3 Egypt and the Cycle of Empire

Rise

Founder of Egypt

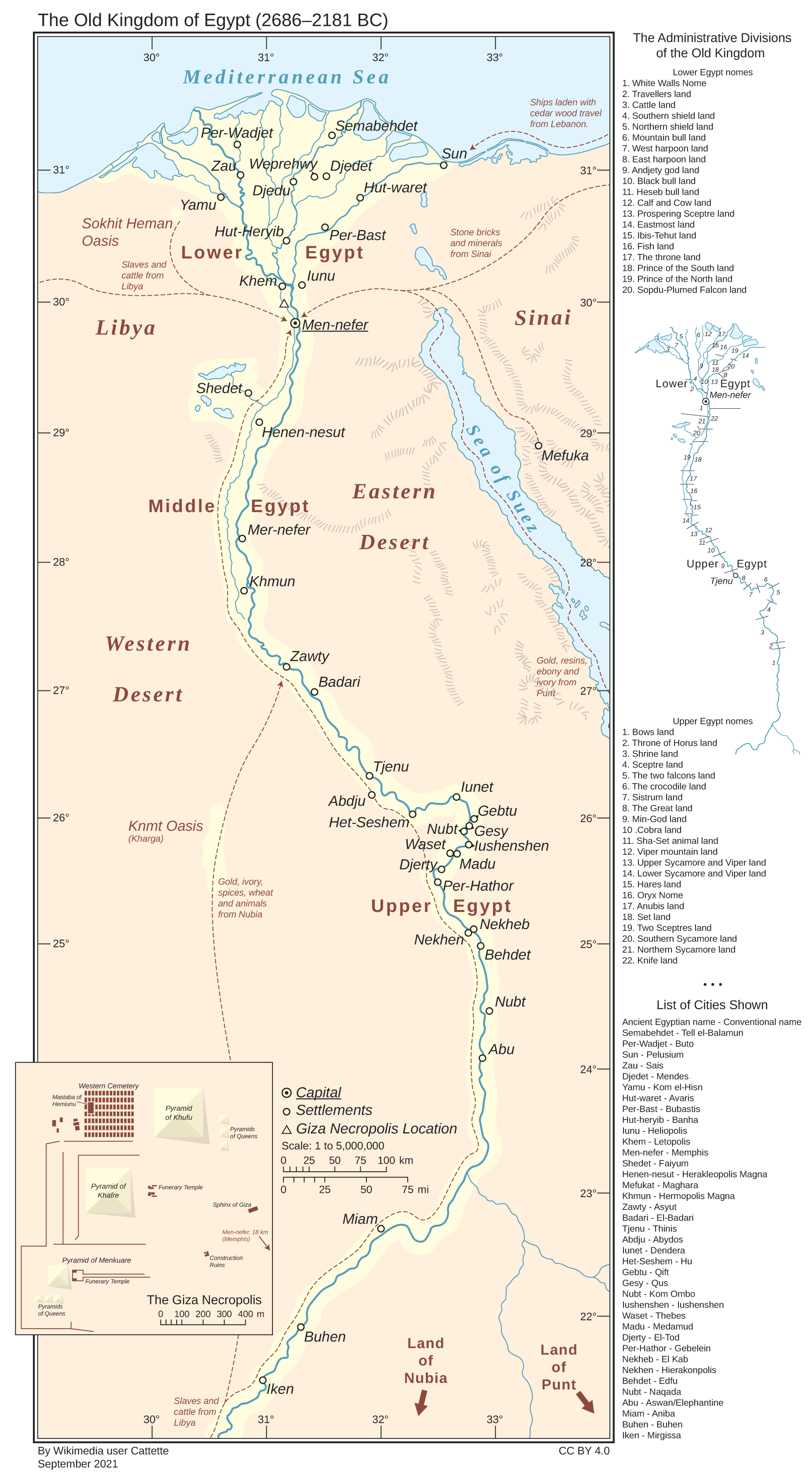

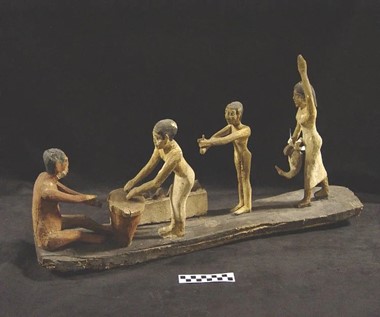

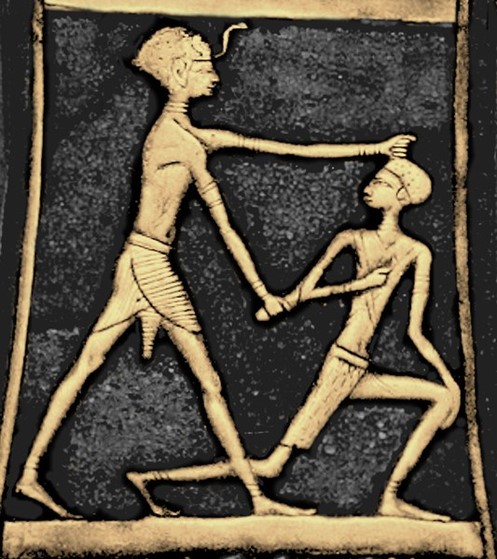

Sargon of Akkad was not the first emperor: that honour (if honour it is) goes to an Egyptian king who united the two halves of Egypt into a single state. This achievement was reflected in the crown that thereafter served as the symbol of Egyptian rulership: the ‘double crown’, which included the tall white crown of upper (southern) Egypt and the swept-back red crown of lower (northern) Egypt. The conquest may have been by a king called Narmer. He is represented as a conqueror who ruled over both halves of Egypt on the exquisitely carved ‘Narmer’s palette’, one of the most significant archaeological objects ever found, alongside the Rosetta stone and Hammurabi’s stele. The tablet may show symbols of the cities he conquered, and the apparently decapitated corpses indicate the violence that accompanied the beginnings of united Egypt.

The unification of Egypt was one of the most successful and long-lived of imperial conquests, as the land was geographically a natural unit. From the first cataract in the south at Aswan down to where the delta eases into the sea, the smooth, slow current of the Nile forms a mighty and permanent highway that connected every Egyptian city. Packed into the rich farmland of the Nile’s floodplain between the inhospitable ‘red land’ of the desert to either side, the Egyptians shared a language and syncretized the gods of their various cities to form a unified pantheon. While Egyptian power sometimes conquered lands beyond, the waters of the Nile created an identity that transformed Egypt from empire to nation.

The Nile is the world’s longest river, stretching over 4,000 miles from its mouth in the Mediterranean to its origin in Lake Victoria in Central Africa. Because of consistent weather patterns, the Nile floods every year at just about the same time (late summer), depositing enormous amounts of mud and silt along its banks and making it one of the most fertile regions in the world. The essential source of energy for the Egyptians was thus something that could be predicted and planned for in a way that was impossible in Mesopotamia.

The Egyptians themselves called the Nile valley “Kemet,” the Black Land, because of the annually-renewed black soil that arrived with the flood: a swath of land between 10 and 20 miles wide (and in some places merely 1 or 2 miles wide) made up of the incredibly fertile soil. This created an enormous surplus of wealth for the royal government, which had the right to tax and redistribute it (as did the Mesopotamian states to the east). Beyond that strip of land were deserts populated by people the Egyptians simply dismissed as “bandits” – meaning pastoral nomads and tribal groups, not just robbers.

Conquest

Narmer’s unification of Egypt under a line of kings was the first such imperial foundation we know of in history, but it was far from the last. Imperial conquests and kingly dynasties pop up with increasing frequency wherever agriculture spreads. While kingly empires are the most common kind in premodern times, there are other types of imperial government as well, including republican, democratic, and oligarchic systems. While these differences are important in their way, just as important are other cultural differences — of law, of gender roles, of social stratification — that affected people within the empire and distinguished daily life in one empire from another. Conversely, there are many similarities that empires tend to share precisely because they are empires. We will examine these similarities throughout this chapter using Egypt as our main example.

Almost every empire comes into being via conquest or the threat of conquest. In cases such as Narmer or Sargon, the conquest is by a king using the resources of the state he leads to subjugate his neighbours. The conquering group can also be a stateless society, such as a tribal confederation, which takes advantage of favourable circumstances to invade and subjugate either similarly stateless neighbours, or a settled civilization that for whatever reason has become vulnerable.

The instrument of imperial conquest is the campaigning army. In some cases, such as the Macedonian empires of Alexander and his successors, or the nomad-ruled empires of the Huns or Mongols, the campaigning army had a nearly permanent existence and formed the core of the imperial state; in others it was created as needed using pre-existing imperial authority. Armies are enormously large and complex entities that take different forms in different cultures, but they share certain similarities, particularly those which are able to consistently fight and win battles in foreign territory. The main problem is how to bring together, organize and feed thousands (or tens or hundreds of thousands) of soldiers while they march and fight in hostile territory.

Mobilizing requires institutions to summon together huge numbers of people in a prompt and effective way. This is much easier if the people are eager to go on campaign, which can be the case if the culture celebrates warfare and and a history of successful conquest, and/or if the enemy is hated by the population based on past hostilities. But it is generally much harder to motivate soldiers to attack others than to defend against an attack. Even if the population is willing, the soldiers still must be identified, notified, gathered and organized, which given the vast quantities of people involved will not be a simple task.

Empires recruit their soldiers in a variety of different ways. Militia were mentioned in the previous chapter. For aggressive campaigns that take soldiers into enemy territory, a militia made up of the entire male population is less practical, and often communities will be asked to furnish some number of men each time a campaign is announced. Generally the community will also provide them with food and military gear, including weapons. A more formal arrangement can designate certain men or families as having military responsibilities, sometimes in return for land or special privileges. If these responsibilities are hereditary and tied in to land-ownership and high social status, the system is often called ‘feudalism’, where an aristocratic, military land-owning class plays a central role in the society.

An alternative, more centralised structure involves a standing army or the use of mercenaries or conscripts. What these all have in common is a body of full-time soldiers paid a salary by the state. ‘Conscripts’ generally indicates a less permanent organisation, such as when troops are levied periodically for wars and might return to civilian life after the war is over, whereas a professional army usually indicates long service including in peacetime. Mercenaries are distinguished from either of these by owing no special loyalty to the state that they fight for other than their pay; often they are foreign, organised into some kind of autonomous military company that has taken on short or long-term service in return for wages and perhaps the prospect of loot.

Once the campaigning army is gathered and marched into enemy territory it must be fed. Feeding huge numbers of people for weeks or months is a huge planning challenge, and failing in it leads to starvation and disaster. It can partly be done by plundering the invaded lands, but even this requires substantial organization, to ensure that the army can function and defend itself while scouring the area for food and is operating in a time and place where enough food is available to be taken. But campaigning armies generally must organize complex networks of ship transports and wagons to provide themselves with reliable supplies. The larger the scope of the imperial conquests, the further the campaigning army must venture from its home territory, and the harder it is to arrange the delicate transport system needed to keep the army alive.

A campaigning army is like a city on the move, often larger than all but the hugest contemporary cities. Aside from the soldiers, many other people are usually part of the army — particularly labourers working to transport the food and equipment, but also ‘camp-followers’ of many kinds — merchants, doctors, cooks, entertainers, sex workers, messengers, bureaucrats, craftsmen and engineers. Armies generally campaigned for only part of the year, but that still meant spending months marching, camping in the field, living outdoors. Wherever they went they left a huge impact. Like a locust swarm, they ate everything in their path, often leaving famine behind. In territory they saw as hostile, they spread unimaginable suffering and destruction. A swath of burned villages and devastated lands filled with murder, rape and enslavement were the normal accompaniments of campaigning armies, and farmers and other civilians learned to flee for the safety of woods and mountains at the approach of troops. Those peasants who avoided the hostile soldiers might still starve to death months later, with their seed grain stolen and their animals butchered and eaten. Even ‘friendly’ armies were likely to take food and property at will, and undisciplined soldiers were an unpredictable danger to everyone in their vicinity, notoriously prone to theft, vandalism, and sexual assault.

Conquest of civilized lands required the ability to capture fortified cities, which is enormously difficult. The two main ways of capturing a resisting fortified city is by siege or assault. Sieges require an army large enough to surround the city, cutting off any ability of the city to draw in food from the countryside. For port cities, this also requires coordinating with a fleet to blockade the city from the sea, a difficult and complex task in itself. While the siege goes on, the besieging army must be able to feed itself by plundering the countryside and transporting food from afar, a task made enormously easier with access to sea or river transport. Maintaining control and motivation in an army for months or years under difficult conditions in order to starve a city into submission is an administrative and organizational challenge that can be failed in myriad ways.

Assaulting a city requires technological and organizational expertise, to allow the attacking army to break through, destroy or surmount the city’s fortifications with enough troops to overcome (usually) large numbers of (usually) very motivated defenders. Solutions included tunnelling under and collapsing walls, battering rams to break gates and walls, missile engines such as catapults, concentrated arrow fire to kill or push away defenders, and ladders, ramps or towers to gain access to the walls. Such skills and techniques were difficult to develop, and we generally find them used by successful, expansionist empires. Some of the earliest evidence for many of these techniques is in the surviving art of the Assyrian empire, a Mesopotamian kingdom that first began subjugating its neighbours in the second millennium BC.

When cities were captured by a campaigning army, they were often sacked, which ranged from a relatively orderly stealing of valuables up to the total destruction of the city and the massacre or enslavement of its whole population. In order to encourage cities to surrender rather than resist, many expansionist empires developed a policy of destroying cities that defended themselves, while offering gentler treatment to cities that surrendered immediately. This could involve detailed negotiations around the terms of surrender, including the tribute or taxes that would be paid by the surrendering city, supplies or shelter it might offer to the army, and what government institutions it might retain. As time passed many of the most prosperous cities in Eurasia changed overlords repeatedly, weathering the rise and fall of empires via careful diplomacy and strategic surrender. Catastrophe was never far, however, depending on the decisions and whims of mighty generals with few checks on their power when they marched at the head of an army on campaign.

A campaigning army could fail for many reasons. It could be defeated by a defending army in a battle; it could starve on campaign; it could fail to capture the key cities or fortifications that it needed to. One of the most common causes of a failed campaign was the spread of disease in the campaigning armies. Armies generally were one of the best environments imaginable for bacteria and viruses to spread: dense gatherings of people living in poor conditions, often malnourished and travelling from place to place. In more modern times where we have reliable numbers, disease always killed many more soldiers in campaigning armies than battles did. This surely was also the case in ancient times, and we have some dramatic stories of armies being destroyed or sieges broken by the spread of disease. Disease could be especially demoralizing since its natural causes were not understood and it could be easily interpreted as a curse from the gods, as it is represented in the Greek epic poem The Iliad when it threatens the Greek siege of Troy. Similarly, the survival of Jerusalem when Sennecharib campaigned against it is represented in the Tanakh as a divine intervention that struck down the Assyrians, and could have been connected to a plague in the campaigning army.

From the Iliad, chapter 1, Apollo spreads plague:

He came down from Olympus top enraged,

carrying on his shoulders bow and covered quiver,

his arrows rattling in anger against his arm.

He sat some distance from the ships, shot off an arrow—

the silver bow reverberating ominously.

First, the god massacred mules and swift-running dogs,

then loosed sharp arrows in among the troops themselves.

Thick fires burned the corpses ceaselessly.

If the campaigning army overcame and conquered its foes, the subjugated population could face many different outcomes. At the worse end, they might be massacred or driven off their land. One tactic employed by some empires, for example the Assyrians, was relocating subjugated populations into new places, which made them easier to control. Sometimes these fates were reserved for aristocrats and elites, with the peasants left alone. Some amount of enslavement was very common. Often, new leaders would be installed, either foreign governors from the conquering culture, or local elites chosen to act as puppets. When Egypt controlled the eastern coast of the Mediterranean, it usually governed by installing subservient local rulers supported by small garrisons of Egyptian soldiers. Sometimes ‘colonies’ were founded, meaning here groups of settlers from the conquering culture that were given land to live inside the subjugated territory, often forming a new town or city. This was sometimes used as a way to reward the soldiers of the victorious army, and it had the advantage of that the colonists could keep an eye on their subjugated neighbours and help maintain the imperial power, particularly if they were veteran, retired soldiers. Regardless of what other changes were imposed, every empire would implement its system of local wealth extraction, mobilizing taxes, workers or troops via its imperial institutions for the benefit of the imperial center (called the metropole). The extent of these impositions varied greatly, often limited by inefficient bureacratic institutions and the quiet resistance of local elites to be less heavy than the rulers would have preferred.

Rule

Culture

The process of creating an empire (as opposed to simply plundering or destroying neighbours) requires either creating or co-opting state institutions in order to keep control over the subjugated people. For both Sargon and Narmer, there were existing governments in the cities that they conquered that they could use as the basis for their local administrations. This form of empire was common, where central institutions of empire were minimal, and the empire contained the pre-existing states it had conquered as mostly autonomous units, whose main responsibility was to deliver taxes and labour to the metropole. Since city-states were generally the first and most basic kind of state unit, it was quite natural for empires to incorporate cities that had long histories and traditional institutions without substantially disrupting their internal affairs. The prospect of remaking the local society on a new pattern was an ambitious, difficult undertaking.

While empires often impacted their subjects mainly through taxes and forced labour, they also integrated the lands they ruled linguistically and culturally. Some empires tried to impose their religion, language, political structures, or other habits throughout the lands they ruled. And sometimes these institutions spread via imitation and transmission quite independently of any intention of the imperial rulers. The status and power of the dominant culture in an empire could inspire others to assimilate, gradually spreading a shared set of values and practices throughout the land. And, in the other direction, the rulers of an empire could assimilate to the culture of their subjects. This happened especially when a smaller, non-civilized group of conquerors took over an already established and somewhat homogenous empire — for example China, Rome or Persia, all of which were conquered at various points by uncivilized neighbours and whose cultures shaped their conquerors at least as much as they were themselves reshaped.

When a conquering group was ethnically different from the conquered population, an ethno-racial hierarchy could emerge, where the new aristocratic class of the empire was the conquering ethnicity. If the ruling group believed its ethnic identity to be hereditary, the boundaries of the aristocracy became racial — that is, based on ancestry that divided people into distinct and hierarchical hereditary groups. This may have happened in Sargon’s empire, with Akkadians taking on a dominant role over subjugated Sumerians, and some element of ethno-racial hierarchy was very common in pre-modern empires (and modern ones, for that matter). This could take the form of a ruling elite where only members of the dominant ethnicity formed the aristocracy, or a more informal situation where the dominant ethnicity partly shared and diffused its power.

State Religion

Regardless of the origins of an empire, if it lasted any length of time it combined coercive power with social legitimacy. This legitimacy was rooted partly in concrete benefits imperial rule gave to the population, and partly in popular acceptance of the rightfulness and desirability of imperial rule. A major component of this cultural legitimation was the development of a state religion, which in one way or another supported the existing rulers as having a divine mandate to govern. These state religions took pre-existing cults, gods and practices and recast them in ways to offer support for the state.

We can see an aspect of this at work in the religion of the first empire, Egypt, with its famous pantheon of gods: Horus, Ra, Osiris, Isis, Thoth, Maat, Hathor, Anubis, Set, Ptah, Amun, Re, Sekhmet, Nefertem, Bastet, and so on, through hundreds of deities. The vast majority of the gods of the Egyptian pantheon can be identified as having been local gods worshipped in particular cities. When the Egyptian cities were unified into the kingdom of Egypt, the local gods could come to greater prominence, spreading their worship along the Nile — especially those favored by the royal family or backed by powerful priesthoods and temple complexes, . The popularity of certain gods, as seen in depictions, inscriptions and invocations that have survived to the present day, grew and shrank over time. Any attempt to impose an overall order on the Egyptian pantheon — a project first attempted by the Egyptian priesthood themselves early in its history — was made problematic both by the profusion of gods, often with overlapping identities and domains, and by the way that the religion itself changed over the millennia of Egyptian history.

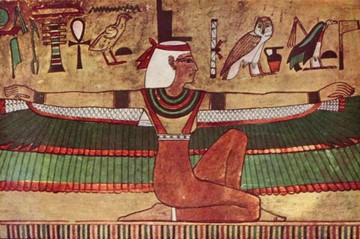

One early, important Egyptian myth was that of the death and resurrection of Osiris. Osiris, the god who ruled Egypt as king, is killed by his brother Set, but is resurrected by his wife Isis and impregnates her. She gives birth to their son, Horus, and hides him until he can avenge his father and depose Set from his stolen throne. Osiris then reigns in the underworld as lord of the dead and Horus takes his place as king of Egypt, returning righteous rule to the land. This mythological cycle became one of the most retold in Egypt, found in many versions in many places. One reason for this is the role it played in legitimating the Egyptian kingship. The ruling king was understood as the embodiment of Horus, his dead father as Osiris, and upon the king’s death he takes on a new position in the underworld even as his son rises to take his place.

The myth also draws a clear distinction between unrighteous rulership (seized by force, unjust to the people) and righteous kingship (passed on by heredity, rightly ordered, executing justice). The key concept is expressed in the ancient Egyptian word ma’at, sometimes personified as a goddess, the wife of Thoth, god of writing and knowledge. Ma’at was the righteous ordering of the world, uniting order, truth and justice into the correct, harmonious system of life. The concept presupposes a natural state of affairs that is divine, eternal and good, but which can be upset by incorrect action. In individual life, a person could live either according to ma’at by dealing honestly, kindly and benevolently with others or disrupt the right order of things by departing from ma’at. This was particularly important for the kings of Egypt, who as the ideology developed depicted themselves as the ‘lords of ma’at’, whose rule was the most important part of the divine order. As one 25th century BCE document puts it,

Ma’at is good and its worth is lasting.

It has not been disturbed since the day of its creator,

whereas he who transgresses its ordinances is punished.

It lies as a path in front even of him who knows nothing.

Wrongdoing has never yet brought its venture to port.

(Frankfort, Henri. Ancient Egyptian Religion. p. 62.)

The faithful adherence to ma’at was essential both for ordinary material prosperity and for spiritual health; both for the security of the social order and for the stability of nature. The annual flooding of the Nile, the steady winds that blew south from the Mediterranean, the natural cycle of growth in flocks and crops, all reflected the fundamentally good order in nature that ma’at represented; droughts, earthquakes, famines, and epidemics were deviations from this order and might be effects of failures in the human order of ma’at upheld by the king and his deputies. The order in the state and the order in nature were intimately connected.

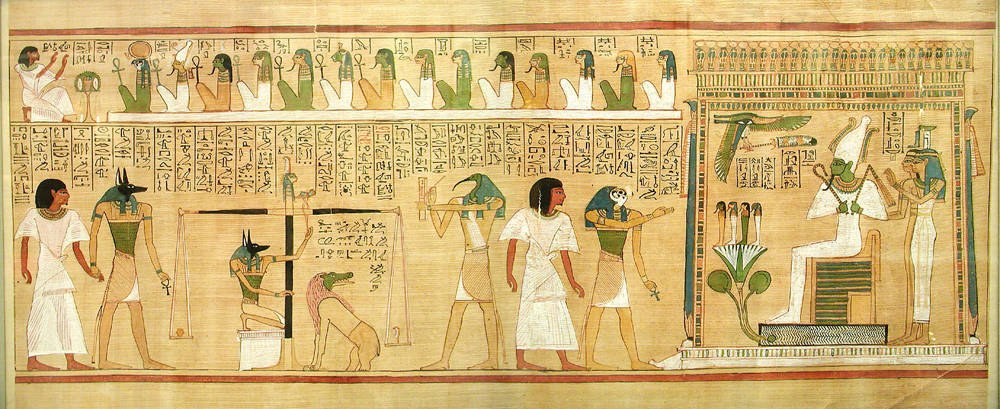

Ma’at also became essential to the Egyptian conception of the afterlife and immortality. Egyptians developed the idea that the soul would survive the death of the body and, passing through the underworld with the aid of magic spells past dangerous guardians, would face a test of its righteousness in life. The heart of the dead person would be weighed on a scale against a feather, representing ma’at; if it was burdened with misdeeds the heart would be consumed by the fearsome crocodile-headed goddess Ammit, condemning the deceased to a restless afterlife instead of blissful continuation in the company of the gods. Texts providing the spells needed to navigate the difficult journey were written on coffins and inside tombs. One of these spells lists the many various sins that would violate ma’at, including theft, murder, lying, lawbreaking, fornication, profiteering grain, disobeying the king, and cursing the gods.

By supporting the rightful place of the king at the head of the state, and connecting the social structure of Egypt with divinely ordained order, the Egyptian religion supported obedience to governing power alongside wide-ranging moral expectations. But the support that the Egyptian religion provided to the state went beyond values; the institutions of temples and priesthood were also essential parts of the government. Unlike in Sumer, Egyptian temples were not centers of the government bureacracy, but they still had an important role in Egyptian life.

Priests, like scribes, went through a prolonged training period before beginning service and, once ordained, took care of the temple or temple complex, performed rituals and observances (such as marriages, blessings on a home or project, funerals), acted as doctors, healers, astrologers, scientists, and psychologists, and also interpreted dreams. They blessed amulets to ward off demons or increase fertility, and also performed exorcisms and purification rites to rid a home of ghosts. Their chief duty was to the god they served and the people of the community, and an important part of that duty was their care of the temple and the statue of the god within.

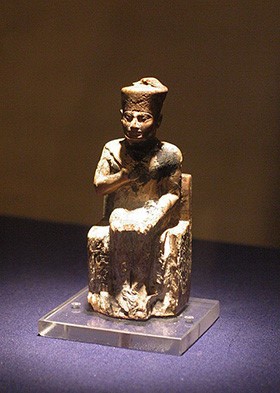

The temples of ancient Egypt were thought to be the literal homes of the deities they honored. Every morning the head priest or priestess, after purifying themselves with a bath and dressing in clean white linen and clean sandals, would enter the temple and attend to the statue of the god as they would to a person they were charged to care for. The doors of the sanctuary were opened to let in the morning light, and the statue, which always resided in the innermost sanctuary, was cleaned, dressed, and anointed with oil; afterwards, the sanctuary doors were closed and locked. No one but the head priest was allowed such close contact with the god. Those who came to the temple to worship only were allowed in the outer areas where they were met by lesser clergy who addressed their needs and accepted their offerings. During festivals, however, the statues of the god were taken out of the sanctuaries and carried about in the streets or onto boats on the Nile. Public religious festivals were key events, offering exciting spectacles and mass rituals and celebrations. The representation of gods via sacred statues that were the centres of local cult worship was a phenomenon that went far beyond Egypt, common in one form or another throughout the Mediterranean.

Law and Judgement

While religion offered legitimacy to imperial rule, this legitimacy was also always connected to the government’s role as the provider of law and justice. This can be seen very clearly in the oldest fully surviving law code, that of the Babylonian king Hammurabi, who ruled a Mesopotamian empire from 1795-1750 BCE. Hammurabi’s laws were inscribed on stone pillars, called steles, some of which have survived to the present day. The upper part of the stele depicts Hammurabi standing in front of the Babylonian god of justice Shamesh, emphasizing the divine origin of Hammurabi’s rule and laws. The lower portion of the stele contains a ‘prologue’, the collection of 282 laws, and an ‘epilogue’. The prologue and epilogue contain, among other things, claims about the divine origins and justic of Hammurabi’s rule, stating, for example, that “Anu and Bel (two gods) called by name me, Hammurabi, the exalted prince, who feared God, to bring about the rule of righteousness in the land, to destroy the wicked and the evil-doers; so that the strong should not harm the weak, so that I should rule over the black-headed people (meaning Mesopotamians) like Shamash and enlighten the land, to further the well-being of mankind.”

One particularly influential principle in the code is the law of retaliation, which demands “an eye for an eye, a tooth for a tooth.” The code listed offenses and their punishments, which often varied by social class, showing that there were legal differences between aristocrats and commoners, and also different statuses within these social classes. While symbolizing the power of the King Hammurabi and associating him with justice, the code of law also attempted to unify people within the empire and establish common standards for acceptable behavior. Some laws from Hammurabi’s Code include:

6. If anyone steal the property of a temple or of the court, he shall be put to death, and also the one who receives the stolen thing from him shall be put to death.

8. If any one steal cattle or sheep, or an ass, or a pig or a goat, if it belong to a god or to the court, the thief shall pay thirtyfold therefore; if they belonged to a freed man of the king he shall pay tenfold; if the thief has nothing with which to pay he shall be put to death.

15. If any one receive into his house a runaway male or female slave of the court, or of a freedman, and does not bring it out at the public proclamation of the major domus, the master of the house shall be put to death.

53. If any one be too lazy to keep his dam in proper condition, and does not so keep it; if then the dam break and all the fields be flooded, then shall he in whose dam the break occurred be sold for money, and the money shall replace the corn which he has caused to be ruined.

129. If a man’s wife be surprised (having sex) with another man, both shall be tied and thrown into the water, but the husband may pardon his wife and the king his slaves.

137. If a man wish to separate from a woman who has borne him children, or from his wife who has borne him children: then he shall give that wife her dowry, and a part of the usufruct of field, garden, and property, so that she can rear her children. When she has brought up her children, a portion of all that is given to the children, equal as that of one son, shall be given to her. She may then marry the man of her heart.

195. If a son strike his father, his hands shall be cut off.

196. If a man put out the eye of another man his eye shall be put out.

197. If he break another man’s bone, his bone shall be broken.

198. If he put out the eye of a freed man, or break the bone of a freed man, he shall pay one gold mina.

199. If he put out the eye of a man’s slave, or break the bone of a man’s slave, he shall pay one-half of its value.

202. If any one strike the body of a man higher in rank than he, he shall receive sixty blows with an ox-whip in public.

203. If a free-born man strike the body of another free-born man or equal rank, he shall pay one gold mina.

205. If the slave of a freed man strike the body of a freed man, his ear shall be cut off.

These laws prescribe a variety of fines, corporal punishments, mutilations, and liberal use of the death penalty. They offer insight into quite diverse aspects of Mesopotamian culture of the time. Law 129 punishes adultery by a woman by drowning both her and the male adulterer, but allows for mercy to be shown at the husband’s discretion. Law 195 seems to enforce patriarchal authority over the household, threatening harsh punishment to a son who strikes his father. Law 137 requires that a man separating from his wife or the mother of his children return her dowry and provide further support for her and her children. Law 15 makes harboring escaped slaves punishable by death, suggesting both strong government support for the institution of slavery and illustrating the harsh means by which social hierarchy was enforced under Hammurabi.

No similar law code has survived for ancient Egypt, and we should not assume that Hammurabi’s laws were especially representative of ancient laws generally. But we do have some understanding of both the laws of ancient Egypt and the institutions which administered and enforced them. The courts which administered the law were the seru (a group of elders in a rural community), the kenbet (a court on the regional and national level) and the djadjat (the imperial court). The vizier, who was the highest ranking bureaucrat in the government under the king, was the supreme judge, responsible for ensuring that ma’at was mantained. If a crime were committed in a village and the seru could not reach a verdict the case would go up to the kenbet and then possibly the djadjat (but this seems a rare occurrence). Usually, whatever happened in a village was handled by the seru of that town.

Many of the cases heard involved disputes over property following the death of the patriarch or matriarch of a family. There were no wills in ancient Egypt but a person could write out a transfer document making clear who should receive which portions of property or valuables. Then as now, however, these documents were often disputed by family members who took each other to court. There were also instances of domestic abuse, divorce, and infidelity addressed by the legal system.

There were no lawyers in ancient Egypt. A suspect was interrogated by the police and the judge in court and witnesses were brought in to testify for or against the accused. Since the prevailing belief was that a person who had been charged was guilty until proven innocent, witnesses were often beaten to make sure they were telling the truth. Once one had been charged with a crime, even if one were finally found innocent, one’s name was kept on record as having been a suspect. As such, public disgrace seems to have been as great a deterrent as any other punishment. Even if one were completely exonerated of all wrong-doing, one would still be known in one’s community as a former suspect.

It was because of this that people’s testimony regarding one’s character – as well as one’s alibi – was so important and why false witnesses were treated so harshly. Anyone who purposefully and knowingly lied to the court about a crime could expect punishment ranging from amputation to death by drowning. One might falsely accuse a neighbor of infidelity for any number of personal reasons and, even if the accused were found innocent, they would still be disgraced. A false charge, therefore, was considered a grave offense and not only because it disgraced an innocent citizen but because it called into question the efficacy of the law.

By enforcing laws and maintaining order, empires both enhanced their legitimacy and suppressed potential threats to their authority. Banditry, corruption, disorder and crime all undermined respect for the government and forced the population to rely on themselves for safety. But harsh laws or heavy taxes could also engender hatred of and resistance to the government, creating displaced people and refugees hiding from and defying imperial authority. Such outlaws were also prospective rebels, and although most popular uprisings against ancient governments were suppressed and ruthlessly punished, on some occasions they could be a potent threat to the survival of the empire.

Women: Law, Religion, Work, and Family

Compared to women in many other ancient societies, women in ancient Egypt had considerable legal rights and freedoms.

Egyptologist Barbara Watterson writes:

In ancient Egypt a woman enjoyed the same rights under the law as a man. What her de jure [rightful entitlement] rights were depended upon her social class not her sex. […] An ancient Egyptian woman was legally capax [competent, capable]. In short, an ancient Egyptian woman enjoyed greater social standing than many women of other societies, both ancient and modern. (16)

This social standing was complex, however, and subject at times to limitations. Egypt’s gender roles meant that women were usually defined primarily by their husbands and children, while men were defined by their occupations. This difference could leave women more economically vulnerable than men. For example, in the village of craftspeople who worked on the pharaoh’s tomb at Deir el Medina, houses were allocated to the men who were actively employed. This system of assigning housing meant that women whose husbands had died would be kicked out of their homes as replacement workers were brought in. Despite such vulnerability, Egyptian law treated the sexes similarly in many respects. Cases involving infidelity were filed by both sexes and the punishment for the guilty could be severe. A husband whose wife had an affair could forgive her and let the matter go or he could prosecute. If he chose to take his wife to court, and she were found guilty, the punishment could be divorce and amputation of her nose or death by burning. An unfaithful husband who was prosecuted by his wife could receive up to 1,000 blows but did not face the death penalty.

Egyptian women could own property, and tax records show that they often did. Egyptian women could also take cases to court, enter into legally binding agreements, and serve actively as priestesses. Women could sue for divorce as easily as men and could also bring suits regarding land sales and business arrangements. There were also female pharaohs, most famously Hatshepsut who ruled for twenty years in the fifteenth century BCE. One last, perhaps surprising, legal entitlement of ancient Egyptian women was their right to one-third of the property that a couple accumulated over the course of their marriage. Married women had some financial independence, which gave them options to dispose of their own property or divorce. Therefore, while women did face constraints in terms of their expected roles and had their status tied to the men in their families, they nevertheless enjoyed economic freedoms and legal rights not commonly seen in the ancient world.

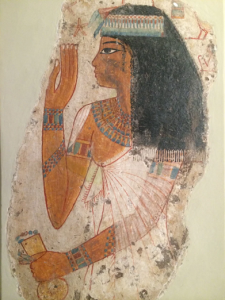

The respect accorded to women in ancient Egypt is evident in almost every aspect of the civilization from religious beliefs to social customs. As has been explained, one of the central values of ancient Egyptian civilization was ma’at – the concept of harmony and balance in all aspects of one’s life. This ideal was the most important duty observed by the pharaoh who, as the mediator between the gods and the people, was supposed to be a role model for how one lived a balanced life. This symmetry of balance can also be seen in gender roles throughout the history of ancient Egyptian civilization.

Women could be scribes and also priestesses, usually of a cult with a feminine deity. The clergy of Isis, for example, were female and male. It must be noted that the designation ‘cult’ in describing ancient Egyptian religion does not carry the same meaning it does in the modern day. A cult in ancient Egypt would be the equivalent of a sect in modern religion.

People interacted with their deities primarily at festivals where women regularly played important roles. Aside from festivals, people would pray to the gods at home in front of personal shrines, thought to have been erected and kept by women as part of their household responsibilities. Each home had its own altar which would usually have an image or statue of a patron god or goddess and offerings such as food, libations, and flowers would be placed there along with prayers making requests or giving thanks. These altars honored the family’s protective deities and ancestors, and most often featured statuettes, images, and amulets of goddesses, such as those of the hearth, home, childbirth, children, and women’s secrets, related to the essential roles that women played in the daily life of the household.

Egyptian women were free to seek work outside the home as well. Tombs and papyri depict women at various occupations in addition to scribes and priestesses, such as singers, musicians, dancers, concubines, servants, beer brewers, bakers, weavers, cooks, sandal-makers, professional mourners, and seers. Women were also doctors, dentists, estate owners, property and business managers, and merchants. Women in some professions such as brewers frequently supervised male workers.

Female doctors were highly respected in ancient Egypt. Female physicians would have seen both male and female patients, and female dentists would have worked on alleviating the tooth pain of men as often as women. The medical school in Alexandria was attended by students from many other countries. The Greek physician Agnodice, denied an education in medicine in Athens because of her sex, studied in Egypt c. 4th century BCE and then returned to her home city disguised as a man to practice.

Most Egyptian women were groomed for marriage and being homemakers. There was no marriage ceremony in ancient Egypt; a woman simply moved with her belongings to the house of her husband or her husband’s family. For most Egyptians, marriage was monogamous and for life. In ancient Egypt, it was understood that the man was the head of the household and had the final word in decisions, but there is plenty of evidence to suggest that men consulted with their wives regularly and that the marriage was seen as an equal partnership.

A stable marriage contributed to a stable community, and so it was in the best interests of all for a couple to remain together. Further, the ancient Egyptians believed that one’s earthly life was only a part of an eternal journey, and one was expected to make one’s life, including one’s marriage, worth experiencing forever. In art and in tomb paintings, women, no matter their class, were almost always shown as youthful with an emphasis on the female form, depicting the individual who, after all, would be young and beautiful again after shedding the body and entering the afterlife of the Field of Reeds.

Reliefs, paintings, and inscriptions of daily life depict husbands and wives eating together, dancing, drinking, and working the fields with one another. Even though Egyptian art is highly idealized, it is apparent that many people enjoyed happy marriages and remained together for life.

Love poems were extremely popular in Egypt praising the beauty and goodness of one’s girlfriend or wife and swearing eternal love in phrases very like modern love songs:

I shall never be far away from you

While my hand is in your hand

And I shall stroll with you

In every favourite place.

(Lewis, 201)

The speakers in these poems are both male and female and address all aspects of romantic love. The Egyptians took great joy in the simplest aspects of life, and one did not have to be royalty to enjoy the company of one’s lover, wife, family, or friends.

While in practice, men held positions of authority such as pharaoh, governor, vizier, or general–save for some notable exceptions in the monarchy– and a man was considered the head of the household, within this patriarchal society Egyptian women exercised considerable power and independence. They certainly had greater opportunities for personal advancement and financial gain than women in neighboring civilizations.

Old Kingdom of Egypt: Monuments and Power

Returning to the discussion on empire, another area in which ruling power, bureaucracy, and religion, come together is in the vast monumental architecture that marks the advent of civilizations, and which in Egypt is shown in astounding ways with the construction of the pyramids of Giza, beginning in the Old Kingdom period. The pyramids of Egypt required unprecedented bureaucratic efficiency to organize the labor force who built them, and this bureaucracy could only have functioned under a strong central government. By the 2600s BCE, the power of the pharaohs and the sophistication of the state in Egypt were such that the building of large-scale stone architecture became possible. The Old Kingdom (approximately 2613–2181 BCE), is best known for the massive stone pyramids that continue to awe visitors to Egypt today, many thousands of years after they were built.

The Ages of Egypt.

6000–3150 BCE Pre-Dynastic Egypt

3150–2613 BCE Early Dynastic Egypt

2613–2181 BCE Old Kingdom Period

2181–2040 BCE First Intermediate Period

2040–1782 BCE Middle Kingdom Period

1782–1570 BCE Second Intermediate Period

1570–1069 BCE New Kingdom Period

1069–525 BCE Third Intermediate Period

These names for the different eras of ancient Egypt’s history were developed by scholars in the nineteenth century. “Kingdom” describes a period of high centralized state organization. “Intermediate” describes a time of weak centralized state organization. While flawed in some ways, the labels continue to influence the way we understand the expansive chronology of ancient Egyptian history and have been used throughout this chapter.

Ancient records of this period of pyramid-builders are scarce, and historians regard the history of the era as literally ‘written in stone’ and largely architectural, in that it is through the monuments and their inscriptions that scholars have been able to construct a history.

The pyramids were tombs for the pharaohs of Egypt, places where their bodies were stored and preserved after death. The preservation of the body was important and was directly related to Egyptian religious beliefs that a person was composed of a number of different elements. These included the Ka, which was a person’s spiritual double. After the physical body died, the Ka remained but had to stay in the tomb with the body and be nourished with offerings. The Ba, another element of the person, was also a type of spiritual essence, but it separated from the body after death, going out in the world during the day and returning to the body each night. The duty of the Ahk, yet another type of spirit, was to travel to the underworld and the afterlife. The belief in concepts like the Ka and Ba was what made the practice of mummification and the creation of tombs important in Egyptian religion. Both elements needed the physical body to survive.

Before the construction of the pyramids, tombs and other sizeable architectural features were built of mud-brick and called mastabas. But during the Early Dynastic reign of the pharaoh Djoser (c. 2670 BCE), a brilliant architect named Imhotep decided to build a marvelous stone tomb for his king. Originally, it was intended to be merely a stone mastaba. However, Imhotep went beyond this plan and constructed additional smaller stone mastabas, one on top of the other. The result was a multitiered step pyramid, considered to be a first pyramid of Egypt. Surrounding it, Imhotep built a large complex that included temples.

The step pyramid of Djoser was revolutionary, but the more familiar smooth-sided style appeared a few decades later in the reign of Sneferu (c. 2613-2589 BCE), when three pyramids were constructed. The most impressive has become known as the Red Pyramid, (so called because of the use of reddish limestone in construction); it was built on a solid base for greater stability, rising 344 feet (105 meters) over the surrounding landscape. The Red Pyramid is considered the first successful true pyramid built in Egypt. Originally it was encased in white limestone, which fell away over the centuries and was harvested by locals for other building projects.

Sneferu was a much-admired pharaoh, who commanded great respect from his people.

According to historian Barbara Watterson:

He led military expeditions to Sinai to protect Egypt’s interests in the turquoise mines, and to northern Nubia and Libya, bringing back from Nubia 7,000 prisoners and 200,000 head of cattle and, from Libya, 11,000 prisoners and 13,100 head of cattle. The prisoners were probably used to augment the work-force in quarries. In succeeding generations, Sneferu acquired the reputation of being beneficent and liberal and, according to a story recounted in the Westcar Papyrus, capable of the common touch in addressing one of his subjects as ‘my brother.’ (51)

King Sneferu, through his military expeditions and judicious use of resources, established a powerful central government which produced the kind of stability necessary for his vast building projects. Following the example of Djoser’s complex at Saqqara, Sneferu had mortuary temples and other buildings constructed around his pyramids with priests taking care of the day-to-day operations once the Red Pyramid was finally completed. All of this argues for a stable society under his reign which he left to his son, Khufu, when he died.

The next pharaoh Khufu (2589-2566 BCE) was known as Cheops by the ancient Greek writers and is best known for his Great Pyramid at Giza.

The Great Pyramid was 756 feet long on each side and originally 481 feet high. Its base covers four city blocks and contains 2.3 million stone blocks, each weighing about 2.5 tons. It is the only one of the structures at Giza which was considered one of the ancient Seven Wonders of the World and with good reason: until the Eiffel Tower was completed in 1889 CE, the Great Pyramid was the tallest structure on earth built by human hands. Even more than the Pyramid of Djoser, the Great Pyramid is a testament to the organization and power of the Egyptian state.

The Greeks in their writings depicted Khufu as a tyrant who oppressed the people and forced them to work for him against their will. Most likely, the ancient Greeks who wrote of “Cheops” as a tyrant took their lead from Herodotus, who writes that Khufu brought to Egypt “every kind of evil” for his own glory, forcing “a hundred thousand men at a time, for three months continually” to work on his pyramid (II.124). Herodotus’ claims, though, have been discredited through Egyptian texts which admire and praise Khufu’s reign, and physical evidence, which suggests the workers on the Great Pyramid were well cared for and performed their duties as part of a community service, as paid laborers, or during the time the Nile’s flood made farming impossible. During his reign, Egypt grew even more wealthy through his military campaigns against Nubia and Libya and his very prosperous trade agreements. He also devoted resources to improving the lives of his subjects through agricultural innovations.

Contrary to the popular belief that the pyramids of Giza were built by slave labor, they were actually constructed by Egyptians, many of whom were highly skilled workers who were paid for their time. Although slave laborers from Nubia, Libya, even Canaan and Syria, were most likely used in the quarries cutting rock or in the gold mines, they would not have been entrusted to create the pharaoh’s eternal home. No slave quarters have been discovered at Giza. Worker’s quarters, supervisor’s houses, overseer’s homes have all been found and make clear that the work done at the Giza plateau in the Old Kingdom was performed by Egyptians working for compensation.

The pyramid of the pharaoh Khafre (2558-2532 BCE), Khufu’s son and eventual successor, is the second-largest at Giza and his complex almost as grand as his father’s. He is also thought to be the face of the Sphinx, the largest monolithic statue in the world, depicting a reclining lion’s body with the head and face of a king. Traditionally this king’s face is accepted as Khafre, but others claim it may actually be Khufu’s. Little is known of Khafre’s reign but Egyptian texts indicate he followed his father’s model of government in placing power in the hands of his closest family members and maintaining a tight control over policies and laws.

The Old Kingdom period also brings a significant shift in the way in which the Egyptians viewed the connection between their Pharaoh and the gods. Khafre associated himself with the god Horus as earlier kings had done, and the Sphinx was considered an image of the king as the god Harmakhet (‘Horus in the Horizon’). Unlike the kings of the Early Dynastic Period, however, who were seen to be the living embodiment of the god Horus, Khafre – and those who came after him – referred to himself as a “Son of Horus”, associated with the god but not the living god himself. The power of interpreting the will of the gods, though still within the king’s sphere of influence, grew increasingly to be the provenance of the priests who served those gods.

The pharaohs were diverting enormous resources to their mortuary monuments and complexes. As the pyramid and temple complexes became larger and more numerous during the Old Kingdom, so too did the number of priests and administrators in charge of managing them. This required that ever-increasing amounts of wealth be directed toward these individuals and away from the central state. The temples and shrines came to be no longer under the king’s control but that of the priests who administered them.

Over time, the management of the large Egyptian state also required more support from the regional governors or nomarchs and administrators of other types, which meant the pharaohs had to delegate more authority to them. By around 2200 BCE, priests and regional governors possessed a degree of wealth and power that rivaled and sometimes surpassed that of the nobility. For all these reasons and more, centralized power in Old Kingdom Egypt weakened greatly during this time, and scholars since the nineteenth century have referred to this era as the First Intermediate Period—a time of decentralization before the next rise of a highly centralized state power characterizing the Kingdom periods of Egypt.

New Kingdom of Egypt: The Height of Power

The New Kingdom (c. 1570- c.1069 BCE) reestablishes centralized state organization, following the disunity of the Second Intermediate Period (c. 1782-1570 BCE). When centralized power in Egypt declined during the late Middle Kingdom, Egyptians were less able to enforce their borders and preserve their state’s integrity. More and more outsiders flowed into the Nile delta from Canaan, and within several decades were so numerous in Lower Egypt that by about 1720 BCE, some of their chieftains began to assert control over local areas. Around 1650 BCE, one group of recently arrived Canaanites known as the Hyksos overthrew the remaining Egyptian local rulers and assumed control of the entire delta.

The Hyksos ruled the Nile delta for more than a hundred years. Depictions of this period according to Egyptian tradition describe wanton destruction, including the enslavement of Egyptians, the burning of cities, and the desecration of shrines. However, the archaeological record as well as evidence from the time show this to be literary exaggeration, intended to contrast the greatness of a strong, unified Egypt of the New Kingdom against the disunity that came before it.

Historical evidence indicates that the Hyksos readily adopted Egyptian culture and relied on Egyptian patterns of rule, even included Egyptians in their bureaucracies. In addition, Hyksos rule appears to have benefited Egypt in a number of ways, bringing sophisticated bronze-making technology into Egypt from Canaan, for example. The advantages of bronze over softer materials like copper were obvious to Egyptians, and the metal became the material of choice for weapons and armour. The Hyksos also introduced composite-bow technology which made archery faster and more accurate, and most importantly, the horse-drawn, lighter-weight chariot with spoked wheels. By the 1500s BCE, horse-drawn chariots with riders armed with composite bows had become a staple of the Egyptian military, just as they were across all the powerful empires and kingdoms of the Near East.

The Hyksos did not dominate all of Egypt, though. In the Theban kingdom, indigenous Egyptian rulers still held sway and they resisted Hyksos control of Lower Egypt. Beginning in the 1550s BCE a string of Theban rulers went on the offensive against the Hyksos. Eventually the Egyptian Pharaoh Ahmose I (c. 1570-1544 BCE) succeeded in driving the Hyksos out and quickly set about securing and then expanding the borders of Egypt to provide a buffer zone against any further invasions. Ahmose’s military victories ushered in the next period of Egypt’s greatness.

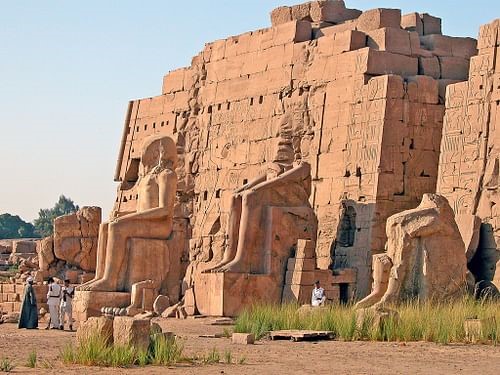

The New Kingdom represents the pinnacle of Egypt’s power and influence in the Near East, as it reconquered territory it had lost following the collapse of the Middle Kingdom, and extended its reach deep into the Libyan Desert, far south into Nubia, and eventually east as far as northern Syria. This expansion made Egypt the Mediterranean superpower of its day. It is not surprising, then, that the pharaohs of this period are some of the best known, such as Hatshepsut, Thutmose III, Amenhotep III, Akhenaten and his wife Nefertiti, Tutankhamun, and Ramesses II (The Great). They commanded massive and highly trained armies and had at their disposal a seemingly endless supply of wealth, with which they constructed some of the most impressive architectural treasures of the entire Near East.

Ahmose I left a stable political and economic situation for his successor Amenhotep I (c. 1541-1520 BCE), who maintained his father’s policies securing the borders but made no serious attempts at expanding Egypt’s territory. He was succeeded by Thutmose I (1520-1492 BCE) whose campaigns broadened Egypt’s reach, and who erected numerous temples and monuments throughout Egypt. We know little about the reign of his son Thutmose II (1492-1479 BCE) who was overshadowed by his more powerful half-sister and wife, Hatshepsut.

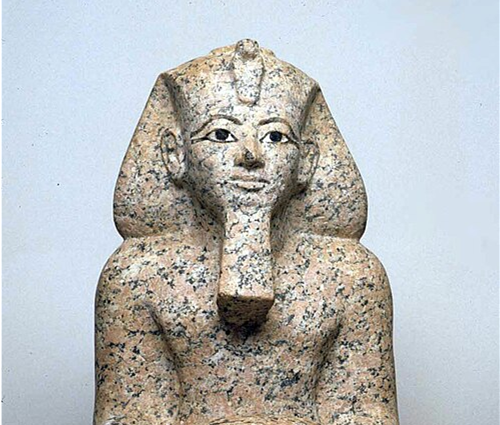

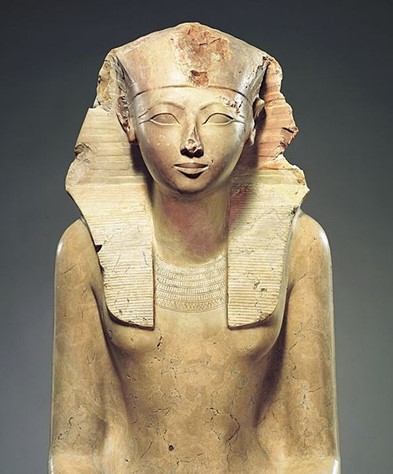

Hatshepsut (1479-1458 BCE) is among the most powerful and successful of the New Kingdom monarchs. She had a daughter, but no son. Thus, when her husband Thutmose II died in 1479 BCE, his two-year-old son conceived by a secondary wife assumed the throne as Thutmose III. Acting as regent for the infant pharaoh, Hatshepsut inaugurated a very unusual period in Egyptian history. Rather than rule in the background, she proclaimed herself co-regent with her stepson and soon assumed the title of pharaoh. Statues of her from this period often depict her wearing the pharaonic headdress and ceremonial beard and give her the broad torso more typical of a male. Inscriptions clearly indicated that she was a woman, but the symbolic representations of Egyptian pharaohs were male.

As Egyptian pharaohs had done for many centuries, Hatshepsut also claimed divinity, but unlike earlier pharaonic claims, Hatshepsut included a detailed account of her heavenly origins: the god Amun-Re himself had assumed the form of Thutmose I and impregnated Hatshepsut’s mother, and he predicted that his child will rule all Egypt and elevate it to unsurpassed glory—Thutmose I thus recognized her divinity and named her his rightful successor. As both a woman and a regent, Hatshepsut was prudent to legitimize her rule in this way. And by all accounts, the heavenly prophecies about her reign proved accurate. For twenty-one years she ruled over a prosperous and dominant Egypt.

When Hatshepsut died in 1458 BCE, her stepson Thutmose III took control as sole ruler in Egypt for the first time. He was about thirty years old by then and had extensive military training. Leading his armies himself, he was able to neutralize the threats, launch a major raid across the Euphrates River, and take numerous Canaanite princes hostage so as to deter any uprisings from his vassals. He used the war chariot inherited from the Hyksos, as well as bronze weapons and superior tactics, to defeat the surrounding nations and expand Egypt’s domain further than it had ever reached in the past.

Thutmose III also began to eliminate his predecessor from history. He had Hatshepsut’s statues toppled and smashed, her name removed from monuments, and references to her erased from the official king lists. The evidence suggests that he harbored no ill will toward his stepmother. Instead, her erasure from the record was probably part of Thutmose’s process of paving the way for his son to rule in his own right in the future.

He was succeeded by his son Amenhotep II (1425-1400 BCE) who, like his father, inherited a strong and secure kingdom and improved on it. Successor, Amenhotep III (1386-1353 BCE), reigned over Egypt at one of its highest points culturally, politically, and economically. During his time, however, the priests of Amun began to acquire more and more wealth. They owned more land than the pharaoh and made use of it to further enrich themselves. Amenhotep III tried to quell their growing power by aligning himself with the god, Aten, represented by a sun disc. It seems he thought the power of the pharaoh behind the cult of Aten would increase the prestige of the priests of Aten at the expense of those of Amun.

Under Amenhotep III’s heir Amenhotep IV, the emphasis on the god Aten reached its fullest extent.

In the fourth or fifth year of his reign, Amenhotep IV changed his name to Akhenaten (1353-1336 BCE). The time of his reign has come to be known as the Amarna Period because the Egyptian capital was moved from Thebes to modern-day Amarna. He abolished the old religion – especially the cult of Amun – and elevated the god Aten to the position of the one true god.

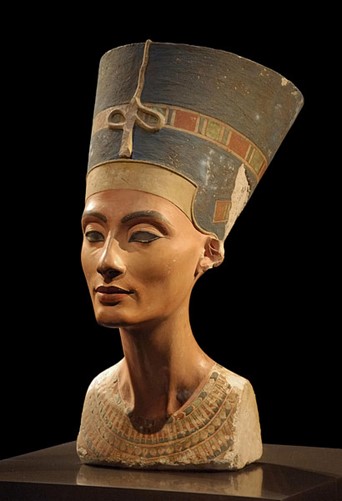

Only the Cult of Aten was viewed as a legitimate religious body; all the temples to the other gods were closed and Akhenaten ordered their representations to be destroyed and their names chiseled off monuments. At the great Temple of Amun at Karnak, which he also closed, he erected a temple to Aten. The pharaoh and his wife Queen Nefertiti (c. 1370-1336 BCE) now became the chief priests of a new cult built around Aten.

Many theories are proposed about Akhenaten’s motives for founding a new monotheistic religion, raging from a genuine effort at religious reformation, to sincere belief, or lunacy. He may have been reverting to older religious practice in which the king was the primary state deity. His reforms may have been his most effective solution to the problem of the growing power of the Cult of Amun. Akhenaten neutralized the power of the priests by outlawing their cult and banishing their god. In the emerging new religion, people were instructed to worship the pharaoh, making Akhenaten and Nefertiti intermediaries between the people and their god, eliminating the need for powerful priests.

One reason many questions about Akhenaten remain is that after he died, Egypt reverted to former religious traditions and attempted to erase this period from their history. Upon Akhenaten’s death he was succeeded by his young son Tutankhaten who swiftly changed his name to Tutankhamun (1336-1327 BCE), restored the religious center of Thebes, re-opened and repaired the temples, and brought back the old religion to Egypt. Although he initiated important reforms which stabilized the country, he is best known for his magnificent tomb discovered in 1922 by Howard Carter.

After Tutankhamun’s death at the age of 18 or 19, the general Horemheb came to power, devoting himself to restoring Egypt to its former glory. Horemheb (1320-1295 BCE) went to great lengths to wipe the Amarna Period from Egyptian history by destroying all the monuments and inscriptions of Akhenaten, including demolishing his temple to Aten at Karnak so thoroughly that no trace was left of it. The only way later historians learned of Akhenaten’s reforms was because Horemheb used the ruined monuments, stelae, and inscriptions as fill in other projects.

When Horemheb, the final pharaoh of this first dynasty of the New Kingdom, died childless, a military commander named Ramesses I took control and began a new dynasty. His heirs, sometimes called the Ramesside kings, worked hard to restore Egypt to greatness through impressive military and building campaigns. The greatest pharaoh of this period, and the last great pharaoh of the New Kingdom, was Ramesses II, who ruled Egypt for more than sixty-five years from 1279 to 1213 BCE.

Ramesses II defeated the Hittites at the Battle of Kadesh in 1274 BCE, a feat he was most proud of (although the battle was more of a draw), and signed the world’s first peace treaty. He also stopped an invasion by the Sea Peoples. He is routinely depicted as a great hunter and warrior-king. Egypt flourished under the reign of Ramesses II. He erected so many monuments and left so many inscriptions that there is virtually no ancient site in the country which does not bear some mention of his name.

The Great Temple at Abu Simbel was carved into the side of a mountain and includes four massive seated statues of Ramesses II himself. A passageway between the two center statues leads to chambers that stretch hundreds of feet into the sandstone. The engineers who designed the temple constructed it such that twice a year, the rays of the sun would enter the building at dawn and bathe the gods placed there in light.

Ramesses II lived to be 96 years old and, when he died, his people could not remember a time when he had not been king. His death caused wide-spread panic among the populace who were facing a future without Ramesses II as king.

His successor, Ramesses III, is considered to be the last “strong pharaoh” of the New Kingdom. The power of the priests of Amun had continued to grow once Horemheb revived the old religion, drawing revenue and influence away from the throne. By the time of Ramesses XI (1107-1077 BCE), the priests of Amun had established enough power to reign as pharaohs from Thebes.

This division of rule between Thebes in Upper Egypt and Ramesses XI’s reign in Lower Egypt resulted in the same kind of disunity which characterized the First and Second Intermediate Periods. Again there was no strong central government in Egypt and the policies of the past which had preserved the empire were no longer effective. Historian Margaret Bunson writes how the Ramessid pharaohs had “little military or administrative competence” after Ramesses III and that “the 20th Dynasty, and the New Kingdom, was destroyed when the powerful priests of Amun divided the nation and usurped the throne” (81).

Thus, Egypt entered the era known as the Third Intermediate Period, characterized by a steady decline in centralized power but without the subsequent rise and reconsolidation seen in previous Kingdom periods.

Fall

Each ancient empire, no matter how triumphant the inscriptions of its conquering monarchs or how vast its domains, eventually came to an end. What exactly constitutes the end of an empire can be a complex question — the most famous ‘fall’ of empire, that of Rome, has spawned endless debate, including many who question whether it ‘fell’ at all. What might seem like the end of an empire to its kings — their heirs being deposed from the throne or dying out — is not usually seen as especially significant by anyone else, if the replacement lineage keeps the same laws and institutions as before. Rather, we can identify several different ways empires can decline or end.

Loss of Territory/Dissolution – Imperial cores control a subjugated periphery: if the core loses control of part of the periphery the empire shrinks. If it loses all its imperial possessions, it may remain a state, but is no longer an imperial state. For example, Sargon of Akkad conquered his Mesopotamian empire from 2234-2279 CE and ruled from the city of Kish; his empire collapsed around 2154 CE under attacks from the Gutians, a neighbouring ethno-linguistic group. The Gutians did not found their own empire; rather, imperial authority dissolved entirely for a time and the largest states in Mesopotamia were once again city-states — mostly the same ones as before the Akkadian empire. Similarly, Athens for a time in the 5th century CE ruled an empire in the Aegean sea, but lost its empire in the Peloponnesian war against Sparta and with it its imperial status, although it continued to be an independent state until its conquest by Philip II of Macedon (see the next chapter for more details on this). In both these cases the metropole lost its imperial possessions and became once again an ordinary city-state.

Conquest – More dramatically, an empire can be defeated by an external rival such that the government of the imperial state is disbanded but the territory is incorporated into a new empire. The extent to which this constitutes a ‘fall’ of the empire can be disputed if the conquering group maintains many of the previous institutions and occupies a similar territory. In some cases, the old elites are even integrated into the new government, creating an additional layer of continuity between the ‘old’ empire and the new. The impact of conquest is more dramatic and undeniable when the empire is incorporated into a pre-existing empire, its core being subjugated and disempowered, now ruled from a new and distant metropole. Egypt, for example, was conquered by the Assyrian empire in 671 CE and ruled from Nineveh for forty years.

Destruction – In some cases, an empire can end more physically and finally. In order of increasing completeness: an empire’s capital can be destroyed together with the dissolution of its power; the core population can be substantially killed, dispersed or enslaved; or the core territory can be depopulated/abandoned. Obviously smaller imperial cores are more susceptible to destruction than large ones, and city states in particular can be completely annihilated if a conquering army so chooses. Empires can also be vulnerable over longer time-frames to destruction via climate change and environmental collapse, especially of they are based on islands or areas that are marginal for agriculture.

Transformation – Even if the government and culture of an empire never comes to a definitive end, the course of time inevitably brings change with it, and if an empire endures long enough it may change enough to be unrecognizable. For example, the Roman empire, although losing much of its western territory in the 5th century CE, maintained its eastern half until the final conquest of Constantinople in 1453 CE. But in that time period, the Eastern Roman Empire changed so much that it is barely recognizable when compared to the empire as it had existed in earlier times. It no longer spoke Latin; Christianity became central to its identity; it occupied a different location than when it originated; it replaced its republican government with absolute monarchy; its economy, culture, military and all transformed to a huge extent. One may genuinely question whether it is the ‘same’ empire that first conquered the Italian peninsula and fought wars against Carthage.

Rises and falls of Egyptian empires

Egyptian empire faced several different endings at different points in time. Egyptian imperial rule came to a kind of end for the first time in 2181, after the death of king Pepi II, who left no heirs. For nearly 150 years, local governors (nomarchs) were the real rulers along much of the Nile, and for a time there were two self-proclaimed royal lines, one based in Herakleopolis in the north, the other in Thebes to the south. This time is called the first intermediate period, and it can be fairly described as an end of the first unified empire of Egypt. But it was certainly not an end of Egyptian culture or government, and as far as falls of empires go it seems to have been very mild, with evidence suggesting that rural areas and cities outside of the old capital Memphis became wealthier and more prosperous than before. If the Nomarchs were able to keep order and uphold ma’at while demanding less labor and wealth from their subjects than the old pyramid-building kings in Memphis, then the end of the first Egyptian empire may well have been a blessing for most Egyptians.

This first fall of Egyptian empire is a dissolution of imperial authority, a risk that empires often face. Most common is the scenario where a very successful king/general conquers a large territory and creates and administers an empire that lasts for his lifespan, but begins to dissolve as soon as he dies and can no longer hold it together. In the absence of a strong centralizing force, very often regional aristocrats will take power for themselves, either informally or (if they can get away with it) formally as well, declaring themselves new kings or inventing fictitious royal connections. The old royal family loses its power, either exterminated by new rivals or clinging to some ancestral possessions and status. We will see similar dynamics again with subsequent empires such as Macedon, Rome, the Caliphates, and France.

The first intermediate period came to an end as the nomarchs of Thebes were able to conquer nearby nomes, style themselves kings of Egypt, and eventually defeat all their rivals. This begins the ‘Middle Kingdom’ of Egyptian history, where a succession of kings (and a reigning queen, Sobekneferu) presided over what seems to have been for Egypt a peaceful and prosperous period. Egyptian armies campaigned south of the cataracts and subjugated Nubia, and elaborate mortuary temples and inscriptions give archaeologists a wealth of insight into the culture, religion, and life of the time. Some papyrus narrative texts also survive from this time, such as the Tale of the Shipwrecked Sailor. This tells the adventures of a man who is shipwrecked and washed up on an island where he meets a gigantic talking snake. The snake ends up being friendlier than one might expect and helps him eventually return to Egypt with a ship full of treasure.

This second unified imperial Egypt is disrupted by the loss of territory to foreigners. A somewhat mysterious non-Egyptian group called the Hyksos come to rule over lower Egypt for about 100 years, from about 1650 to 1500 BCE. Once again, the impact on ordinary Egyptians seems to have been minimal: later Egyptian writers were outraged by this foreign domination but the Hyksos do not seem to have imposed their culture on their subjects or to have caused widespread violence or destruction. Upper Egypt continued under native rulers based in Thebes, and eventually these were able to drive out the Hyksos and reunify Egypt once and for all.

This third ancient Egyptian imperial period, the ‘New Kingdom’, engaged extensive imperial conquests along the Levant, the region bordering the east coast of the Mediterranean. These brought them into correspondence with other major and minor states and empires of the region — Babylon, Assyria, Mitanni, the Hittite kingdom, and the Phoenician cities of the coast. Many documents have survived, including the remarkable Amarna letters, a collection including hundreds of diplomatic letters from rulers throughout the area to the king of Egypt. Many of these date from the reign of the king Akhenaten, an unusual pharaoh who promulgated a new, monotheistic religion, the worship of the sun disc, Aten. A new, innovative art style was promulgated during his reign, but after his death the old religion reasserted itself, together with the traditional style. The New Kingdom once again fell into disunity after the death of Ramses XI in 1070 BCE, with the high priests of Amun in Thebes gradually taking control over the south of the country. This may have been connected to a larger spasm of violence and state collapse that engulfed the eastern Mediterranean at that time, connected to a somewhat mysterious coalition of violent invaders known as the “sea people”.

Other Empires of the Eastern Mediterranean

Despite the various rises and falls of various Egyptian dynasties, from the origins of civilization up until its conquest by Rome Egypt had a distinct and largely independent existence as a unified state, broken by much shorter periods of disunity. The history of its neighbours in Mesopotamia, Anatolia and Greece was less stable. Many different empires rose to prominence and collapsed in the second and first millenium, conquering their neighbours and dominating their region, until eventually their strength waned or they were outmatched by a new power. Some of the more significant and long lasting of these states included several empires based out of Babylon, the Hittites, the Mitanni, Assyria, the Minoans, the Myceneans, the city-states of the Phoenicians, the Medes, and Lydia.

Over time, the average size of these states increased, if not their longevity, and the largest such state ever to exist in the region was created by the conquests of the Persian ruler Cyrus in the middle of the 6th century BCE. Ancient Persia at its height under the dynasty he founded, the Achmaenids, stretched from the Indus river to Egypt and Anatolia, ruling a huge and diverse population via the combination of a complex bureacracy and an aristocratic Persian military elite. We know much more about Persia than many other previous empires because of its close encounters and rivalry with its Greek-speaking neighbours to the west, a fractious collection of city-states, the most powerful of which were Athens and Sparta. It is to this competitive, seafaring ancient Greek culture that we turn our attention in the next chapter.

This chapter is partly adapted from

Western Civilization: A Concise History by Christopher Brooks and is used under a CC BY-NC-SA license.

World History: Cultures, States and Societies to 1500 by Berger et. al. and is used under a CC BY-SA 4.0 license.

World History Encyclopedia: Ancient Egyptian Law by Joshua J. Mark and is used under a CC BY-NC-SA 4.0 license.

World History Encyclopedia: Ancient Egyptian Religion by Joshua J. Mark and is used under a CC BY-NC-SA 4.0 license.

Media Attributions

3.1 Narmer Palette by Nicolas Perrault III, in the public domain

3.2 A Map of Old Kingdom Egypt Showing its Administrative Divisions, Major Cities, and Some Trade Routes by Cattette is licensed under CC BY 4.0

3.3 Assyrian Wall Relief Showing Battering Ram, from Palace of Tiglat-Pilesser, c. 860 BCE by Soerfm, in the public domain

3.4 Anubis Sits in Judgement by Jeff Dahl, in the public domain

3.5 Hammurabi’s Code by Fritz Grögel is licensed under CC BY-SA 2.0

3.6 States Near New Kingdom Egypt by Electionworld is licensed under CC BY-SA 3.0

Women: Law, Religion, Work, and Family

This section is compiled and adapted from

World History Encyclopedia: Women in Ancient Egypt; Women’s Work in Ancient Egypt; The Gifts of Isis: Women’s Status in Ancient Egypt; by Joshua L. Mark and used under a CC BY-NC-SA 4.0 license

Text box citations in this source

Watterson, B. Women in Ancient Egypt. Sutton Publishing Ltd, 1994.

Lewis, J. E. The Mammoth Book of Eyewitness Ancient Egypt. Running Press, 2003.

Media Attributions for this section

Lady Tjepu By James Blake Weiner CC BY-NC-SA 4.0

Isis Wall Painting by The Yorck Project Gesellschaft für Bildarchivierung GmbH (GNU FDL)

Egyptian Woman Bearing Offerings by Jan van der Crabben CC BY-NC-SA 4.0

Beer Brewing in Ancient Egypt by The Trustees of the British Museum (Copyright)

Statue of Nykara and his Family by the Brooklyn Museum (Creative Commons BY)

Old Kingdom of Egypt: Monuments and Power

This section is compiled and adapted from the following:

World History Volume 1, to 1500 Section 3.3 Ancient Egypt by Ann Kordas, Ryan J. Lynch, Brooke Nelson, Julie Tatlock OpenStax and used under a CC BY 4.0 License

World History Encyclopedia: Old Kingdom of Egypt by Joshua J. Mark, published on 26 September 2016 and used under a CC-BY-NC-SA license

Textbox Citation from this source

Watterson, B. The Egyptians. Wiley-Blackwell, 1997

Media Attributions for this section

The Giza Pyramids under a CC BY-SA 3.0 Unported license.

Table: The Ages of Egypt used under a CC BY 4.0 license.