4-5 Planning Knowledge Translation and Dissemination Activities

Teresa Chan and Siraj Mithoowani

Overview

As with all applied sciences, our work as researchers is not done until the science we conduct is applied by the practitioners in our field. In health professions education research, this means that our frontline faculty who are teaching learners, designing assessments systems, improving curriculae, and leading programs need to be aware of the findings from our scholarship.

For those of you who are unfamiliar with the term Knowledge Translation (KT), it is a term that is used by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR) to describe the activities that take research and translate it into products that ultimately help improve the health of Canadians.

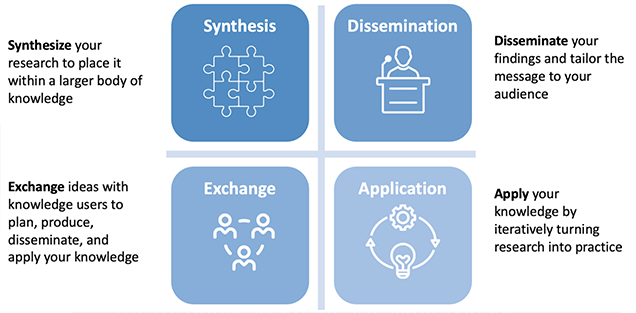

Examples of KT activities are:

- Knowledge synthesis;

- Dissemination;

- Application.

In this chapter you will explore what KT might look like for you and your project(s).

Key Points of the Chapter

In this chapter, participants will:

- Compare and contrast knowledge translation and education.

- Identify linkages and commonalities between knowledge translation, education, and other fields.

- Name at least one new knowledge translation technique that they might apply to their practice.

Vignette

Nikhil was a junior health professions education scholar who had completed his research project on a curricular innovation within his residency program. He had just received a notification from the journal that his article had been accepted for publication!

Ecstatic, he emailed his mentor and the principal investigator for the project… She texted back the following:

Nikhil took a quick breath. He had thought he was DONE, but now he had to do… what was that term again? Knowledge translation?

Through a quick internet search he found out that knowledge translation is when scientists disseminate their study’s findings and/or help others apply them in the real world.

He pondered his project. What would knowledge translation look like for this particular HPE project? What were things he could do to help people become aware of this paper? What could he do to help them better understand the findings and take-home points? And finally, could he find a way to make it easy for others to apply the findings of his study in their own contexts?

Deeper Dive into the Concept

Just like in other applied scientific sectors, the field of health professions education has a KT problem. In a video featuring Dr. Teresa Chan (See below video entitled Social Media and the 21st-Century Scholar), learn about how we can integrate new strategies about KT broadly. In the video she highlights some personal experiences she has in applying novel techniques to translate the knowledge from her own research.

The transfer of research findings into practice is often slow, haphazard and incomplete. Dr. Aliki Thomas’ MERIT rounds video (entitled “Leveraging Knowledge Translation”) describes this phenomenon and takes us through her perspective on how we might close the gap between knowing and doing.

Knowing vs. Doing

The knowing-doing gap has long been acknowledged in many fields (1). What is most interesting within health professions education is that often our researchers are also excellent teachers themselves. So many health professions education researchers already have the necessary skill set to disseminate their research in interesting ways, engage their audience, and teach others how to adapt and to implement their research findings. As Dr. Thomas discusses in her presentation, KT is an active process of “making it happen” rather than “letting it happen”. KT means tailoring research findings and their presentation to specific and relevant audiences to increase uptake and bridge the knowing-doing gap (2).

That being said, many can feel a bit embarrassed about KT efforts, worried about seeming like they’re bragging about their work if they engage in social media-based dissemination (3). Still others may not think about how best to teach or communicate their research, feeling simply exhausted at the end of their hard work to get the project published. Table 4.5.1 below summarizes some knowledge user groups in health professions education research.

| Potential Knowledge User | Examples of end-of-grant KT | Examples of integrated KT |

| Clinical Teachers | Creating an infographic that summarizes your study findings – and then tweeting or publishing these so others can share, download, print, and post. | Consulting clinical teachers about common problems they have to determine and/or refine your research question about a clinical learning environment. |

| Students and trainees | Creating a workshop to present at conferences targeting trainee development around your topic. | Co-creating a podcast with trainees to highlight their stories and help them understand how the content applies to their context. |

| Educational administrators and policymakers | Disseminating a policy paper, end-of-grant report, or engaging in speaking engagements for educational administrators and policymakers. | Consulting these individuals during study design to refine processes or knowledge elicitation tools (e.g. surveys) |

| Educational organizations (e.g. Royal College of Physicians and Surgeons of Canada, College of Family Physicians of Canada, Resident Doctors of Canada) | Reaching out to professional organizations to promote your work on their magazines, podcasts, and blogs. Often these groups are hungry for relevant content, so this may be a great way to let people know you have work that is relevant to their membership. | Engaging in audit of practices aligned with the needs of educational organizations. |

| Institutions (e.g. universities, teaching hospitals, clinics) | Sending copies of your paper with a short summary to key influencers or educational leadership within your institution. | Involving institutional leaders as key stakeholders for piloting a focus group or interview guide to ensure that the data collected will be relevant to institutional needs. |

| Whole Communities | Creating a public social media campaign that explains your research findings and how they can benefit communities. | Involving community members in determining the research question to ensure that it resonates with their needs. |

Frameworks for knowledge translation

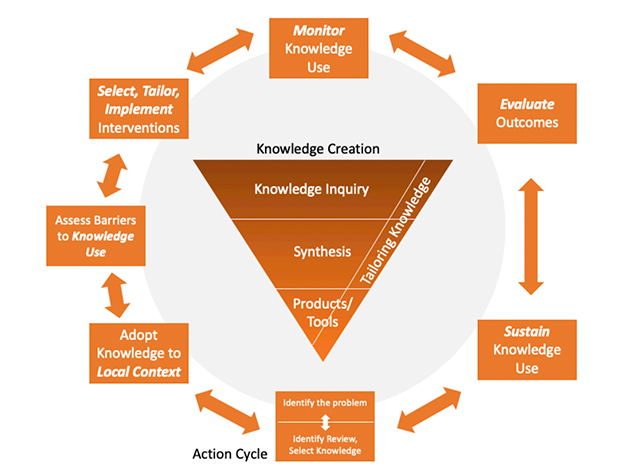

In the videos above, Drs. Chan and Thomas review several conceptual frameworks for knowledge translation, including the Knowledge to Action cycle (4), Pathman’s pipeline (5) and the Theoretical Domains framework (6). Here we will use a worked example to illustrate the Knowledge to Action (KTA) cycle (4).

Graham et al. (4) conceptualize the KTA cycle as a funnel of knowledge creation surrounded by an action cycle that facilitates uptake and application of that knowledge, as shown in Figure 4.5.1. Arrows are bidirectional suggesting that this is an iterative process and there may be feedback between the phases. Knowledge Inquiry sits at the top of the knowledge creation funnel. This represents unfiltered information of variable quality that is not ready for “prime time”. Moving down the funnel, knowledge is sequentially refined and aggregated – first in the form of syntheses (e.g. meta-analyses) and then as end-user tools (e.g. checklists and guidelines). The action cycle begins by identifying a problem and selecting (and appraising) the appropriate knowledge to apply.

Generic knowledge is tailored to the local context, barriers to knowledge translation are analyzed, and interventions are planned that mitigate those barriers. The use of knowledge by end-users is evaluated along with any relevant educational or clinical outcomes (e.g. pass/fail rates for licensing exams). Finally, the cycle starts anew with a view toward sustaining and refining knowledge use.

Take for example the implementation of Competency by Design (CBD). CBD is a knowledge product co-developed by the Royal College of Physicians and Surgeons of Canada and its stakeholders that is rooted in educational theory including outcomes-based education, whole task learning and programmatic assessment. To implement CBD at the residency program level means moving through the Action Cycle.

- First, educational problems must be identified that justify the curriculum change; e.g. the lack of emphasis on direct observation and feedback in traditional residency programs.

- Implementation must then be adapted to the local context; e.g. programming assessment forms into MedSIS, which is the learning analytics platform in use by McMaster University.

- Barriers to knowledge use should be identified. In the case of CBD, faculty members might feel they lack sufficient time or knowledge to conduct regular direct observation and feedback in a busy clinical setting.

- Interventions should be designed to mitigate barriers, e.g. planning faculty development sessions, simplifying the process of documenting feedback through the use of checklists or software.

- Knowledge use can be monitored and evaluated by cross-sectional surveys and focus groups consisting of faculty and learners. Educational outcomes of interest might include pass rates for licensing exams or other tests of performance (e.g. OSCE scores).

- Continuous evaluation of CBD processes and outcomes is required to sustain knowledge use.

The following summary diagram (Figure 4.5.2) can be a useful guide for those getting started in knowledge translation of their work for the first time.

Examples of Knowledge Translation activities within Health Professions Education

The tables below (Box 4.5.1 and 4.5.2) describe two programs of research that has been used by two teams associated with one of our chapter co-authors (Dr. Teresa Chan) and her collaborators.

Box 4.5.1: The METRIQ study team

Research programme:

Measuring the impact and quality of social media educational resources.

Papers to be translated:

The METRIQ study research collaborative has published nearly 30 studies as a team about measuring impact and quality of online resources. They have a website that details their team, assists them with recruiting for their latest studies, and houses all of their research in a one stop shop.

Knowledge Synthesis Activities:

a) Rapid Review

Ting DK, Boreskie P, Luckett-Gatopoulos S, Gysel L, Lanktree MB, Chan TM. Quality appraisal and assurance techniques for free open access medical education (FOAM) resources: a rapid review. InSeminars in nephrology 2020 May 1 (Vol. 40, No. 3, pp. 309-319). WB Saunders. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0270929520300528b

b) Guideline Creation:

Members of this team have worked on a consensus guideline for applying this research to the Promotion & Tenure process: Husain A, Repanshek Z, Singh M, Ankel F, Beck-Esmay J, Cabrera D, Chan TM, Cooney R, Gisondi M, Gottlieb M, Khadpe J. Consensus guidelines for digital scholarship in academic promotion. Western Journal of Emergency Medicine. 2020 Jul;21(4):883. doi: 10.5811/westjem.2020.4.46441

Dissemination:

a) Website:

This team has both a website (which lists their teammates and their research papers) and a Twitter account that they use for recruitment AND dissemination.

Website: https://metriqstudy.org/research-agenda

b) Twitter Account: @METRIQstudy

This account assists with tweeting about their research and also helps with recruiting for their latest study.

You can read about these techniques in one of their methods papers:

Thoma B, Paddock M, Purdy E, Sherbino J, Milne WK, Siemens M, Petrusa E, Chan T. Leveraging a virtual community of practice to participate in a survey‐based study: a description of the METRIQ study methodology. AEM education and training. 2017 Apr;1(2):110-3. https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1002/aet2.10013

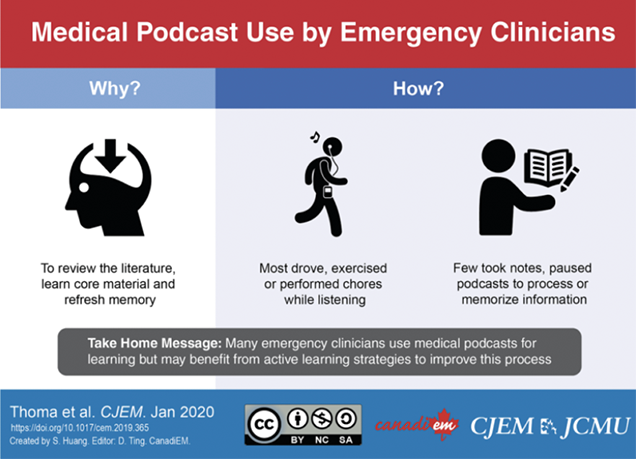

c) Infographic Creation about their Articles:

Thoma B, Goerzen S, Horeczko T, Roland D, Tagg A, Chan TM, Bruijns S, Riddell J, METRIQ Podcast Study Collaborators. An international, interprofessional investigation of the self-reported podcast listening habits of emergency clinicians: A METRIQ Study. Canadian Journal of Emergency Medicine. 2020 Jan;22(1):112-7. https://doi.org/10.1017/cem.2019.427

Example Infographic:

Application:

Application:

This team has engaged in a quality improvement cycle to make their critical appraisal tools more useful and into usable infographics and formats to help frontline teachers and trainees to determine the quality of online educational resources.

a) Revised METRIQ Score – Based on end-user feedback, this scoring tool was refined and simplified. For ease of use and adoption, a visually-appealing scoring rubric was created for this revision and can be found within the paper.

Paper & link: Colmers-Gray IN, Krishnan K, Chan TM, Trueger NS, Paddock M, Grock A, Zaver F, Thoma B. The revised METRIQ score: a quality evaluation tool for online educational resources. AEM education and training. 2019 Oct;3(4):387-92. https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1002/aet2.10376

b) Revised AIR Score – Same as above, the AIR score which was previously studied by the group was also revised and redesigned with a new user-friendly rubric.

Paper & link: Grock A, Jordan J, Zaver F, Colmers‐Gray IN, Krishnan K, Chan T, Thoma B, Alexander C, Alkhalifah M, Almehlisi AS, Alqahtani S. The revised Approved Instructional Resources score: An improved quality evaluation tool for online educational resources. AEM Education and Training. 2021 May 16:e10601. https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1002/aet2.10601

c) Systematic Review of Open Access Educational Resources – The above tools enabled members of the METRIQ team to engage in a first-of-its-kind systematic review of open access resources. The scoring tool was used as a quality filter for the resources to identify high-quality resources for teachers to use in their curriculae.

Paper & link: Grock A, Bhalerao A, Chan TM, Thoma B, Wescott AB, Trueger NS. Systematic Online Academic Resource (SOAR) review: renal and genitourinary. AEM education and training. 2019 Oct;3(4):375-86. https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1002/aet2.10351

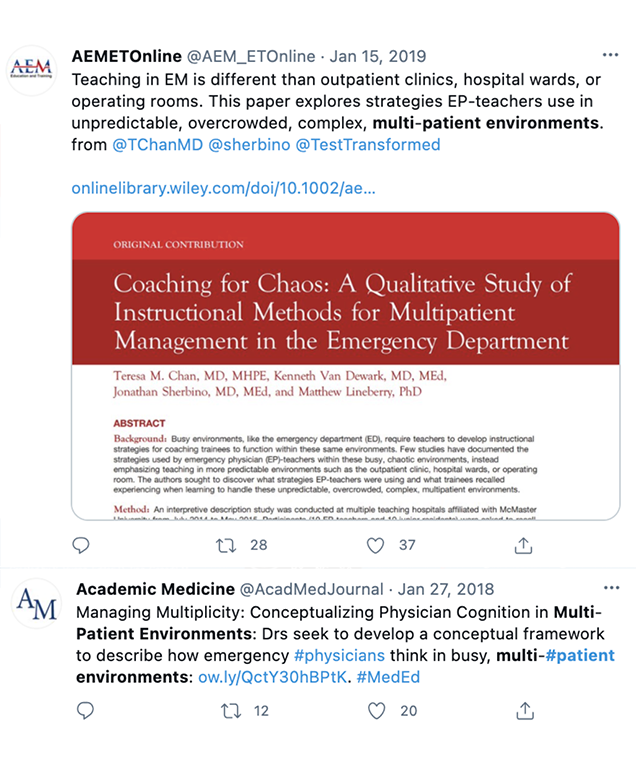

Box 4.5.2: Multipatient Environments & the GridlockED game

Research programme:

Clinical care and diagnostic reasoning within multipatient environment settings.

Papers to be translated:

This group had three main papers that were part of a small programme of research that became the fodder for knowledge translation.

- Chan, T.M., Van Dewark, K., Sherbino, J., Schwartz, A., Norman, G. and Lineberry, M., 2017. Failure to flow: An exploration of learning and teaching in busy, multi-patient environments using an interpretive description method. Perspectives on medical education, 6(6), pp.380-387.

- Chan TM, Mercuri M, Van Dewark K, Sherbino J, Schwartz A, Norman G, Lineberry M. Managing multiplicity: conceptualizing physician cognition in multipatient environments. Academic Medicine. 2018 May 1;93(5):786-93.

- Chan, T.M., Van Dewark, K., Sherbino, J. and Lineberry, M., 2019. Coaching for chaos: a qualitative study of instructional methods for multipatient management in the emergency department. AEM education and training, 3(2), pp.145-155.

Knowledge Synthesis Activities:

This team has engaged in a few different knowledge syntheses:

a) Blog posts summarizing their program of research

b) A blog post that summarizes key findings from the papers into a more user-friendly read for frontline practitioners (teachers and students)

c) A summary paper for a national journal about the key take-home points for frontline teachers to use when teaching about multipatient environments: Chan TM, Sherbino J, Welsher A, Chorley A, Pardhan A. Just the Facts: how to teach emergency department flow management. Canadian Journal of Emergency Medicine. 2020 Jul;22(4):459-62. https://doi.org/10.1017/cem.2020.32

Dissemination:

The authorship team has linked up with the publishing journals to generate tweets to highlight the work when it was finally published.

Application:

Application:

This program of research spurred on the creation of a serious game entitled GridlockED (gridlockedgame.com). It allows for teachers and/or trainees to engage with the concepts of multi-patient environments in a safe, low-stakes environment (e.g. a board game).

Interestingly, the creation of this game also triggered its own follow-up research and scholarship.

- Tsoy D, Sneath P, Rempel J, Huang S, Bodnariuc N, Mercuri M, Pardhan A, Chan TM. Creating GridlockED: A serious game for teaching about multipatient environments. Academic Medicine. 2019 Jan 1;94(1):66-70.

- Brar G, Lambert S, Huang S, Dang R, Chan TM. Using Observation to Determine Teachable Moments Within a Serious Game: A GridlockED as Medical Education (GAME) Study. AEM education and training. 2021 Apr;5(2):e10456.

- Hale SJ, Wakeling S, Bhalerao A, Balakumaran J, Huang S, Mondoux S, Blain JB, Chan TM. Feeling the flow with a serious game workshop: GridlockED as Medical Education 2 study (GAME2 study). AEM Education and Training. 2021 Jul;5(3):e10576.

- Hale SJ, Wakeling S, Blain JB, Pardhan A, Mondoux S, Chan TM. Side effects may include fun: Pre-and post-market surveillance of the GridlockED serious game. Simulation & Gaming. 2020 Jun;51(3):365-77.

Key Takeaways

In summary, when engaging in knowledge translation of health professions education research, we must consider the following:

- Discern and construct a dissemination plan with your target knowledge users in mind – Make sure that you consider those who are your target audience for your study.

- Consider harnessing the power of non-traditional media (e.g. social media, podcasting, blogging) – Most researchers in the health professions do not have access to professionals who can help them generate press releases and newsworthy buzz around their papers. As such, it is useful to create your own buzz. Consider using non-traditional media such as social media (e.g. Twitter, Instagram), podcasting, or blogging to get the word out. Funny enough, sometimes your social media content will generate the biggest buzz.

- Make application easy – If you have a new finding that should change practice try to find a way to make things easy. Consider creating infographics, checklists or other tools. Consider the “outer ring” of the Knowledge-to-action cycle and think through how you might create knowledge products or tools that help frontline knowledge users to engage with your new knowledge.

Vignette Conclusion

Nikhil paused to reflect on his KT plan and comes to realized that there was a lot of work ahead to turn research into action. He considered his target knowledge users: what would residents and faculty members want to know about his innovation?

Nikhil began synthesizing his work in a series of blog posts for professional societies within his specialty and worked with a team of medical students to develop easy-to-digest infographics that conveyed the paper’s key points. He used Twitter to craft a ‘tweetorial ‘ on his key findings and tagged his co-authors, key influencers within health professions education research, and the journal that published his paper to start a buzz about his recent research paper. Finally, he met with his mentor and Program Director to create a strategy for local implementation. His mentor reminded him that he would need to adapt his research findings to fit their institution’s needs and available resources.

References

- Pfeffer J, Sutton RI. The knowing-doing gap: How smart companies turn knowledge into action. Harvard business press; 2000.

- Thomas A, Bussières A. Knowledge translation and implementation science in health professions education: time for clarity?. Academic Medicine. 2016 Dec 1;91(12):e20. https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0000000000001396

- Lu D, Ruan B, Lee M, Yilmaz Y, Chan TM. Good practices in harnessing social media for scholarly discourse, knowledge translation, and education. Perspectives on medical education. 2021 Jan;10(1):23-32. https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s40037-020-00613-0

- Graham ID, Logan J, Harrison MB, Straus SE, Tetroe J, Caswell W, Robinson N. Lost in knowledge translation: time for a map?. Journal of continuing education in the health professions. 2006 Dec;26(1):13-24. https://eric.ed.gov/?id=EJ759233

- Diner BM, Carpenter CR, O’Connell T, Pang P, Brown MD, Seupaul RA, Celentano JJ, Mayer D, KT-CC Theme IIIa Members. Graduate medical education and knowledge translation: role models, information pipelines, and practice change thresholds. Academic Emergency Medicine. 2007 Nov;14(11):1008-14. https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1111/j.1553-2712.2007.tb02381.x

- Cane J, O’Connor D, Michie S. Validation of the theoretical domains framework for use in behaviour change and implementation research. Implementation science. 2012 Dec;7(1):1-7. https://link.springer.com/article/10.1186/1748-5908-7-37

- Ting, D.K., Boreskie, P., Luckett-Gatopoulos, S., Gysel, L., Lanktree, M.B. and Chan, T.M., 2020, May. Quality Appraisal and Assurance Techniques for Free Open Access Medical Education (FOAM) Resources: A Rapid Review. Seminars in nephrology (Vol. 40, No. 3, pp. 309-319). WB Saunders. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0270929520300528

- Husain A, Repanshek Z, Singh M, Ankel F, Beck-Esmay J, Cabrera D, Chan TM, Cooney R, Gisondi M, Gottlieb M, Khadpe J. Consensus guidelines for digital scholarship in academic promotion. Western Journal of Emergency Medicine. 2020 Jul;21(4):883. doi: 10.5811/westjem.2020.4.46441

- Thoma B, Paddock M, Purdy E, Sherbino J, Milne WK, Siemens M, Petrusa E, Chan T. Leveraging a virtual community of practice to participate in a survey‐based study: a description of the METRIQ study methodology. AEM education and training. 2017 Apr;1(2):110-3. https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1002/aet2.10013

- Thoma B, Goerzen S, Horeczko T, Roland D, Tagg A, Chan TM, Bruijns S, Riddell J, METRIQ Podcast Study Collaborators. An international, interprofessional investigation of the self-reported podcast listening habits of emergency clinicians: A METRIQ Study. Canadian Journal of Emergency Medicine. 2020 Jan;22(1):112-7. https://doi.org/10.1017/cem.2019.427

- Chan, T.M., Van Dewark, K., Sherbino, J., Schwartz, A., Norman, G. and Lineberry, M., 2017. Failure to flow: An exploration of learning and teaching in busy, multi-patient environments using an interpretive description method. Perspectives on medical education, 6(6), pp.380-387. https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s40037-017-0384-7

- Chan TM, Mercuri M, Van Dewark K, Sherbino J, Schwartz A, Norman G, Lineberry M. Managing multiplicity: conceptualizing physician cognition in multipatient environments. Academic Medicine. 2018 May 1;93(5):786-93. https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0000000000002081

- Chan, T.M., Van Dewark, K., Sherbino, J. and Lineberry, M., 2019. Coaching for chaos: a qualitative study of instructional methods for multipatient management in the emergency department. AEM education and training, 3(2), pp.145-155. https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1002/aet2.10312

- Chan TM, Sherbino J, Welsher A, Chorley A, Pardhan A. Just the Facts: how to teach emergency department flow management. Canadian Journal of Emergency Medicine. 2020 Jul;22(4):459-62. https://doi.org/10.1017/cem.2020.32

- Tsoy D, Sneath P, Rempel J, Huang S, Bodnariuc N, Mercuri M, Pardhan A, Chan TM. Creating GridlockED: A serious game for teaching about multipatient environments. Academic Medicine. 2019 Jan 1;94(1):66-70. https://journals.lww.com/academicmedicine/FullText/2019/01000/Creating_GridlockED__A_Serious_Game_for_Teaching.25.aspx

- Brar G, Lambert S, Huang S, Dang R, Chan TM. Using Observation to Determine Teachable Moments Within a Serious Game: A GridlockED as Medical Education (GAME) Study. AEM education and training. 2021 Apr;5(2):e10456. https://doi.org/10.1002/aet2.10456

- Hale SJ, Wakeling S, Bhalerao A, Balakumaran J, Huang S, Mondoux S, Blain JB, Chan TM. Feeling the flow with a serious game workshop: GridlockED as Medical Education 2 study (GAME2 study). AEM Education and Training. 2021 Jul;5(3):e10576. https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1002/aet2.10576

- Hale SJ, Wakeling S, Blain JB, Pardhan A, Mondoux S, Chan TM. Side effects may include fun: Pre-and post-market surveillance of the GridlockED serious game. Simulation & Gaming. 2020 Jun;51(3):365-77. https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/full/10.1177/1046878120904125