7 The Roman Republic

Origins

Romulus

Rome was originally a town built amidst seven hills surrounded by swamps in central Italy. The Romans were just one group of “Latins,” central Italians who spoke closely-related dialects of the Latin language. Rome itself had a few key geographical advantages. Its hills were easily defensible, making it difficult for invaders to carry out a successful attack. It was at the intersection of trade routes, thanks in part to its proximity to a natural ford (a shallow part of a river that can be crossed on foot) in the Tiber River, leading to a prosperous commercial and mercantile sector that provided the wealth for early expansion. It also lay on the route between the Greek colonies of southern Italy and various Italian cultures in the central and northern part of the peninsula.

The legend that the Romans themselves invented about their own origins had to do with two brothers: Romulus and Remus. In the legend of Romulus and Remus, two boys were born to a Latin king, but then kidnapped and thrown into the Tiber River by the king’s jealous brother. They were discovered by a female wolf and suckled by her, eventually growing up and exacting their revenge on their treacherous uncle. They then fought each other, with Romulus killing Remus and founding the city of Rome. According to the story, the city of Rome was founded on April 21, 753 BCE. This legend is just that: a legend. Its importance is that it speaks to how the Romans wanted to see themselves, as the descendants of a great man who seized his birthright through force and power, accepting no equals. In a sense, the Romans were proud to believe that their ancient heritage involved being literally raised by wolves.

The Romans were a warrior people from very early on, feuding and fighting with their neighbors and with raiders from the north. They were allied with and, for a time, ruled by a neighboring people called the Etruscans who lived to the northwest of Rome. The Etruscans were active trading partners with the Greek poleis of the south, and Rome became a key link along the Etruscan – Greek trade route. The Etruscans ruled a loose empire of allied city-states that carried on a brisk trade with the Greeks, trading Italian iron for various luxury goods. This mixing of cultures, Etruscan, Greek, and Latin, included shared mythologies and stories. The Greek gods and myths were shared by the Romans, with only the names of the gods being changed (e.g. Zeus became Jupiter, Aphrodite became Venus, Hades became Pluto, etc.). In this way, the Romans became part of the larger Mediterranean world of which the Greeks were such a significant part.

According to Roman legends, the Etruscans ruled the Romans from some time in the eighth century BCE until 509 BCE. During that time, the Etruscans organized them to fight along Greek lines as a phalanx. From the phalanx, the Romans would eventually create new forms of military organization and tactics that would overwhelm the Greeks themselves (albeit hundreds of years later). There is no actual evidence that the Etruscans ruled Rome, but as with the legend of Romulus and Remus, the story of early Etruscan rule inspired the Romans to think of themselves in certain ways – most obviously in utterly rejecting foreign rule of any kind, and even of foreign cultural influence. Romans were always fiercely proud (to the point of belligerence) of their heritage and identity.

By 600 BCE the Romans had drained the swamp in the middle of their territory and built the first of their large public buildings. As noted, they were a monarchy at the time, ruled by (possibly) Etruscan kings, but with powerful Romans serving as advisers in an elected senate. Native-born men rich enough to afford weapons were allowed to vote, while native-born men who were poor were considered full Romans but had no vote. In 509 BCE (according to their own legends), the Romans overthrew the last Etruscan king and established a full Republican form of government, with elected officials making all of the important political decisions. Roman antipathy to kings was so great that no Roman leader would ever call himself Rex – king – even after the Republic was eventually overthrown centuries later.

The Roman Republic had a fairly complex system of government and representation, but it was one that would last about 500 years and preside over the vast expansion of Roman power. Their government had three main parts, each of which was very powerful in its own way: the popular assemblies, the senate, and the magistrates, headed by the consuls.

The various Roman citizen assemblies had most of the formal power in the state. They elected most magistrates, including the consuls, and could also pass laws. Successful Roman politicians needed to be able to win elections to public office and to persuade the citizens to vote for the laws they favored. This gave Roman voters substantial influence over the state, as even the most wealthy and aristocratic Roman depended on the popular will for his personal advancement.

The pinnacle of this advancement was the position of consul, which was the most prestigious step on the Roman ‘ladder of honours’, the cursus honorum. Ambitious Romans could take their first official step onto the ladder by running to be a Quaestor, who would help manage Roman finances or assist a higher ranking magistrate. A succesful politician would subsequently become an Aedile and then a Preator, eventually securing eternal glory for his family and himself by being elected Consul for a year.

The Roman Consuls were two in number and held office for one year. Their main role was leading Roman armies in the field, but they also headed the Roman justice system and informally were often the main proposers of new legislation. The powers of the consuls were equal, and either one could negate the actions of the other. For many consuls, their year in office was defined by the military campaign that they led, its outcome defining their legacy in the public mind. The chief power of the consul was imperium, a kind of embodied vision of supreme state violence. Outside the city of Rome in their military office, they could pronounce a death penalty at their discretion, and often wielded the power of life or death over entire cities. At home, in their role as head of the justice system, it was by their authority that the law might strip citizen of their possession, banish them, or put them to death. The consuls imperium was symbolized by their accompaniment of twelve lictors, men bearing a fasces, an axe symbolically bound up in a bundle of sticks, representing the violence constrained by rightful authority.

When Rome faced a major crisis, the Centuriate Assembly could vote to appoint a dictator, a single man vested with the full power of imperium, not constrained by the power of a co-equal consul. Symbolically, all twenty-four of the lictors would accompany the dictator, who was supposed to use his almost-unlimited power to save Rome from whatever threatened it, then step down and return things to normal. While the office of dictator could have easily led to an attempted takeover, for hundreds of years very few dictators abused their powers and instead respected the temporary nature of Roman dictatorship itself.

Compared to the popular assemblies, the Senate had no formal power. While the Senate was an advisory body in theory, it wielded very real informal power. Made up of the wealthiest, most successful Romans with the most auctoritas and served by the most clients, the Senate’s advice was almost always followed by the political class. The Senate was the permanent political guiding force of the Republic, ensuring that even though there would be new glory-seeking consuls every year, the Roman state could make decisions based on the careful deliberation of its most experienced politicians and generals. The Senate in practice made decisions of war and peace, with the consuls of the year being ‘advised’ by the senate whether to raise an army and where to take it.

Class Struggle

Rome struggled with a situation analogous to that of Athens, in which the rich not only had a virtual monopoly on political power, but in many cases had the legal right to either enslave or at least extract labor from debtors. In Rome’s case, an ongoing class struggle called the Conflict of Orders took place from about 500 BCE to 360 BCE (140 years!), in which the plebeians struggled to get more political representation. In 494 BCE, the plebeians threatened to simply leave Rome, rendering it almost defenseless, and the Senate responded by allowing the creation of two officials called Tribunes, men drawn from the plebeians who had the legal power to veto certain decisions made by the Senate and consuls. Later, the government created a Plebeian Council to represent the needs of the plebeians, approved the right to marry between patricians and plebeians, banned debt slavery, and finally, came to the agreement that of the two consuls elected each year, one had to be a plebeian. By 287 BCE, the Plebeian Assembly could pass legislation with the weight of law as well.

Class struggle was always a factor in Roman politics. Even after the plebeians gained legal concessions, the rich always held the upper hand because wealthy plebeians would regularly join with patricians to out-vote poorer plebeians. Likewise, in the Centuriate Assembly, the richer classes had the legal right to out-vote the poorer classes – the equestrians and patricians often worked together against the demands of the poorer classes. Practically speaking, by the early third century BCE the plebeians had won meaningful legal rights, namely the right to representation and lawmaking, but those victories were often overshadowed by the fact that wealthy plebeians increasingly joined with the existing patricians to create something new: the Roman aristocracy. Most state offices did not pay salaries, so only those with substantial incomes from land (or from loot won in campaigns) could afford to serve as full-time representatives, officials, or judges – that, too, fed into the political power of the aristocracy over common citizens.

In the midst of this ongoing struggle, the Romans came up with the basis of Roman law, the system of law that, through various iterations, would become the basis for most systems of law still in use in Europe today (Britain being a notable exception). Private law governed disputes between individuals (e.g. property suits, disputes between business partners), while public law governed disputes between individuals and the government (e.g. violent crimes that were seen as a threat to the social order as a whole). In addition, the Romans established the Law of Nations to govern the territories it started to conquer in Italy; it was an early form of international law based on what were believed to be universal standards of justice.

The plebeians had been concerned that legal decisions would always favor the patricians, who had a monopoly on legal proceedings, so they insisted that the laws be written down and made publicly available. Thus, in 451 BCE, members of the Roman government wrote the Twelve Tables, lists of the laws available for everyone to see, which were then posted in the Roman Forum in the center of Rome. Just as it was done in Athens a hundred years earlier, having the laws publicly available reduced the chances of corruption. In fact, according to a Roman legend, the ten men who were charged with recording the laws were sent to Athens to study the laws of Solon of Athens; this was a deliberate use or “copy” of his idea.

Roman Expansion

Roman soldiers under the Republic were citizen-soldiers. Any time a legion was raised, eligible Roman men were summoned to the campus Martius where some would be conscripted for the campaign. They provided their own equipment, and although they were provided with food by the state while on campaign, they were not paid for their time. They might nevertheless hope to win a share of any booty captured on campaign — which could vary from almost nothing to substantial riches, if a rich city was plundered by the army. During the height of the republic, Rome was at war with some enemy or other nearly every year, and the average male citizen would almost certainly serve multiple times on campaign. The ‘amateur’ Roman military was a very experienced and effective institution, which starting in the 4th century BCE began to systematically and consistently win wars and expand Roman power.

Roman expansion began with its leadership of a confederation of allied cities, the Latin League. Rome led this coalition against nearby hill tribes that had periodically raided the area, then against the Etruscans that had once ruled Rome itself. Just as the Romans started to consider further territorial expansion, a fierce raiding band of Celts swooped in and sacked Rome in 389 BCE, a setback that took several decades to recover from. In the aftermath, the Romans swore to never let the city fall victim to an attack again.

A key moment in the early period of Roman expansion was in 338 BCE when Rome defeated its erstwhile allies in the Latin League. Rome did not punish the cities after it defeated them, however. Instead, it offered them citizenship in its republic (albeit without voting rights) in return for pledges of loyalty and troops during wartime, a very important precedent because it meant that with every victory, Rome could potentially expand its military might. Soon, the elites of the Latin cities realized the benefits of playing along with the Romans. They were dealt into the wealth distributed after military victories and could play an active role in politics so long as they remained loyal, whereas resisters were eventually ground down and defeated with only their pride to show for it.

While Rome would rarely extend actual citizenship to whole communities in the future, the assimilation of the Latins into the Roman state did set an important precedent: conquered peoples could be won over to Roman rule and contribute to Roman power, a key factor in Rome’s ongoing expansion from that point forward. These Latin ‘allies’ provided about half the troops for Rome’s massive military machine, and they seem to have mostly considered Rome’s leadership better than the alternatives, mostly staying loyal to Rome even during its darkest days when Hannibal’s armies were rampaging through Italy trying to break up Rome’s power. This alliance system provided much of the huge manpower reserves that were perhaps the most formidable part of Rome’s military machine.

Rome rapidly expanded to encompass all of Italy except the southernmost regions. Those regions, populated largely by Greeks who had founded colonies there centuries before, invited a Greek warrior-king named Pyrrhus to aid them against the Romans around 280 BCE (Pyrrhus was a Hellenistic king who had already wrested control of a good-sized swath of Greece from the Antigonid dynasty back in Greece). Pyrrhus won two major battles against the Romans, but in the process he lost two-thirds of his troops. After his victories, he made a comment that “one more such victory will undo me” – this led to the phrase “pyrrhic victory,” which means a temporary victory that ultimately spells defeat, or winning the battle but losing the war. He took his remaining troops and returned to Greece. After he fled, the south was unable to mount much of a resistance, and all of Italy was under Roman control by 263 BCE.

Roman Militarism

It is important to emphasize the extreme militarism and terrible brutality of Rome during the republican period, very much including this early phase in which it began to acquire its empire. Wars were annual: with very few exceptions over the centuries the Roman legions would march forth to conquer new territory every single year. The Romans swiftly acquired a reputation for absolute ruthlessness and even wanton cruelty, raping and/or slaughtering the civilian inhabitants of conquered cities, enslaving thousands, and in some cases utterly wiping out whole populations (the neighboring city of Veii was obliterated in roughly 393 BCE, for example, right at the start of the conquest period). The Greek historian Polybius calmly noted at the time in his sweeping history of the republic that insofar as there was a deliberate intention behind all of this cruelty, it was easy to identify: causing terror.

Roman society placed tremendous cultural importance placed on winning military glory. Nothing was more important to a male Roman citizen than his reputation as a soldier. Likewise, Roman aristocrats all acquired much of their political power through military glory until late in the republic, and even then military glory was all but required for a man to achieve any kind of political prominence. The greatest honor a Roman could win was a triumph, a military parade displaying the spoils of war to the cheers of the people of Rome; many people held important positions in Rome, but only the greatest generals were ever rewarded with a triumph.

The overall picture of Roman culture is of a society that was in its own way as obsessed with war as was Sparta during the height of its barracks society — and in many ways, much more politically aggressive. Unlike Sparta, however, Rome was able to mobilize gigantic armies via its well-organised militia levy and its strong network of subservient allies. One prominent contemporary historian of Rome, W.V. Harris, wisely warns against the temptation of “power worship” when studying Roman history. Rome accomplished remarkable things, but it did so through appalling cruelty and astonishing levels of violence.

Rome was certainly not unique in its cruelty: neither Carthage nor the Hellenistic monarchs shrank from destroying cities or ravaging civilian populations. The Senate could also be merciful, and the Roman conquest of the Mediterranean proceeded as much because they made good allies as because they were terrifying foes. But a distinct aspect of the Republican system was that it possessed an innate and insatiable hunger for war because that was the best way for its leaders to advance their own careers. The Senate was able to harness this ambition to some degree, but eventually the Republic would be torn apart by the rivalry of its most powerful and successful generals. First, however, that rivalry would drive Roman conquests from the Atlantic ocean to the Persian gulf.

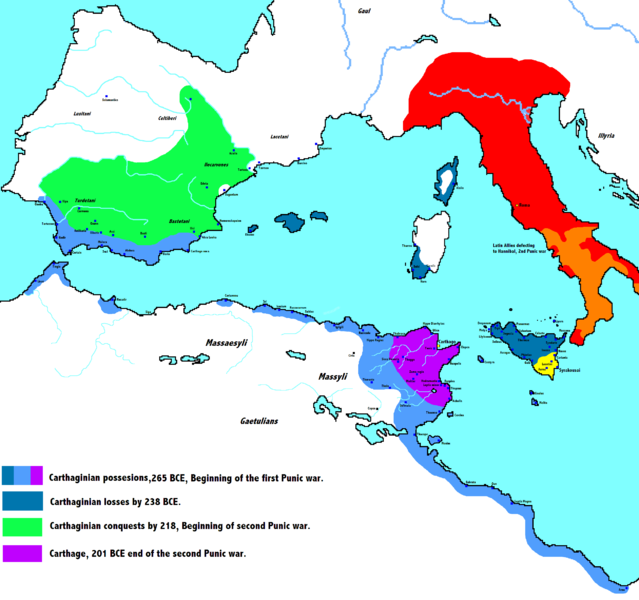

The Punic Wars

Rome’s great rival in this early period of expansion was the North-African city of Carthage, founded centuries earlier by Phoenician colonists. Carthage was one of the richest and most powerful trading empires of the Hellenistic Age, a peer of the Alexandrian empires to the east, trading with them and occasionally skirmishing with the Ptolemaic armies of Egypt and with the Greek cities of Sicily. Rome and Carthage had long been trading partners, and for centuries there was no real reason for them to be enemies since they were separated by the Mediterranean. That being said, as Rome’s power increased to encompass all of Italy, the Carthaginians became increasingly concerned that Rome might pose a threat to its own dominance.

Conflict finally broke out in 264 BCE in Sicily. The island of Sicily was one of the oldest and most important areas for Greek colonization. There, a war broke out between the two most powerful poleis, Syracuse and Messina. The Carthaginians sent a fleet to intervene on behalf of Messinans, but the Messinans then called for help from Rome as well (a betrayal of sorts from the perspective of Carthage). Soon, the conflict escalated as Carthage took the side of Syracuse and Rome saw an opportunity to expand Roman power in Sicily. The Centuriate Assembly voted to escalate the Roman military commitment since its members wanted the potential riches to be won in war. This initiated the First Punic War, which lasted from 264 to 241 BCE. (Note: “Punic” refers to the Roman term for Phoenician, and hence Carthage and its civilization.)

The Romans suffered several defeats, but they were rich and powerful enough at this point to persist in the war effort. Rome benefited greatly from the fact that the Carthaginians did not realize that the war could grow to be about more than just Sicily; even after winning victories there, the Carthaginians never tried to invade Italy itself (which they could have done, at least early on). The Romans eventually learned how to carry out effective naval warfare and stranded the Carthaginian army in Sicily. The Carthaginians sued for peace in 241 BCE and agreed to give up their claims to Sicily and to pay a war indemnity. Both states had suffered huge costs in both treasure and lives, which created a lasting hostility and bitterness between them. The Carthaginians were so financially strained that they failed to fully pay the numerous mercenary soldiers who had fought for them, leading to rebellions and further fighting within their territory. The Romans took advantage of this strife to seize the islands of Corsica and Sardinia as well, territories that were still under the nominal control of Carthage but which had been lost to their rebellious mercenaries.

From the aftermath of the First Punic War and the seizure of Sicily, Sardinia, and Corsica emerged the Roman provincial system: the islands were turned into “provinces” of the Republic, each of which was obligated to pay tribute (the “tithe,” meaning tenth, of all grain) and follow the orders of Roman governors appointed by the senate. That system would continue for the rest of the republican and imperial periods of Roman history, with the governors wielding enormous power and influence in their respective provinces.

Unsurprisingly, the Carthaginians wanted revenge, not just for their loss in the war but for Rome’s seizure of Corsica and Sardinia. For twenty years, the Carthaginians built up their forces and their resources, most notably by invading and conquering a large section of Spain, containing rich mines of gold and copper and thousands of Spanish Celts who came to serve as mercenaries in the Carthaginian armies. In 218 BCE, the great Carthaginian general Hannibal (son of the most successful general who had fought the Romans in the First Punic War) launched a surprise attack in Spain against Roman allies and then against Roman forces themselves. This led to the Second Punic War (218 BCE – 202 BCE).

Hannibal crossed the Alps into Italy from Spain with 60,000 men and a few dozen war elephants (most of the elephants perished, but the survivors proved very effective, and terrifying, against the Roman forces). For the next two years, he crushed every Roman army sent against him, killing tens of thousands of Roman soldiers and marching perilously close to Rome. Hannibal never lost a single battle in Italy, yet neither did he force the Romans to sue for peace.

Hannibal defeated the Romans repeatedly with clever tactics: he lured them across icy rivers and ambushed them, he concealed a whole army in the fog one morning and then sprang on a Roman legion, and he led the Romans into narrow passes and slaughtered them. In his most famous victory at Cannae in 216 BCE, Hannibal’s smaller army defeated a larger Roman force by letting it push in the Carthaginian center, then surrounding it with cavalry, completely trapping and massacring it. About 65,000 Roman soldiers were slaughtered, including both consuls, in one of the most one-sided and bloody battles in all of military history. He was hampered, though, by the fact that he did not have a siege train to attack Rome itself (which was heavily fortified), and he failed to win over the southern Italian cities which had been conquered by the Romans a century earlier. The Romans kept losing to Hannibal, but they were largely successful in keeping Hannibal from receiving reinforcements from Spain and Africa, slowly but steadily weakening his forces.

Eventually, the Romans altered their tactics and avoided fighting Hannibal within Italy, harrying his forces with a large army but refusing a pitched battle. This was totally contrary to their usual tactics, and the dictator Fabius Maximus who insisted on it in 217 BCE was mockingly nicknamed “the Delayer” by his detractors in the Roman government despite his evident success. The Romans vacillated on this strategy, suffering the terrible defeat mentioned above in 216 BCE, but as Hannibal’s victories grew and some cities in Italy and Sicily started defecting to the Carthaginian side, they returned to it.

A brilliant Roman general named Scipio defeated the Carthaginian forces back in Spain in 207 BCE, cutting Hannibal off from both reinforcements and supplies, which weakened his army significantly. Scipio then attacked Africa itself, forcing Carthage to recall Hannibal to protect the city. Hannibal finally lost in 202 BCE after coming as close as anyone had to defeating the Romans. The victorious Scipio, now easily the most powerful man in Rome, became Scipio “Africanus” – conqueror of Africa.

An uneasy peace lasted for several decades between Rome and Carthage, despite enduring anti-Carthaginian hatred in Rome; one prominent senator named Cato the Elder reputedly ended every speech in the Senate with the statement “…and Carthage must be destroyed.” Rome finally forced the issue in the mid-second century BCE by meddling in Carthaginian affairs. The third and last Punic War that ensued was utterly one-sided: it began in 149 BCE, and by 146 BCE Carthage was defeated. Not only were thousands of the Carthaginian people killed or enslaved, but the city itself was brutally sacked (the comment by Polybius regarding the terror inspired by Rome, noted above, was specifically in reference to the horrific sack of Carthage). The Romans created a myth to commemorate their victory, claiming that they had “plowed the earth with salt” at Carthage so that nothing would ever grow there again – that was not literally true, but it did serve as a useful legend as the Romans expanded their territories even further.

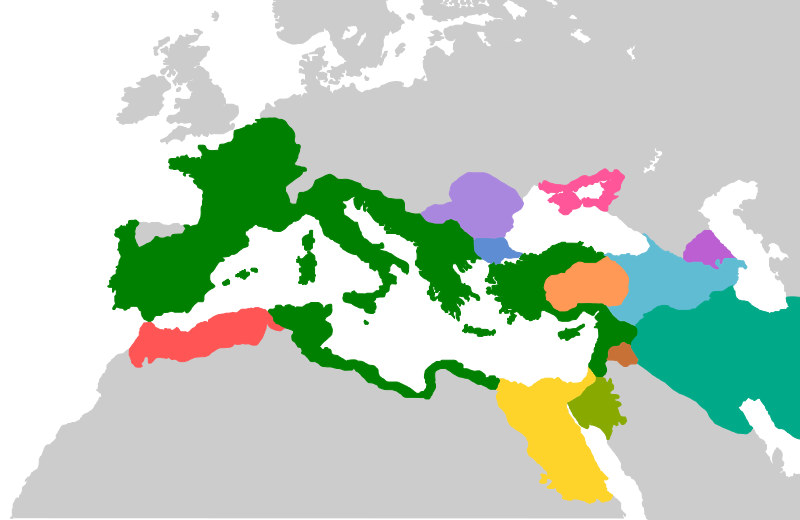

Greece

Rome expanded eastward during the same period, eventually conquering all of Greece, the heartland of the culture the Romans so admired and emulated. While Hannibal was busy rampaging around Italy, the Macedonian King Philip V allied with Carthage against Rome, a reasonable decision at the time because it seemed likely that Rome was going to lose the war. In 201 BCE, after the defeat of the Carthaginians, Rome sent an army against Philip to defend the independence of Greece and to exact revenge. There, Philip and the king of the Seleucid empire (named Antiochus III) had agreed to divide up the eastern Mediterranean, assuming they could defeat and control all of the Greek poleis. An expansionist faction in the Roman senate successfully convinced the Centuriate Assembly to declare war. The Roman legions defeated the Macedonian forces without much trouble in 196 BCE and then, perhaps surprisingly, they left, having accomplished their stated goal of defending Greek independence. Rome continued to fight the Seleucids for several more years, however, finally reducing the Seleucid king Antiochus III to a puppet of Rome.

Despite having no initial interest in establishing direct control in Greece, the Romans found that rival Greek poleis clamored for Roman help in their conflicts, and Roman influence in the region grew. Even given Rome’s long standing admiration for Greek culture, the political and military developments of this period, from 196 – 168 BCE, helped confirm the Roman belief that the Greeks were artistic and philosophical geniuses but, at least in their present iteration, were also conniving, treacherous, and lousy at political organization. There was also a growing conservative faction in Rome led by Cato the Elder that emphatically emphasized Roman moral virtue over Greek weakness.

Philip V’s son Perseus took the throne of Macedon in 179 BCE and, while not directly threatening Roman power, managed to spark suspicion among the Roman elite simply by reasserting Macedonian sovereignty in the region. In 172 BCE Rome sent an army and Macedon was defeated in 168 BCE. Rome split Macedon into puppet republics, plundered Macedon’s allies, and lorded over the remaining Greek poleis. Revolts in 150 and 146 against Roman power served as the final pretext for the Roman subjugation of Greece. This time, the Romans enacted harsh penalties for disloyalty among the Greek cities, utterly destroying the rich city of Corinth and butchering or enslaving tens of thousands of Greeks for siding against Rome. The plunder from Corinth specifically also sparked great interest in Greek art among elite Romans, boosting the development of Greco-Roman artistic traditions back in Italy.

Thus, after centuries of warfare, by 140 BCE the Romans controlled almost the entire Mediterranean world, from Spain to Anatolia. They had not yet conquered the remaining Hellenistic kingdoms, namely those of the Seleucids in the Near East and the Ptolemies in Egypt, but they controlled a vast territory nonetheless. Even the Ptolemies, the most genuinely independent power in the region, acknowledged that Rome held all the real power in international affairs.

The last great Hellenistic attempt to push back Roman control was in the early first century BCE, with the rise of a Greek king, Mithridates VI, from Pontus, a small kingdom on the southern shore of the Black Sea. Mithridates led a large anti-Roman coalition of Hellenistic peoples first in Anatolia and then in Greece itself starting in 88 BCE. Mithridates was seen by his followers as a great liberator from Roman corruption (one Roman governor had molten gold poured down his throat to symbolize the just punishment of Roman greed). He went on to fight a total of three wars against Rome, but despite his tenacity he was finally defeated and killed in 63 BCE, the same year that Rome extinguished the last pitiful vestiges of the Seleucid kingdom.

Under the leadership of a general and politician, Pompey (“the Great”), both Mithridates and the remaining independent formerly Seleucid territories were defeated and incorporated either as provinces or puppet states under the control of the Republic. With that, almost the entire Mediterranean region was under Rome’s sway – Egypt alone remained independent.

Greco-Roman Culture

The Romans had been in contact with Greek culture for centuries, ever since the Etruscans struck up their trading relationship with the Greek poleis of southern Italy. Initially, the Etruscans formed a conduit for trade and cultural exchange, but soon the Romans were trading directly with the Greeks as well as the various Greek colonies all over the Mediterranean. By the time the Romans finally conquered Greece itself, they had already spent hundreds of years absorbing Greek ideas and culture, modeling their architecture on the great buildings of the Greek Classical Age and studying Greek ideas.

Despite their admiration for Greek culture, there was a paradox in that Roman elites had their own self-proclaimed “Roman” virtues, virtues that they attributed to the Roman past, which were quite distinct from Greek ideas. Later authors summed up the Roman ideal with the term Romanitas, a catch-all term for the complicated virtues and expectations which Romans were expected to live up to. Roman virtues revolved around the idea that a Roman was courageous, reliable, honest, and prudent while the Greeks were (supposedly) shifty, untrustworthy, and incapable of effective political organization. The simple fact that the Greeks had been unable to forge an empire except during the brief period of Alexander’s conquests seemed to the Romans as proof that they did not possess an equivalent degree of virtue, and Romans credited the success of their state to their superior virtue compared to others. One of the most important Roman virtues, which indeed is the root for the English word ‘virtue’, was virtus. Virtus was based on the Roman word for man, Vir, but women could have virtus as well. It was a kind of driving ambition and competence: the ability to make things happen, to both seize the moment and to follow through relentlessly. The burning flame of virtus needed to be harnessed by disciplina and its attendant virtues, however: self-control, prudence, honesty, dignity and restraint was central to the virtuous Roman, whether man or woman. There was also a powerful theme of self-sacrifice associated with Romanitas – the ideal Roman would sacrifice himself for the greater good of Rome without hesitation. In some ways, Romanitas was the Romans’ spin on the old Greek combination of arete and civic virtue.

One example of Romanitas in action was the role of dictator. A Roman dictator, even more so than a consul, was expected to embody Romanitas, leading Rome through a period of crisis but then willingly giving up power. Since the Romans were convinced that anything resembling monarchy was politically repulsive, a dictator was expected to serve for the greater good of Rome and then step aside when peace was restored. Indeed, until the first century CE, dictators duly stepped down once their respective crises were addressed.

Romanitas was profoundly compatible with Greek Stoicism (which came of age in the Hellenistic monarchies just as Rome itself was expanding). Stoicism celebrated self-sacrifice, strength, political service, and the rejection of frivolous luxuries; these were all ideas that seemed laudable to Romans. By the first century BCE, Stoicism was the Greek philosophy of choice among many aristocratic Romans (a later Roman emperor, Marcus Aurelius, was even a Stoic philosopher in his own right).

The implications of Romanitas for political and military loyalty and morale are obvious. One less obvious expression of Romanitas, however, was in public building and celebrations. One way for elite (rich) Romans to express their Romanitas was to fund the construction of temples, forums, arenas, or practical public works like roads and aqueducts. Likewise, elite Romans would often pay for huge games and contests with free food and drink, sometimes for entire cities. This practice was not just in the name of showing off; it was an expression of one’s loyalty to the Roman people and their shared Roman culture. The creation of numerous Roman buildings (some of which survive) is the result of this form of Romanitas.

Despite their tremendous pride in Roman culture, the Romans still found much to admire about Greek intellectual achievements. By about 230 BCE, Romans started taking an active interest in Greek literature. Some Greek slaves were true intellectuals who found an important place in Roman society. One status symbol in Rome was to have a Greek slave who could tutor one’s children in the Greek language and Greek learning. In 220 BCE a Roman senator, Quintus Fabius Pictor, wrote a history of Rome in Greek, the first major work of Greek literature written by a Roman (like so many ancient sources, it has not survived). Soon, Romans were imitating the Greeks, writing in both Greek and Latin and creating poetry, drama, and literature.

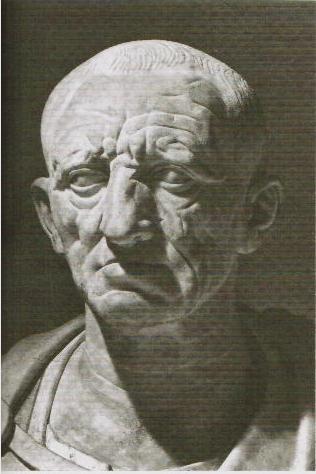

That being noted, the interest in Greek culture was muted until the Roman wars in Greece that began with the defeat of Philip V of Macedon. Rome’s Greek wars created a kind of “feeding frenzy” of Greek art and Greek slaves. Huge amounts of Greek statuary and art were shipped back to Rome as part of the spoils of war, having an immediate impact on Roman taste. The appeal of Greek art was undeniable. Greek artists, even those who escaped slavery, soon started moving to Rome en masse because there was so much money to be made there if an artist could secure a wealthy patron. Greek artists, and the Romans who learned from them, adapted the Hellenistic Greek style. In many cases, classical statues were recreated exactly by sculptors, somewhat like modern-day prints of famous paintings. In others, a new style of realistic portraiture in sculpture that originated in the Hellenistic kingdoms proved irresistible to the Romans; whereas the Greeks of the Classical Age usually idealized the subjects of art, the Romans came to prefer more realistic and “honest” portrayals. We know precisely what many Romans looked like because of the realistic busts made of their faces: wrinkles, warts and all.

Along with philosophy and architecture, the most important Greek import to arrive on Roman shores was rhetoric: the mastery of words and language in order to persuade people and win arguments. The Greeks held that the two ways a man could best his rivals and assert his virtue were battle and public discussion and argumentation. This tradition was felt very keenly by the Romans, because those were precisely the two major ways the Roman Republic operated – the superiority of its armies was well-known, while individual leaders had to be able to convince their peers and rivals of the correctness of their positions. The Romans thus very consciously tried to copy the Greeks, especially the Athenians, for their skill at oratory.

Not surprisingly, the Romans both admired and resented the Greeks for the Greek mastery of words. The Romans came to pride themselves on a more direct, less subtle form of oratory than that (supposedly) practiced in Greece. Part of Roman oratorical skill was the use of passionate appeals to emotional responses in the audience, ones that were supposed to both harness and control the emotions of the speaker himself. The Romans also formalized instruction in rhetoric, a practice of studying the speeches of great speakers and politicians of the past and of debating instructors and fellow students in mock scenarios.

Roman Society

Patriarchy and the Paterfamilias

Family life was oriented around the paterfamilias, the male head of the household. According to tradition, this patriarch had the power of life and death over all his dependents, an authority referred to as patria potestas (“paternal power”). Members of the extended family subject to this authority included the patriarch’s wife, their children, anyone descended through the family’s male line, and all enslaved people belonging to the household. With his authority, the patriarch was both the judge and rule maker of the family, with the power to sell his dependents into bondage or destroy their property. This authority was justified by widespread Roman beliefs about the generally superior judgement and rationality of men over women and older men over younger ones.

Ultimately, however, the goal of the paterfamilias was to promote his family’s welfare. His power worked through consensus and deliberation with the other family members. As the primary provider, he expected respect from his family but could also reward good behavior. In this way, an entire family might benefit by working together to further their social or financial prosperity. All members in the family jointly benefited from the status and wealth that the family accumulated, and consequently Roman society had a ‘clannish’ nature, where close relatives typically supported one another over outsiders. After the death of the paterfamilias, any adult male children who had their own residences would become the heads of their own families, new paterfamilias. If the father had died without a will, his property would be divided among all his surviving children (both male and female), but this was rare. Usually a will would designate an heir who would receive all property and debts except for any seperate bequests to other people, often including important clients (see below).

The securing of a Roman family’s reputation began with the education and training of children. In early Rome, children were educated in the home; later, grammar schools enrolled boys and girls from wealthy families until around the age of twelve. Education usually centered on reading and writing Latin and Greek as well as arithmetic. Many Roman women were well educated, particularly those from aristocratic backgrounds, and education for both sexes was seen in a positive light within Roman culture. Around age fifteen, boys donned the toga virilis (“toga of manhood”), a plain white toga representing their enrollment as citizens and entrance into manhood. Roman citizenship was highly coveted and was bestowed either at birth to children of citizens or by special decree. Sons of prominent families could then go on to a civil or military career. After a son inherited his father’s property (as well as his debts), it became his responsibility to maintain the family’s reputation and prosperity.

By contrast, girls commonly married at a young age, usually between fourteen and eighteen years old, and often to a much older man. Younger girls were viewed as mature enough to take on motherhood and household management, and men between the ages of 15 and 25 were seen as immature and unready for important responsibilities. The importance of the paternal lineage also made it important to Romans for women to be virginal when first married. In the most common form of marriage, a wife brought a dowry that became her husband’s property. Thus, a woman from a wealthy background with a large dowry had some sway in making marriage arrangements. Women could also be married sine manu, which mean that the wife was still under the technical authority of her father, not her husband. This gave the wife more autonomy in her marriage, as her husband did not have the same degree of direct legal power over her and it did not automatically confer all her property to her husband.

The vast legal and age imbalance between husband and wife was reflected in the cultural restrictions on Roman women. Yet, though a Roman man’s work was an important contributor to the family’s success, women devoted much of their efforts to the same goal. Women were responsible for the management of the household, which included ensuring provisions for the family, overseeing any enslaved people and other dependent, and looking after the children. Spinning wool was viewed as the activity of an ideal Roman woman, and many wives were expected to occupy themselves with this work, which was an indispensable economic task that required huge quantities of labour. However, the Roman ideal of family life we see discussed by Roman authors was an aristocratic one, and the lives of ordinary Romans were very different from the villa-inhabiting, slave owning authors that give us our window into the Roman world. We have little direct insight into the lives even of ordinary Roman farming families, let alone families of landless proletarii or slaves. Most women did not live the way that Roman elites thought they should, there is evidence that many ordinary women held professions outside the home, including in medicine, trade, and agriculture.

Similarily, despite the legal requirement for women to be represented by men and always under the authority of a parent, husband or sibling, there is ample evidence of women operating businesses, running estates, and employing workers. Under Augustus in the early empire, some new legal avenues for women’s autonomy were also opened, even as Augustus tried to reinforce the traditional family and encourage women to be mothers. Women who had birthed three children, or former slaves who had birthed four, were allowed to own property and engage in lawsuits without the need for a male guardian. Some women also lived entirely outside the bounds of respectability as prostitutes, actors, dancers, or even gladiators.

Clientage and Hierarchy

Much of Roman social life revolved around the system of clientage. Clientage consisted of networks of “patrons” – people with power and influence – and their “clients” – those who looked to the patrons for support. A patron would do things like arrange for his or her (i.e. there were women patrons, not just men) clients to receive lucrative government contracts, to be appointed as officers in a Roman legion, to be able to buy a key piece of farmland, and so on. In return, the patron would expect political support from their clients by voting as directed in the Centuriate or Plebeian Assembly, by influencing other votes, and by blocking political rivals. Likewise, clients who shared a patron were expected to help one another. These were open, publicly-known alliances rather than hidden deals made behind closed doors; groups of clients would accompany their patron into meetings of the senate or assemblies as a show of strength.

The government of the late Republic was still in the form of the Plebeian Assembly, the Centuriate Assembly, the Senate, ten tribunes, two consuls, and a court system under formal rules of law. By the late Republic, however, a network of patrons and clients had emerged that largely controlled the government. Elite families of nobles, through their client networks, made all of the important decisions. Beneath this group were the equestrians: families who did not have the ancient lineages of the patricians and who normally did not serve in public office. The equestrians, however, were rich, and they benefited from the fact that senators were formally banned from engaging in commerce as of the late third century BCE. They constituted the business class of Republican Rome who supported the elites while receiving various trade and mercantile concessions.

This created an ongoing problem for Rome, one that was exploited many times by populist leaders: Rome relied on a free class of citizens to serve in the army, but those same citizens often had to struggle to make ends meet as farmers. As the rich grew richer, they bought up land and sometimes even forced poorer citizens off of their farms. Thus, there was an existential threat to Rome’s armies, and with it, to Rome itself. In the late Republic, ambitious generals such as Marius solved this problem by recruiting poor, landless Romans to their armies. These men relied on their patron general to provide them with rewards for their service, especially the promise of land or the veterans after they retired. This meant that such soldiers owed their loyalty more to their general than to the Roman state, which made civil war much more likely.

A comparable status hierarchy existed in the territories – soon provinces – conquered in war. Rome was happy to grant citizenship to local elites who supported Roman rule, and sometimes entire communities could be granted citizenship on the basis of their loyalty (or simply their perceived usefulness) to Rome. Citizenship was a useful commodity, protecting its holders from harsher legal punishments and affording them significant political rights. Most Roman subjects, however, were just that: subjects, not citizens. In the provinces they were subject to the goodwill of the Roman governor, who might well look for opportunities to extract provincial wealth for his own benefit.

Slavery

At the bottom of the Roman social system were the slaves. Slaves were one of the most lucrative forms of loot available to Roman soldiers, and so many lands had been conquered by Rome that the population of the Republic was swollen with slaves. Fully one-third of the population of Italy were slaves by the first century CE. Even freed slaves, called freedmen, had limited legal rights and had formal obligations to serve their former masters as clients. Roman slaves spanned the same range of jobs noted with other slaveholding societies like the Greeks: elite slaves lived much more comfortably than did most free Romans, but most were laborers or domestic servants. All could be abused by their owners without legal consequence.

Slavery was a huge economic engine in Roman society. Much of the “loot” seized in Roman campaigns was made up of human beings, and Roman soldiers were eager to capitalize on captives they took by selling them on returning to Italy. In historical hindsight, however, slavery may have undermined both Roman productivity and the pace of innovation in Roman society. There was less incentive to innovate technologically or invest in large projects such as watermills because slave labor was always available. Also, the long-term effect of the growth of slavery in Rome was to undermine the social status of free Roman citizens, with farmers in particular struggling to survive as rich Romans purchased land and built huge slave plantations.

There were many slave uprisings, the most significant of which was led by Spartacus, a gladiator (warrior who fought for public amusement) originally from Thrace. Spartacus led the revolt of his gladiatorial school in the Italian city of Capua in 73 BCE. He set up a war camp on the slopes of the volcano Mt. Vesuvius, to which thousands of slaves fled, culminating in an “army” of about 70,000. He tried to convince them to flee over the Alps to seek refuge in their (mostly Celtic) homelands, but was eventually convinced to turn around to plunder Italy. The richest man in Italy, the senator Crassus, took command of the Roman army assembled to defeat Spartacus, crushing the slave army and killing Spartacus in 71 BCE (and lining the road to Rome with 6,000 crucified slaves).

Gender Roles

Rome offered greater freedom and autonomy to women than did some of its neighboring societies (like Greece). While Roman culture was explicitly patriarchal with families organized under the authority of the paterfamilias, there is a great deal of textual evidence that suggests that women enjoyed considerable independence nevertheless. Women retained the ownership of their dowries at marriage, could initiate divorce, and controlled their own inheritances. Widows, who were common thanks to the young marriage age of women and the death of soldier husbands, were legally autonomous and continued to run households after the death of the husband. Within families, women’s voices carried considerable weight, and in the realm of politics, while men held all official positions, women exercised considerable influence from behind the scenes.

Roman culture celebrated the devoted mother and wife as the female ideal, and Roman traditionalists decried the loosening of strict gender roles that seems to have taken place over time during the Republic. Women were expected to be frugal managers of households and, in theory, they were to avoid ostentatious displays. Likewise, Roman law explicitly designated men as the official decision-makers within the family unit. That being noted, however, one of the reasons that we know that women did enjoy a higher degree of autonomy than in many other societies is the number of surviving texts that both described and, in many cases, celebrated the role of women. Those texts were written by both men and women, and most Romans (men very much included) felt that it was both appropriate and desirable for both boys and girls to be properly educated.

All of this took place, however, in a context that assumed women were fundamentally inferior to men as measured by the virtues associated with Romanitas. Women were, as in Greece, identified with the body, seen as less rational and easily ruled by their desires and appetites. Women and men were judged by somewhat similar standards, in that a courageous, prudent, dignified and pious woman could be recognized and celebrated as such. However, any person’s gender deeply shaped the way that Romans would expect them to behave and judge their actions. Furthermore the deep Roman respect for tradition and the accepted way of doing things meant that the status of women and men in society were very deeply embedded and difficult to change in the culture. Women were by tradition barred from formal authority, expected to be married young, and under the power of men in their lives. Such expectations were almost impossible to evade or even question in Roman society.

This chapter is partly adapted from

Western Civilization: A Concise History by Christopher Brooks and is used under a CC BY-NC-SA 4.0 license.

World History, Volume 1 by openstax.org, used under a CC-BY 4.0 license.

Media Attributions

7.1 Romulus and Remus by Stinkzwam is licensed under CC BY-SA 3.0

7.2 Expansion of the Republic by Javierfv1212, in the public domain

7.3 Punic Wars byJavierfv1212, in the public domain

7.4 Mithridates VI by Eric Gaba is licensed under CC BY-SA 2.5

7.5 Map of the Republic by Alvaro qc is licensed under CC BY 2.5

7.6 Patrician Torlonia by unknown author, in the public domain

Feedback/Errata