Module 5.2 Protecting Good Nutrition and Physical Wellness

Learning Objectives

By the end of this module, you should be able to:

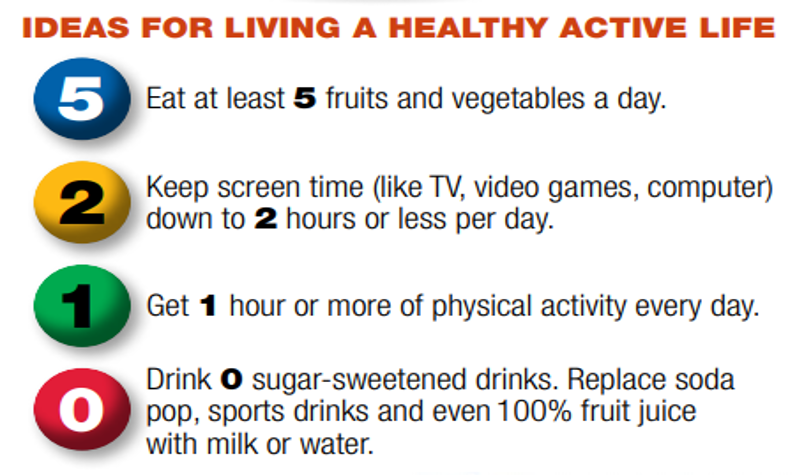

- Explain the 5-2-1-0 recommendation.

- Examine both undernutrition and overnutrition as forms of malnutrition.

- Describe ways early learning and childcare programs can educate children about nutrition.

- Distinguish food allergies from food intolerances.

- Identify strategies early learning and childcare programs can follow when caring for children with food allergies, food intolerances and iron deficiency anemia.

Introduction

Healthy active living includes eating healthy foods, staying physically active, and getting enough rest. Developing healthy habits starts in early childhood. Eating well and being physically active helps a child continue to grow and learn.

Healthy Active Living

Research tells us that the way young children eat, move, and sleep can impact their weight now and in the future. Early childhood is an ideal time to start healthy habits before unhealthy patterns are set.

Young children depend on parents, caregivers, and others to provide environments that foster and shape healthy habits. Early learning and childcare programs have a responsibility to promote growth and development, make healthy foods available, and provide safe spaces for active play. Educators can help children and families by encouraging and modeling healthy eating and physical activity and by providing suggestions for small, healthy steps at home.

5-2-1-0 Message

Engaging Families

Educators can engage families by sharing the recommendations with families with these tips.

5 Fruits and Vegetables a Day

- Go for the rainbow. Each month, pick a color from the rainbow and try to eat a new fruit or veggie of that color (green, purple, orange, yellow, red). It’s a great way for little ones to learn colors while you’re all eating healthy.

- Whenever possible, let your child help get fruits and veggies ready to serve. Maybe he can wash an apple or mix the salad. Your little chef may be more likely to try foods that he helps to prepare.

- Ever feel like fresh fruits and veggies are just too expensive? Try using frozen ones for a few meals every week.

2 Hours or Less of Screen Time a Day

- A great way to cut down on screen time is to make a “no television (or computer) while eating” rule.

- If your children are watching TV, watch with them. Use commercial breaks for an activity break—hula hoop, dance, or come up with a crazy new way to do jumping jacks.

- If you need a break and want to let your child watch TV, set a timer for 30 minutes. You can get a lot done and you’ll know how long they watched.

- Television in your child’s bedroom might seem like a convenience but watching TV close to bedtime can affect your child’s ability to sleep.

1 Hour of Active Play or Physical Activity a Day

- An hour of active play might seem like a lot, but you don’t have to do it all at one time. Try being active for 10–15 minutes several times each day.

- What were your favorite active games when you were a child? They might seem old school to you, but they’ll be new to your child. Try one today.

- Rain or bad weather has you stuck in the house? Don’t let it keep you and your child from being active together. Try one of these fun activities:

- Have an indoor parade.

- Set up a scavenger hunt inside.

- Start your own indoor Olympics—who can jump on one foot the longest or do the most sit ups?

0 Sugary Drinks a Day

- Serve milk with meals and offer water at snack time.

- Let your child pick their favorite “big kid” cup to use for water.

- Think plain water is too boring? Try adding a fruit slice (like orange) for natural flavor.

- Avoid buying juice—if it’s not in the house, no one can drink it.

- If you’re still trying to cut sugary drinks down to zero, keep up the great work! Young children should never have soda pop or sports drinks but if you choose to give juice, please remember:

- Make sure the label says 100 percent fruit juice. Limit the amount to one small cup a day (4-6 ounces if you measure it out).

Nutrition Education

Lifelong eating habits are shaped during a child’s early years. Educators of young children have a special opportunity to help children establish a healthy relationship with food and lay the foundation for sound eating habits. Nutrition education and activities help set children on the path to a healthful lifestyle. Providing nutritionally balanced meals and snacks and integrating nutrition education and healthy eating habits in the home and early childhood.

Nutrition education for preschoolers fosters children’s awareness of different types of foods and promotes exploration and inquiry of food choices. Lifelong habits with foods are developed during early childhood. Through nutrition education in preschool, educators encourage children to include a wide variety of foods that provide adequate nutrients in their daily diet. Through knowledge, children become aware of different foods and tastes, some of which are familiar and others that are new. As they explore various foods and food preparations, they develop likes and dislikes and begin to make choices based on preference. Both nutrition choices and self-regulation of eating—that is, eating when hungry, chewing food thoroughly, eating slowly, and stopping when full— involve decision-making skills.

As children begin to understand the concepts of food identification and categorizing, educators may describe how specific foods help our bodies. Children may better understand the overall benefit of food in terms of it helping them grow, giving them energy to run and play, and helping them to become strong. As children begin to understand internal body parts, educators can initiate discussion of more specific food benefits. Children need to understand that various foods help the body in different ways and that some children have specific food allergies. For those with allergies, certain foods are potentially harmful to them.

Educators should encourage tasting and eating a variety of foods to obtain adequate nutrients for growth and development. “Variety” may mean foods of different color, shape, texture, and taste.

Here are some things educators can do to help children learn about nutrition:

- Introduce many different foods.

- Recognize and accommodate differences in eating habits and food choices.

- Provide opportunities and encouragement in food exploration.

- Integrate nutrition with other areas of learning through cooking activities.

- Show children where food is produced.

- Set up special areas to represent nutrition-related environments, such as grocery stores, restaurants, open-air markets, food co-ops, and picnics.

- Integrate nutrition education with basic hygiene education.

- Model and coach children’s behavior by eating from the same menu and encouraging conversations during mealtimes.

- Encourage children to share information about family meals.

- Serve meals and snacks family-style.

- Encourage tasting and decision making.

- Provide choices for children.

- Offer a variety of nutritious, appetizing foods in small portions.

- Encourage children to chew their food well and eat slowly.

- Teach children to recognize signs of hunger.

- Discuss how the body uses food.

Children learn about food and develop food preferences through their direct experiences with food (i.e., handling, preparing, eating) and by observing the eating behaviors of adults and peers. The goal in preschool is that children will learn to eat a variety of nutritious foods and begin to recognize the body’s physical need for food (i.e., hunger and fullness).

Through modeling, repeated and various exposures to food, and social experiences, children begin to develop eating behaviors that can prevail throughout life.

Pause to Reflect 💭

Reflect on how you will support children’s nutrition educator.

What will be most natural/easiest for you to do from this section? What might you have to be more intentional about (what might be more challenging or less natural)?

Understanding Malnutrition

When children do not receive proper nutrition, it affects their physical health and wellness. For many, the word “malnutrition” produces an image of a child in a third-world country with a bloated belly, and skinny arms and legs. However, this image alone is not an accurate representation of the state of malnutrition. For example, someone who is 150 pounds overweight can also be malnourished.

Malnutrition refers to one not receiving proper nutrition and does not distinguish between the consequences of too many nutrients or the lack of nutrients, both of which impair overall health. Undernutrition is characterized by a lack of nutrients and insufficient energy supply, whereas overnutrition is characterized by excessive nutrient and energy intake. Overnutrition can result in obesity, a growing global health threat. And if the cause of overnutrition is a diet that features food that is not nutrient-dense, a child could experience both overnutrition (too many calories) and undernutrition (inadequate micronutrients).

Undernutrition

Although not as prevalent in North America as it is in developing countries, undernutrition is not uncommon and affects many subpopulations, including the elderly, those with certain diseases, and those in poverty. Undernutrition is most often due to not enough high-quality food being available to eat. This is often related to high food prices and poverty. There are two main types of undernutrition: protein-energy malnutrition and dietary deficiencies. Protein-energy malnutrition has two severe forms: marasmus (a lack of protein and calories) and kwashiorkor (a lack of just protein). Common micronutrient deficiencies include a lack of iron, iodine, and vitamin A.

Undernutrition encompasses stunted growth (stunting), wasting, and deficiencies of essential vitamins and minerals (collectively referred to as micronutrients). Even moderate undernutrition can have lasting effects on children’s cognitive development. When children are hungry or undernourished, they have difficulty resisting infection and therefore are more likely than other children to become sick and to miss school. They are irritable and have difficulty concentrating, which can interfere with learning; and they have low energy, which can limit their physical activity. How many children in Canada experience hunger? Unfortunately, there is no scientific consensus currently exists on how to define or measure hunger. The term hunger, which describes a feeling of discomfort from not eating, has been used to describe undernutrition, especially in reference to food insecurity.

Food Insecurity

Food insecurity is defined as the disruption of food intake or eating patterns because of a lack of money and other resources. According to Statistics Canada, in 2022, 6.9 million people in the ten provinces, which includes almost 1.8 million children, live in food-insecure households. (University of Toronto, n.d.) Food insecurity does not necessarily cause hunger, but hunger is a possible outcome of food insecurity.

Food insecurity may be long term or temporary. It may be influenced by several factors including income, employment, race/ethnicity, and disability.

According to the Canadian Public Health Association “In 2021, at least 15.9% of households, or 5.8 million people across Canada’s provinces were living with insecure or inadequate access to food. This figure is likely much higher for territories, particularly in Nunavut, which had a food insecurity rate of 57% in 2018. There are also racial disparities in food insecurity, with Indigenous and Black households experiencing 2-3 times higher rates than white households.” (Canadian Public Health Association, 2023)

Neighbourhood conditions may affect physical access to food. For example, people living in some urban areas, rural areas, and low-income neighbourhoods may have limited access to full-service supermarkets or grocery stores. Communities that lack affordable and nutritious food are commonly known as “food deserts.” Convenience stores and small independent stores are more common in food deserts than full-service supermarkets or grocery stores. These stores may have higher food prices, lower quality foods, and less variety of foods than supermarkets or grocery stores. Access to healthy foods is also affected by a lack of transportation and long distances between residences and supermarkets or grocery stores.

Overnutrition

Overnutrition is a form of malnutrition (imbalanced nutrition) arising from excessive intake of nutrients, leading to an accumulation of body fat that impairs health (i.e., overweight/obesity). Overnutrition is known to be a risk factor for many diseases, including Type 2 diabetes, cardiovascular disease, inflammatory disorders (such as rheumatoid arthritis), and cancer.

Overweight and Obesity in Childhood

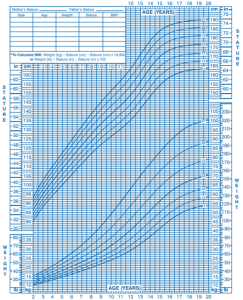

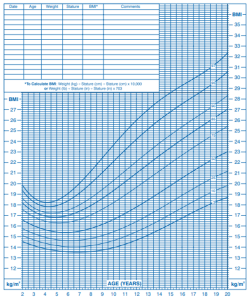

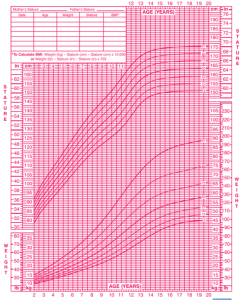

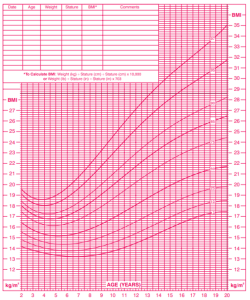

Obesity means having too much body fat. It is different from being overweight, which means weighing too much. Both terms mean that a person’s weight is greater than what’s considered healthy for his or her height. Children grow at different rates, so it isn’t always easy to know when a child has obesity or is overweight. Obesity is defined as a body mass index (BMI) at or above the 95th percentile of the CDC sex-specific BMI-for-age growth charts.

Growth Charts

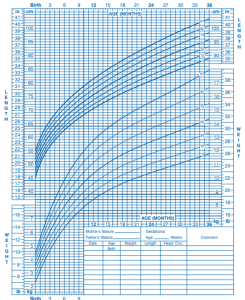

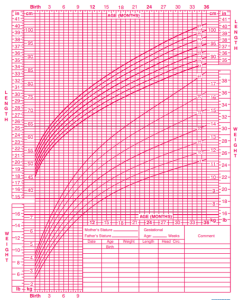

Birth to 36 months (3rd -97th percentile)

Boys Length-for-age and Weight-for-age

Girls Length-for-age and Weight-for-age

Children 2 to 20 years (3rd-97th percentile)

Boys Stature-for-age and Weight-for-age

Boys BMI-for-age

Girls Stature-for-age and Weight-for-age

Girls BMI-for-age

According to the website “Made in CA”, “…the number of obese children is growing… at an alarming rate. Approximately a third of Canadian children and young people up to 17 years of age are overweight or obese. In 1979, the number of overweight or obese children was approximately a quarter. Canadian boys are more likely than girls to be obese and the difference is the highest between 12–17-year-olds. 16.2% of boys in this age are obese compared to 9.3% of girls.” (Made in CA, 2023)

Many factors contribute to childhood obesity, including:

- Genetics: It is estimated that 70-80% of our BMI is predetermined by our genes.

- Metabolism: how your body changes food and oxygen into energy it can use.

- Eating and physical activity behaviors.

- Community and neighborhood design and safety.

- Short sleep duration.

- Negative childhood events.

Genetic factors cannot be changed. However, people and places can play a role in helping children achieve and maintain a healthy weight. Changes in the environments where children spend their time—like homes, early learning and childcare programs, schools, and community settings—can make it easier for children to access nutritious foods and be physically active. Early learning and childcare programs and schools can adopt policies and practices that help young people eat more fruits and vegetables, eat fewer foods and beverages that are high in added sugars or solid fats, and increase daily minutes of physical activity.

Nutrition Concerns During Childhood

To keep children well, it’s also important to be aware of common nutritional concerns during childhood. Two of those concerns are food allergies and intolerances and iron deficiency anemia.

Food Allergies and Food Intolerance

According to Food Allergies Canada, close to 600,000 Canadian children under the age of 18 years have food allergies (Food Allergies Canada, 2023). Common food allergens include peanuts, eggs, shellfish, wheat, and cow’s milk.

An allergy occurs when a protein in food triggers an immune response, which results in the release of antibodies, histamine, and other defenders that attack foreign bodies. Possible symptoms include itchy skin, hives, abdominal pain, vomiting, diarrhea, and nausea. Symptoms usually develop within minutes to hours after consuming a food allergen. Children can outgrow a food allergy, especially allergies to wheat, milk, eggs, or soy.

Anaphylaxis is a life-threatening reaction that results in difficulty breathing, swelling in the mouth and throat, decreased blood pressure, shock, or even death. Milk, eggs, wheat, soybeans, fish, shellfish, peanuts, and tree nuts are the most likely to trigger this type of response. A dose of the drug epinephrine is often administered via a “pen” to treat a person who goes into anaphylactic shock.

Some children experience a food intolerance, which does not involve an immune response. Food intolerance is marked by unpleasant symptoms that occur after consuming certain foods. Lactose intolerance, though rare in very young children, is one example. Children who suffer from this condition experience an adverse reaction to the lactose in milk products. It is a result of the small intestine’s inability to produce enough of the enzyme lactase, which is produced by the small intestine. Symptoms of lactose intolerance usually affect the GI tract and can include bloating, abdominal pain, gas, nausea, and diarrhea. An intolerance is best managed by making dietary changes and avoiding any foods that trigger the reaction.

Caring for Children with Food Allergies

Staff who work in early learning and childcare programs must develop plans for how they will respond effectively to children with food allergies. Although the number of children with food allergies in any one early learning and childcare program may seem small, allergic reactions can be life-threatening and have far-reaching effects on children and their families, as well as on the early learning and childcare programs they attend. Any child with a food allergy deserves attention and the early learning and childcare program must create a plan for preventing an allergic reaction and responding to a food allergy emergency.

39.(1) Every licensee shall ensure that each child care centre it operates and each premises where it oversees the provision of home child care has an anaphylactic policy that includes the following:

1. A strategy to reduce the risk of exposure to anaphylactic causative agents, including rules for parents who send food with their child to the centre or premises.

2. A communication plan for the dissemination of information on life-threatening allergies, including anaphylactic allergies.

3. Development of an individualized plan for each child with an anaphylactic allergy who,

i. receives child care at a child care centre the licensee operates, or

ii. is enrolled with a home childcare agency and receives child care at a premises where it oversees the provision of home child care.

4. Training on procedures to be followed in the event of a child having an anaphylactic reaction. O. Reg. 137/15, s. 39 (1); O. Reg. 126/16, s. 26 (1, 2); O. Reg. 174/21, s. 21; O. Reg. 174/21, s. 1.

(2) The individualized plan referred to in paragraph 3 of subsection (1) shall,

(a) be developed in consultation with a parent of the child and with any regulated health professional who is involved in the child’s health care and who, in the parent’s opinion, should be included in the consultation; and

(b) include a description of the procedures to be followed in the event of an allergic reaction or other medical emergency. O. Reg. 126/16, s. 26 (3).

(3) In this section,

“anaphylaxis” means a severe systemic allergic reaction which can be fatal, resulting in circulatory collapse or shock, and “anaphylactic” has a corresponding meaning. O. Reg. 137/15, s. 39 (3).

Children with medical needs

39.1 (1) Every licensee shall develop an individualized plan for each child with medical needs who,

(a) receives child care at a child care centre it operates; or

(b) is enrolled with a home child care agency and receives child care at a premises where it oversees the provision of home child care. O. Reg. 126/16, s. 27; O. Reg. 174/21, s. 1.

(2) The individualized plan shall be developed in consultation with a parent of the child and with any regulated health professional who is involved in the child’s health care and who, in the parent’s opinion, should be included in the consultation. O. Reg. 126/16, s. 27.

(3) The plan shall include,

(a) steps to be followed to reduce the risk of the child being exposed to any causative agents or situations that may exacerbate a medical condition or cause an allergic reaction or other medical emergency;

(b) a description of any medical devices used by the child and any instructions related to its use;

(c) a description of the procedures to be followed in the event of an allergic reaction or other medical emergency;

(d) a description of the supports that will be made available to the child in the child care centre or premises where the licensee oversees the provision of home child care; and

(e) any additional procedures to be followed when a child with a medical condition is part of an evacuation or participating in an off-site field trip. O. Reg. 126/16, s. 27; O. Reg. 174/21, s. 1.

(4) Despite subsection (1), a licensee is not required to develop an individualized plan under this section for a child with an anaphylactic allergy if the licensee has developed an individualized plan for the child under section 39 and the child is not otherwise a child with medical needs. O. Reg. 126/16, s. 27. (O. Reg. 137/15: GENERAL)

In addition to the above shown sections of O. Reg. 137/15: GENERAL, Section 40(2) allows a child to carry their own asthma or emergency allergy medication provided there is a written procedure for administering the medication and recording the administering of the medication. (O. Reg. 137/15: GENERAL)

The symptoms of allergic reactions to food vary both in type and severity among individuals and even in one individual over time. Symptoms associated with an allergic reaction to food include the following:

- Mucous Membrane Symptoms: red watery eyes or swollen lips, tongue, or eyes.

- Skin Symptoms: itchiness, flushing, rash, or hives.

- Gastrointestinal Symptoms: nausea, pain, cramping, vomiting, diarrhea, or acid reflux.

- Upper Respiratory Symptoms: nasal congestion, sneezing, hoarse voice, trouble swallowing, dry staccato cough, or numbness around mouth.

- Lower Respiratory Symptoms: deep cough, wheezing, shortness of breath or difficulty breathing, or chest tightness.

- Cardiovascular Symptoms: pale or blue skin color, weak pulse, dizziness or fainting, confusion or shock, hypotension (decrease in blood pressure), or loss of consciousness.

- Mental or Emotional Symptoms: a sense of “impending doom,” irritability, change in alertness, mood change, or confusion.

Children sometimes do not exhibit overt and visible symptoms after ingesting an allergen, making early diagnosis difficult. Signs and symptoms can become evident within a few minutes or up to 1–2 hours after ingestion of the allergen, and rarely, several hours after ingestion.

Children might communicate their symptoms in the following ways:

- It feels like something is poking my tongue.

- My tongue (or mouth) is tingling (or burning).

- My tongue (or mouth) itches.

- My tongue feels like there is hair on it.

- My mouth feels funny.

- There’s a frog in my throat; there’s something stuck in my throat.

- My tongue feels full (or heavy).

- My lips feel tight.

- It feels like there are bugs in there (to describe itchy ears).

- It (my throat) feels thick.

- It feels like a bump is on the back of my tongue (throat).

Some children may not be able to communicate their symptoms clearly because of their age or developmental challenges.

Emotional Impact on Children with Food Allergies and Their Families

The health of a child with a food allergy can be compromised at any time by an allergic reaction to food that is severe or life-threatening. Many studies have shown that food allergies have a significant effect on the psychosocial well-being of children with food allergies and their families.

Families of a child with a food allergy may have constant fear about the possibility of a life-threatening reaction and stress from constant vigilance needed to prevent a reaction. They also must trust their child to the care of others, make sure their child is safe outside the home, and help their child have a normal sense of identity.

Children with food allergies may also have constant fear and stress about the possibility of a life-threatening reaction. The fear of ingesting a food allergen without knowing it can lead to coping strategies that limit social and other daily activities. Children can carry emotional burdens because they are not accepted by other people, they are socially isolated, or they believe they are a burden to others. They also may have anxiety and distress that is caused by teasing, taunting, harassment, or bullying by peers, teachers, or other adults. Educators must consider these factors as they develop plans for managing the risk of food allergy for children with food allergies.

Food Allergy Management in Early Care and Education Programs

In Ontario, O. Reg. 137/15: GENERAL requires early learning and childcare programs to develop a comprehensive strategy to manage the risk of food allergy reactions in children. This strategy should include (1) a coordinated approach, (2) strong leadership, and (3) a specific and comprehensive plan for managing food allergies.

- Use a coordinated approach that is based on effective partnerships. The management of any chronic health condition should be based on a partnership among the early learning and childcare program staff, children and their families, and the family’s allergist or other doctor.

- The collective knowledge and experience of a licensed doctor, children with food allergies, and their families can guide the most effective management of food allergies in early learning and childcare programs for each child. Close working relationships can help ease anxiety among parents, build trust, and improve the knowledge and skill of program staff members.

- Provide clear leadership to guide planning and ensure implementation of food allergy management plans and practices. This may be the administrator or the person that coordinates health services for children (health consultant, school nurse, etc.)

- Develop and implement a comprehensive plan for managing food allergies. To effectively manage food allergies and the risks associated with these conditions, many people inside and outside the early learning and childcare program must come together to develop a comprehensive plan.

Gluten Intolerance

One particular intolerance to be aware of that may affect children in early learning and childcare programs is gluten intolerance. Gluten is a protein found in wheat, rye, and barley. It is found mainly in foods but may also be in other products like medicines, vitamins, and supplements. People with gluten sensitivity have problems with gluten. It is different from celiac disease (see below), an immune disease in which people can’t eat gluten because it will damage their small intestine.

Some of the symptoms of gluten sensitivity are similar to celiac disease. They include tiredness and stomach-aches. It can cause other symptoms too, including muscle cramps and leg numbness. But it does not damage the small intestine like celiac disease.

Researchers are still learning more about gluten sensitivity. A more serious concern surrounding gluten that has more acknowledgment in the medical field is celiac disease.

Celiac Disease

Celiac disease is an immune disease in which people can’t eat gluten because it will damage their small intestine. If they have celiac disease and eat foods with gluten, the immune system responds by damaging the small intestine. Gluten is a protein found in wheat, rye, and barley. It may also be in other products like vitamins and supplements, hair and skin products, toothpaste, and lip balm.

Celiac disease affects each person differently. Symptoms may occur in the digestive system, or other parts of the body. One person might have diarrhea and abdominal pain, while another person may be irritable or depressed. Irritability is one of the most common symptoms in children. Some people have no symptoms.

Celiac disease is genetic. Blood tests and tissue biopsies may be used to diagnose celiac disease. Children are usually diagnosed with it when they’re between 6 months and 2 years old, which is when children start to be exposed to foods that contain gluten. Treatment is a diet free of gluten which is essential to prevent damage to the small intestine. So, it is critical that their food does not contain and is not contaminated with gluten. Because gluten is found in many foods, reading nutrition labels will be vital. Preparing food away from gluten containing food is also required to prevent cross-contamination. Gluten free versions of foods and gluten-free recipes will help early learning and childcare programs to protect the nutritional well-being and health of children with celiac disease.

Pause to Reflect 💭

What are five things you think every adult who cares for children should know about food allergies and intolerances?

Iron-Deficiency Anemia (IDA)

According to the National Institute of Health, between 3.5% of 10.5% of Canadian children in the general population have IDA. However, in two Northern Ontario First Nations communities and one Inuit community, 36% of children were anemic and 56% had depleted iron levels (Christofides et.al., 2005).

This condition occurs when an iron-deprived body cannot produce enough hemoglobin, a protein in red blood cells that transports oxygen throughout the body. The inadequate supply of hemoglobin for new blood cells results in anemia. Iron-deficiency anemia causes several problems including weakness, pale skin, shortness of breath, and irritability. It can also result in intellectual, behavioural, or motor problems.

In infants and toddlers, iron-deficiency anemia can occur as young children are weaned from iron-rich foods, such as breast milk and iron-fortified formula. They begin to eat solid foods that may not provide enough of this nutrient. As a result, their iron stores become diminished at a time when this nutrient is critical for brain growth and development.

There are steps that parents and caregivers can take to prevent iron-deficiency anemia, such as adding more iron-rich foods to a child’s diet, including lean meats, fish, poultry, eggs, legumes, and iron-enriched whole-grain breads and cereals and foods high in vitamin C, which helps the body absorb iron efficiently. Although milk is critical for the bone-building calcium that it provides, intake should not exceed the recommended daily allowance (RDA) to avoid displacing foods rich with iron.

Important Things to Remember

- Lifelong eating habits are shaped during a child’s early years.

- Children learn about food and develop food preferences through their direct experiences with food and by observing the eating behaviors of adults and peers.

- Nutrition education for preschoolers fosters children’s awareness of different types of foods and promotes exploration and inquiry of food choices.

- Children grow at different rates, so it isn’t always easy to know when a child has obesity or is overweight.

- The symptoms of allergic reactions to food vary both in type and severity among individuals and even in one individual over time.

Resources for Further Exploration

References

- Canadian Public Health Association (2023). Household food insecurity: its not just about food. https://www.cpha.ca/household-food-insecurity-its-not-just-about-food#:~:text=In%202021%2C%20at%20least%2015.9,rate%20of%2057%25%20in%202018.

- Christofides A, Schauer C, Zlotkin SH. (2005). Iron deficiency anemia among children: Addressing a global public health problem within a Canadian context. Paediatr Child Health. 2005 Dec;10(10):597-601. doi: 10.1093/pch/10.10.597. PMID: 19668671; PMCID: PMC2722615.

- Food Allergies Canada (2023). Food allergy FAQs. https://foodallergycanada.ca/food-allergy-basics/food-allergies-101/food-allergy-faqs/#:~:text=There%20is%20no%20cure%20for,18%20years%20have%20food%20allergies.

- Made in CA (2023). Obesity Statistics in Canada. https://madeinca.ca/obesity-statistics-canada/#:~:text=Childhood%20Obesity%20in%20Canada&text=Canadian%20boys%20are%20more%20likely,compared%20to%209.3%25%20of%20girls.

- O.Reg. 137/15: GENERAL. https://www.ontario.ca/laws/regulation/150137#BK49

- University of Toronto, (n.d.). How many Canadians are affected by household food insecurity? https://proof.utoronto.ca/food-insecurity/how-many-canadians-are-affected-by-household-food-insecurity/#:~:text=Statistics%20Canada%20recently%20released%20new,in%20a%20food%2Dinsecure%20household.