Learning Objectives

After studying this chapter, you will be able to:

- Identify the components and anatomy of the lymphatic system

- Discuss the role of the innate immune response against pathogens

- Describe the power of the adaptive immune response to cure disease

- Explain immunological deficiencies and over-reactions of the immune system

- Discuss the role of the immune response in transplantation and cancer

- Describe the interaction of the immune and lymphatic systems with other body systems

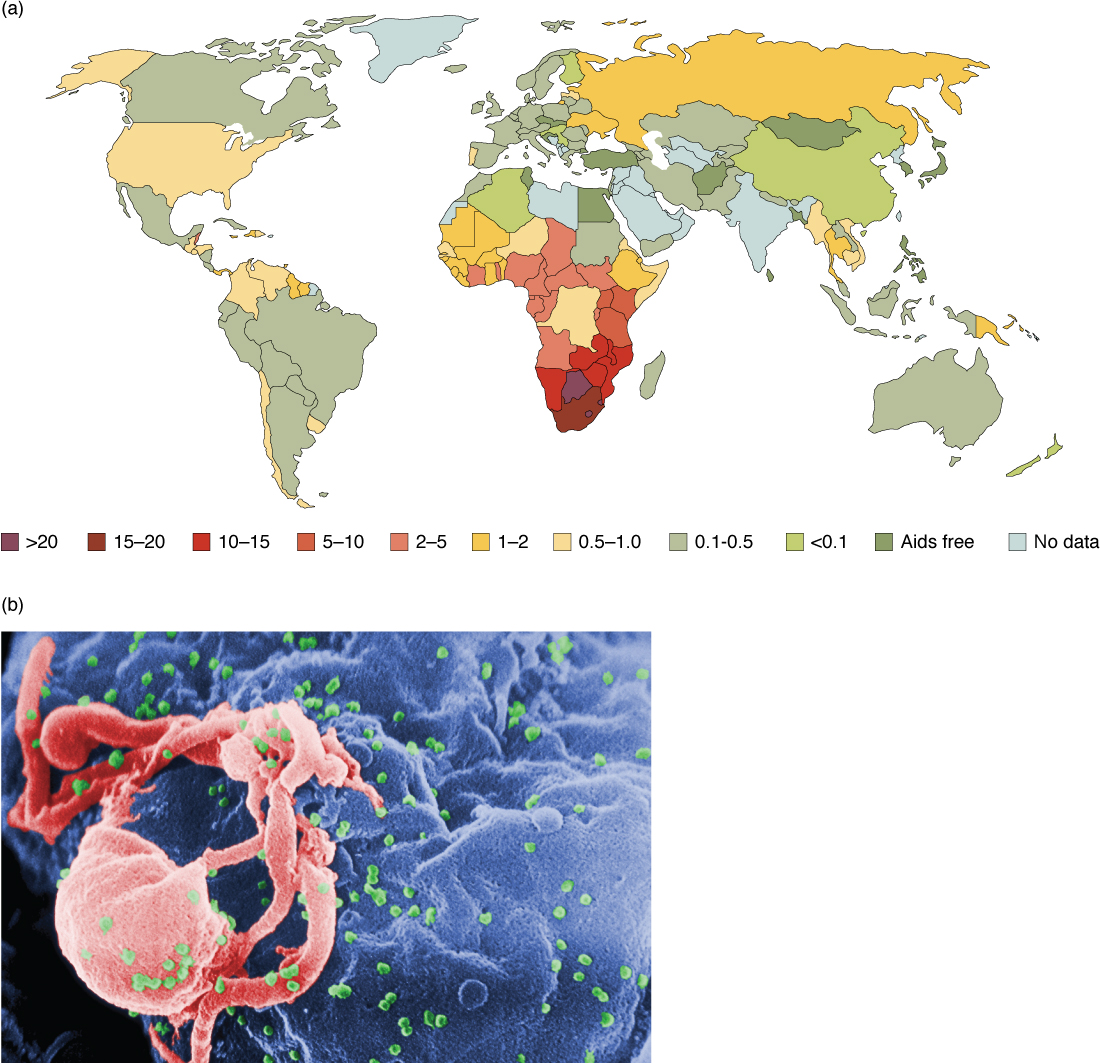

In June 1981, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), in Atlanta, Georgia, published a report of an unusual cluster of five patients in Los Angeles, California. All five were diagnosed with a rare pneumonia caused by a fungus called Pneumocystis jirovecii (formerly known as Pneumocystis carinii).

Why was this unusual? Although commonly found in the lungs of healthy individuals, this fungus is an opportunistic pathogen that causes disease in individuals with suppressed or underdeveloped immune systems. The very young, whose immune systems have yet to mature, and the elderly, whose immune systems have declined with age, are particularly susceptible. The five patients from LA, though, were between 29 and 36 years of age and should have been in the prime of their lives, immunologically speaking. What could be going on?

A few days later, a cluster of eight cases was reported in New York City, also involving young patients, this time exhibiting a rare form of skin cancer known as Kaposi’s sarcoma. This cancer of the cells that line the blood and lymphatic vessels was previously observed as a relatively innocuous disease of the elderly. The disease that doctors saw in 1981 was frighteningly more severe, with multiple, fast-growing lesions that spread to all parts of the body, including the trunk and face. Could the immune systems of these young patients have been compromised in some way? Indeed, when they were tested, they exhibited extremely low numbers of a specific type of white blood cell in their bloodstreams, indicating that they had somehow lost a major part of the immune system.

Acquired immune deficiency syndrome, or AIDS, turned out to be a new disease caused by the previously unknown human immunodeficiency virus (HIV). Although nearly 100 percent fatal in those with active HIV infections in the early years, the development of anti-HIV drugs has transformed HIV infection into a chronic, manageable disease and not the certain death sentence it once was. One positive outcome resulting from the emergence of HIV disease was that the public’s attention became focused as never before on the importance of having a functional and healthy immune system.

This work, Anatomy & Physiology, is adapted from Anatomy & Physiology by OpenStax, licensed under CC BY. This edition, with revised content and artwork, is licensed under CC BY-SA except where otherwise noted.

Images, from Anatomy & Physiology by OpenStax, are licensed under CC BY except where otherwise noted.

Access the original for free at https://openstax.org/books/anatomy-and-physiology/pages/1-introduction.