2 Introduction to interpreting gross lesions, and the postmortem diagnostic process

How to investigate gross lesions

1. Identify the lesions

- Identify the tissue and normal structures

- Recognize artefacts and incidental findings

- Identify the abnormality

2. Describe the lesions

3. Interpret the lesions

- Infer the pathologic process

- Construct a morphologic diagnosis

4. Interpret the likely cause, clinical appearance, histologic correlates, pathogenesis

Concepts of disease

We can consider the development of disease on several conceptual levels. It is important to understand these terms—disease name, cause, pathologic process, pathogenesis—because these are they ways in which we understand how disease develops. For students, on a more trivial level, these terms are always the subject of exam questions, and so understanding these terms is necessary to know what is being asked on an exam.

Name of the disease is the name that we commonly call the disease, such as paratuberculosis, strangles, or diabetes mellitus. There is an effort to eliminate eponymous disease names — for example, paratuberculosis rather than Johne’s disease, and hyperadrenocorticism rather than Cushing’s disease — based on the assumption that the existence of these diseases is independent of the person who discovered them.

Cause is what initially induces the disease or incites its development. The cause may be an external substance, and exposure of the animal to this substance triggered development of disease. Other causes can be intrinsic, such as genetic mutations or autoimmunity. Examples of causes are Mycobacterium paratuberculosis, feline alphaherpesvirus 1, lead (lead poisoning), acetaminophen (acetaminophen toxicity), vitamin D deficiency, exposure to heat or cold, trauma, and mutation in the gene MYBPC3. (These are sometimes called etiologies, but etiology is technically the scientific discipline involving the study of causation … some trivia).

Lesion is an observed change within a tissue, that developed prior to death. It is real, and can be observed or measured in some way. Lesions can be detected grossly (e.g. multiple white nodules in a liver, or firmness of the cranioventral lung), or microscopically (neutrophils within the grey matter of the brain; hypereosinophilic cytoplasm and pyknotic nuclei in hepatocytes).

Clinical signs are abnormalities that can be observed in a live animal. Examples include cough, difficulty breathing, reduced food intake, lameness, seizures, fever, etc. Note that symptoms are perceived subjectively by the patient, such as nausea. Thus, we are unable to perceive symptoms in non-human animals, and non-human animals only show clinical signs.

Pathologic process is the concept of what is occurring within the tissue, induced by the cause of the disease. Examples of pathologic processes are inflammation, neoplasia, necrosis, hyperplasia, mineralization, fibrosis, and many others. The pathologic process is not something we observe (those are lesions or clinical signs) but instead is a conceptual idea of what is occurring within the tissues.

Pathogenesis is an explanation or a story of how the disease developed. The pathogenesis begins with the inciting cause or initial incident, then describes the sequence of events leading to the observed lesions or clinical signs. For example:

- The pathogenesis of subcutaneous edema in paratuberculosis (Johne’s disease) is:

Mycobacterium paratuberculosis infection in the intestine → infiltration and activation of macrophages → secretion of inflammatory mediators by macrophages → leaky blood vessels in the intestinal mucosa → protein loss into the intestine → low protein level in blood → reduced oncotic pressure in blood → edema within tissues → swelling of the submandibular tissue. In this example, Mycobacterium paratuberculosis is the cause, paratuberculosis (Johne’s disease) is the name of the disease, granulomatous inflammation is the pathologic process, submandibular edema is the lesion, and swelling of the submandibular tissue is the clinical sign. - Multifocal pulmonary abscessation in a feedlot steer might have the following pathogenesis: carbohydrate over-feeding → rumen bacteria metabolize carbohydrate → rumen acidosis → overgrowth of Fusobacterium and damage to rumen mucosa → entry of Fusobacterium into the portal bloodstream → hepatic abscess formation → erosion into vena cava → embolic showering of bacteria/debris into lung → multifocal abscesses in lung. In this example, excessive carbohydrate ingestion is a cause, “grain overload” is the name of the disease, and inflammation is a pathologic process.

- Dogs with ACTH-secreting pituitary adenomas develop enlarged bronze-coloured livers, with the following pathogenesis: ACTH-secreting pituitary tumour → increased cortisol production by adrenal cortex (hyperadrenocorticism) → cortisol induces glycogen accumulation in hepatocytes → liver enlargement and bronze colour. In this example, the cause of the pituitary tumour is not known, hyperadrenocorticism is the name of the disease, glycogen accumulation is the pathologic process, and enlarged liver and bronze coloration is the lesion.

Key Takeaway

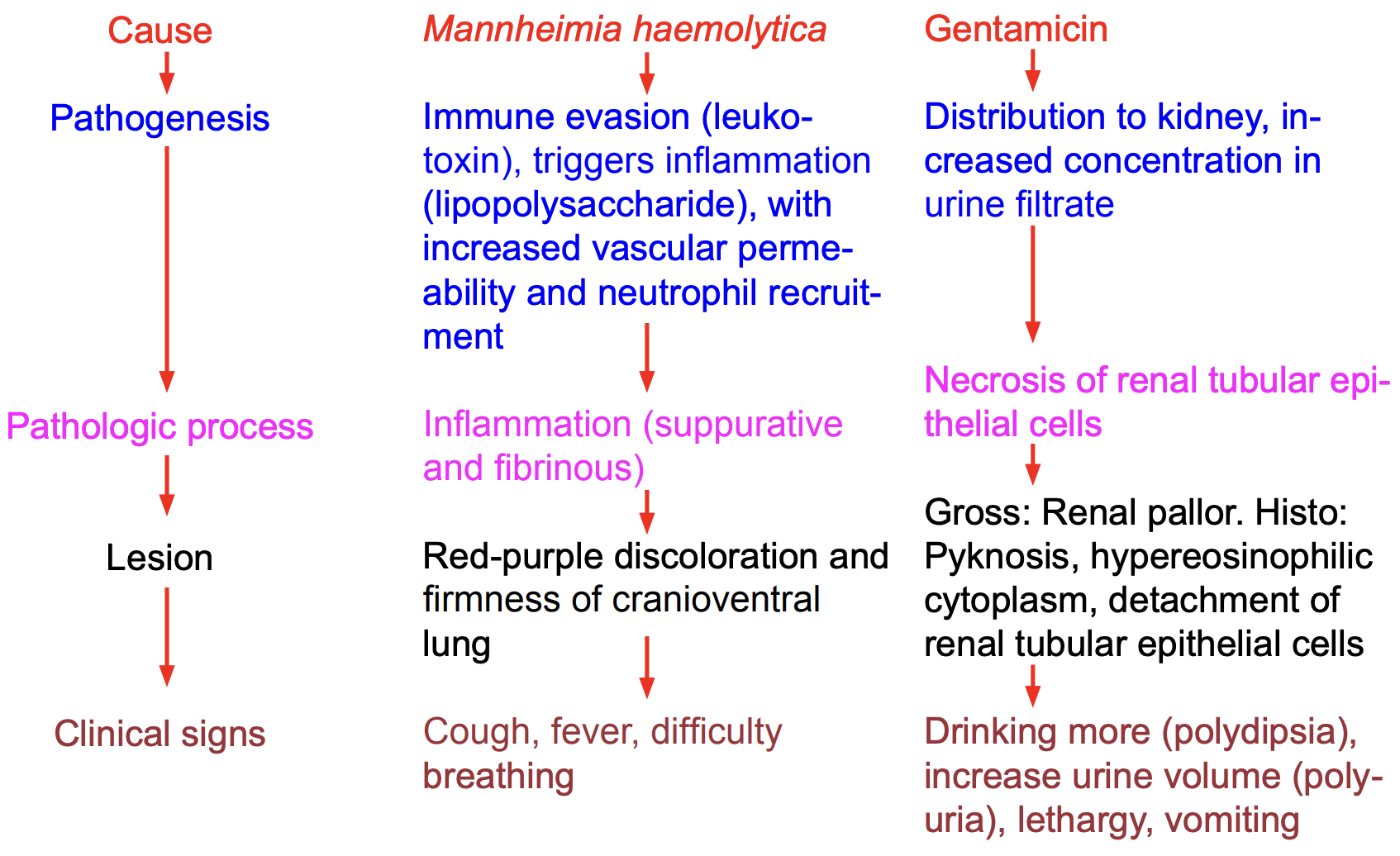

Left: Cause, pathogenesis, pathologic process, lesion and clinical signs are different aspects of a disease, or different ways to think about or conceptualize a disease.

Middle: in bacterial pneumonia of cattle, the cause is Mannheimia haemolytica. This bacterium triggers inflammation which leads to vasodilation and red discoloration of lung tissue, as well as increased vascular permeability and recruitment of neutrophils in the lung that is the reason for the firmness of the affected lung. The systemic (body-wide) inflammation causes fever, and filling of airspaces in the lung with edema and neutrophils results in difficult breathing. This story of how the cause led to the observed changes (red firm lung, and fever and difficulty breathing) is the pathogenesis. The cause is the bacterium, Mannheimia haemolytica. The pathologic process is inflammation (or, neutrophilic inflammation). The lesion is reddening and firmness of the lung. The clinical signs are fever and difficulty breathing.

Right: The antibiotic gentamicin distributes to the kidney and is concentrated in the urine filtrate within the renal tubules. It is toxic to renal tubular epithelial cells, causing necrosis of these cells. The necrosis makes the kidney pale on gross examination, and histologically we can see that the epithelial cells have pyknotic nuclei, hypereosinophilic cytoplasm, and detach from the basement membrane into the lumen of the tubule. Because the tubular epithelium is not functioning well, the tubules cannot resorb water from the urine filtrate, and therefore there is a failure to concentrate the urine, leading to increase volume of voided urine (polyuria) and corresponding increased water intake (polydipsia). Evil substances normally eliminated by the kidney build up in the blood and make the dog feel sick, which we observe clinically as lethargy, reduced appetite and vomiting. The pathogenesis is this tragic tale of how the cause (gentamicin) led to the observed lesions (pale kidney, pyknosis and detachment of renal tubular epithelial cells), and/or the clinical signs (increased urine volume, reduced appetite, etc). Here, the cause is gentamicin, the pathologic process is necrosis, the lesions are the grossly observed paleness of the kidney (and the histologically observed pyknotic nuclei, hypereosinophilic cytoplasm, and cellular detachment), and the clinical signs are increased urine volume and water intake, lethargy, reduced appetite and vomiting. “Feeling sick” would be a symptom, but unfortunately the dog can’t tell us that information directly, only by displaying clinical signs (reduced appetite) that we can observe.

Interpreting gross lesions

With a little training and practice, anyone with knowledge of anatomic terms and appreciation of the normal appearance of tissues should be able to effectively describe lesions. It mainly requires observation and communication. You don’t need veterinary training to be good at description (except for knowing the normal appearance, and the anatomic names). On the other hand, interpretation is where your knowledge of veterinary medicine becomes essential. Description is objective and factual. It should always be correct, even if you don’t know what the lesion represents or what incited it. In contrast, diagnoses or interpretations of a lesion are an educated guess. You will be wrong sometimes. Your interpretation may often be wrong when you are getting started, but hopefully this will become less frequent as you progress through the DVM program, and as you gain experience. But even those with great training and long experience do make incorrect interpretations.

It is often too hard to jump directly from observation and description, to inferences about the cause, functional importance, and expected clinical appearance of the lesion. That is too big of an intellectual leap. And if we do that, we tend to think of only one “answer”, whereas our gross lesion could have several possible causes. So, this is an important point: our diagnostic process (our approach to interpreting lesions) must be done in several steps, so that we can think clearly about each step before moving on to the next.

Sometimes you will be with experts who look at a lesion and immediately give the diagnosis or cause: a red-purple lesion on the right atrium of a dog is hemangiosarcoma (malignant neoplasm forming vascular channels), and red-purple firmness of cranioventral lung in a calf is caused by Mannheimia haemolytica or other related bacteria. But you should recognize that (a) you can’t do this yet in Phases I and II of the DVM program, because you won’t cover specific diseases until Systems Pathology in Phase III, and (b) fixating on a single diagnosis or cause leads to tunnel vision and we fail to consider other possibilities. Occasionally, a red-purple lesion on the right atrium is an infarct or atrial torsion. Maybe that cranioventral lung lesion is aspiration pneumonia instead of Mannheimia haemolytica; these two diseases have very different implications when thinking about how the pneumonia developed and its significance to the surviving animals in the group. Vet students dream that some day they too will be able to immediately make diagnoses and recognize the cause in all of their patients, but this is a poisonous dream: you might achieve that state for clinical scenarios that you very frequently encounter, but even then you will commit errors in some of your cases if you only consider your top-ranked possibility. And, this approach will always fail for cases with non-classical presentations, incomplete information, or concurrent diseases; such cases are common and require a more methodical and systematic approach. It’s the difference between 3D printing where the final shape is known, and revealing an ancient skeleton in a sedimentary rock. In diagnostic pathology, you don’t know the final form (diagnosis) at the beginning of the process, so you have to gradually chisel away the sand to uncover the truth.

So, we break the diagnostic process into several steps:

- Observe and describe the lesions. Only consider the observation of the lesion, the objective facts. No interpretation or diagnosis at this stage.

- Interpret the lesions, based only on the morphology of the lesion in the organ. For now, ignore what you know about the clinical features of the case, and ignore what you know about common causes of disease in different species. This first step is just listening to what the lesion in the tissue is telling us about the nature of the disease.

(a) Infer the likely pathologic process(es)

(b) Construct a morphologic diagnosis

(c) For each the likely pathologic processes, consider possible causes - Refine the lesion interpretation based on clinical features of the case and and knowledge of diseases.

{{This step requires knowledge of diseases and clinical judgement, that you won’t developed until later in the DVM program. In phase I and II general pathology labs, we can only take the diagnostic process so far, but the subsequent steps will come with time}}

(We interpret the lesion morphology first and then refine this interpretation based on knowledge of information from the clinical history, so that the clinical features do not bias our interpretation of the lesion morphology. It is VERY EASY for this to happen. Pathology interpretation can be quite subjective, and difficult when you are getting started, so it is easy to imagine that you are seeing “what should be present” with the most likely clinical diagnosis. I have seen students describe a generalized multifocal pattern of lung abscesses as cranioventral pneumonia, because they really want it to cranioventral bacterial bronchopneumonia … and I don’t think they believed me that the lesion was really random multifocal until we found the right AV valve endocarditis that showered to the lung. Don’t let the clinical history incorrectly bias your interpretation of the lesions in the organ. Intrepret the lesions first, and then subsequently consider the clinical aspects of the case and how they contribute to or refine the interpretation. - Conduct additional investigations to further refine the diagnosis: laboratory (eg., histopathology, or PCR testing for a virus, or measuring a hormone concentration in blood), clinical investigations (a chest radiograph to find the primary tumour in the lung that metastasized to the digit you are examining), or acquire additional clinical history (now that you mention it, we did notice that the cat ate some lilies, the day before the onset of kidney disease).

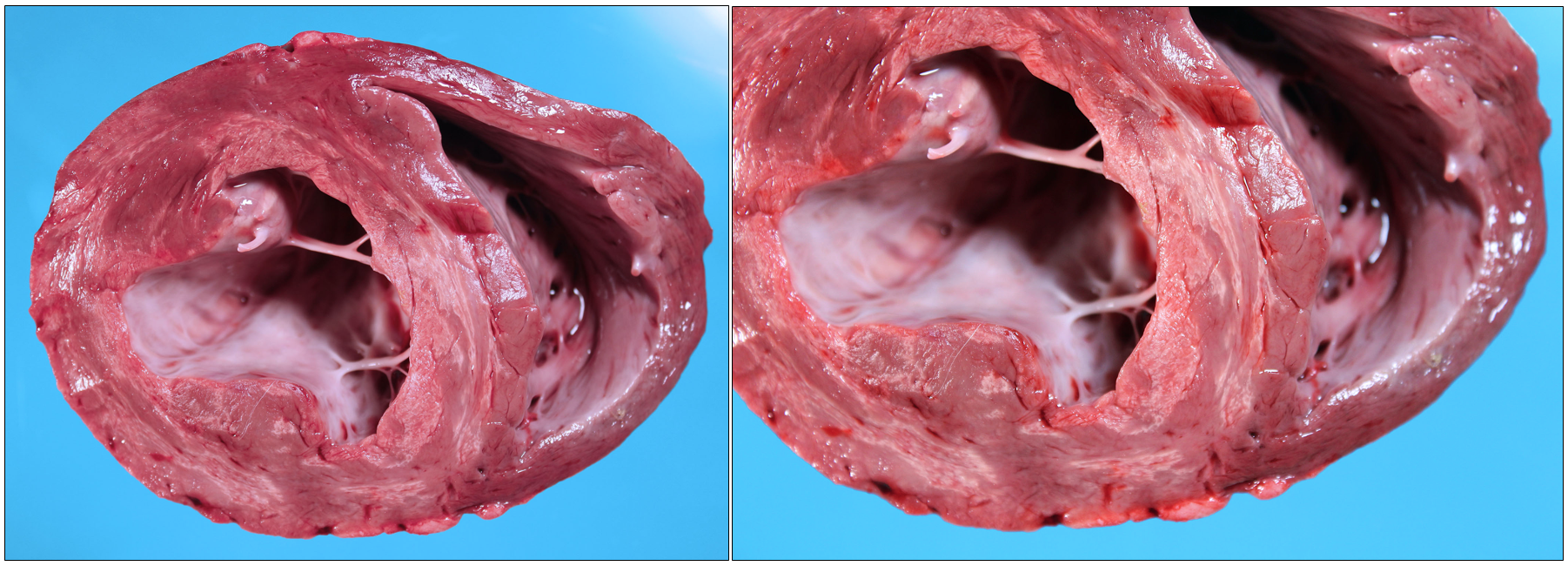

Description: In the left ventricular free wall (left of the image) and interventricular septum, the myocardium contains well-demarcated white coalescing streaks that are flat (not bulging), have the same texture and strength as the unaffected myocardium, and affect ∼25% of the tissue. Lesions tend to affect the subendocardial myocardium, and spare the mid-portion and subepicardial parts of the myocardium. The right ventricular free wall is unaffected.

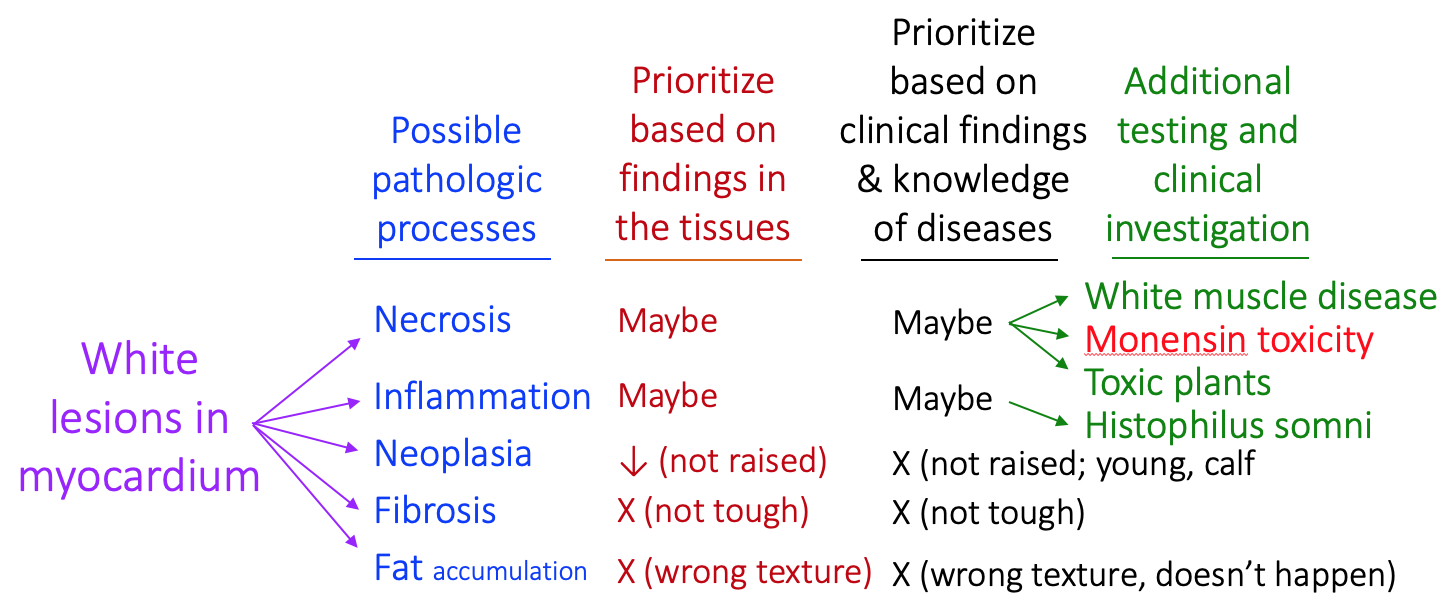

The following table outlines the diagnostic process using the numbering in the list provided above, and font colours correspond to the table below.

1: Interpret the lesions; infer the likely pathologic process(es). The possible pathologic processes that can cause pale lesions in the myocardium include necrosis, inflammation, neoplasia, fibrosis, and fat accumulation. We can prioritize these based on our description of the lesion in the myocardium, as follows. Fat accumulation is unlikely because the lesions are not soft and greasy, and fibrosis less likely because the lesion is not tough. Neoplasia is also placed lower on the list, because neoplasms are usually raised and nodular, rather than forming flat (non-raised) streaks. So, necrosis and inflammation are our most likely pathologic processes. A morphologic diagnosis at this stage could be “severe patchy necrosis of the subendocardial myocardium of the left ventricle”.

2: Refine the lesion interpretation based on knowledge of the clinical features of the case and knowledge of diseases. {{This step requires knowledge of diseases and clinical judgement, that you won’t developed until later in the DVM program.}} Myocardial neoplasia is unlikely based on the lesion morphology, and is also unlikely in a young calf. Myocardial fibrosis is plausible based on the clinical history but not supported by the lesion morphology. Fat accumulation is unlikely based on lesion morphology, and we don’t know diseases of calves that would do this. Myocardial necrosis or myocardial inflammation (myocarditis) are plausible based on the clinical history. Myocardial necrosis could be caused by white muscle disease (vitamin E / selenium deficiency) or toxicity such as monensin feed additive. Myocardial inflammation (myocarditis) could be caused by blood-borne bacterial infection such as Histophilius somni.

3. Conduct additional investigations to further refine the diagnosis. We can do a bacterial culture of the myocardium to look for H. somni and other bacteria, but there is no growth … and the histologic lesions are of necrosis not inflammation. These are housed cattle (no pasture) and they were given vitamin E / selenium injections at birth, so white muscle disease is less likely. Toxic plants are less likely in housed calves, and we don’t have toxic plants known to cause myocardial necrosis in this geographic area. With further discussion, the owner tells us that the calves recently started on a new batch of feed. Laboratory testing showed higher than expected levels of monensin in this new feed, and in the kidney. So, our final diagnosis is monensin toxicity. {{Disclosure: there was actually no follow-up testing done on this case, so the latter parts are fictitious to illustrate the diagnostic process))

For the above case of myocardial necrosis, if we had made a quick diagnosis based on the initial appearance, we might have thought this was myocarditis, or white muscle disease. Going through the step-wise, methodical, systematic process allows us to consider different pathologic processes, and use our observations to prioritize which are most plausible. This served as a basis for thinking of different specific causes, and then we conducted specific targeted testing and collected specific new clinical information that allowed us to identify the true cause. Next, we can consider these steps in the diagnostic process in more detail.

infer the pathologic process

Pathologic process is the change occurring within the tissue that is induced by the causative agent, and explains the observed lesions. The pathologic process is not a real tangible thing, it is mainly a concept that humans have created to explain what is happening in tissues. The pathologic process results in development of a lesion. Lesions are real things that can be observed and measured. For example, inflammation is a pathologic process, and the lesion is accumulation of fluid (water) and neutrophils within the tissue. Neoplasia is a pathologic process, and the lesion is expansion of the tissue by cells of uniform appearance and cell type. Hypertrophy is the pathologic process by which muscle cells bulk up by increasing their number of contractile myofilaments, and the observed lesion is increased size of the cells or of the tissue.

Some pathologic processes are as follows. It can be helpful to remember that pathologic processes include the topics in the General Pathology course (forms of cell death, cellular adaptations, vascular changes, inflammation, neoplasia).

-

-

- Neoplasia (or if possible, indicate carcinoma, adenoma, sarcoma, lymphoma, osteosarcoma, etc)

- Inflammation (indicate where possible: fibrinous, granulomatous, neutrophilic/ suppurative, etc)

- Fibrosis

- Necrosis, ischemia, infarct, infarction

- Edema, hemorrhage

- Atrophy, hypertrophy, hyperplasia, dysplasia, metaplasia

- Aplasia, hypoplasia, atrophy

- Mineralization, lipidosis, melanosis

- Thrombosis, embolism

- Congestion, hyperemia, hemorrhage

-

We infer the pathologic process based on our description of the lesions. Detailed guidance on how to use descriptive findings to infer the pathologic process are given in “Chapter 3: Description as a basis for interpretation”. This is an important first step in our diagnostic process, and is the basis for the next step: constructing a morphologic diagnosis.

Construct a morphologic daignosis

The morphologic diagnosis is an initial interpretation based only on the morphology of the lesions. Your observations and description reflect the facts of the lesion. The morphologic diagnosis is the first stage of interpreting or making inferences about the nature of those lesions.

Morphologic diagnoses are a tool for problem solving. It is too intellectually difficult to jump from description to diagnosis. The morphologic diagnosis is a middle step that helps us to make a preliminary interpretation, and to consider all the various possibilities. Therefore, it is a more rigorous approach to determine the cause, pathogenesis, functional importance, and clinical manifestations.

Morphologic diagnoses may include 5 elements. Sometimes, some of these elements are not applicable or cannot be determined, so they are omitted. For example, in the myocardial lesion discussed above, it is impossible to estimate the duration of the lesion based on this gross appearance, so this was omitted from the morphologic diagnosis. Similarly, for cancer (neoplasia), we often omit the severity because it often isn’t sensible to interpret a lesions as “mild neoplasia” or “severe neoplasia”.

- Severity: a subjective estimate of the expected significance or extent of the lesion. Mild, moderate or severe.

- Duration: acute, subacute or chronic.

- Distribution of lesions: multifocal, diffuse, localized, generalized, etc.

- Pathologic process: inflammation, necrosis, edema, etc.

- Organ or tissue, or component of the tissue affected: hepatic, small intestinal mucosal.

Components of the morphologic diagnosis

- Organ or tissue affected

- Severity: mild, moderate, severe

- Time: acute, subacute, chronic

- Distribution: diffuse, multifocal…

- Pathologic process: inflammation, neoplasia, necrosis…

+ a modifier: fibrinous, granulomatous, necrotizing, proliferative

Here are some details about the five elements of a morphologic diagnosis.

Severity: This is your estimate of the lesion’s severity. It is usually stated as mild, moderate, severe. These terms are subjective (what you call severe, another could call moderate), but they communicate your own interpretation of the lesion’s importance or extent. Severity can reflect how extensive the lesion is within the organ, or how important the lesion is for the animal’s health. Sometimes these two meanings are in conflict: it seems inappropriate to call a tiny lesion in the brainstem “mild” if it caused death. Similarly, we wouldn’t call a visually dramatic lesion “severe” if it were present throughout an organ but we knew it was functionally unimportant or would not result in any illness.

Duration: Acute, subacute and chronic are not precisely defined with respect to the number of days they have been occurring.

We don’t state the duration in cases of neoplasia because it is not sensible to do so. In cancer, we can’t really estimate when the disease started.

- Peracute: appearing very suddenly without prior clinical signs of illness.

- Acute: a disease that has developed so recently that it hasn’t yet had a chance to resolve (e.g., less than 4-7 days). We might recognize an acute lesion by the presence of fibrin that hasn’t yet organized into fibrous tissue, or acute vascular changes such as hyperemia.

- Subacute: between acute and chronic.

- Chronic: persistent or recurrent or relapsing for a long time, or fails to heal or fails to respond to treatment over a long time. Chronic lesions are those that have had adequate time to spontaneously resolve but have not done so. Some might call a disease chronic if it lasts for longer than 21 days; others might require it to last for more than 3 months; this probably depends on the specific illness. We might recognize an acute lesion by the presence of maturing fibrous tissue, or histologically by large numbers of lymphocytes and plasma cells, or attempts at regeneration of the tissue.

- Chronic-active: this term is used for chronic lesions that have evidence of an active ongoing disease process. For example, a ulcer in the stomach mucosa or in the skin could be called chronic-active if it had fibrin and neutrophils on the surface, and extensive scarring in the deeper part of the tissue.

Distribution: see the earlier notes. Words to describe distribution include generalized vs localized, diffuse vs multifocal, localized, zonal, etc.

Pathologic process: see the previous section.

Tissue: this can take the form of a:

- Noun: liver, skin, kidney cortex, grey matter of brain

- Adjective: hepatic, cutaneous, renal cortical

- Greek prefix: hepa- (eg., hepatitis), nephro- (eg., nephropathy), encephalo- (eg., polioencephalitis)

A few special rules apply:

a) Inflammatory lesions often mention the the organ and inflammation (“-itis”) in a single word: hepatitis, dermatitis and glomerulonephritis for inflammation of the liver, skin and renal glomeruli, respectively. Pneumonia is inflammation of the lung. Communication is the key: keep it simple if the Latin translation is too complex to permit useful communication—inflammation of the lacrimal gland may be more effective than sialodacryoadenitis, if your audience doesn’t know this word.

b) For neoplasms, the morphologic diagnosis is typically only 2-3 words: the organ or tissue involved (as an adjective or prefix), the type of neoplasm (adenoma, carcinoma, sarcoma etc.), and the distribution which can include “metastatic” or “invasive” if relevant. Examples include dermal sebaceous adenoma, invasive hepatic carcinoma, multifocal splenic hemangiosarcoma, and pulmonary metastases of urothelial carcinoma.

c) Sometimes, the severity or duration of the lesion cannot be determined or is irrelevant. In those circumstances, these components may be omitted. Two examples:

- The severity and duration might not be given for neoplasms, because even a small tumour could be fatal if it metastasized or effaced a vital structure, and the duration usually cannot be determined.

- If there is no evidence of fibrosis, it is often impossible to determine if an inflammatory lesion is acute or chronic. In these circumstances, omit the duration. On the other hand, when it can be determined, this information is critical to accurately communicate the disease process (e.g. severe acute fibrinous and suppurative bronchopneumonia).

As mentioned above, the morphologic diagnosis is a useful tool in the diagnostic process. It is an initial interpretation that allows us to collect our ideas about the case in a tidy package. Once we have made that initial concise and structured interpretation, then we can use that as a platform to think about possible causes, how the disease might have developed, what effect it may have on organ function, and how this lesion might explain the observed clinical appearance of the case.

Interpret the likely cause, pathogenesis, histologic correlates, functional importance, and anticipated clinical appearance

This step involves integration of the above observations and interpretations with additional case information (signalment, clinical signs, number of animals affected, response to treatment, etc). Here you will use all of your knowledge gained from this and other courses, your experience, and your insights. Synthesizing all of this information, we can try to make inferences about the likely cause(s), the pathogenesis (i.e., how the disease might have developed, which can give clues about possible causes), the impact of the lesion on proper function of the organ, and the clinical appearance that might be anticipated as a result of this lesion.

It is a serious mistake to jump directly from observation to cause. We encourage a step-wise approach to case interpretation: find the thing that is abnormal, then describe it objectively, then think about the pathologic process and other components of the morphologic diagnosis, and then make the above inferences. This is a more rigorous approach to diagnosis, because you can consider all of the various diagnostic possibilities (i.e., differential diagnoses) instead of a tunnel-vision focus on the first disease you happen to think of.

It doesn’t always work this way: experienced practitioners or pathologists may look at a puppy with enteritis or a cat with an intestinal tumour and immediately say “That looks like parvoviral enteritis” or “That lesion is intestinal lymphoma”. They can do this either because they are going though this same step-wise process quickly in their minds, or because they have seen the lesions before and are recognizing the pattern. In the latter case, it would be a mistake to stop at that point. After making a quick tentative diagnosis, always revisit the specimen and go through the process of description, interpretation, then consideration of various diseases or causes. When we leap to a diagnosis, we commonly overlook other possibilities and ignore clues that point to a different conclusion. You are Sherlock Holmes, or Hercule Poirot. Investigate the case methodically: consider all of the various possibilities, eliminate or de-prioritize some diagnoses based on observation of the lesions in the tissue, then rule out other diagnoses based on other information you know about the case, and finally do additional laboratory testing, additional clinical investigation, or obtain additional clinical history so that you can confirm or refute the most likely differential diagnoses and reliably arrive at the correct diagnosis.

This section described the diagnostic approach used in pathology, for evaluation of lesions in tissues. But please recognize that the very same principles apply to clinical diagnostic evaluation of cases, although the specific steps and the goals are a little different (for example, “subjective, objective, assessment, plan”).