Learning Objectives

By the end of this section, you will be able to:

- List the role of the six most important electrolytes in the body

- Name the disorders associated with abnormally high and low levels of the six electrolytes

- Identify the predominant extracellular anion

- Describe the role of aldosterone on the level of water in the body

The body contains a large variety of ions, or electrolytes, which perform a variety of functions. Some ions assist in the transmission of electrical impulses along cell membranes in neurons and muscles. Other ions help to stabilize protein structures in enzymes. Still others aid in releasing hormones from endocrine glands. All of the ions in plasma contribute to the osmotic balance that controls the movement of water between cells and their environment.

Electrolytes in living systems include sodium, potassium, chloride, bicarbonate, calcium, phosphate, magnesium, copper, zinc, iron, manganese, molybdenum, copper, and chromium. In terms of body functioning, six electrolytes are most important: sodium, potassium, chloride, bicarbonate, calcium, and phosphate.

Roles of Electrolytes

These six ions aid in nerve excitability, endocrine secretion, membrane permeability, buffering body fluids, and controlling the movement of fluids between compartments. These ions enter the body through the digestive tract. More than 90 percent of the calcium and phosphate that enters the body is incorporated into bones and teeth, with bone serving as a mineral reserve for these ions. In the event that calcium and phosphate are needed for other functions, bone tissue can be broken down to supply the blood and other tissues with these minerals. Phosphate is a normal constituent of nucleic acids; hence, blood levels of phosphate will increase whenever nucleic acids are broken down.

Excretion of ions occurs mainly through the kidneys, with lesser amounts lost in sweat and in feces. Excessive sweating may cause a significant loss, especially of sodium and chloride. Severe vomiting or diarrhea will cause a loss of chloride and bicarbonate ions. Adjustments in respiratory and renal functions allow the body to regulate the levels of these ions in the ECF.

Table 26.1 lists the reference values for blood plasma, cerebrospinal fluid (CSF), and urine for the six ions addressed in this section. In a clinical setting, sodium, potassium, and chloride are typically analyzed in a routine urine sample. In contrast, calcium and phosphate analysis requires a collection of urine across a 24-hour period, because the output of these ions can vary considerably over the course of a day. Urine values reflect the rates of excretion of these ions. Bicarbonate is the one ion that is not normally excreted in urine; instead, it is conserved by the kidneys for use in the body’s buffering systems.

| Electrolyte and Ion Reference Values (Table 26.1) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Name | Chemical symbol | Plasma | CSF | Urine |

| Sodium | Na+ | 136.00–146.00 (mM) | 138.00–150.00 (mM) | 40.00–220.00 (mM) |

| Potassium | K+ | 3.50–5.00 (mM) | 0.35–3.5 (mM) | 25.00–125.00 (mM) |

| Chloride | Cl– | 98.00–107.00 (mM) | 118.00–132.00 (mM) | 110.00–250.00 (mM) |

| Bicarbonate | HCO3– | 22.00–29.00 (mM) | —— | —— |

| Calcium | Ca++ | 2.15–2.55 (mmol/day) | —— | Up to 7.49 (mmol/day) |

| Phosphate | HPO42−HPO42− | 0.81–1.45 (mmol/day) | —— | 12.90–42.00 (mmol/day) |

Sodium

Sodium is the major cation of the extracellular fluid. It is responsible for one-half of the osmotic pressure gradient that exists between the interior of cells and their surrounding environment. People eating a typical Western diet, which is very high in NaCl, routinely take in 130 to 160 mmol/day of sodium, but humans require only 1 to 2 mmol/day. This excess sodium appears to be a major factor in hypertension (high blood pressure) in some people. Excretion of sodium is accomplished primarily by the kidneys. Sodium is freely filtered through the glomerular capillaries of the kidneys, and although much of the filtered sodium is reabsorbed in the proximal convoluted tubule, some remains in the filtrate and urine, and is normally excreted.

Hyponatremia is a lower-than-normal concentration of sodium, usually associated with excess water accumulation in the body, which dilutes the sodium. An absolute loss of sodium may be due to a decreased intake of the ion coupled with its continual excretion in the urine. An abnormal loss of sodium from the body can result from several conditions, including excessive sweating, vomiting, or diarrhea; the use of diuretics; excessive production of urine, which can occur in diabetes; and acidosis, either metabolic acidosis or diabetic ketoacidosis.

A relative decrease in blood sodium can occur because of an imbalance of sodium in one of the body’s other fluid compartments, like IF, or from a dilution of sodium due to water retention related to edema or congestive heart failure. At the cellular level, hyponatremia results in increased entry of water into cells by osmosis, because the concentration of solutes within the cell exceeds the concentration of solutes in the now-diluted ECF. The excess water causes swelling of the cells; the swelling of red blood cells—decreasing their oxygen-carrying efficiency and making them potentially too large to fit through capillaries—along with the swelling of neurons in the brain can result in brain damage or even death.

Hypernatremia is an abnormal increase of blood sodium. It can result from water loss from the blood, resulting in the hemoconcentration of all blood constituents. This can lead to neuromuscular irritability, convulsions, CNS lethargy, and coma. Hormonal imbalances involving ADH and aldosterone may also result in higher-than-normal sodium values.

Potassium

Potassium is the major intracellular cation. It helps establish the resting membrane potential in neurons and muscle fibers after membrane depolarization and action potentials. In contrast to sodium, potassium has very little effect on osmotic pressure. The low levels of potassium in blood and CSF are due to the sodium-potassium pumps in cell membranes, which maintain the normal potassium concentration gradients between the ICF and ECF. The recommendation for daily intake/consumption of potassium is 4700 mg. Potassium is excreted, both actively and passively, through the renal tubules, especially the distal convoluted tubule and collecting ducts. Potassium participates in the exchange with sodium in the renal tubules under the influence of aldosterone, which also relies on basolateral sodium-potassium pumps.

Hypokalemia is an abnormally low potassium blood level. Similar to the situation with hyponatremia, hypokalemia can occur because of either an absolute reduction of potassium in the body or a relative reduction of potassium in the blood due to the redistribution of potassium. An absolute loss of potassium can arise from decreased intake, frequently related to starvation. It can also come about from vomiting, diarrhea, or alkalosis. Hypokalemia can cause metabolic acidosis, CNS confusion, and cardiac arrhythmias.

Some insulin-dependent diabetic patients experience a relative reduction of potassium in the blood from the redistribution of potassium. When insulin is administered and glucose is taken up by cells, potassium passes through the cell membrane along with glucose, decreasing the amount of potassium in the blood and IF, which can cause hyperpolarization of the cell membranes of neurons, reducing their responses to stimuli.

Hyperkalemia, an elevated potassium blood level, also can impair the function of skeletal muscles, the nervous system, and the heart. Hyperkalemia can result from increased dietary intake of potassium. In such a situation, potassium from the blood ends up in the ECF in abnormally high concentrations. This can result in a partial depolarization (excitation) of the plasma membrane of skeletal muscle fibers, neurons, and cardiac cells of the heart, and can also lead to an inability of cells to repolarize. For the heart, this means that it won’t relax after a contraction, and will effectively “seize” and stop pumping blood, which is fatal within minutes. Because of such effects on the nervous system, a person with hyperkalemia may also exhibit mental confusion, numbness, and weakened respiratory muscles.

Chloride

Chloride is the predominant extracellular anion. Chloride is a major contributor to the osmotic pressure gradient between the ICF and ECF, and plays an important role in maintaining proper hydration. Chloride functions to balance cations in the ECF, maintaining the electrical neutrality of this fluid. The paths of secretion and reabsorption of chloride ions in the renal system follow the paths of sodium ions.

Hypochloremia, or lower-than-normal blood chloride levels, can occur because of defective renal tubular absorption. Vomiting, diarrhea, and metabolic acidosis can also lead to hypochloremia. Hyperchloremia, or higher-than-normal blood chloride levels, can occur due to dehydration, excessive intake of dietary salt (NaCl) or swallowing of sea water, aspirin intoxication, congestive heart failure, and the hereditary, chronic lung disease, cystic fibrosis. In people who have cystic fibrosis, chloride levels in sweat are two to five times those of normal levels, and analysis of sweat is often used in the diagnosis of the disease.

External Website

Watch this video to see an explanation of the effect of seawater on humans. What effect does drinking seawater have on the body?

Bicarbonate

Bicarbonate is the second most abundant anion in the blood. Its principal function is to maintain your body’s acid-base balance by being part of buffer systems. This role will be discussed in a different section.

Bicarbonate ions result from a chemical reaction that starts with carbon dioxide (CO2) and water, two molecules that are produced at the end of aerobic metabolism. Only a small amount of CO2 can be dissolved in body fluids. Thus, over 90 percent of the CO2 is converted into bicarbonate ions, HCO3–, through the following reactions:

The bidirectional arrows indicate that the reactions can go in either direction, depending on the concentrations of the reactants and products. Carbon dioxide is produced in large amounts in tissues that have a high metabolic rate. Carbon dioxide is converted into bicarbonate in the cytoplasm of red blood cells through the action of an enzyme called carbonic anhydrase. Bicarbonate is transported in the blood. Once in the lungs, the reactions reverse direction, and CO2 is regenerated from bicarbonate to be exhaled as metabolic waste.

Calcium

About two pounds of calcium in your body are bound up in bone, which provides hardness to the bone and serves as a mineral reserve for calcium and its salts for the rest of the tissues. Teeth also have a high concentration of calcium within them. A little more than one-half of blood calcium is bound to proteins, leaving the rest in its ionized form. Calcium ions, Ca2+, are necessary for muscle contraction, enzyme activity, and blood coagulation. In addition, calcium helps to stabilize cell membranes and is essential for the release of neurotransmitters from neurons and of hormones from endocrine glands.

Calcium is absorbed through the intestines under the influence of activated vitamin D. A deficiency of vitamin D leads to a decrease in absorbed calcium and, eventually, a depletion of calcium stores from the skeletal system, potentially leading to rickets in children and osteomalacia in adults, contributing to osteoporosis.

Hypocalcemia, or abnormally low calcium blood levels, is seen in hypoparathyroidism, which may follow the removal of the thyroid gland, because the four nodules of the parathyroid gland are embedded in it. This can lead to cardiac depression, increased neuromuscular excitability, muscular cramps, and skeltal weakness. Hypercalcemia, or abnormally high calcium blood levels, is seen in primary hyperparathyroidism. This can lead to cardiac arrhythmias and arrest, muscle weakness, CNS confusion, and coma. Some malignancies may also result in hypercalcemia.

Phosphate

Phosphate is present in the body in three ionic forms: H2PO4−, HPO42, and PO43−. The most common form is HPO42−HPO42−. Bone and teeth bind up 85 percent of the body’s phosphate as part of calcium-phosphate salts. Phosphate is found in phospholipids, such as those that make up the cell membrane, and in ATP, nucleotides, and buffers.

Hypophosphatemia, or abnormally low phosphate blood levels, occurs with heavy use of antacids, during alcohol withdrawal, and during malnourishment. In the face of phosphate depletion, the kidneys usually conserve phosphate, but during starvation, this conservation is impaired greatly. Hyperphosphatemia, or abnormally increased levels of phosphates in the blood, occurs if there is decreased renal function or in cases of acute lymphocytic leukemia. Additionally, because phosphate is a major constituent of the ICF, any significant destruction of cells can result in dumping of phosphate into the ECF.

Regulation of Sodium and Potassium

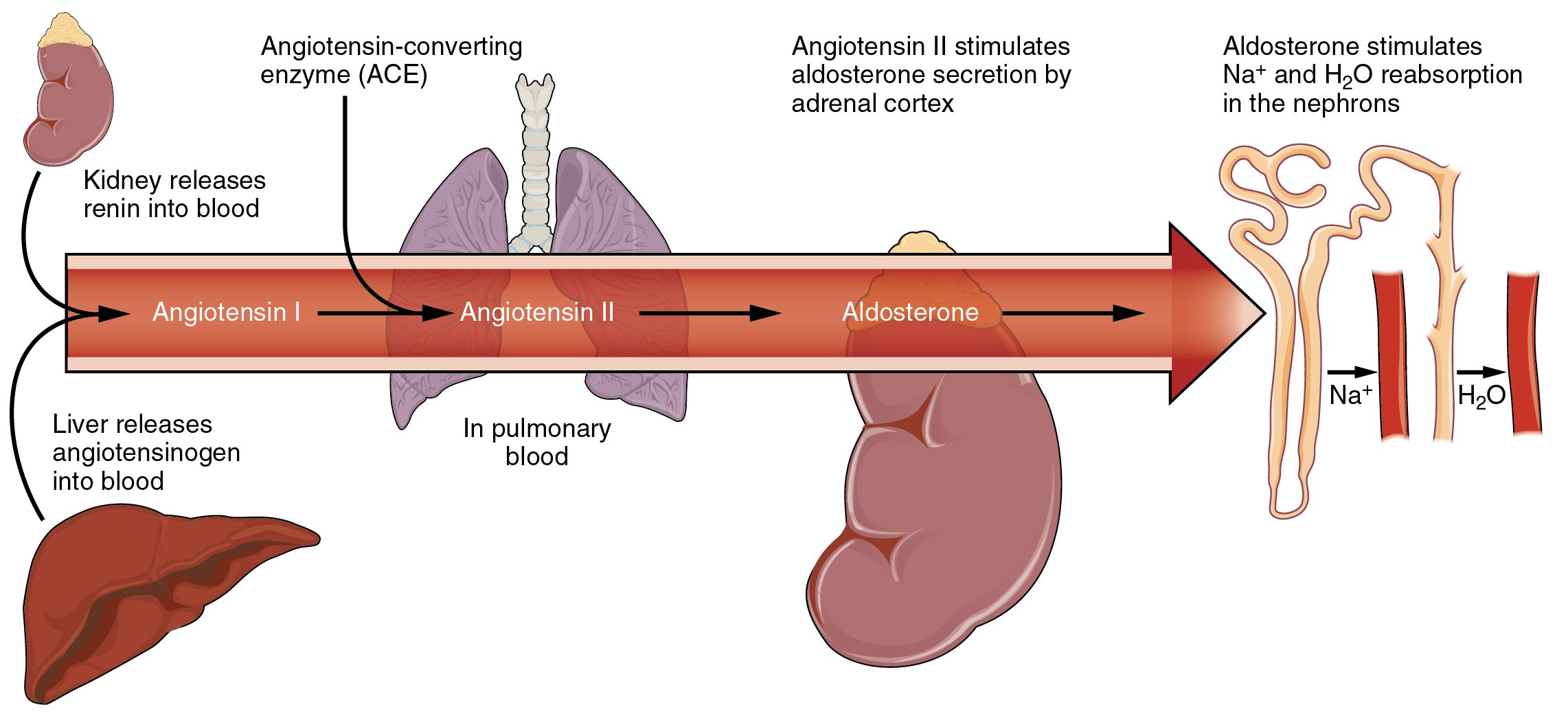

Sodium is reabsorbed from the renal filtrate, and potassium is excreted into the filtrate in the renal collecting tubule. The control of this exchange is governed principally by two hormones—aldosterone and angiotensin II.

Aldosterone

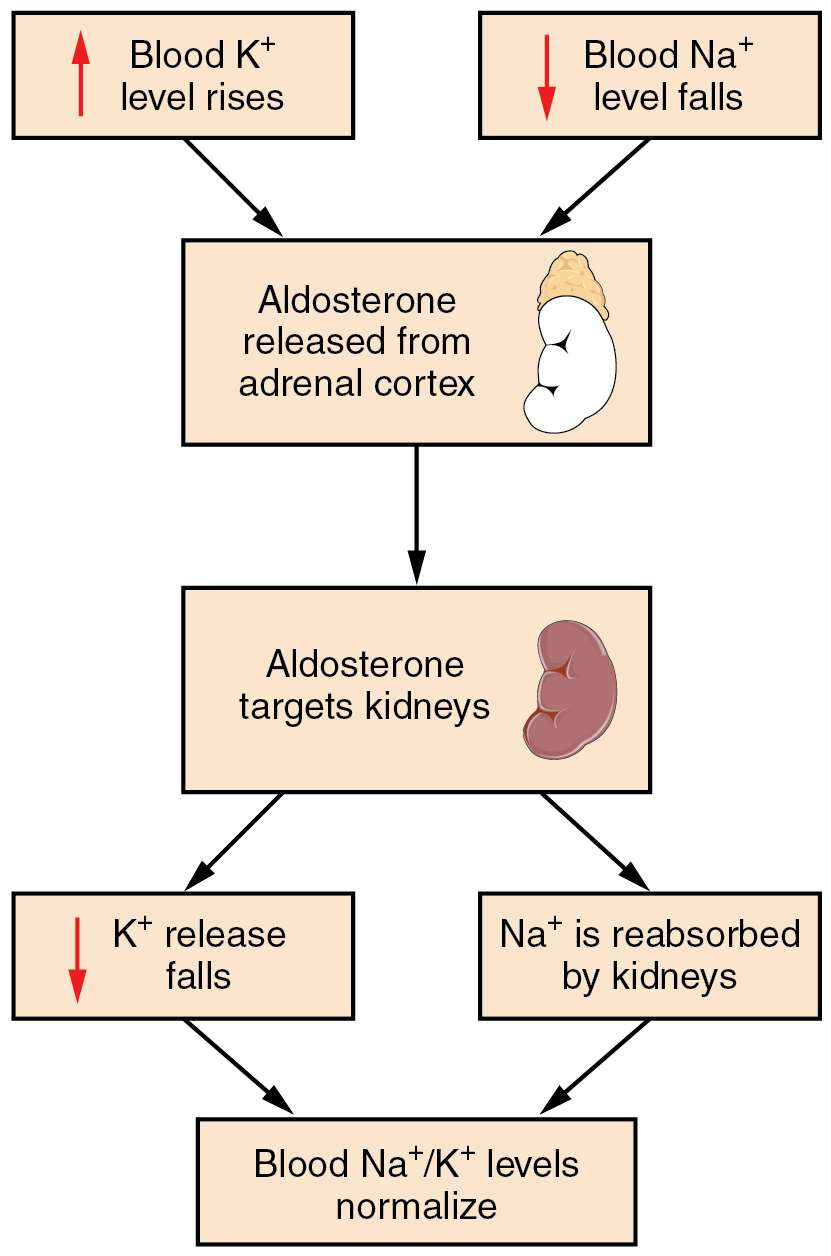

Recall that aldosterone increases the excretion of potassium and the reabsorption of sodium in the distal tubule. Aldosterone is released if blood levels of potassium increase, if blood levels of sodium severely decrease, or if blood pressure decreases. Its net effect is to conserve and increase water levels in the plasma by reducing the excretion of sodium, and thus water, from the kidneys. In a negative feedback loop, increased osmolality of the ECF (which follows aldosterone-stimulated sodium absorption) inhibits the release of the hormone (Figure 26.3.1).

Angiotensin II

Angiotensin II causes vasoconstriction and an increase in systemic blood pressure. This action increases the glomerular filtration rate, resulting in more material filtered out of the glomerular capillaries and into Bowman’s capsule. Angiotensin II also signals an increase in the release of aldosterone from the adrenal cortex.

In the distal convoluted tubules and collecting ducts of the kidneys, aldosterone stimulates the synthesis and activation of the sodium-potassium pump (Figure 26.3.2). Sodium passes from the filtrate, into and through the cells of the tubules and ducts, into the ECF and then into capillaries. Water follows the sodium due to osmosis. Thus, aldosterone causes an increase in blood sodium levels and blood volume. Aldosterone’s effect on potassium is the reverse of that of sodium; under its influence, excess potassium is pumped into the renal filtrate for excretion from the body.

Regulation of Calcium and Phosphate

Calcium and phosphate are both regulated through the actions of three hormones: parathyroid hormone (PTH), dihydroxyvitamin D (calcitriol), and calcitonin. All three are released or synthesized in response to the blood levels of calcium.

PTH is released from the parathyroid gland in response to a decrease in the concentration of blood calcium. The hormone activates osteoclasts to break down bone matrix and release inorganic calcium-phosphate salts. PTH also increases the gastrointestinal absorption of dietary calcium by converting vitamin D into dihydroxyvitamin D (calcitriol), an active form of vitamin D that intestinal epithelial cells require to absorb calcium.

PTH raises blood calcium levels by inhibiting the loss of calcium through the kidneys. PTH also increases the loss of phosphate through the kidneys.

Calcitonin is released from the thyroid gland in response to elevated blood levels of calcium. The hormone increases the activity of osteoblasts, which remove calcium from the blood and incorporate calcium into the bony matrix.

Chapter Review

Electrolytes serve various purposes, such as helping to conduct electrical impulses along cell membranes in neurons and muscles, stabilizing enzyme structures, and releasing hormones from endocrine glands. The ions in plasma also contribute to the osmotic balance that controls the movement of water between cells and their environment. Imbalances of these ions can result in various problems in the body, and their concentrations are tightly regulated. Aldosterone and angiotensin II control the exchange of sodium and potassium between the renal filtrate and the renal collecting tubule. Calcium and phosphate are regulated by PTH, calcitrol, and calcitonin.

Interactive Link Questions

Watch this video to see an explanation of the effect of seawater on humans. What effect does drinking seawater have on the body?

Drinking seawater dehydrates the body as the body must pass sodium through the kidneys, and water follows.

Review Questions

Critical Thinking Questions

1. Explain how the CO2 generated by cells and exhaled in the lungs is carried as bicarbonate in the blood.

2. How can one have an imbalance in a substance, but not actually have elevated or deficient levels of that substance in the body?

Glossary

- dihydroxyvitamin D

- active form of vitamin D required by the intestinal epithelial cells for the absorption of calcium

- hypercalcemia

- abnormally increased blood levels of calcium

- hyperchloremia

- higher-than-normal blood chloride levels

- hyperkalemia

- higher-than-normal blood potassium levels

- hypernatremia

- abnormal increase in blood sodium levels

- hyperphosphatemia

- abnormally increased blood phosphate levels

- hypocalcemia

- abnormally low blood levels of calcium

- hypochloremia

- lower-than-normal blood chloride levels

- hypokalemia

- abnormally decreased blood levels of potassium

- hyponatremia

- lower-than-normal levels of sodium in the blood

- hypophosphatemia

- abnormally low blood phosphate levels

Solutions

Answers for Critical Thinking Questions

- Very little of the carbon dioxide in the blood is carried dissolved in the plasma. It is transformed into carbonic acid and then into bicarbonate in order to mix in plasma for transportation to the lungs, where it reverts back to its gaseous form.

- Without having an absolute excess or deficiency of a substance, one can have too much or too little of that substance in a given compartment. Such a relative increase or decrease is due to a redistribution of water or the ion in the body’s compartments. This may be due to the loss of water in the blood, leading to a hemoconcentration or dilution of the ion in tissues due to edema.

This work, Anatomy & Physiology, is adapted from Anatomy & Physiology by OpenStax, licensed under CC BY. This edition, with revised content and artwork, is licensed under CC BY-SA except where otherwise noted.

Images, from Anatomy & Physiology by OpenStax, are licensed under CC BY except where otherwise noted.

Access the original for free at https://openstax.org/books/anatomy-and-physiology/pages/1-introduction.