4

These are difficult stories. We bear witness in this chapter to the role of sport in furthering the settler colonial projects throughout Turtle Island. Here are some supports to access in the community and from a distance:

First Peoples House of Learning Cultural Support & Counselling

Niijkiwendidaa Anishnaabekwag Services Circle (Counselling & Healing Services for Indigenous Women & their Families) – 1-800-663-2696

Nogojiwanong Friendship Centre (705) 775-0387

Peterborough Community Counselling Resource Centre: (705) 742-4258

Hope for Wellness – Indigenous help line (online chat also available) – 1-855-242-3310

LGBT Youthline: askus@youthline.ca or text (647)694-4275

National Indian Residential School Crisis Line – 1-866-925-4419

Talk4Healing (a culturally-grounded helpline for Indigenous women):1-855-5544-HEAL

Section One: History

A) The Residential School System

Exercise 1: Notebook Prompt

We are asked to honour these stories with open hearts and open minds.

Which part of the chapter stood out to you? What were your feelings as you read it? (50 words)

| The chapter’s account of how Indigenous children were denied joyful, culturally-rooted play deeply moved me. I was apauled at how recreation a most simple human joy was controlled and weaponized. It made me feel alot of sadness, but also admiration for the resilience of Indigenous youth who found ways to reclaim their culture and spirits.

|

B) Keywords

Exercise 2: Notebook Prompt

Briefly define (point form is fine) one of the keywords in the padlet (may be one that you added yourself).

|

C) Settler Colonialism

Exercise 3: Complete the Activities

Exercise 4: Notebook Prompt

Although we have discussed in this module how the colonial project sought to suppress Indigenous cultures, it is important to note that it also appropriates and adapts Indigenous cultures and “body movement practices” (75) as part of a larger endeavour to “make settlers Indigenous” (75).

What does this look like? (write 2 or 3 sentences)

| I think that is when settlers use Indigenous symbols, dances, or spiritual practices without understanding their cultural significance, often using them in ways that strip them of context. It might also involve incorporating Indigenous-inspired movements into settler sports or recreational activities to claim a sense of belonging to the land, while continuing to ignore Indigenous rights and voices.

|

D) The Colonial Archive

Exercise 5: Complete the Activities

Section Two: Reconciliation

A) Reconciliation?

Exercise 6: Activity and Notebook Prompt

Visit the story called “The Skate” for an in-depth exploration of sport in the residential school system. At the bottom of the page you will see four questions to which you may respond by tweet, facebook message, or email:

How much freedom did you have to play as a child?

What values do we learn from different sports and games?

When residential staff took photos, what impression did they try to create?

Answer one of these questions (drawing on what you have learned in section one of this module or prior reading) and record it in your Notebook.

| Subject: Reflections on Residential School Photography and Sports

Dear Proff Kelly McGuire I wanted to share my thoughts in response to the question: When residential staff took photos, what impression did they try to create? From what I’ve learned in this module and the story The Skate, it’s clear that the photos taken by residential school staff were meant to portray the schools in a positive light. They often showed Indigenous children playing sports like hockey to suggest that the schools were supportive, joyful places. These images created a misleading impression of success and well-being, masking the harsh realities of abuse, cultural suppression, and neglect. In truth, sports were a rare outlet for the children a form of survival, not celebration. The photos were part of a broader colonial effort to promote assimilation and justify the residential school system to the public. Best regards,

|

B) Redefining Sport

B) Sport as Medicine

Exercise 7: Notebook Prompt

Make note of the many ways sport is considered medicine by the people interviewed in this video.

| In the video, people talk about how sport is like medicine for Indigenous communities. They describe it as a gift from the Creator, especially games like lacrosse, which is called the “medicine game.” For many in the community, sports have been a way to heal from the trauma caused by residential schools. It helps bring people back together, rebuild a sense of community, and reconnect with culture. |

C) Sport For development

Exercise 7: Notebook Prompt

What does Waneek Horn-Miller mean when she says that the government is “trying but still approaching Indigenous sport development in a very colonial way”?

| “Sport for development” sounds like a good idea… by using sports to improve lives and communities. But the problem is, it often pushes a one-size-fits-all solution without considering what marginalized groups actually need. It can also overlook the voices of those affected, especially Indigenous communities who aren’t always able to shape their own priorities. Waneek Horn-Miller calls this a “colonial approach” because the government often tries to push its own idea of what Indigenous sport development should look like, without understanding or respecting Indigenous values. In the case of hockey, it’s used to unify Canadians, but it can also reinforce the idea that Indigenous people are just recipients of colonial benevolence, rather than active participants in defining their own future. |

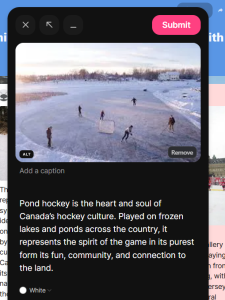

Exercise 8: Padlet Prompt

Add an image or brief comment reflecting some of “binding cultural symbols that constitute Canadian hockey discourse in Canada.” Record your responses in your Notebook as well.

|

Long Prompt:

Call to Action #89 calls for the federal government to amend the Physical Activity and Sport Act to ensure that policies are inclusive of Indigenous peoples. This includes promoting physical activity as part of health and well-being, reducing barriers to sports participation, increasing excellence in sport, and building capacity within the Canadian sport system. Steps toward fulfilling this call have been taken, though progress is ongoing. One significant example is the Indigenous Sport, Physical Activity and Recreation Council (ISPARC), which works with the federal government to develop and implement physical activity programs specifically for Indigenous communities. This includes supporting local and regional sports initiatives that make sports more accessible by addressing barriers like lack of facilities, funding, and transportation. Additionally, the Aboriginal Sport Circle has advocated for policies that ensure Indigenous communities have equal access to sports and physical activities, which includes fostering Indigenous leadership in the sport system. These efforts aim to ensure that sports are not just about participation but about providing opportunities for excellence, including pathways for Indigenous athletes to succeed at national and international levels. However, challenges remain. While some initiatives have made significant strides, systemic issues like underfunding, lack of infrastructure, and cultural insensitivity still exist. These need to be addressed in order to fully fulfill the spirit of the Call to Action. As for how settlers can contribute, they can support Indigenous-led sports initiatives, advocate for policies that reduce barriers to sports, and work to ensure that physical activities reflect Indigenous culture and values. Settlers can also attend and support Indigenous sports events, helping to amplify Indigenous voices in the sport community and contribute to reconciliation.