The film Murderball definitely showcases a resistance to marginalized masculinity. The wheelchair rugby players, who face significant physical challenges, resist traditional ideas of masculinity by proving they are strong, tough, and competitive, even within the constraints of their disabilities. They engage in an aggressive, physical sport that defies the stereotypical idea that disability equals weakness, showing that they can still embody a form of masculinity that is raw, athletic, and powerful.However, at the same time, Murderball also reinforces ableist norms of masculinity. The focus on aggression, strength, and competition reflects traditional ideas of masculinity that often exclude people with disabilities from the conversation. While the athletes in the film are challenging stereotypes about disability, they are also playing into the mainstream masculine ideals of toughness and dominance, which can be seen as ableist. This type of masculinity tends to favor able-bodied traits, suggesting that true masculinity is linked to physical strength and dominance, even if that strength is demonstrated in a wheelchair.

5

Section one: The fundamentals

A)

Exercise 1: Notebook Prompt

Many of you are likely familiar with the concept of “ability inequity,” which the authors of this article define as “an unjust or unfair (a) ‘distribution of access to and protection from abilities generated through human interventions’ or (b) ‘judgment of abilities intrinsic to biological structures such as the human body’.”

However, they go on to identify the following “ability concepts” that are less familiar:

1) ability security (one is able to live a decent life with whatever set of abilities one has)

2) ability identity security (to be able to be at ease with ones abilities)

How prevalent are these forms of security among disabled people you know? Or, if you identify as a disabled person, would you say your social surroundings and community foster and support these kinds of security? Furthermore, while the focus of the article is on Kinesiology programs, it is also important to reflect on how academia in general accommodates for disability. If you feel comfortable answering this question, what has been your experience of postsecondary education to date?

-OR-

The authors also observe that “Ableism not only intersects with other forms of oppression, such as racism, sexism, ageism, and classism, but abilities are often used to justify such negative ‘isms’.”

What do you think this means? Provide an example.

| I think the quote means that ableism overlaps with other forms of oppression like racism, sexism, and classism. Society sometimes uses abilities (or perceived lack of abilities) to justify these negative attitudes. For example, a disabled woman of color might face discrimination not only for her disability but also because of her race and gender, making her experiences even more complex. In hiring, employers might assume she’s less qualified because of her disability and also consider her race or gender, compounding the discrimination that she faces.

|

Exercise 2: Implicit Bias Test

Did anything surprise you about the results of the test? Please share if you’re comfortable OR comment on the usefulness of these kinds of tests more generally.

| Honestly, I was kind of surprised by my results. I didn’t expect to have certain biases I wasn’t fully aware of. It made me realize that even though I try to be open-minded and inclusive, there are still unconscious thoughts or preferences that pop up. It was a little humbling, but it’s also super useful because now I know I need to be more conscious about those biases, especially when interacting with people from different backgrounds. I think these kinds of tests are a good wake-up call, even if they don’t always tell the whole story. It’s just a tool to make you reflect and maybe change certain habits. |

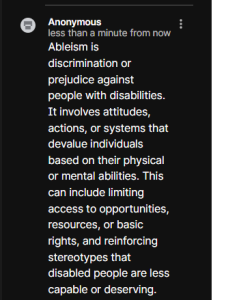

B) Keywords

Exercise 3:

Add the keyword you contributed to padlet and briefly (50 words max) explain its importance to you.

|

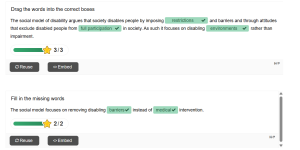

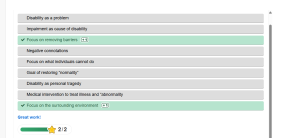

B) On Disability

Exercise 4: Complete the Activities

Exercise 5: Notebook Prompt

What do Fitzgerald and Long identify as barriers to inclusion and how might these apply to sport in particular?

Fitzgerald and Long point out several barriers to inclusion, like attitudinal, physical, social, and systemic ones. Attitudinal barriers happen when people have negative stereotypes about those with disabilities, which can lead to exclusion especially in sports where disabled athletes might not be taken seriously. Physical barriers are things like inaccessible facilities or a lack of adaptive equipment that make it harder for people with disabilities to play. Social barriers can make people feel isolated, as they might not have the same support or opportunities to join teams or sports communities. Systemic barriers are more about rules or policies that unintentionally leave disabled people out, like not having enough funding or programs for adaptive sports. All of these barriers show up in sports, where the standard setup often doesn’t take into account the needs of disabled athletes, limiting their chances to get involved.

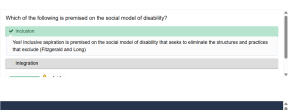

C) Inclusion, Integration, Separation

Exercise 6: Complete the Activities

Exercise 7: Notebook Prompt

Choose ONE of the three questions Fitzgerald and Long argue disability sport needs to address and record your thoughts in your Notebook.

- Should sport be grouped by ability or disability?

- Is sport for participation or competition?

- Should sport competitions be integrated?

| Should sport competitions be integrated?

Fitzgerald and Long argue that integrating sport competitions, where athletes with disabilities compete alongside those without, can be beneficial in many ways. I think this could lead to greater visibility for athletes with disabilities, help challenge stereotypes, and show that people with disabilities can compete at a high level. However, it’s important to recognize that not all athletes with disabilities may be ready to compete against able-bodied athletes due to different levels of access, resources, and training. So, while integration could foster inclusivity and break down barriers, there should also be spaces where athletes with disabilities can thrive in their own categories, without feeling like they have to meet the standards of able-bodied competitors. Ideally, I think sport should aim for integration, but also allow for separate divisions to ensure fairness and equality. This way, the benefits of both inclusion and specialized competition can be achieved.

|

Part Two: Making Connections

A) Gender, Sport and Disability

Exercise 8: Complete the Activity

The paradox that sportswomen habitually face (as the authors observe, this isn’t confined to disabled sportswomen) involves the expectation they will be successful in a ‘masculine’ environment while complying with femininity norms in order to be recognized as a woman.

True or false?

Take a moment to reflect on this paradox below (optional).

B) Masculinity, Disability, and Murderball

Exercise 9: Notebook/Padlet Prompt

Watch the film, Murderball and respond to the question in the padlet below (you will have an opportunity to return to the film at the end of this module).

The authors of “Cripping Sport and Physical Activity: An Intersectional Approach to Gender and Disability” observe that the “gendered performance of the wheelchair rugby players can…be interpreted as a form of resistance to marginalized masculinity” (332) but also point out that it may reinforce “ableist norms of masculinity.” After viewing the film, which argument do you agree with?

a) Murderball celebrates a kind of resistance to marginalized masculinity

Section Three: Taking a Shot

A) Resistance

B) Calling out Supercrip

Exercise 10: Mini Assignment (worth 5% in addition to the module grade)

1) Do you agree with the critique of the “supercrip” narrative in this video? Why or why not? Find an example of the “supercrip” Paralympian in the 2024 Paris Paralympics or Special Olympics coverage and explain how it works.

|

Yes, I agree with the critique of the “supercrip” narrative presented in the video. This narrative frequently oversimplifies and distorts the experiences of athletes with disabilities by reducing them to their impairments and framing their accomplishments as extraordinary merely because they have “overcome” adversity. While it’s undeniable that many of these athletes have faced significant challenges, constantly emphasizing their disabilities risks reinforcing narrow stereotypes that suggest people with disabilities must achieve something exceptional to be valued or recognized. It also shifts focus away from their actual talent, discipline, and athleticism, which should be at the forefront of any sports coverage. One notable example of the “supercrip” narrative can be seen in the media coverage of 15-year-old French sprinter Marie Ngoussou during the 2024 Paris Paralympics. The media was quick to highlight her personal backstory, including the birth injury that led to her disability, and her swift ascent in the world of parasports. Although her story is undoubtedly inspiring, the way it was presented often centered more on her perceived triumph over adversity rather than her athletic abilities, training regimen, or competitive achievements. This type of storytelling, while often well-intentioned, can unintentionally diminish the perception of disabled athletes as serious competitors, positioning them instead as figures of inspiration meant to uplift able-bodied audiences. To move past this limited and sometimes patronizing narrative, it is crucial for media and audiences alike to reframe how disabled athletes are portrayed. Rather than highlighting their disabilities as the defining aspect of their identity or success, the focus should shift to their skills, strategies, dedication, and performance. Recognizing them as athletes first allows for a more accurate, respectful, and inclusive representation that doesn’t rely on outdated or sensationalized tropes. Ultimately, this approach promotes a richer understanding of athleticism that includes all bodies and abilities, and helps challenge broader societal assumptions about disability.

|

2) Does the film Murderball play into the supercrip narrative in your opinion? How does gender inform supercrip (read this blog for some ideas)?

(300 words for each response)

|

Yes, in my opinion, Murderball definitely engages with the “supercrip” narrative, but it also complicates and challenges it in interesting ways. On one hand, the film portrays athletes with disabilities as incredibly intense, fiercely competitive, and physically aggressive traits that we commonly associate with traditional notions of masculinity. These portrayals line up with the classic supercrip trope, where individuals with disabilities are seen as extraordinary simply for participating in high-level sports or pushing their bodies beyond what is socially expected. The focus is often less on their athletic abilities or strategic skill, and more on how they’ve supposedly “defied the odds” by doing something that society didn’t expect from disabled people. This framing can be problematic, because it reinforces the idea that people with disabilities are only worthy of admiration if they do something that feels exceptional or “superhuman.” It centers inspiration rather than ability, and can subtly suggest that a disabled person’s value lies in how well they can mimic or exceed able-bodied norms. But, at the same time, the film complicates this narrative by refusing to present its subjects as saintly or one-dimensional. The athletes in Murderball are shown as fully human with flaws, egos, aggression, humor, and even pettiness. They’re not portrayed as passive or pitiable, which is often the default in disability representation, but instead as tough, driven individuals who happen to be in wheelchairs. However, this toughness is heavily coded through masculinity. As the blog points out, the supercrip image often leans on hyper-masculine ideals like independence, strength, stoicism, and dominance. In Murderball, these values are foregrounded in nearly every scene whether it’s through trash-talking opponents, brutal full-contact gameplay, or the athletes discussing sex, dating, and personal pride. There’s a clear effort by the players to assert themselves not just as athletes, but as “real men,” which reveals how deeply able-bodied ideas of masculinity are woven into the narrative.

|