4 City States and Ancient Greece

Magna Graeca

The Cup of Nestor

Sometime in the eighth century BCE, an aristocratic resident of the Greek trading colony of Pithekoussai—located on the tiny island of Ischia just off the coast of Naples in Italy—held a symposium at his home. Most of what happened at the party stayed at the party, but what we do know is that it must have been a good one. One of the guests, presumably operating under the influence of his host’s excellent wine, took the liberty of scratching the following ditty onto one of his host’s fine exported ceramic wine cups: “I am the Cup of Nestor, good to drink from. Whoever drinks from this cup, straightaway the desire of beautifully-crowned Aphrodite will seize him.”

While party pranks do not commonly make history, this one has: this so-called Cup of Nestor is one of the earliest examples of writing in the Greek alphabet, as well as the earliest known written reference to the Homeric epics. Overall, this cup and the inscription on it exemplify the mobility of the Ancient Greeks and their borrowing of skills and culture from others around the Mediterranean while, at the same time, cultivating a set of values specific to themselves. The cup itself had been brought across the wine-dark sea from the island of Euboea by a merchant, pirate, or traveller. The new script, in which the daring guest wrote on the cup, had just recently been borrowed and adapted by the Greeks from the Phoenicians, a seafaring nation based in modern-day Lebanon. Indeed, our clever poet wrote from right to left, just like the Phoenicians. Finally, the poem mentions Nestor, one of the heroes of Homer’s Iliad, an epic about the Trojan War, and a source of common values that all Greeks held dear: competitive excellence on both the battlefield and in all areas of everyday life, and a sense of brotherhood that manifested itself most obviously in the shared language of all the Greeks. That feeling of kinship facilitated collaboration of all the Greeks in times of crisis from the mythical Trojan War to the Persian Wars, and finally, during the Greeks’ resistance against the Roman conquest.

The Greek poleis were each distinct, fiercely proud of their own identity and independence, and they frequently fought small-scale wars against one another. Even as they did so, they recognized each other as fellow Greeks and therefore as cultural equals. All Greeks spoke mutually intelligible dialects of the Greek language. All Greeks worshiped the same pantheon of gods. All Greeks shared political traditions of citizenship. Finally, the Greeks took part in a range of cultural practices, from listening to traveling storytellers who recited the Iliad and Odyssey from memory to holding drawn-out drinking parties called symposia, such as the one where the cup of Nestor was inscribed.

The poleis also invented institutions that united the cities culturally, despite their political independence, the most important of which was the Panhellenic games. “Panhellenic” literally means “all Greece,” and the games were meant to unite all of the Greek poleis, including those founded by colonists and located far from Greece itself. The games were a combination of religious festival and competition in which aristocrats from each city competed in various sports, including javelin, discus, footraces, and a brutal form of unarmed combat called pankration.

The most significant of these games was the Olympics, named after Olympia, the site in southern Greece where they were held every four years. They started in 776 BCE and ended in 393 CE – in other words, they lasted for over 1,000 years. Thanks to the Olympics, the date 776 BCE is usually used as the definitive break between the Dark and Archaic ages of Greek civilization. The Olympics were extraordinary not just in their longevity, but because Greeks from the entire world of Greek settlements came to them, traveling from as far away as Sicily and the Black Sea. Wars were temporarily suspended and all Greek poleis agreed to let athletes travel with safe passage to take part in the games, in part because the Olympics were dedicated to Zeus, the chief Greek god. There were no second place prizes and no medals: the winner of each competition was crowned with a wreath made of laurel leaves, but more importantly gained the fame, or kudos, that was spread far and wide throughout Greece. The kudos of many of these athletes has survived to the present day via inscriptions, giving them a kind of social immortality that the Greeks craved and celebrated. Greek culture was hugely competitive; the defeated were humiliated and the winners revelled in the ecstasy of triumph. In the games, they sought, in the words of one Greek poet, “either the wreath of victory or death”, (they did not literally seek death if defeated, that is poetic exaggeration).

With the end of the Dark Age, population levels in Greece recovered. This led to emigration as the population outstripped the poor, rocky soil of Greece itself and forced people to move elsewhere. Eventually, Greek colonies stretched across the Mediterranean as far as Spain in the west and the coasts of the Black Sea in the north. Greeks founded colonies on the North African coast and on the islands of the Mediterranean, most importantly on Sicily. Greeks set up trading posts in the areas they settled, even in Egypt. The colonies continued the mainland practice of growing olives and grapes for oil and wine, but they also took advantage of much more fertile areas away from Greece to cultivate other crops.

Greek colonists sometimes intermarried with local peoples on arrival, an unsurprising practice given that many expeditions of colonists were almost all young men. In other cases, colonists found relatively isolated areas appropriate for shipping and maintained close connections with their home polis as an economic outpost. The one factor that was common to all Greek colonies was that they were rarely far from the sea. They were so closely tied to the idea of a shared Greek civilization and the need for the sea for trade routes was so strong that colonists were not generally interested in trying to push inland. Often Greek colonies had tense relations with nearby rural, tribal populations that had inhabited the area from long before.

As trade recovered following the end of the Dark Age, the Greeks re-established their commercial shipping network across the Mediterranean, with their colonies soon playing a vital role. Greek merchants eagerly traded with everyone from the Celts of Western Europe to the Egyptians, Lydians, and Babylonians. When Julius Caesar was busy conquering Gaul about 700 years later, he found the Celts there writing in the Greek alphabet, long since learned from the Greek colonies along the coast. Likewise, archaeologists have discovered beautiful examples of Greek metalwork as far from Greece as northern France.

Greek colonies far from Greece were as important as the older poleis in Greece itself, since they created a common Greek civilization across the entire Mediterranean world. Greek civilization was not an empire united by a single ruler or government. Instead, it was united by culture rather than a common leadership structure. That culture would go on to influence all of the cultures to follow in a vast swath of territory throughout the Mediterranean region and the Middle East.

Historians today separate Greek history into particular periods, which shared specific features throughout the Greek world:

The Bronze Age (c. 3,300 – 1,150 BCE) – a period characterized by the use of bronze tools and weapons. In addition, two particular periods during the Bronze Age are crucial in the development of early Greece: the Minoan Age on the island of Crete (c. 2,000 – 1,450 BCE) and the Mycenean period on mainland Greece (c. 1,600 – 1,100 BCE), both of them characterized by massive palaces, remnants of which still proudly stand today. The Minoan and Mycenaean civilizations had writing (dubbed Linear A and Linear B, respectively), which they used for keeping lists and palace inventories.

The Dark Ages (c. 1,100 – 700 BCE) – a period that is “dark” from the archaeological perspective, which means that the monumental palaces of the Mycenean period disappear, and the archaeological record reveals a general poverty and loss of culture throughout the Greek world. For instance, the Linear A and Linear B writing systems disappear. The Greeks do not rediscover writing until the invention of the Greek alphabet at the end of the Dark Ages or the early Archaic Period.

Archaic Period (c. 700 – 480 BCE) – the earliest period for which written evidence survives; this is the age of the rise of the Greek city-states, colonization, and the Persian Wars.

Classical Period (c. 480 – 323 BCE) – the period from the end of the Persian Wars to the death of Alexander the Great. One of the most important events during this period is the Peloponnesian War (431 – 404 BCE), which pitted Athens against Sparta, and forced all other Greek city-states to choose to join one side or the other. This period ends with the death of Alexander the Great, who had unified the Greek world into a large kingdom with himself at its helm.

Hellenistic Period (323 – 146 BCE) – the period from the death of Alexander to the Roman conquest of Greece; this is the age of the Hellenistic monarchies ruling over territories previously conquered by Alexander and his generals. Some historians end this period in 30 BCE, with the death of Cleopatra VII, the last surviving ruler of Egypt who was a descendant of one of Alexander’s generals.

FROM MYTHOLOGY TO HISTORY

The terms “mythology” and “history” may seem, by modern definitions, to be antithetical. After all, mythology refers to stories that are clearly false, of long-forgotten gods and heroes and their miraculous feats. History, on the other hand, refers to actual events that involved real people. And yet, the idea that the two are opposites would have seemed baffling to a typical resident of the ancient Mediterranean world. Rather, gods and myths were part of the everyday life, and historical events could become subsumed by myths just as easily as myths could become a part of history. For instance, Gilgamesh, the hero of the Sumerian Epic of Gilgamesh, was a real king of Uruk, yet he also became the hero of the epic. Each Greek city-state, in particular, had a foundation myth describing its origins as well as its own patron gods and goddesses. Etiological myths, furthermore, served to explain why certain institutions or practices existed; for instance, the tragic trilogy Oresteia of the Athenian poet Aeschylus tells the myth explaining the establishment of the Athenian murder courts in the Classical period.

Yet, while the Greeks saw mythology and history as related concepts and sometimes as two sides of the same coin, one specific mythical event marked, in the eyes of the earliest known Greek historians, the beginning of the story of Greek-speaking peoples. That event was the Trojan War.

Homer and the Trojan War

It is telling that the two earliest Greek historians, Herodotus, writing in the mid-fifth century BCE, and Thucydides, writing in the last third of the fifth century BCE, each began their histories with the Trojan War, treating it as a historical event. The Homeric epics Iliad and Odyssey portray the war as an organized attack of a unified Greek army against Troy, a city in Asia Minor (see map 4.1). The instigating offense? The Trojan prince Paris kidnapped Helen, the most beautiful woman in the world, from her husband Menelaus, king of Sparta. This slight to Menelaus’ honor prompted Menelaus’ brotherAgamemnon, king of Mycenae, to raise an army from the entire Greek world and sail to Troy. The mythical tradition had it that after a brutal ten-year siege, the Greeks resorted to a trick: they presented the Trojans with a hollow wooden horse, filled with armed soldiers. The Trojans tragically accepted the gift, ostensibly intended as a dedication to the goddess Athena. That same night, the warriors emerged from the horse, and the city finally fell to the Greeks. Picking up the story ten years after the end of the Trojan War, the Odyssey then told the story of Odysseus’s struggles to return home after the war and the changes that reverberated throughout the Greek world after the fall of Troy.

The Homeric epics were the foundation of Greek education in the Archaic and Classical periods and, as such, are a historian’s best source of pan-Hellenic values. A major theme throughout both epics is personal honor, which Homeric heroes value more than the collective cause. For example, when Agamemnon slights Achilles’ honor in the beginning of the Iliad, Achilles, the best hero of the Greeks, withdraws from battle for much of the epic, even though his action causes the Greeks to start losing battles until he rejoins the fight. A related theme is competitive excellence, with kleos (eternal glory) as its goal: all Greek heroes want to be the best; thus, even while fighting in the same army, they see each other as competition. Ultimately, Achilles has to make a choice: he can live a long life and die unknown, or he can die in battle young and have everlasting glory. Achilles’ selection of the second option made him the inspiration for such historical Greek warriors and generals as Alexander the Great, who brought his scroll copy of the Iliad with him on all campaigns. Finally, the presence of the gods in the background of the Trojan War shows the Greeks’ belief that the gods were everywhere, and acted in the lives of mortals. These gods could be powerful benefactors and patrons of individuals who respected them and sought their favor, or vicious enemies, bent on destruction. Indeed, early in the Iliad, the god Apollo sends a plague on the Greek army at Troy, as punishment for disrespecting his priest.

It is important to note that while the Homeric epics influenced Greek values from the Archaic period on, they do not reflect the reality of the Greek world in any one period. Furthermore, they were not composed by a single poet, Homer; indeed, it is possible that Homer never existed. Because the epics were composed orally by multiple bards over the period of several hundred years, they combine details about technological and other aspects of the Bronze Age with those of the Dark Ages and even the early Archaic Age. For instance, the heroes use bronze weapons side-by-side with iron. Archaeological evidence, however, allows historians to reconstruct to some extent a picture of the Greek world in the Bronze Age and the Dark Ages.

Greece in the Bronze Age, and the Dark Ages

While there were people living in mainland Greece already in the Neolithic Period, historians typically begin the study of the Greeks as a unique civilization in the Bronze Age, with the Minoans. The first literate civilization in Europe, the Minoans were a palace civilization that flourished on the island of Crete c. 2,000 – 1,450 BCE.

As befits island-dwellers, they were traders and seafarers; indeed, the Greek historian Thucydides credits them with being the first Greeks to sail on ships. Sir Arthur Evans, the archaeologist who first excavated Crete in the early 1900s, dubbed them Minoans, after the mythical Cretan king Minos who was best known for building a labyrinth to house the Minotaur, a monster that was half-man, half-bull. Bulls appear everywhere in surviving Minoan art, suggesting that they indeed held a prominent place in Minoan mythology and religion.

Four major palace sites survive on Crete. The most significant of them, Knossos, has been restored and reconstructed for the benefit of modern tourists.

Historians hypothesize that the palaces were the homes of local rulers, who ruled and protected the surrounding farmland. The palaces seem to have kept records in two different writing systems, the earliest known in Europe: the Cretan hieroglyphic and Linear A scripts. Unfortunately, neither of these systems has been deciphered, but it is likely that these were palace inventories and records pertaining to trade. The palaces had no surrounding walls, suggesting that the Cretans maintained peace with each other and felt safe from outside attacks, since they lived on an island. This sense of security proved to be a mistake as, around 1,450 BCE, the palaces were violently destroyed by invaders, possibly the Mycenaeans who arrived from mainland Greece. Recent discoveries also suggest that at least some of the destruction may have been the result of tsunamis which accompanied the Santorini/ Thera volcanic eruption in the 1600s BCE.

The Bull-Leaping Fresco from Knossos

Author: User “Jebulon”

Source: Wikimedia Commons

License: CC0 1.0

The Mycenaeans, similarly to the Minoans, were a palace civilization. Flourishing on mainland Greece c. 1,600 – 1,100 BCE, they received their name from Mycenae, the most elaborate surviving palace and the mythical home of Agamemnon, the commander-in- chief of the Greek army in the Trojan War. The archaeological excavations of graves in Mycenae reveal a prosperous civilization that produced elaborate pottery, bronze weapons and tools, and extravagant jewelry and other objects made of precious metals and gems. One of the most famous finds is the so-called “Mask of Agamemnon,” a burial mask with which one aristocrat was buried, made of hammered gold. The Mycenaeans also kept palace records in a syllabic script, known as Linear B. Related to the Cretan Linear A script, Linear B, however, has been deciphered, and identified as Greek.

Reconstructed North Portico at Knossos

Author: User “Bernard Gagnon”

Source: Wikimedia Commons

License: CC BY-SA 3.0

Archaeological evidence also shows that sometime in the 1,200s BCE, the Mycenaean palaces suffered a series of attacks and were gradually abandoned over the next century. The period that begins around 1,000 BCE is known as the “Dark Ages” because of the notable decline, in contrast with the preceding period. The Mycenaean Linear B script disappears, and archaeological evidence shows a poorer Greece with a decline in material wealth and life expectancy. Some contact, however, must have remained with the rest of the Mediterranean, as shown by the emergence of the Greek alphabet, adapted from the Phoenician writing system towards the end of the Dark Ages or early in the Archaic Period.

Figure 5.8 | Mask of Agamemnon, Mycenae

Author: User “Xuan Che”

Source: Wikimedia Commons

License: CC BY 2.0

ARCHAIC GREECE

The story of the Greek world in the Dark Ages could mostly be described as a story of fragmentation. With a few exceptions, individual sites had limited contact with each other. The Archaic period, however, appears to have been a time of growing contacts and connections between different parts of mainland Greece. Furthermore, it was a time of expansion, as the establishment of overseas colonies and cities brought the Greeks to Italy and Sicily in the West, and Asia Minor and the Black Sea littoral in the East. Furthermore, while Greeks in the Archaic period saw themselves as citizens of individual city-states, this period also witnessed the rise of a Pan-Hellenic identity, as all Greeks saw themselves connected by virtue of their common language, religion, and Homeric values. This Pan-Hellenic identity was ultimately cemented during the Persian Wars: two invasions of Greece by the Persian Empire at the end of the Archaic period.

Figure 5.9 | Comparative chart of writing systems in the Ancient Mediterranean | As this chart shows, in addition to the influence of the Phoenician alphabet on the Greek, there were close connections between the Phoenician, Egyptian, and Hebrew writing systems as well.

Author: Samuel Prideaux Tregelles

Source: Google Books

License: Public Domain

Rise of the Hoplite Phalanx and the Polis

A Corinthian vase, known today as the Chigi Vase, made in the mid-seventh century BCE, presents a tantalizing glimpse of the changing times from the Dark Ages to the Archaic Period. Taking up much of the decorated space on the vase is a battle scene. Two armies of warriors with round shields, helmets, and spears are facing each other and appear to be marching in formation towards each other in preparation for attack.

Modern scholars largely consider the vase to be the earliest artistic portrayal of the hoplite phalanx, a new way of fighting that spread around the Greek world in the early Archaic Age and that coincided with the rise of another key institution for subsequent Greek history: the polis, or city-state. From the early Archaic period to the conquest of the Greek world by Philip and Alexander in the late fourth century BCE, the polis was the central unit of organization in the Greek world.

While warfare in the Iliad consisted largely of duels between individual heroes, the hoplite phalanx was a new mode of fighting that did not rely on the skill of individuals. Rather, it required all soldiers in the line to work together as a whole. Armed in the same way with a helmet, spear, and the round shield, the hoplon, which gave the hoplites their name – the soldiers were arranged in rows, possibly as much as seven deep. Each soldier carried his shield on his left arm, protecting the left side of his own body and the right side of his comrade to the left. Working together as one, then, the phalanx would execute the othismos (a mass shove) during battle, with the goal of shoving the enemy phalanx off the battlefield.

Figure 5.10 | “Unrolled” reconstructed image from the Chigi Vase

Author: User “Phokion”

Source: Wikimedia Commons

License: CC BY-SA 4.0

Historians do not know which came into existence first, the phalanx or the polis, but the two clearly reflect a similar ideology. In fact, the phalanx could be seen as a microcosm of the polis, exemplifying the chief values of the polis on a small scale. Each polis was a fully self-sufficient unit of organization, with its own laws, definition of citizenship, government, army, economy, and local cults. Regardless of the differences between the many poleis in matters of citizenship, government, and law, one key similarity is clear: the survival of the polis depended on the dedication of all its citizens to the collective well-being of the city-state. This dedication included service in the phalanx. As a result, citizenship in most Greek city-states was closely connected to military service, and women were excluded from citizenship. Furthermore, since hoplites had to provide their own armor, these citizen-militias effectively consisted of landowners. This is not to say, though, that the poorer citizens were entirely excluded from serving their city. One example of a way in which they may have participated even in the phalanx appears on the Chigi Vase. Marching between two lines of warriors is an unarmed man, playing a double-reed flute (seen on the right end of the top band in Figure 5.10). Since the success of the phalanx depended on marching together in step, the flute-player’s music would have been essential to ensure that everyone kept the same tempo during the march. Poorer citizens could also fight as skirmishers, with javelins and light shields, and the navies of the city-states were largely crewed by poor rowers paid a wage for their service. Many hoplites also were accompanied by an attendant to help carry their equipment and provisions, often a slave.

Greek Religion

One theory modern scholars have proposed for the rise of the polis connects the locations of the city-states to known cult-sites. The theory argues that the Greeks of the Archaic period built city-states around these precincts of various gods in order to live closer to them and protect them. While impossible to know for sure if this theory or any other regarding the rise of the polis is true, the building of temples in cities during the Archaic period shows the increasing emphasis that the poleis were placing on religion.

It is important to note that Greek religion seems to have been, at least to some extent, an element of continuity from the Bronze Age to the Archaic period and beyond. The important role that the gods play in the Homeric epics attests to their prominence in the oral tradition, going back to the Dark Ages. Furthermore, names of the following major gods worshipped in the Archaic period and beyond were found on the deciphered Linear B tablets: Zeus, king of the gods and god of weather, associated with the thunderbolt; Hera, Zeus’ wife and patroness of childbirth; Poseidon, god of the sea; Hermes, messenger god and patron of thieves and merchants; Athena, goddess of war and wisdom and patroness of women’s crafts; Ares, god of war; Dionysus, god of wine; and the twins Apollo, god of the sun and both god of the plague and a healer, and Artemis, goddess of the hunt and the moon. All of these gods continued to be the major divinities in Greek religion for its duration, and many of them were worshipped as patron gods of individual cities, such as Artemis at Sparta, and Athena at Athens.

While many local cults of even major gods were truly local in appeal, a few local cults achieved truly Pan-Hellenic appeal. Drawing visitors from all over the Greek world, these Pan-Hellenic cults were seen as belonging equally to all the Greeks. One of the most famous examples is the cult of Asclepius at Epidaurus. Asclepius, son of Apollo, was a healer god, and his shrine at Epidaurus attracted the pilgrims from all over the Greek world. Visitors suffering from illness practiced incubation, that is, spending the night in the temple, in the hopes of receiving a vision in their dreams suggesting a cure. In gratitude for the god’s healing, some pilgrims dedicated casts of their healed body parts. Archaeological findings include a plentitude of ears, noses, arms, and feet. Starting out as local cults, several religious festivals that included athletic competitions as part of the celebration also achieved Pan-Hellenic prominence during the Archaic period. The most influential of these were the Olympic Games. Beginning in 776 BCE, the Olympic Games were held in Olympia every four years in honor of Zeus; they drew competitors from all over the Greek world, and even Persia. The Pan-Hellenic appeal of the Olympics is signified by the impact that these games had on Greek politics: for instance, a truce was in effect throughout the Greek world for the duration of each Olympics. In addition, the Olympics provided a Pan-Hellenic system of dating events by Olympiads or four-year cycles.

Figure 5.11 | Themis and Aegeus | The Pythia seated on the tripod and holding a laurel branch – symbols of Apollo, who was the source of her prophecies. This is the only surviving image of the Pythia from ancient Greece

Author: User “Bibi Saint-Poi”

Source: Wikimedia Commons

License: Public Domain

Finally, perhaps the most politically influential of the Pan-Hellenic cults was the oracle of Apollo at Delphi, established sometime in the eighth century BCE. Available for consultation only nine days a year, the oracle spoke responses to the questions asked by inquirers through a priestess, named the Pythia. The Pythia’s responses came in the form of poetry and were notoriously difficult to interpret. Nevertheless, city-states and major rulers throughout the Greek world considered it essential to consult the oracle before embarking on any major endeavor, such as war or founding a colony.

Maritime Trade and Colonization

The historian Herodotus records that sometime c. 630 BCE, the king of the small island of Thera traveled to Delphi to offer a sacrifice and consult the oracle on a few minor points. To his surprise, the oracle’s response had nothing to do with his queries. Instead, the Pythia directed him to found a colony in Libya, in North Africa. Having never heard of Libya, the king ignored the advice. A seven- year drought ensued, and the Therans felt compelled to consult the oracle again. Receiving the same response as before, they finally sent out a group of colonists who eventually founded the city of Cyrene.

While this story may sound absurd, it is similar to other foundation stories of Greek colonies and emphasizes the importance of the Delphic oracle. At the same time, though, this story still leaves open the question of motive: why did so many Greek city- states of the Archaic period send out colonies to other parts of the Greek world? Archaeology and foundation legends, such as those recorded by Herodotus, suggest two chief reasons: population pressures along with shortage of productive farmland in the cities on mainland Greece, and increased ease of trade that colonies abroad facilitated. In addition to resolving these two problems, however, the colonies also had the unforeseen impact of increasing interactions of the Greeks with the larger Mediterranean world and the ancient Near East. These interactions are visible, for instance, in the so-called Orientalizing style of art in the Archaic period, a style the Greeks borrowed from the Middle East and Egypt.

The presence of Greek colonies in Asia Minor also played a major role in bringing about the Greco-Persian Wars.

Figure 5.12 | Archaic kouros (youth) statue, c. 530 BC | Note the Egyptian hairstyle and body pose.

Author: User “Mountain”

Source: Wikimedia Commons

License: Public Domain

Aristocracy, Democracy, and Tyranny in Archaic Greece

Later Greek historians, including Herodotus and Thucydides, noted a certain trend in the trajectory of the history of most Greek poleis: most city-states started out with a monarchical or quasi- monarchical government. Over time the people gained greater representation, and an assembly of all citizens had at least some degree of political power—although some degree of strife typically materialized between the aristocrats and the poorer elements. Taking advantage of such civic conflicts, tyrants came to power in most city-states for a brief period before the people banded together and drove them out, thenceforth replacing them with a more popular form of government. Many modern historians are skeptical about some of the stories that the Greek historians tell about origins of some poleis; for instance, it is questionable whether the earliest Thebans truly were born from dragon teeth. Similarly, the stories about some of the Archaic tyrants seem to belong more to the realm of legend than history. Nevertheless, the preservation of stories about tyrants in early oral tradition suggests that city-states likely went through periods of turmoil and change in their form of government before developing a more stable constitution. Furthermore, this line of development accurately describes the early history of Athens, the best-documented polis.

In the early Archaic period, Athens largely had an aristocratic constitution. Widespread debt- slavery, however, caused significant civic strife in the city and led to the appointment of Solon as lawgiver for the year 594/3 BCE, specifically for the purpose of reforming the laws. Solon created a more democratic constitution and also left poetry documenting justifications for his reforms—and different citizens’ reactions to them. Most controversial of all, Solon instituted a one-time debt- forgiveness, seisachtheia, which literally means “shaking off.” He proceeded to divide all citizens into five classes based on income, assigning a level of political participation and responsibility commensurate with each class. Shortly after Solon’s reforms, a tyrant, Peisistratus, illegally seized control of Athens and remained in power off and on from 561 to 527 BCE. Peisistratus seems to have been a reasonably popular ruler who had the support of a significant portion of the Athenian population. His two sons, Hippias and Hipparchus, however, appear to have been less well-liked. Two men, Harmodius and Aristogeiton, assassinated Hipparchus in 514 BCE; then in 508 BCE, the Athenians, with the help of a Spartan army, permanently drove out Hippias. In subsequent Athenian history, Harmodius and Aristogeiton were considered heroes of the democracy and celebrated as tyrannicides.

Figure 5.13 | The structure of the Classical Athenian democracy, fourth century BCE

Author: User “Mathieugp”

Source: Wikimedia Commons

License: CC BY-SA 3.0

Immediately following the expulsion of Hippias, Athens underwent a second round of democratic reforms, led by Cleisthenes. The Cleisthenic constitution remained in effect, with few changes, until the Macedonian conquest of Athens in the fourth century BCE and is considered to be the Classical Athenian democracy. Central to the democracy was the participation of all citizens in two types of institutions: the ekklesia, an assembly of all citizens, which functioned as the chief deliberative body of the city; and the law-courts, to which citizens were assigned by lot as jurors. Two chief offices, the generals and the archons, ruled over the city and were appointed for one-year terms. Ten generals were elected annually by the ekklesia for the purpose of leading the Athenian military forces. Finally, the leading political office each year, the nine archons, were appointed by lot from all eligible citizens. While this notion of appointing the top political leaders by lot may seem surprising, it exemplifies the Athenians’ pride in their democracy and their desire to believe that, in theory at least, all Athenian citizens were equally valuable and capable of leading their city-state.

Developing in a very different manner from Athens, Sparta was seen by other Greek poleis as a very different sort of city from the rest. Ruled from an early period by two kings – one from each of the two royal houses that ruled jointly – Sparta was a true oligarchy, in which the power rested in its gerousia, a council of thirty elders, whose number included the two kings. While an assembly of all citizens existed as well, its powers were much more limited than were those of the Athenian assembly. Yet because of much more restrictive citizenship rules, Spartan assembly of citizens would have felt as a more selective body, as Figure 5.14 illustrates.

4.14 Structure of the Spartan Constitution

Author: User “Putinovac”

Source: Wikimedia Commons

License: CC BY 3.0

A crucial moment in Spartan history was the city’s conquest of the nearby region of Messenia in the eighth century BCE. The Spartans annexed the Messenian territory to their own and enslaved the inhabitants, called helots. While the helots could not be bought or sold, they were permanently tied to the land and could be punished or killed by any Spartan citizen. Compared to other Greek polei, Sparta’s population was overwhelmingly made up of these communally owned slaves, comprising at least 80% of the population, compared with about 40% in Athens. The availability of helot slave labor allowed the aristocratic elite from that point on to focus their attention on military training. These elite male Spartiates were raised in sex-segregated barracks from the age of 6 and subjected to harsh violence and competition. This focus transformed Sparta into the ultimate military state in the Greek world, widely respected by the other Greek poleis for its military prowess.

4.15 Map of Sparta and the Environs

Author: User “Marsyas”

Source: Wikimedia Commons

License: CC BY-SA 3.0

But while Athens and Sparta sound like each other’s diametrical opposites, the practices of both poleis ultimately derived from the same belief that all city-states held: that, in order to ensure their city’s survival, the citizens must place their city-state’s interests above their own. A democracy simply approached this goal with a different view of the qualifications of its citizens than did an oligarchy.

A final note on gender is necessary, in connection with Greek city-states’ definitions of citizenship. Only children of legally married and freeborn citizen parents could be citizens in most city-states. Women had an ambiguous status in the Greek poleis. While not full-fledged citizens themselves, they produced citizens. This view of the primary importance of wives in the city as the mothers of citizens resulted in diametrically opposite laws in Athens and Sparta, showing the different values that the respective cities emphasized. In Athens, if a husband caught his wife with an adulterer in his home, the law allowed the husband to kill said adulterer on the spot. The adultery law was so harsh precisely because adultery put into question the citizenship status of potential children, thereby depriving the city of future citizens. By contrast, Spartan law allowed an unmarried man who wanted offspring to sleep with the wife of another man, with the latter’s consent, specifically for the purpose of producing children. This law reflects the importance that Sparta placed on producing strong future soldiers as well as the communal attitude of the city towards family and citizenship.

The Persian Wars

Despite casting their net far and wide in founding colonies, the Greeks seem to have remained in a state of relatively peaceful coexistence with the rest of their Mediterranean neighbors until the sixth century BCE. In the mid-sixth century BCE, Cyrus, an able and energetic king of Persia mentioned in the previous chapter, expanded his rule with a sequence of victorious wars, ultimately consolidating under his rule the largest empire of the ancient world and earning for himself the title “Cyrus the Great.”

Cyrus’ Achaemenid Empire bordered the area of Asia Minor that had been previously colonized by the Greeks. This expansion of the Persian Empire brought the Persians into direct conflict with the Greeks and became the origin of the Greco-Persian Wars, the greatest military conflict the Greek world had known up until that point.

Over the second half of the sixth century, the Persians had taken over the western coast of Anatolia, known to the Greeks as Ionia, installing as rulers of these Greek city-states tyrants loyal to Persia. In 499 BCE, however, the Greek city-states in Asia Minor joined forces to rebel against the Persian rule. Athens and Eretria sent military support for this Ionian Revolt, and the rebelling forces marched on the Persian regional capital of Sardis and burned it in 498 BCE, before the revolt was finally subdued by the Persians in 493 BCE.

Seeking revenge on Athens and Eretria, the Persian king Darius launched an expedition in 490 BCE.

Darius’ forces captured Eretria in mid-summer, destroyed the city, and enslaved its inhabitants. Sailing a short distance across the bay, the Persian army then landed at Marathon. The worried Athenians sent a plea for help to Sparta. The Spartans, in the middle of a religious festival, refused to help. So, on September 12, 490 BCE, the Athenians, with only a small force of Plataeans helping, faced the much larger Persian army in the Battle of Marathon. The decisive Athenian victory showed the superiority of the Greek hoplite phalanx and marked the end of the first Persian invasion of Greece. Furthermore, the victory at Marathon, which remained a point of pride for the Athenians for centuries after, demonstrated to the rest of the Greeks that Sparta was not the only great military power in Greece.

Map 5.6 | The Achaemenid Empire under the rule of Cyrus

Author: User “Gabagool”

Source: Wikimedia Commons

License: CC BY 3.0

Darius died in 486 BCE, having never realized his dream of revenge against the Greeks. His son, Xerxes, however, continued his father’s plans and launched in 480 BCE a second invasion of Greece, with an army so large that, as the historian Herodotus claims, it drank entire rivers dry on its march. The Greek world reacted in a much more organized fashion to this second invasion than it did to the first. Led by Athens and Sparta, some seventy Greek poleis formed a sworn alliance to fight together against the Persians. This alliance, the first of its kind, proved to be the key to defeating the Persians as it allowed the allies to split forces strategically in order to guard against Persian attack by both land and sea. The few Greek city-states who declared loyalty to the Persian Empire instead–most notably, Thebes–were seen as traitors for centuries to come by the rest of the Greeks.

Map 5.7 | Map of the Greek World during the Persian Wars (500-479 BCE)

Author: User “Bibib Saint-poi”

Source: Wikimedia Commons

License: CC BY-SA 3.0

Marching through mainland Greece from the north, the Persians first confronted the Spartans at the Battle of Thermopylae, a narrow mountain pass that stood in the way of the Persians’ accessing any point south. In this now-legendary battle the Greek army successfully defended the pass for two days before being betrayed by a local who showed a roundabout route to the Persians. The Persians then were able to outflank Greeks, but the 300 Spartans from the Greek force and their king Leonidas refused to retreat. They held out in the pass until they were surrounded and killed to the last man. This battle, although a loss for the Greeks, bought crucial time for the rest of the Greek forces in preparing to face the Persians. The 300 choosing death over defeat also became a key part of the Spartan mythos as the greatest warriors and a famous example of duty and bravery.

The victory at Thermopylae fulfilled the old dream of Darius, as it allowed access to Athens for the Persians. The Athenian statesman Themistocles, however, had ordered a full evacuation of the city in advance of the Persian attack through an unusual interpretation of a Delphic oracle stating that wooden walls will save Athens. Taking the oracle to mean that the wooden walls in question were ships, Themistocles used the Athenian fleet which to send all of the city’s inhabitants to safety. His gamble proved to be successful, and the Persians captured and burned a mostly empty city.

The Athenians proceeded to defeat the Persian fleet at the Battle of Salamis, off the coast of Athens, turning the tide of the war in favor of the Greeks as Xerxes’ huge army could not feed itself without shipping in food. Finally, in June of 479 BCE, the Greek forces were able to strike the two final blows, defeating the Persian land and sea forces on the same day in the Battle of Plataea on land and the Battle of Mycale on sea. The victory at Mycale also resulted in a second Ionian revolt, which this time ended in a victory for the Greek city-states in Asia Minor. Xerxes was left to sail home to his diminished empire.

It is difficult to overestimate the impact of the Persian Wars on subsequent Greek history. Seen by historians as the end-point of the Archaic Period, the Persian Wars cemented Pan-Hellenic identity, as they saw cooperation on an unprecedented scale among the Greek city-states. In addition, the Persian Wars showed the Greek military superiority over the Persians on both land and sea. Finally, the wars showed Athens in a new light to the rest of the Greeks. As the winners of Marathon in the first invasion and the leaders of the navy during the second invasion, the Athenians emerged from the wars as the rivals of Sparta for military prestige among the Greeks. This last point, in particular, proved to be the most influential for Greek history in the subsequent period.

THE CLASSICAL PERIOD

So far, the story of the Greek world in this chapter has proceeded from a narrative of the fragmented Greek world in the Dark Ages to the emergence and solidification of a Pan-Hellenic identity in the Archaic Period. The story of the Greeks in the Classical Period, by contrast, is best described as the strife for leadership of the Greek world. First, Athens and Sparta spent much of the fifth century BCE battling each other for control of the Greek world. Then, once both were weakened, other states began attempting to fill the power vacuum. Ultimately, the Classical Period will end with the Greek world under the control of a power that was virtually unknown to the Greeks at the beginning of the fifth century BCE: Macedon.

From the Delian League to the Athenian Empire

In 478 BCE, barely a year after the end of the Persian Wars, a group of Greek city-states, mainly those located in Ionia and on the island between mainland Greece and Ionia, founded the Delian League, with the aim of continuing to protect the Greeks in Ionia from Persian attacks. Led by Athens, the league first met on the tiny island of Delos. According to Greek mythology, the twin gods Apollo and Artemis were born on Delos. As a result, the island was considered sacred ground and, as such, was a fitting neutral headquarters for the new alliance. The league allowed member states the option of either contributing a tax (an option that most members selected) or contributing ships for the league’s navy. The treasury of the league, where the taxes paid by members were deposited, was housed on Delos.

Over the next twenty years, the Delian League gradually transformed from a loose alliance of states led by Athens to a more formal entity. The League’s Athenian leadership, in the meanwhile, grew to be that of an imperial leader. The few members who tried to secede from the League, such as the island of Naxos, quickly learned that doing so was not an option as the revolt was violently subdued. Finally, in 454 BCE, the treasury of the Delian League moved to Athens. That moment marked the transformation of the Delian League into the Athenian Empire.

Since the Athenians publicly inscribed each year the one-sixtieth portion of the tribute that they dedicated to Athena, records survive listing the contributing members for a number of years, thereby allowing historians to see the magnitude of the Athenian operation.

While only the Athenian side of the story survives, it appears that the Athenians’ allies in the Delian League were not happy with the transformation of the alliance into a full-fledged Athenian Empire. Non-allies were affected a well. The fifth-century BCE Athenian historian Thucydides dramatizes in his history one particularly harsh treatment of a small island, Melos, which effectively refused to join the Athenian cause. To add insult to injury, once the treasury of the Empire had been moved to Athens, the Athenians had used some funds from it for their own building projects, the most famous of these projects being the Parthenon, the great temple to Athena on the Acropolis.

The bold decision to move the treasury of the Delian League to Athens was the brainchild of the leading Athenian statesman of the fifth century BCE, Pericles. A member of a prominent aristocratic family, Pericles was a predominant politician for forty years, from the early 460s BCE to his death in 429 BCE, and was instrumental in the development of a more popular democracy in Athens. Under his leadership, an especially vibrant feeling of Athenian patriotic pride seems to have developed, and the decision to move the Delian League treasury to Athens fits into this pattern as well. Shortly after moving the treasury to Athens, Pericles sponsored a Citizenship Decree in 451 BCE that restricted Athenian citizenship from thence onwards only to individuals who had two freeborn, married Athenian parents, both of whom were also born of Athenian parents. Then c. 449 BCE, Pericles successfully proposed a decree allowing the Athenians to use Delian League funds for Athenian building projects, and, c. 447 BCE, he sponsored the Athenian Coinage Decree, a decree that imposed Athenian standards of weights and measures on all states that were members of the Delian League. Later in his life, Pericles famously described Athens as “the school of Hellas;” this description would certainly have fit Athens just as much in the mid-fifth century BCE as, in addition to the flourishing of art and architecture, the city was a center of philosophy and drama.

Figure 5.15 | Model of the Acropolis, with the Parthenon in the middle

Author: User “Benson Kua”

Source: Wikimedia Commons

License: CC BY-SA 2.0

The growing wealth and power of Athens in the twenty or so years since the Persian Wars did not escape Sparta and led to increasingly tense relations between the two leading powers in Greece. Sparta had steadily consolidated the Peloponnesian League in this same time-period, but Sparta’s authority over this league was not quite as strict as was the Athenian control over the Delian League. Finally, in the period of 460-445 BCE, the Spartans and the Athenians engaged in a series of battles, to which modern scholars refer as the First Peloponnesian War. In 445 BCE, the two sides swore to a Thirty Years Peace, a treaty that allowed both sides to return to their pre-war holdings, with few exceptions. Still, Spartan unease in this period of Athenian expansion and prosperity, which resulted in the First Peloponnesian War, was merely a sign of much more serious conflict to come. As the Athenian general and historian Thucydides later wrote about the reasons for the Great Peloponnesian War, which erupted in 431 BCE: “But the real cause of the war was one that was formally kept out of sight. The growing power of Athens, and the fear that it inspired in Sparta, made the war inevitable” (Thucydides, I.23).

The Peloponnesian War (431 – 404 BCE)

Historians today frown on the use of the term “inevitable” to describe historical events. Still, Thucydides’ point about the inevitability of the Peloponnesian War is perhaps appropriate, as following a conflict that had been bubbling under the surface for fifty years, the war finally broke out over a seemingly minor affair. In 433 BCE, Corcyra, a colony of Corinth that no longer wanted to be under the control of its mother-city, asked Athens for protection against Corinth. The Corinthians claimed that the Athenian support of Corcyra was a violation of the Thirty Years Peace. At a subsequent meeting of the Peloponnesian League in Sparta in 432 BCE, the allies, along with Sparta, voted that the peace had been broken and so declared war against Athens.

At the time of the war’s declaration, no one thought that it would last twenty-seven years and would ultimately embroil the entire Greek-speaking world. Rather, the Spartans expected that they would march with an army to Athens, fight a decisive battle, then return home forthwith. The long duration of the war, however, was partly the result of the different strengths of the two leading powers. Athens was a naval empire, with allies scattered all over the Ionian Sea. Sparta, on the other hand, was a land-locked power with supporters chiefly in the Peloponnese and with no navy to speak of at the outset of the war.

The Peloponnesian War brought about significant changes in the government of both Athens and Sparta, so that, by the end of the war, neither power looked as it did at its outset. Athens, in particular, became more democratic because of increased need for manpower to row its fleet. The lowest census bracket, the thetes, whose poverty and inability to buy their own armor had previously excluded them from military service, became by the end of the war a full-fledged part of the Athenian forces and required a correspondingly greater degree of political influence. In the case of Sparta, the war had ended the Spartan policy of relative isolationism from the rest of the affairs of the Greek city-states. The length of the war also brought about significant changes to the nature of Greek warfare. While war was previously largely a seasonal affair, with many conflicts being decided with a single battle, the Peloponnesian War forced the Greek city-states to support standing armies. Finally, while sieges of cities and attacks on civilians were previously frowned upon, they became the norm by the end of the Peloponnesian War.

Map 5.9 | Map of the Peloponnesian War Alliances at the Start and Contrasting Strategies, 431 BCE

Author: User “Magnus Manske”

Source: Wikimedia Commons

License: Public Domain

The long war was punctuated by many reversals of fortune and one long truce. In the end, three main factors led to Athenian defeat: Athens overconfidently attacked the neutral state of Syracuse, a strategic blunder and tactical catastrophe driven by the personal ambitions of various notable Athenians; Athens twice failed to defeat Sparta on land in major battles; and Sparta eventually accepted money from Persia to build itself a fleet, which after several failures defeated Athens and forced its surrender. Sparta disbanded the Athenian empire and installed a pro-Spartan Oligarchy, the ‘Thirty Tyrants”, who lasted little more than a year before being overthrown.

5.10.3 Athenian Culture during the Peloponnesian War

Because it drained Athens of manpower and financial resources, the Peloponnesian War proved to be an utter practical disaster for Athens. Nevertheless, the war period was also the pinnacle of Athenian culture, most notably its tragedy, comedy, and philosophy. Tragedy and comedy in Athens were very much popular entertainment, intended to appeal to all citizens. Thus issues considered in these plays were often ones of paramount concern for the city at the time when the plays were written. As one character in a comedy bitterly joked in an address to the audience, more Athenians attended tragic and comic performances than came to vote at assembly meetings. Not surprisingly, war was a common topic of discussion in the plays. Furthermore, war was not portrayed positively, as the playwrights repeatedly emphasized the costs of war for both winners and losers.

Sophocles, one of the two most prominent Athenian tragedians during the Peloponnesian War era, had served his city as a general, albeit at an earlier period; thus, he had direct experience with war. Many of his tragedies that were performed during the war dealt with the darker side of fighting, for both soldiers and generals, and the cities that are affected. By tradition, however, tragedies tackled contemporary issues through integrating them into mythical stories, and the two mythical wars that Sophocles portrayed in his tragedies were the Trojan War, as in Ajax and Philoctetes, and the aftermath of the war of the Seven against Thebes, in which Polynices, the son of Oedipus, led six other heroes to attack Thebes, a city led by his brother Eteocles, as in Oedipus at Colonus. Sophocles’ plays repeatedly showed the emotional and psychological challenges of war for soldiers and civilians alike; they also emphasized the futility of war, as the heroes of his plays, just as in the original myths on which they were based, died tragic, untimely deaths. Sophocles’ younger contemporary, Euripides, had a similar interest in depicting the horrors of war and wrote a number of tragedies on the impact of war on the defeated, such as in Phoenician Women and Hecuba; both of these plays explored the aftermath of the Trojan War from the perspective of the defeated Trojans.

While the tragic playwrights explored the impact of the war on both the fighters and the civilians through narrating mythical events, the comic playwright Aristophanes was far less subtle. The anti-war civilian who saves the day and ends the war was a common hero in the Aristophanic comedies. For instance, in the Acharnians (425 BCE), the main character is a war-weary farmer who, frustrated with the inefficiency of the Athenian leadership in ending the war, brokers his own personal peace with Sparta. Similarly, in Peace (421 BCE), another anti-war farmer fattens up a dung beetle in order to fly to Olympus and beg Zeus to free Peace. Finally, in Lysistrata (411 BCE), the wives of all Greek city-states, missing their husbands who are at war, band together in a plot to end the war by going on a sex-strike until their husbands make peace. By the end of the play, their wish comes true. Undeniably funny, the jokes in these comedies, nevertheless, have a bitter edge, akin to the portrayal of war in the tragedies. The overall impression from the war-era drama is that the playwrights, as well as perhaps the Athenians themselves, spent much of the Peloponnesian War dreaming of peace.

While the legacy of Athenian drama and art was deeply influential, its most lasting legacy was one that Athenians living at the time likely would never have guessed: the writings of a few men who called themselves ‘philosophers’, or lovers of wisdom. Seen by many Athenians as foolish fancies aptly deserving mockery (as indeed philosophy was mocked in Aristophanes’ play Clouds), the philosophical writings of Plato and other Greeks can be seen as the starting point of the Western intellectual heritage. It is to this topic that we now turn in the next chapter.

This chapter contains material from

World History: Cultures, States and Societies to 1500 by Berger et. al. and is used under a CC BY-SA 4.0 license.

World History to 1700 by Rene L. M. Paredes and is used under a CC BY 4.0 license.

Media Attributions

4.1 The Cup of Nestor by Marcus Cyron, in the public domain

4.2 The Inscription by Future Perfect at Sunrise, in the public domain

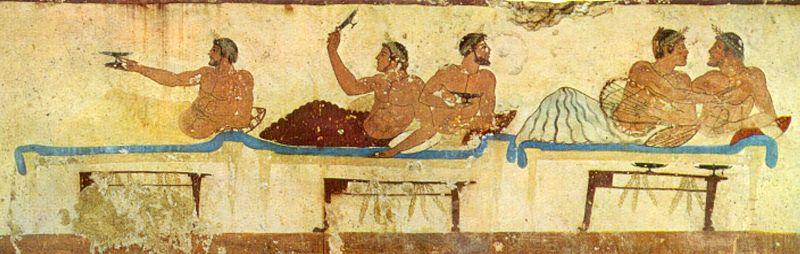

4.3 Depiction of a Symposium by Amandajm, in the public domain

4.4 Map of Greek Archaic Settlement by Dipa1965 is licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0

4.5 Minoan Crete by Bibi Saint-Pol is licensed under CC BY-SA 3.0

4.6 The Bull Leaping Fresco by Jebulon, in the public domain

Feedback/Errata