varying provinces, women, and slaves. Stories preserved in Acts and in the epistles of Paul that are part of the New Testament reveal ways—the good, the bad, and the ugly—in which these very different people tried to come together and treat each other as brothers and sisters in Christ. Some of the struggles that these early churches faced included sexual scandal (the Corinthian church witnessed the affair of a stepmother with her stepson), unnecessary quarrelling and litigation between members, and the challenge of figuring out the appropriate relationship between the requirements of Judaism and Christianity (to circumcise or not to circumcise? That was the question. And then there were the strict Jewish dietary laws). It is important to note that early Christianity appears to have been predominantly an urban religion and spread most quickly throughout urban centers. Thus Paul’s letters address the churches in different cities throughout the Greek-speaking world and show the existence of a network of relationships between the early churches, despite the physical distance between them. Through that network, the churches were able to carry out group projects, such as fundraising for areas in distress, and could also assist Christian missionaries in their work. By the early second century CE, urban churches were led by bishops, who functioned as overseers for spiritual and practical matters of the church in their region.

This chapter is partly adapted from

Western Civilization: A Concise History by Christopher Brooks and is used under a CC BY-NC-SA 4.0 license.

World History: Cultures, States and Societies to 1500 by Berger et. al. and is used under a CC BY-SA 4.0 license.

World History, Volume 1 by openstax.org, used under a CC-BY 4.0 license.

Trade in the Roman World by Mark Cartwright at the World History Encyclopedia and is used under a CC BY-NC-SA 4.0 license.

The Eastern Trade Network of Ancient Rome by James Hancock at the World History Encyclopedia and is used under a CC BY-NC-SA 4.0 license.

Women in Ancient Rome by Wikipedia, used under a CC BY-SA 4.0 license.

Media Licenses

8.1 First Triumvirate by Andreas Wahra, in the public domain

8.2 Cleopatra VII by Jastrow, in the public domain

8.3 Statue of Augustus from the Villa of Livia at Prima Porta by Till Niermann, Public Domain

8.4 The Ara Pacis by Manfred Heyde under CC BY-SA 3.0

8.5 Trade Routes of the Roman Empire by Rice University, OpenStax, under CC BY 4.0

8.6 Roman Amphora by Silar – Own work, under CC BY-SA 4.0

8.7 Vespasian Dupondus by Guy de la Bedoyere, in the public domain

8.8 Roman Banquet Fresco from the Museo Archeologico Nazionale di Napoli, in the public domain

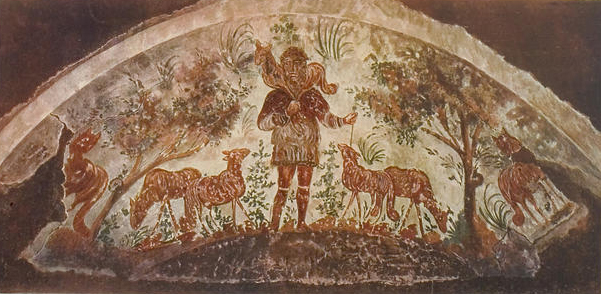

8.9 Roman depiction of Christ as the Good Shepherd by Wilpert, in the public domain

Media Attributions

- sLedziennicasanrp_KJJ

- Wilpert_117b © Wilpert

Feedback/Errata