1 Human Beginnings and the Neolithic Revolution

Beginnings

Ancestors

Humans have been around for much longer than human history. History begins with writing, but writing is a recent technology — recent, at least, compared to the vast span of human prehistory, which extends back through the ice ages for hundreds of millennia.

Our species itself evolved in Africa from a complex lineage of upright-walking apes. The evolution of these ancestors of ours is shrouded by the passage of millions of years, and paleoanthropologists continually make new discoveries about human origins. This timeline shows the various species that were our nearest relatives and some of the major fossils that define our understanding of our family tree.

Humans have a lot in common with our ape relatives — chimpanzees, bonobos, orangutans and gorillas. But over the eight million or so years since our lineage diverged from other apes, our ancestors evolved one adaptation after another to form the basis of the distinctively humanoid way of life, which we shared with various now-extinct ancestors and cousins in our genus, Homo. The starting point for this divergence seems to have been the emergence of upright walking, which we started to do at least 7 million years ago. We evolved from ancestors adapted to live in trees, but upright walking enabled us to thrive in the open grasslands of Africa, a new environment for apes.

No longer relying so much on the need to climb and swing acrobatically through the forest, our hands evolved for holding objects, tool use and, eventually, tool manufacture. The earliest manufactured stone tools date back 2.6 million years, but it is quite possible that sophisticated tool use came long before our ancestors began to manufacture tools in stone. Chimpanzees, after all, use simple tools. Manufacturing stone tools is complex and difficult compared to working in wood, and even more so than using found objects such as rocks, bones, and sticks. This is one of the many areas where the limitations of our knowledge are tied to evidence that may well be lost forever: if our ancestors millions of years ago wove elaborate baskets or made complex wooden traps, those creations have been destroyed by the intervening ages.

Homo Erectus was one of the most successful and long-lived hominid species. They evolved nearly 2 million years ago and spread across Africa, south Asia and Indonesia (which was connected to Asia by land during the numerous ice ages). They developed a more complex stone tool-kit with which they hunted large mammals such as elephants and rhinos. They lived and travelled in small groups. Scientists do not know whether they had language, art, or spiritual beliefs — they may have, but evidence is scanty. Their success in hunting huge and dangerous animals with very simple technology suggests that, at the least, they were excellent at social co-operation. One remarkable site in Kenya preserves the footprints of a small group of them walking across a mud flat, a moment in time preserved for a million and a half years.

Our own subspecies, Homo sapiens sapiens, emerged in Africa about 300,000 years ago – the oldest known specimens were discovered in Morocco in 2017. These people developed technology much more complex and varied than had ever existed before, including needles, fishhooks, ocean-going boats, and fire. They were thus able to hunt and protect themselves from animals that had far better natural weapons, and (through cooking) eat food that would have been indigestible raw. Likewise, animal skins served as clothes and shelter, allowing them to eventually spread further north into the sub-arctic terrain that adjoined the continent-sized glaciers of the ice ages.

These physically indistinguishable ancestors of ours coexisted with other populations of hominids, most famously the Neanderthals (Homo sapiens neandertalensis) who inhabited northwestern Eurasia. Neanderthals flourished between about 400,000 and 40,000 years ago, and were physically larger and stronger than Homo sapiens sapiens, adapted to survive in colder conditions. Neanderthals congregated in small groups and had sophisticated technology and social lives: building shelters, making art, burying their dead and using fire for warmth and cooking. Aside from the Neanderthals other hominids who coexisted with our ancestors were the previously mentioned Homo erectus, Homo naledi who inhabited southern Africa, the small Homo floresiensis whose fossils have only been found on one tiny Indonesian island, and the mysterious Denisovans, who lived in eastern Eurasia and are known almost only from DNA evidence.

Migration and Adaptation

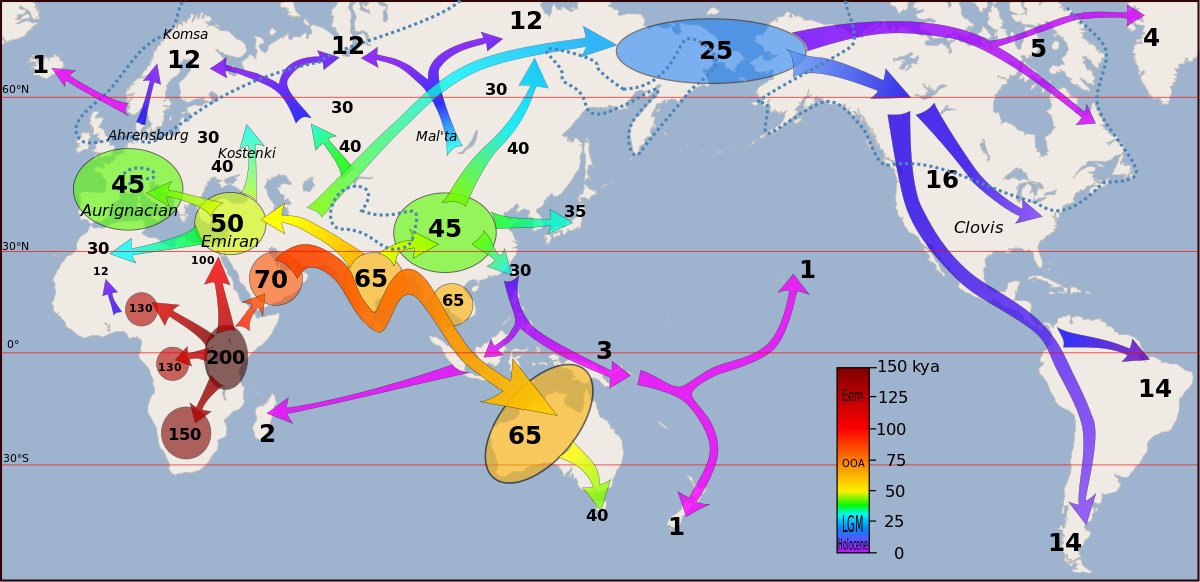

As can be seen in the map above, humans first spread throughout Africa. About 70 millennia ago some of them crossed over into the Arabian peninsula. All non-African human populations originate from this group, thought to be possibly as few as a thousand individuals. Their descendents spread east along the coast of the Indian ocean as far as Australia, and then about forty thousand years ago some began to move further north, hunting mammoths and sheltering in hide tents. Everywhere they went, these humans interbred with but gradually displaced the previous hominid inhabitants, leaving traces of Neanderthal and Denisovan DNA in our genomes.

Foraging culture

Our ancestors lived by foraging. This simple label conceals both the incredibly complex and sophisticated techniques by which each foraging culture thrives in its environment, and the vast diversity of cultures that emerged over the millennia of human expansion. The ability of our ancestors to spread across the entire world was an amazing accomplishment, made possible by their ability to adapt their culture over time to new environments. One of the most misleading caricatures of our foraging ancestors is that they were simple ‘cavemen’, using primitive language and inadequate technology to scrape out a desperate living from the wilds. There is no reason to think that the humans who lived hundreds of thousands of years ago were any less intelligent than we are today, and their cultural practices allowed them to flourish in their ancestral environments.

This included inventing new technologies, but also creating new knowledge and developing new and sophisticated strategies of survival. Humans use language and imitative learning to build up and pass on a dense and interconnected cultural system, which includes technologies, spiritual beliefs, art and music, practical knowledge, and social rules. Their cultural systems allow foragers to survive and thrive. By gradual cultural adaptation and diversification human foragers eventually occupied almost the entire planet except Antarctica.

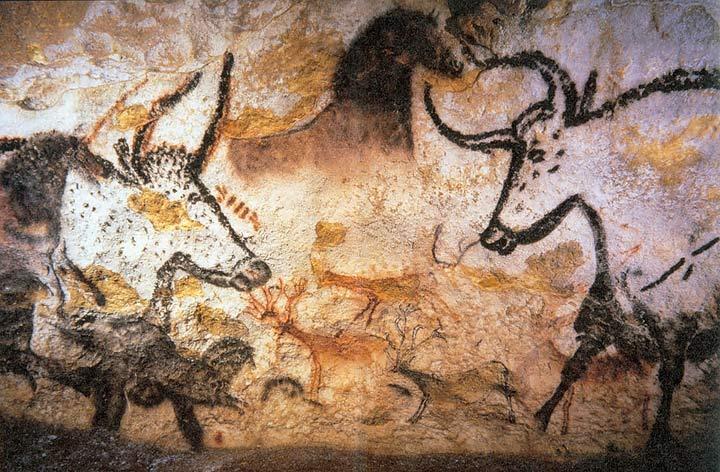

Art is an especially human development: some art may predate our species, but it is with Homo sapiens sapiens that the artistic finds begin to become common and unmistakable, including painting, jewellery, sculpture, and musical instruments. Homo sapiens painted on the walls of caves, most famously in the Lascaux caves in southern France. They also sometimes buried their dead in prepared grave sites with objects such as tools and even elaborate clothes, suggesting that they had spiritual beliefs. These belief systems were integrated with their technology and their encyclopedic knowledge of the plants and animals of their environment into a coherent worldview and way of life.

1.3 Part of the Lascaux cave paintings in southern France.

Foraging life, although very diverse, shared certain tendencies. Communities were fairly small and consisted mostly of relatives, but they had close ties with other local groups as well as larger clan and tribe structures. These loose, large relationships unified people for rituals, marriage exchanges, trade, and sometimes conflict. There were usually no formal or hereditary leadership positions, but temporary roles leading important tasks such as hunts, rituals, and other communal activities were common, and could be important and prestigious.

These otherwise unspecialized societies often divided their members into two genders with different roles and responsibilities. The gender-roles of foragers were connected to the vulnerability of children, who need adult supervision and protection. Foraging mothers typically breastfed their children until they were 3 or 4 years of age, and many women would have had a dependent, breastfeeding child to care for during the majority of their adult years as a result of successive pregnancies. As a result of this, feminine tasks in foraging societies tend to be ones that can be carried out while minding small children.

Despite this commonality, the gendering of tasks among foragers is very diverse. Hunting was a characteristically masculine activity (although by no means exclusively so); child-rearing and the gathering of food plants characteristically feminine. Some rituals were gendered, especially the initiation into adulthood, which in a wide variety of forms can be found in foraging cultures worldwide. But ritual roles generally, various crafts, and food processing tasks might be gendered or not depending on the particular practices of the local culture, in an interlocking system that ensured that the community could survive and flourish.

Technologies: Weaving The earliest evidence of weaving comes from the central European site of Dolní Věstonice, a culture of foraging mammoth hunters. This Gravettian site shares its material technology with groups that occupied Europe from 33,000 to 22,000 years ago. Impressions of woven materials were found on surviving clay surfaces that date back 27,000 years, and show many different techniques and materials, including baskets, rope, nets, and woven cloth. Woven materials do not survive well over millennia, and weaving could either be as recent as Dolní Věstonice or could predate our species.

Weaving requires long and flexible threads or cords. These can be naturally occurring, such as tall grass or bark fibres, or manufactured via twisting or spinning together shorter fibres. Weaving can create a huge variety of tools and objects, making it one of the most important and useful production technologies ever developed by our species. Nets are invaluable for catching fish and small game, providing a foundational subsistence tool for many foraging cultures. Cloth production eventually became one of the most important economic activities in agricultural societies, consuming huge amounts of labour and figuring heavily in trade.

An important but contentious topic is the prevalence of violence and warfare among foragers. Extreme views have depicted them as pacifistic and gentle, or as brutish, cannibalistic and warlike. Both of these are distortions. It is clear that large-scale battles and armies did not exist among foragers, and that some foraging cultures had little or no organized violence of any kind. But organized violence is not the only kind of violence, and it seems that murder and violent aggression were very common in most hunter-gatherer societies. People relied on their relatives and friends for protection from strangers, and on negotiation and mediation to keep peace among themselves.

As effective as such efforts could be, dying by violence was a serious risk in all hunter-gatherer societies. Raids or harassment by a more powerful, aggressive neighbouring group might gradually destroy a band, or force them to abandon their ancestral lands. This may have been how our ancestors displaced and eventually extinguished the Neanderthals and other hominid species, but there is no way to know for certain. Violence, like hunting (itself violent) was a characteristically but not exclusively masculine activity, and among cultures that engaged in raiding and warfare, successful fighters could gain glory and respect.

Although relations between neighbouring bands and tribes could be hostile, there is also clear evidence of trading networks among hunter-gatherers that covered hundreds or thousands of miles. Valuable materials such as flint, obsidian, and seashells made their way long distances from where they were gathered. Ritual groups such as North American clans and Australian ‘skins’ could knit together huge areas with shared traditions of hospitality and kinship. In some places, annual animal migrations brought together large groups of people for short periods of time into gigantic hunts or harvest festivals. Rituals, marriages and feasts were typical accompaniments to the butchering, cooking and preserving of the hunted animals.

The Emergence of Agriculture

Sedentary Foragers

While human foragers inhabited a wide variety of environments, from river deltas to tropical rain-forests to sub-arctic taiga, not every ecosystem is equally abundant for human needs. Many foraging cultures were very mobile, following animal herds or rotating from area to area at different seasons. But in places such as southern Japan, the west coast of North America, and parts of southwest Asia, the local game and edible plants were so abundant there was little need for the locals to travel. Sedentary foraging settlements developed. Sedentary living allowed these foraging cultures to develop in new ways. The people living in these small towns owned more possessions than nomads, since they didn’t have to carry what they owned from place to place. They could build large, permanent homes, create food storage pits, develop pottery, and engage in ‘gardening’ — protecting and planting local wild foods in convenient locations. Accumulated possessions could be passed on to children and form the basis for inherited differences in status and power, although in many such cases egalitarian institutions persisted. Some sedentary foragers, such as the Natufian culture of the ancient Levant, developed specialized technologies such as sickles and grindstones to exploit and process the seeds of wild grasses such as wheat, barley or rye.

The Natufian culture is often-called ‘proto-agricultural’, since they lived in ways that are reminiscent of farmers, but without planting domesticated crops. Instead they gathered the wild ancestors of what would later become domesticated species. They may have been the first people to bake bread and brew beer –certainly the earliest evidence for either of these foods is found at Natufian sites. They lived in semi-forested land where wild wheat naturally grew, and built large villages with round houses that were partly underground, so that their floors were several feet lower than the outside. While wheat was an important food, they also hunted gazelles and boars, fished in local rivers with bone fishhooks, and gathered wild pistachios and almonds. They made jewellery using animal teeth and shells, carved small sculptures out of stone (including one depicting a couple having sex), and buried some of their dead with abundant grave goods, including grindstones and tortoiseshell bowls. Their culture lasted for about three and a half thousand years — nearly as long as recorded history, and much longer than any of the famous empires and civilizations that we will discuss in subsequent chapters. Because we know of them only from archeology, however, we are left with many questions about their beliefs, their social structure, and the process by which they moved towards agriculture.

Early farming

In an extremely slow process that operated over thousands of years, some sedentary foragers such as the Natufians began to rely increasingly on planting and growing wild crops, which gradually transformed the wild crops into domesticated varieties. For the descendants of the Natufians, the emergence of agriculture may have been caused by repeated climate change that affected the availability of wild cereals, forcing the culture to adapt or perish. A major advantage of planting and tending crops was that it could produce much more food from the same area of land. It is impossible to overstate how important these changes were. The very basis of human life is how much energy we can derive from food; with agriculture and animal domestication, it was possible for families to grow much larger and overall population levels to rise dramatically.

A disadvantage was farming involved more work than foraging, and the diet was less varied and nutritious. Foragers had more leisure time than farmers did, and were also healthier and longer-lived. In many times and places there have been groups of people who remained foragers despite knowing about agriculture, and it is quite possible they did that because they saw no particular advantage in adopting agriculture. There were also many areas that practiced both farming and foraging – right up until the modern era, many farmers also foraged in areas of semi-wilderness near their farms.

Agriculture developed independently in at least six different places: southwest Asia, east Asia, New Guinea, the Andes, Central America, and southeastern North America. From each of these origins, farmers and their crops spread out across suitable land. Cultivating crops eventually led to domesticating animals, including cattle, sheep, goats, donkeys and horses in Eurasia and llamas and alpacas in the Andes. These animals provided valuable meat, could fertilize fields with manure, and served as beasts of burden. They also brought with them epidemic diseases that jumped the species barrier to infect humans who, for the first time, had begun to live in dense settlements suitable to disease transmission. The domestication of food animals also allowed a third major human lifeway to evolve: pastoralism. Pastoralists survive by keeping herds of domesticated animals, subsisting on their meat and milk. Over time, farming and pastoralism spread and replaced foraging in most places. Farming and pastoralism spread partly by replacing the previous populations and partly through cultural transmission. Population growth over time forces farmers to either expand to new land or to intensify their food production. Where the nearby land is suitable for farming and the local foragers are insufficiently numerous or fierce to defend themselves, farmers displace them. In otherwise suitable places whose inhabitants keep the farmers out, population pressure or other motives may eventually induce the locals to adopt farming anyway.

Pastoralism

Pastoralism spreads in areas whose climate is to dry, cold, or otherwise hostile for the locally available crops to thrive. In Eurasia especially, a long stretch of open grassland running from Hungary to Mongolia called the great Eurasian steppe became home to a mosaic of pastoral cultures that herded sheep, cattle, and (eventually) horses. The wealth of pastoralists consists in their herds of animals, and this fact deeply influences pastoral society. Protected and moved to rich grasslands at the right time, a flock can grow rapidly. Ravaged by wolves, poor grazing, or bad weather, a family’s wealth can quickly be lost. But pastoral nomads must especially be wary of theft — cattle rustling, horse thieving, and so forth. Stealing animals is an incredible opportunity, especially for poor young men looking to advance in society. It blends into warfare, as attempts to steal livestock are usually directed against hostile groups, and the animals are defended with violence.

Herding cultures tend to be patriarchal, as men are primarily responsible for protecting their animals and acquiring more through raiding. Kinship and tribal bonds are used to rally together groups of men to defend, recover, or seize the herds of the others. These social bonds among pastoral men therefore become extremely important in these societies: it is their brothers, cousins and childhood friends who are the vital allies they call on in the most dangerous times. The need to intimidate enemies and impress friends and allies can lead to a culture where men ‘defend their honor’ by reacting to insults to themselves or threats to their property with violent revenge. The honor and reputation of the men in the pastoral family is connected to their ability to defend the family and its possessions, including the women and livestock, but also to other expectations such as honesty, helping relatives, offering hospitality, and keeping promises, depending on the culture.

The women of the family may be treated as male possessions whose ownership is in masculine hands. The family women must be protected from raids and are traded in marriage with other families. Wife-stealing in various forms is common in pastoral cultures — sometimes as a ritual involving mutual consent, but sometimes as outright forcible abduction. Regardless of how marriages occur, the wife almost always goes to live with the husband’s family — a practice known as patrilocal family structure. This allows the men to maintain their childhood and family bonds, but uproots women from their childhood homes and social connections. These tendencies of pastoral societies should not be overdrawn: women were not treated like slaves, and often had important social and ritual roles — negotiating, offering advice, and sometimes leading. Pastoral women often lived with a great deal of freedom and took on significant power and responsibilities, travelling long distances and leading the household, particularly when the men were away in warfare or hunting.

Pastoralists generally rely on neighbouring farmers for food, tools and luxury goods that they cannot produce themselves. Depending on the circumstances, this can be via trade, tribute, or raiding. Archaeologists find consistent evidence of coins and tools that travel long distance from settled lands into pastoral areas. When relations between pastoralists and their farming neighbours are peaceful, pastoralists integrate themselves into a mixed, interdependent economy by providing the milk, meat or wool that their herds provide in abundance. When their neighbours are vulnerable, the pastoralists may become predatory, threatening violence to extract regular payments, or aggressively stealing what they want. This became much more dangerous and prevalent after the development of chariots and, later, horseback riding. As we shall see, the nomadic pastoralists in the dry lands outside the boundaries of civilization often intrude dramatically into the written histories of their city-dwelling neighbours. Groups such as the Persians, Huns, Arabs, Turks and Mongols would use their masterful horsemanship to conquer neighbouring farmers and establish aristocratic warrior dynasties to rule them. But these empires will emerge much later, after cities develop and civilization emerges.

Early farming: Çatalhöyük

Of the areas in which agriculture developed, the Fertile Crescent enjoyed significant advantages, perhaps explaining why it was the earliest cradle of farming. Many nutritious staple crops like wheat and barley grew naturally in the region. Several of the key animal species that were first domesticated by humans were also native, including goats, sheep, and cows. The region was also much more temperate and fertile than it is today, and the transition from hunting and gathering to large-scale farming was possible in Mesopotamia in a way that it was not in most other regions of the ancient world.

The food surplus that agriculture made possible in the Fertile Crescent eventually led to the emergence of the first large settlements. Some of the earliest that were large enough to quality as towns or even small cities were Jericho in Palestine, which existed by about 8000 BCE, and Çatal Höyük in Turkey, which existed by about 7500 BCE. There may have been others in the Fertile Crescent, but due to their antiquity the remains of only a few have survived to be studied by archaeologists.

Çatalhöyük was built on a plain near a river in southern Anatolia. It is made of hundreds of houses built in a dense interconnected mass, with no interior streets or spaces. The houses are mostly entered from the roof via ladders or steep stairs, and the whole settlement is like one gigantic subdivided building. One obvious effect of the unique construction is that each site acts like a fortress. The outer wall has no gates or entrances and to enter any building one must climb up onto the rooftops.

Each house-room was used by an extended family, containing its own hearth and numerous art or religious objects, most notably wild cattle skulls that were painted and mounted on the walls. The rooms were plastered and painted with elaborate scenes, and the profusion of sculptures and art objects suggests a rich symbolic and spiritual life for the villagers. A family buried their ancestors beneath the hearth in their house, and one distinctive practice was that some ancestral skulls were detached from the body, covered with plaster, and painted with faces.

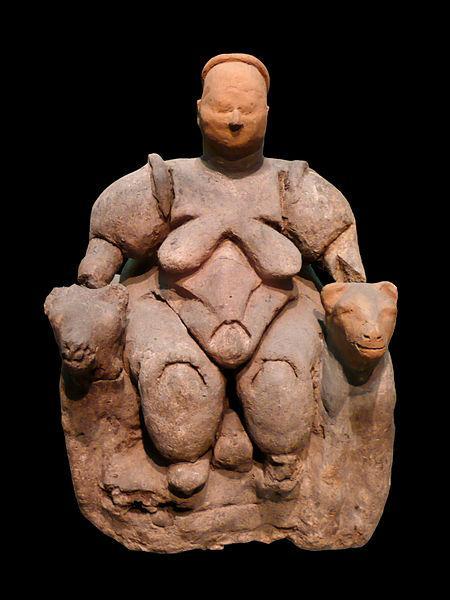

1.5 An example of a “Venus figurine” excavated at Çatalhöyük.

The first excavator of the site argued that the religion of Çatalhöyük was based around worship of a mother goddess, based on the many female sculptures found there, such as the one shown above. Her enthroned position certainly suggests some kind of authority, but it is difficult to reconstruct with any certainty the details of their beliefs from archaeology. Detailed understanding of ancient belief systems becomes possible when we can read what people wrote about themselves, some four thousand years later in Sumer and Egypt.

There are few indications of social hierarchy or leadership roles at Çatalhöyük. There seem to have been richer and poorer inhabitants, but we see no large temples or palaces, and no buildings that are clearly for public use. It is a town made up of very similarly-sized houses and whatever government it might have had left few traces in its architecture. When, in later societies, we find hereditary chiefs and kings, they usually bolster their authority with obvious displays of their superiority — large houses, monuments, special items displaying their power. The lack of that at Çatalhöyük suggests an egalitarian community where people were socially equal, or nearly so. However, it was during its height one of the largest human communities that had ever existed, with up to 10,000 inhabitants in its eastern site. A community of that size is likely to have developed institutions to co-ordinate group activities and resolve disputes, but what those were has been lost to time.

The foundation of Çatalhöyük’s prosperity was its fertile fields filled with yellow wheat and barley. This early agriculture was supplemented by hunting of local game such as wild cattle and deer, and gathering local fruits and nuts. The productivity of their environment probably allowed some of the population to specialize, producing finely crafted tools and the rich diversity of artistic objects which are found at the site. Çatalhöyük imported obsidian from nearby places, and obsidian tools produced at Çatalhöyük have been discovered by archaeologists hundreds of miles away. This indicates Çatalhöyük was part of larger trade networks and may have been a centre of craft production, as many later towns and cities were. Weaving was also used to produce clothing, rope, baskets and mats, using fibres made from oak bark. The prevalence of crafts and trade might explain the variation of wealth that has been observed in the funerals of the inhabitants: trade and craft industries have been known to create wealth disparities in other cultures.

The emergence of patriarchy

While Çatalhöyük seems to have had relative gender equality and may have had special religious roles for women, over time farming life in most places seems to have led to the gradual emergence of patriarchy. As we shall see, by the time that writing develops in Sumer and Egypt, political power is held in male hands and men and women are systematically unequal. Since this transition takes place before the development of writing, the process by which it happened remains unclear. Many authors have discussed the causes of the emergence of patriarchy in farming communities, and there is no definitive evidence to settle the disputes. Without insisting on the central role of any particular explanation, we will consider two factors that may have contributed to this development.

Women in farming communities bore more children then foragers, partly because they tended to stop breastfeeding their children earlier, which led to more frequent pregnancies. This was partly made possible by the sedentary farming life, meaning young children did not have to be carried from place to place. It was also made necessary by the rise of epidemic diseases that accompanied sedentary living and animal domestication. Children were especially vulnerable to disease, and it became common for a quarter to a half of children to die before adulthood. Women in farming communities spent more time pregnant, gave birth more frequently and needed to spend more time caring for children then foragers did. More child-care responsibilities may have led to smaller roles in other areas of the community.

The emergence of sedentary living is also connected to the growth of organized aggression and, eventually, large scale warfare. Farming produced stores of food and valuables that could be seized by neighbours, and the control of or access to land itself was also a common source of conflict. Both Çatalhöyük and Jericho, the two earliest farming towns we know of, were fortified against attack: Jericho with a large wall and tower, Çatalhöyük by its fortress-like system of interconnected houses. By the time we have written records, political power was closely tied to two sources of authority: religious status and military leadership. Religious status was not consistently gendered, and high status priestesses and feminine shamans are attested in many different cultures. But military leadership was overwhelmingly a masculine role, because of the widespread masculine gendering of fighting and violent conflict that we have discussed. Leadership is important in any kind of organised conflict, and this importance increases as the fighting forces get larger. The more important fighting wars and winning battles is to a given culture, the more that war leaders will be valued and honoured and the more power tends to be concentrated in their hands. This is further enhanced by the fact that victorious wars can lead to huge rewards for the winners, including wealth, land, slaves, and status. Cultures that commonly engage in warfare will therefore tend to disproportionately put power in men’s hands and move in patriarchal directions.

Whatever the causes, the growth of patriarchy caused by farming has to be counted as one of its most transformative effects. The spread of agriculture is accompanied by a gradual transformation of social systems that put women in subordinate statuses and exclude them from political power as it develops. This in some cultures develops into views about the inherent inferiority of women, leading to consequences such as female infanticide, exploitation, and very restricted life choices for many women. We will see the specific forms that patriarchy takes in different civilizations throughout the rest of our history.

This chapter is partly adapted from Western Civilization: A Concise History by Christopher Brooks and is used under a CC BY-NC-SA license.

It contains material from World History: Cultures, States and Societies to 1500 by Berger et. Al. and is used under a CC BY-SA license.

Media Attributions

1.1 Homo Erectus Footprints by Kevin G Hatala, CC BY 4.0

1.2 Human Expansion Map by Dbachmann, CC BY-SA 4.0

1.3 Lascaux Painting by Prof saxx, CC BY-SA 3.0

1.4 Fertile Crescent Map by NormanEinstein, CC BY-SA 3.0

1.5 Venus Figurine by Nevit Dilmen, CC BY-SA 3.0

1.6 Catalhoyuk Room by Elilecht, CC BY-SA 3.0

Feedback/Errata