5 Atlas of some artefacts and incidental findings

This section of the notes is intended to illustrate some tissue changes that catch our attention during a postmortem examination, but do not represent the cause of death. These include artefacts (changes that occur in tissues after death), and common incidental findings (lesions in tissues that develop prior to death, but are not of clinical or functional consequence and therefore are not relevant to the cause of death.

You are not expected to memorize these. Recognition of artefacts is a learning objective of the course, but you will not be tested directly on your knowledge of artefacts and incidental findings. Nevertheless, this knowledge will be handy so that these unimportant tissue changes do not distract you from identifying the “real” important lesion within the tissue, during an exam or in real life.

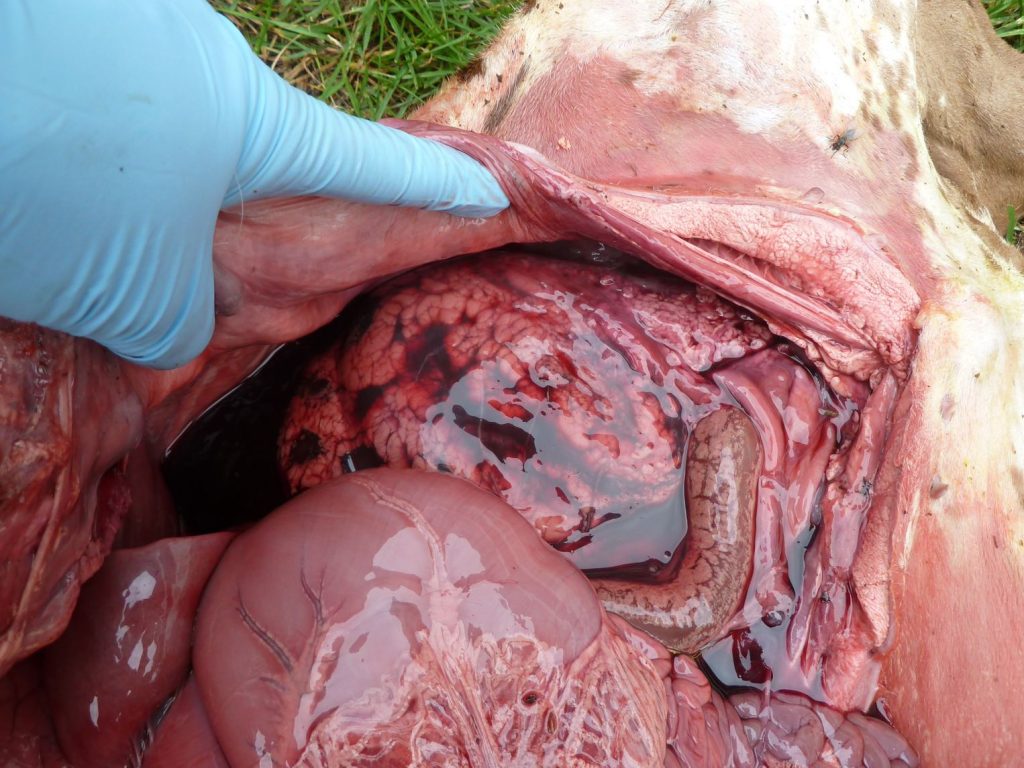

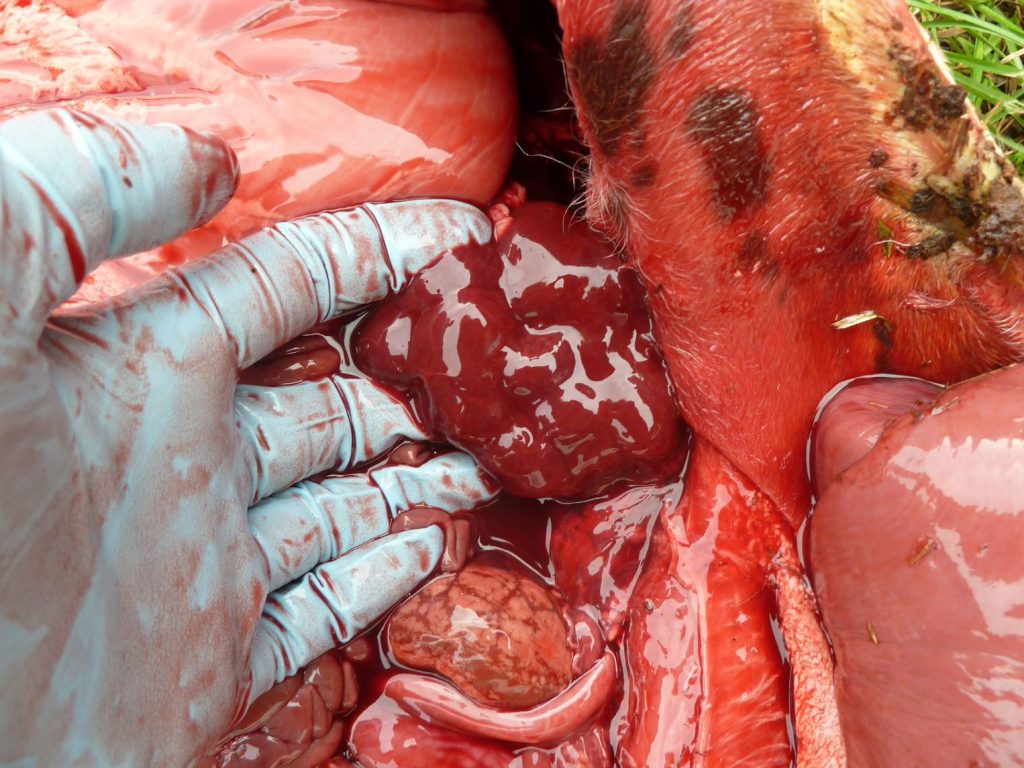

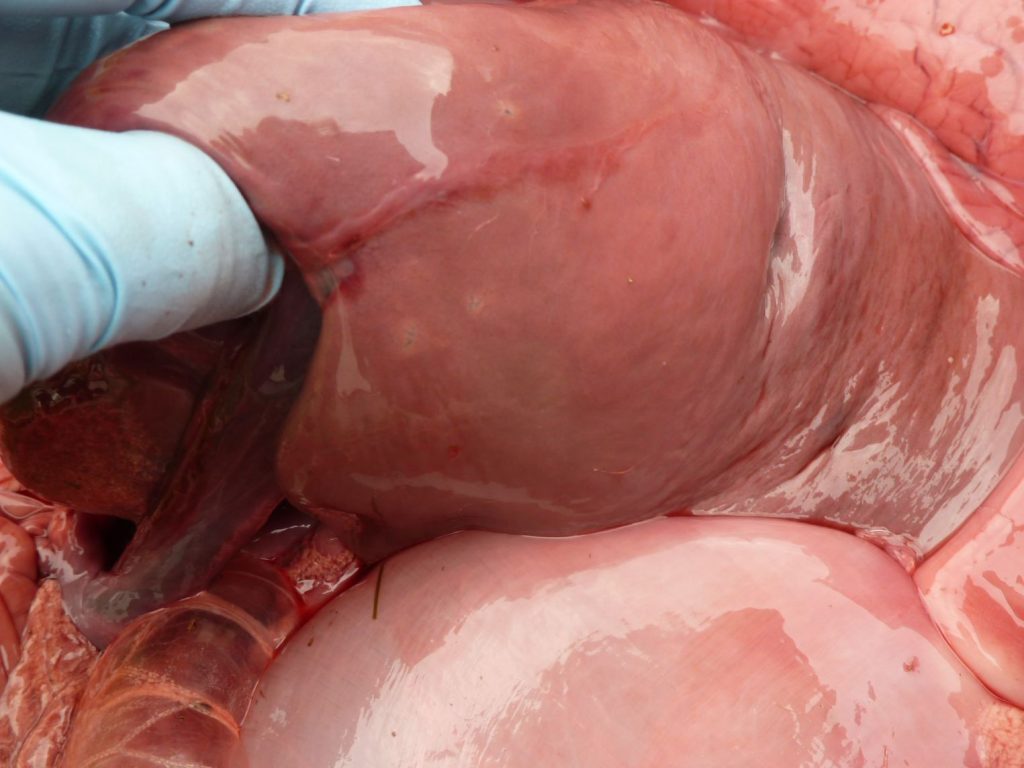

3 above images: a fine example of autolysis in a bovine fetus. This fetus would not have a putrid smell (but instead has the stale smell of death), because this is autolysis rather than putrefaction.

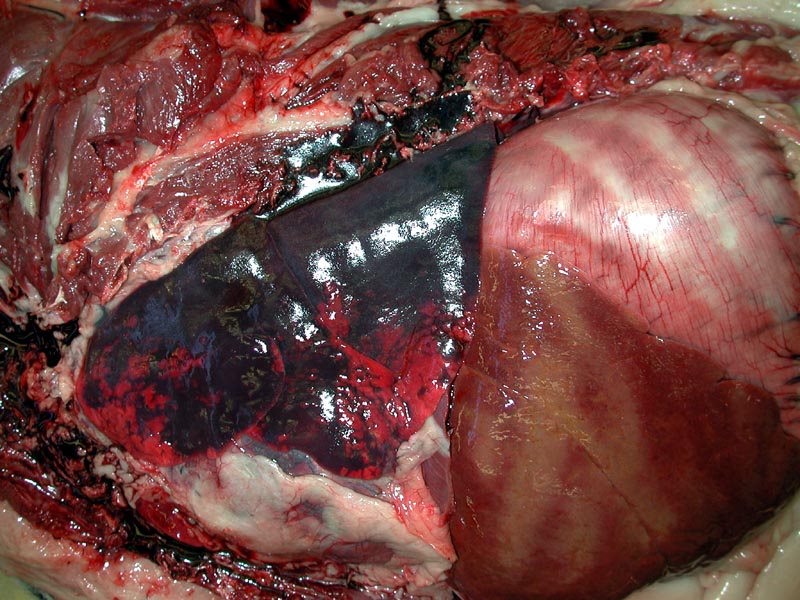

First image: The opened abdomen filled with red fluid, and all tissues are stained red. This represents imbibition of hemoglobin, when erythrocytes lyse after death.

Second image: The normally lobulated bovine kidney is liquefying due to self-digestion.

Third image: The liver is diffuse pale and would be friable.

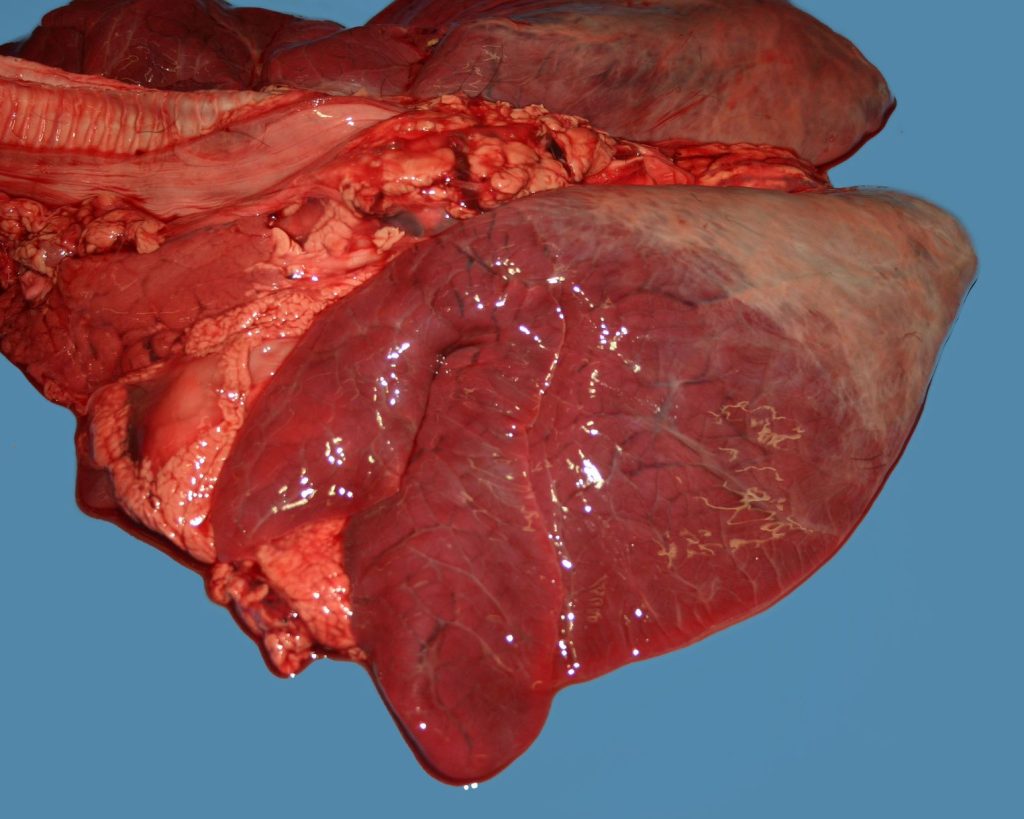

3 above images: Normal lung (cat: first; dogs: second and third). These lungs have varying degrees of patchy or diffuse reddening, due to redistribution of venous blood to the lungs after death. Normal fresh lung has the salmon- pink colour visible in the left panel. Deep and purposeful palpation is the key to distinguishing these changes from pneumonia: all three of these lungs have the pleasing soft and spongy texture of normal lung, whereas lungs with pneumonia would be more firm.

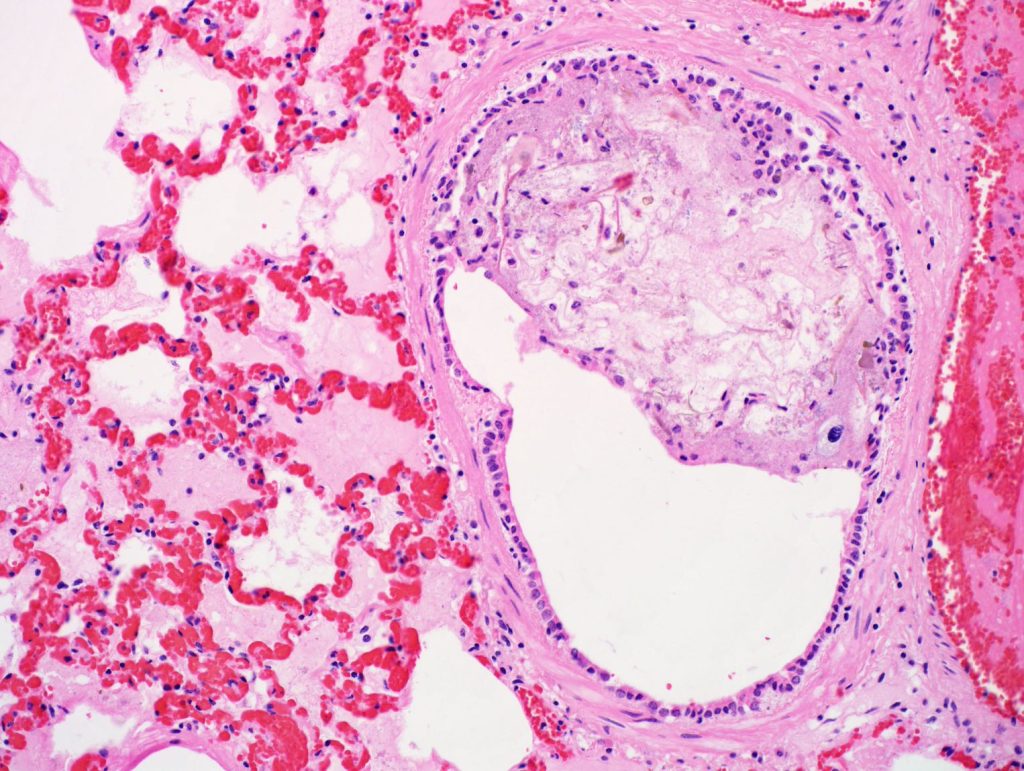

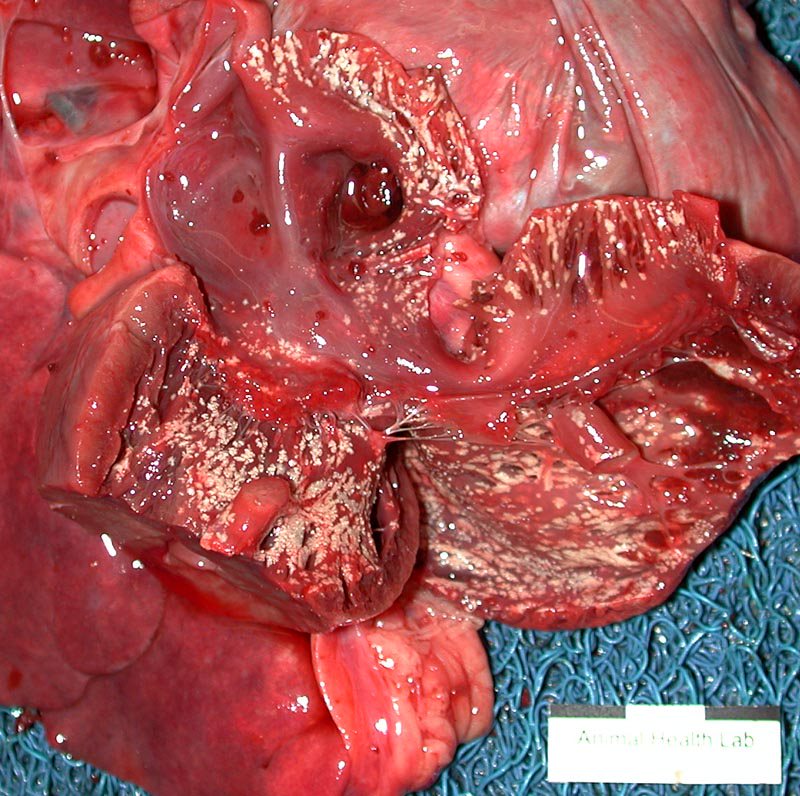

Above: Regurgitation of rumen content with aspiration into the bronchi. This is a relatively common incidental finding in cows. The regurgitation and aspiration occur in the final moments of life. In contrast to antemortem aspiration that causes pneumonia, there is no reddening of the bronchial mucosa, and histopathology (first image) shows plant material in the airways without any associated inflammatory cells.

Above: Lung, calf. Aspiration of blood into the bronchi is infrequently seen as a result of euthanasia by gunshot or captive bolt.

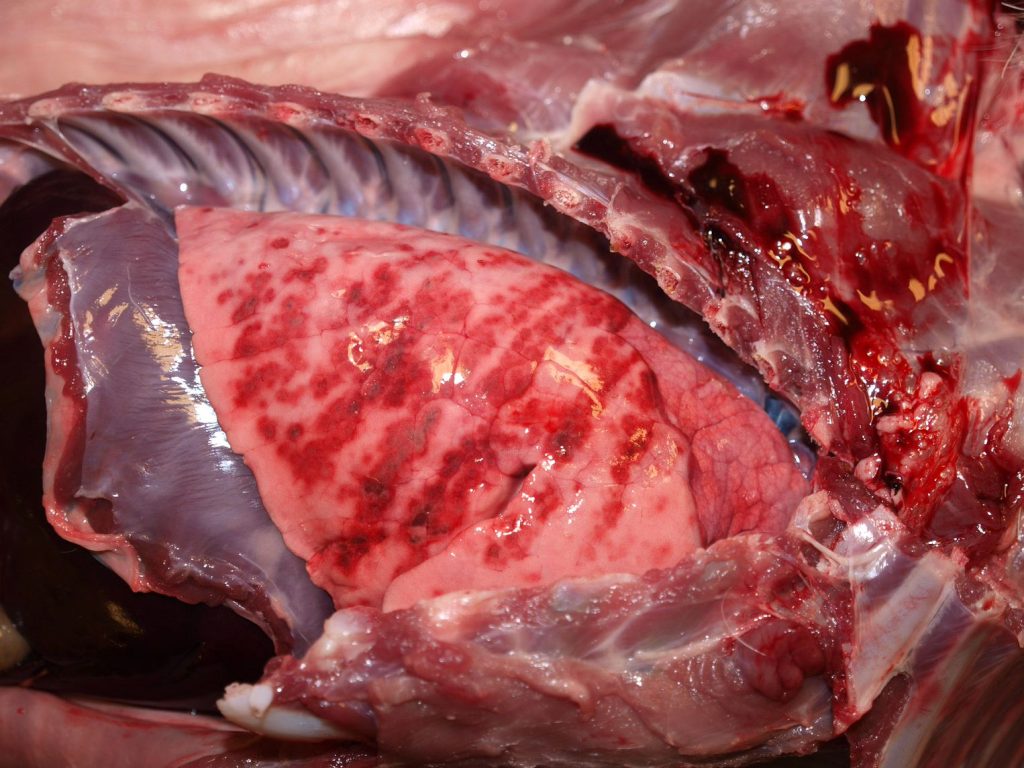

Above: The multifocal hemorrhages in the lung of this pig were thought to have occurred at the time of slaughter. This is a very uncommon artefact, and we would also consider antemortem hemorrhages due to sepsis, thrombocytopenia, vasculitis, etc.

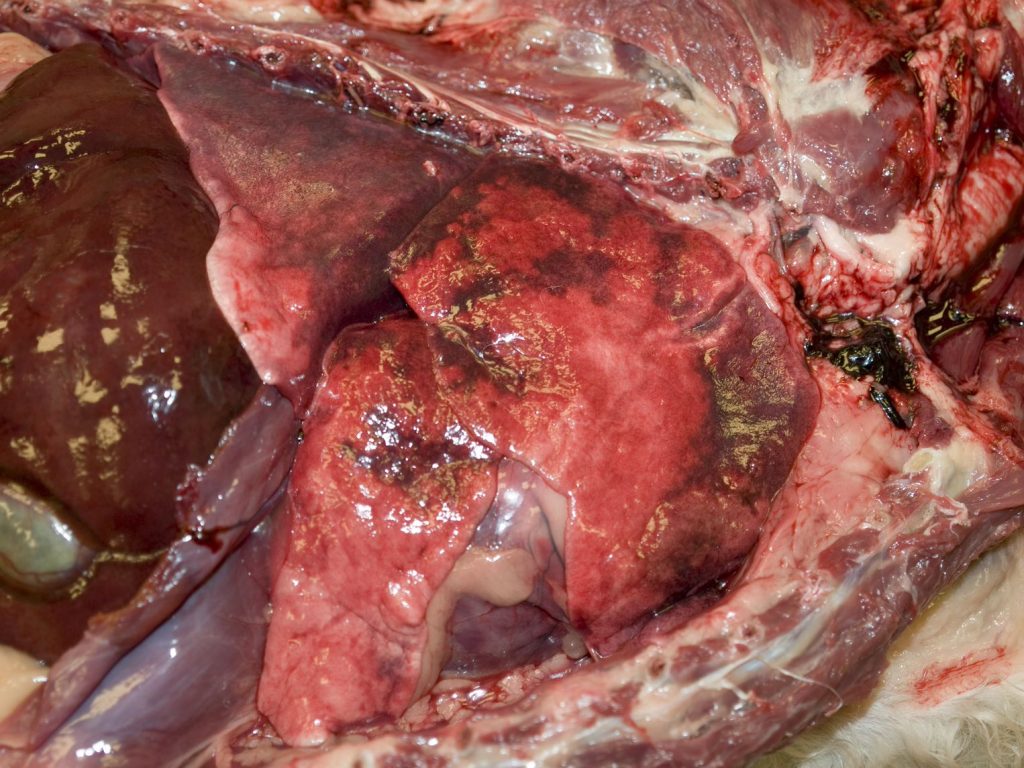

Above: Fetal atelectasis, bovine fetus. The lung is deep red and collapsed because the calf has never breathed. The texture is soft, although lacks the sponginess of air-filled lung. It is not firm like a lung with pneumonia. Opacity of the dorso-caudal pleura is normal in cattle.

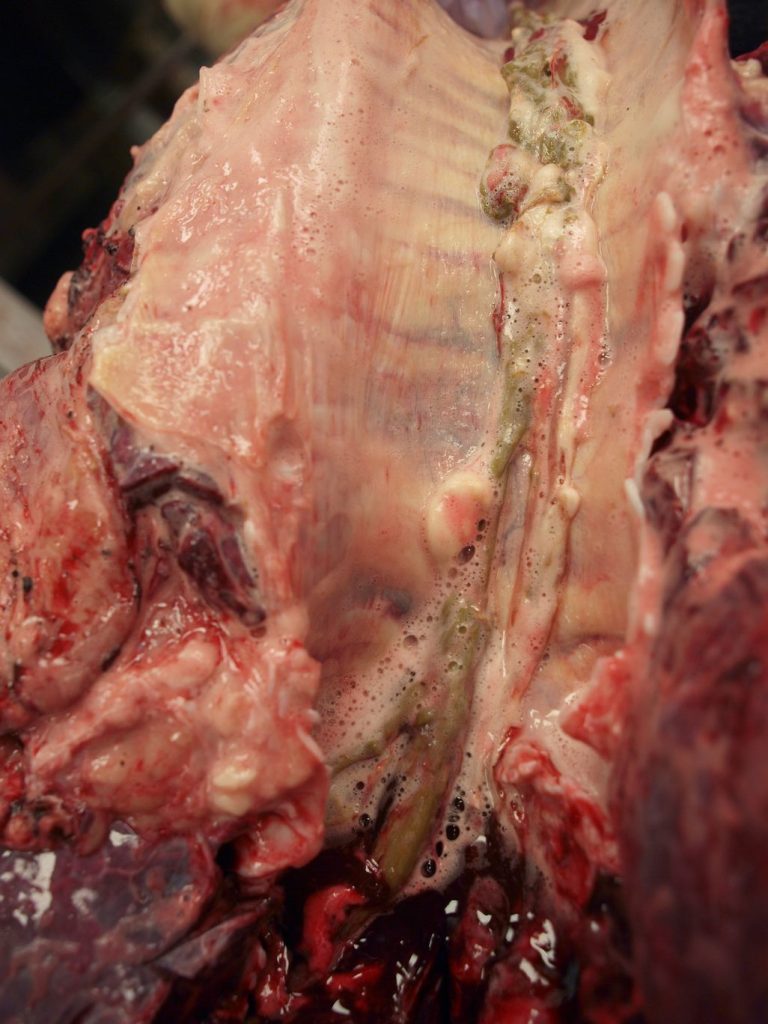

Above: Fibrous adhesions of the lung to the ribs (i.e. the visceral to the parietal pleura) is a common incidental finding in cattle and pigs. This results from prior pneumonia or pleuritis, but it is inactive and should not be considered as a cause of death.

Above: Barbiturate deposition in the endocardium of the right heart, dog. This is a very frequent artefact in small animals that were euthanized by intravenous administration of an excessively large amount of barbiturate. It affects the right atrium and ventricle, and has a characteristic finely gritty texture. In these cases, the blood filling the lumen typically forms a brown slime that fails to coagulate.

The same lesions are seen in the pericardium or pleura of animals euthanized by intracardiac injection. Hemopericardium can also be present in animals euthanized by the intracardiac route.

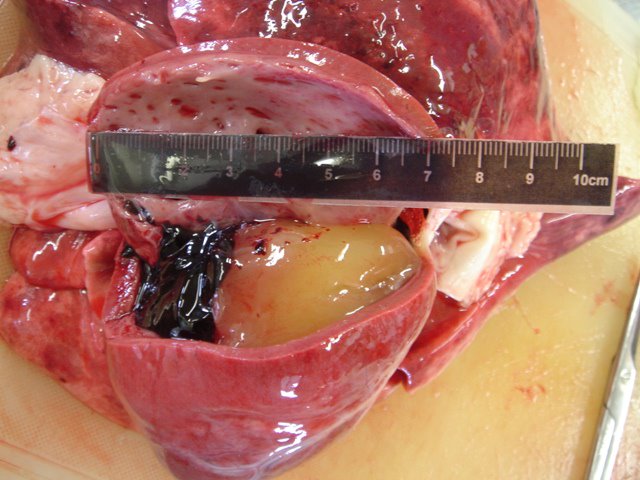

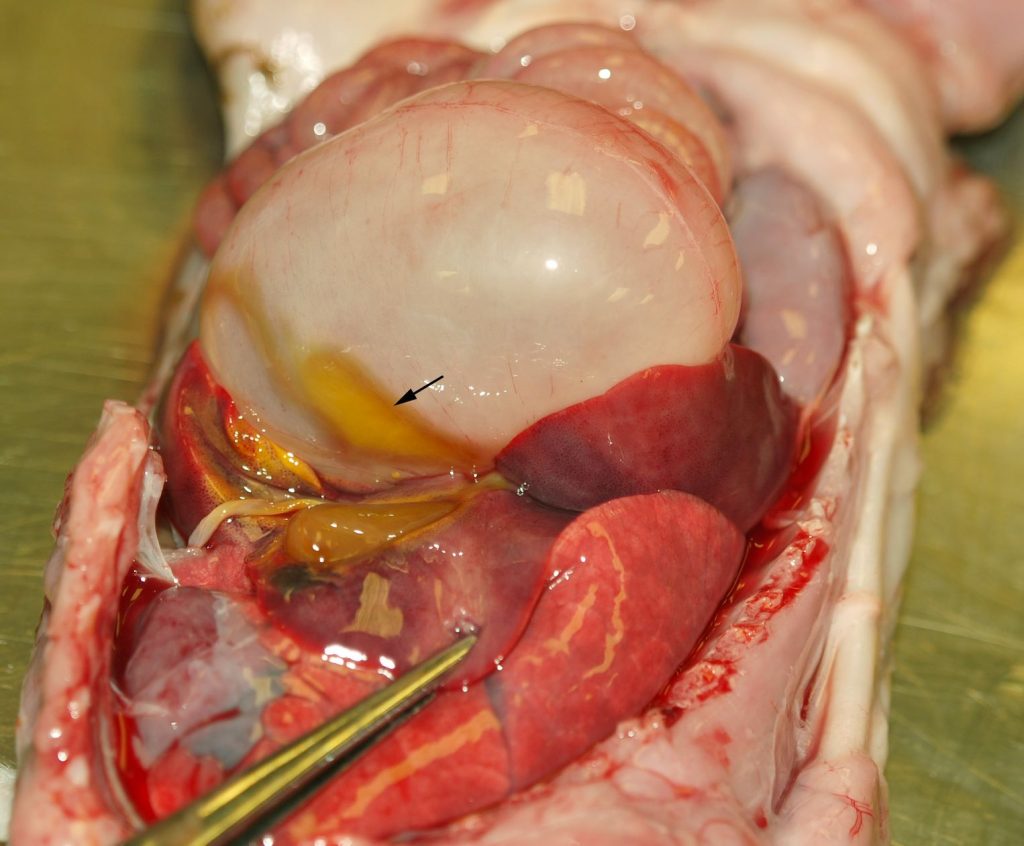

Above: “Chicken fat clot”, dog heart. The yellow material within the ventricle is coagulated serum that has separated from the erythrocytes by gravity, after death. It is the same process that occurs in a red-top serum tube, where centrifugation separates the serum and the erythrocytes. The material looks a bit like cooled chicken fat in a pan, but it is really serum! It is of no diagnostic significance.

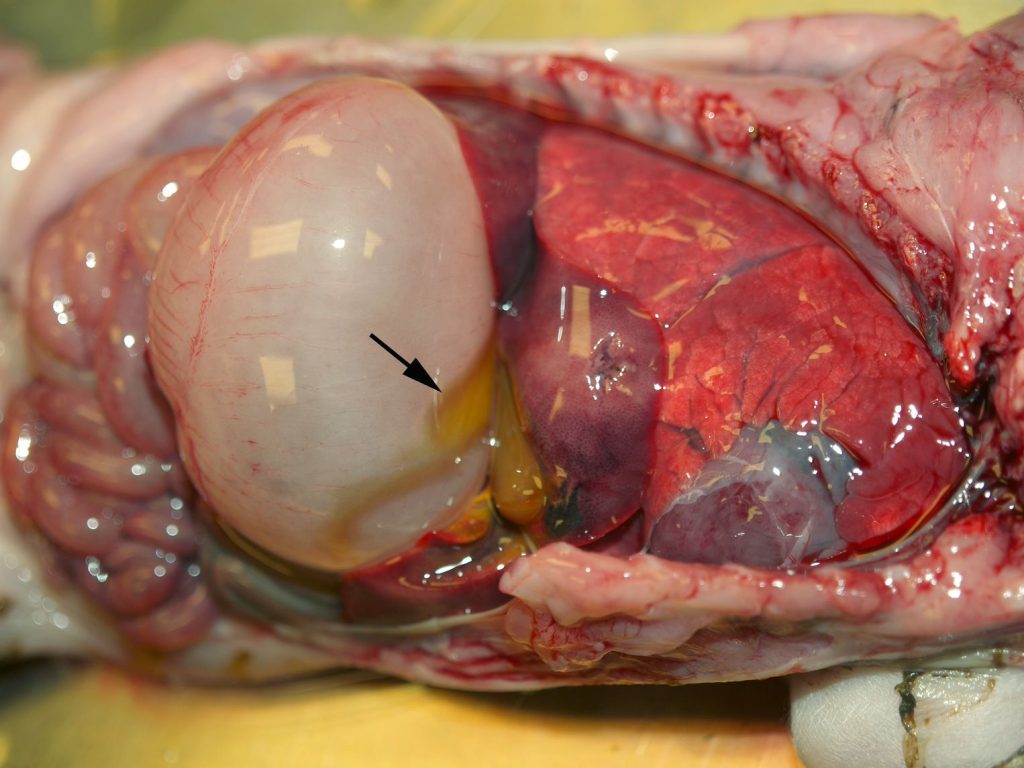

Above: Yellow-green discoloration of the viscera that lie against the gall bladder. As the gall bladder mucosa becomes permeable after death, the adjacent tissues become stained by the bile. It is a common postmortem artefect. Also, note the distention of the stomach by gas (tympany), due to postmortem gas production by bacteria. After we die, our flora will survive and continue their metabolic activities for a while, until they are out-competed by the saprophytes that turn us to dust.

Above: Cat liver. The pallor is due to lipido- sis, a real antemortem lesion. The green- black discoloration of the liver tissue at lower right results from imbibition of bile pigments from the adjacent gall bladder.

Above: olive-brown discoloration of an auto- lysed equine small intestine. The segment at the top of the photo is opened, showing the mucosa that is liquefying due to autolysis.

xxxxxxxx