11. Corporations and Politics: After Citizens United

Corporate Influence on Politics

Corporations today exert a considerable (and occasionally overwhelming) influence on global politics. In some countries, the influence of corporations on government is so great as to give rise to the suspicion that the government is actually controlled by corporations. Even in those countries that strictly limit corporate influence on political campaigns, the corporate sector can still play an important role in the development of governmental policies through sophisticated, high-level lobbying. In this chapter we ask, how much of this corporate influence is acceptable? We will also explore the following related questions: How can corporate influence be controlled? What is the appropriate level of corporate participation in the drafting of laws and regulations? Should corporations be allowed to contribute freely to political campaigns? What is the role of foreign and multinational corporations? Should they also be allowed to influence domestic politics?

Although we will focus on corporate influence, let us note at the outset that they are not the only source of money in politics; wealthy individuals, unions, and other participants in the electoral process also contribute significant funds and resources to campaigns. In the United States, as in most other industrialized democracies, electoral campaigns have become increasingly expensive despite attempts to limit allowable expenditures.

Given the importance of the issue, it is not surprising that a storm of controversy arose over a US Supreme Court’s ruling in 2010 that government limits on corporate spending in political campaigns violated the First Amendment right to freedom of speech. In the view of an openly dismayed President Barack Obama, the Court’s decision in Citizens United v. Federal Elections Commission “reversed a century of law to open the floodgates for special interests—including foreign corporations—to spend without limit in our elections.”1

The validity of President Obama’s objection to Citizen United has been hotly contested, and it will provide us with a focal point for our discussion: Is it true that corporations have achieved excessive influence over national politics? Are corporations entitled to be treated as “persons” when it comes to freedom of speech?

A Basic Distinction: Private vs. Public Funding of Campaigns

While private election spending in the United States is increasing, the situation around the world is quite diverse. In some countries, expenditures are increasing while elsewhere they are decreasing. A basic distinction in national campaign finance regulations is that some countries allow private support for political campaigns while other countries provide public funds to candidates.

Private Finance

In the United Kingdom there are no limits on corporate or individual giving in the general election, yet total spending on the 2010 general election was down 26 percent from 2005.2 However, in the United Kingdom, the Prime Minister may call for elections at any time within a maximum period, which shortens the total time available for campaigning and explains the need for funds. National elections tend to be more expensive in the United States because they come along at predictable four-year intervals.

In Brazil, it is estimated that $2 billion was spent by parties and candidates in the 2010 presidential election, with nearly 100 percent of total campaign donations coming from corporations.

Public Funding

In countries such as Norway, government funding accounts for up to 74 percent of political campaigns, and political ads are banned from television and radio.

In Canada, candidates are given strict spending limits based on the number of voters in their districts, in order to even the playing field in elections, and private donations (a maximum of $1,200 to any party) are heavily subsidized by public funds paid out through tax credits. Although the price of elections has grown 50 percent in the past decade, Canadians spent just $300 million on the 2008 general election.3

Campaign Finance in the U.S.

US Campaign Finance Law, PACs and Super PACs

“There are two things that are important in politics. The first is money, and I can’t remember what the second one is.”

—Mark Hanna, campaign manager of President McKinley’s successful bid for the Presidency in 1896.

Concern over the influence of money in politics began at an early stage in the life of the United States, with Thomas Jefferson stating in 1816 that he feared it would be necessary to “crush in its birth the aristocracy of our moneyed corporations, which dare already to challenge our government to a trial of strength and bid defiance to the laws of our country.”4

Despite Jefferson’s hopes, the influence of corporations on politics grew substantially in the latter half of the nineteenth century. The presidential elections of 1896 and 1904 left much of the American populace disgusted and convinced that political office in the United States was up for sale. In 1896, the victor in the presidential election, William McKinley, outspent his competitor, the populist William Jennings Bryan, by a factor of 10 to 1. In 1904, the Democratic candidate, Alton Parker, lost the election and complained bitterly afterward that he had been defeated by large insurance companies. Parker challenged the nation to face the reality that corporations were taking over the political process: “The greatest moral question which now confronts us is shall the trusts and corporations be prevented from contributing money to control or aid in controlling elections?”5

President-elect Theodore Roosevelt took the accusation seriously and joined his own voice in the call for control of corporate contributions. In a 1905 address to Congress, Roosevelt called for legislation:

All contributions by corporations to any political committee or for any political purpose should be forbidden by law; directors should not be permitted to use stockholders’ money for such purposes; and, moreover, a prohibition of this kind would be, as far as it went, an effective method of stopping the evils aimed at in corrupt practices acts. Not only should both the National and the several State Legislatures forbid any officer of a corporation from using the money of the corporation in or about any election, but they should also forbid such use of money in connection with any legislation save by the employment of counsel in public manner for distinctly legal services.6

As a result, Congress passed the 1907 Tillman Act, the first US law prohibiting corporations from contributing directly to federal elections. However, it turned out that the law was easy to circumvent. Not only was there no enforcement mechanism or agency, the Tillman Act did not prevent corporate contributions to party primaries, and in many Congressional districts these were even more determinative than the general election. Moreover, the Tillman Act did not prohibit corporate officers from giving money personally to campaigns (the executives were then often reimbursed by bonuses from the corporations). It rapidly became clear that the Tillman Act would only be the beginning of a long and tortuous effort to curtail corporate influence.

After World War II, labor unrest reached a historical high. From 1945–1946, millions of railroad, auto, meatpacking, electric, steel, and coal workers went on strike, protesting falling wages amid rising corporate profits. Corporate fears of powerful labor unions and the perception among politicians that labor unions had communist leanings convinced Congress to pass the Taft–Hartley Act (also known as the Labor Management Relations Act) in 1947, which limited workers’ rights to strike, boycott, and picket. The law also prohibited labor unions from spending money in federal elections and campaigns. As an extension of the Tillman Act of 1907, Taft–Hartley constrained labor unions to raising money for campaign contributions only through so-called political action committees (PACs).

It was not until the 1970s that PACs were firmly regulated by the federal government. With the passing of the Federal Election Campaign Act (FECA) in 1971 (and subsequent Amendments in 1974, 1976, and 1979), the modern campaign finance system was born, along with an independent body to enforce it—the Federal Election Commission (FEC). The new law defined how PACs could operate, set contribution limits, and instituted public financing for presidential elections.7

Until 2010, individuals were limited to $2,500 contributions to PACs, and corporations were strictly banned from donating. However, as we shall see below, the Citizens United case radically altered this landscape, removing all corporate restrictions and giving rise to the so-called Super PAC—a political action committee that can accept unlimited donations from individuals, corporations, and unions, and engage in unlimited spending. The only restriction on Super PACs is that the donors cannot coordinate activities with any candidate or campaign. As we can see below from the satirical commentary by television personality Stephen Colbert on the effectiveness of such a bar on coordination, many felt that Super PACs were in reality little more than funding mechanisms under the control of politicians themselves. It seemed that the efforts to control corporate contributions, begun with the Tillman Act, had finally reached a dead end.

Milestones in Campaign Finance8

- 1907: Passage of the Tillman Act, which banned corporate political contributions to national campaigns.

- 1925: The Federal Corrupt Practices Act increased disclosure requirements and spending limits on general elections.

- 1971: Passage of the Federal Election Campaign Act (FECA), the first comprehensive campaign finance law.

- 1974: Amendments made to the Federal Election Campaign Act: limits on contributions, increased disclosure, creation of the Federal Election Commission (FEC) as a regulatory agency, government funding of presidential campaigns.

- 1976: Buckley v. Valeo: The Supreme Court upheld limits on campaign contributions, but held that spending money to influence elections is protected speech under the First Amendment.

- 1978: First National Bank of Boston v. Bellotti: The Supreme Court upheld the rights of corporations to spend money in non-candidate elections (i.e., ballot initiatives and referendums).

- 1990: Austin v. Michigan Chamber of Commerce: The Supreme Court upheld the right of the state of Michigan to prohibit corporations from using money from their corporate treasuries to support or oppose candidates in elections, noting: “corporate wealth can unfairly influence elections.”9

- 2002: Passage of the Bipartisan Campaign Reform Act of 2002 (McCain–Feingold), which banned corporate funding of issue advocacy ads that mentioned candidates close to an election.

- 2010: Citizens United v. FEC: The Supreme Court held that corporate funding of independent political broadcasts in candidate elections cannot be limited under the First Amendment, overruling Austin (1990).

The 2012 Presidential Election

The 2012 US presidential race was the most expensive in history. According to the Federal Election Commission, approximately $6 billion was spent on the election by candidates, parties, and outside groups. Of that, $933 million came directly from companies, unions, and individuals funneling money into Super PACs specifically enabled by Citizens United. The Center for Public Integrity found that nearly two-thirds (approximately $611 million) went to just ten political consulting firms, who spent 89 percent of the money on negative advertising spots attacking candidates.10Influence of the Wealthy: The One Percent of the One Percent

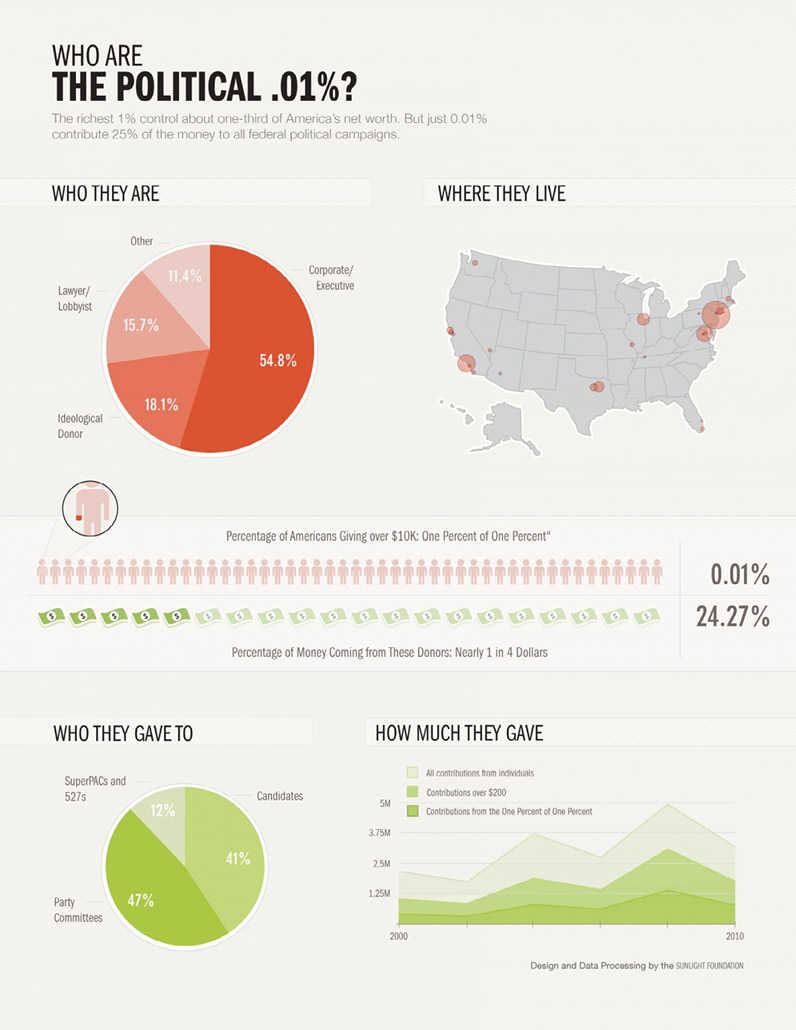

According to the Sunlight Foundation, there is a growing dependence on the One Percent of the One Percent—an elite group of the wealthiest Americans, including corporate executives, investors, lobbyists, and lawyers in metropolitan areas who give to multiple candidates, parties, and independent issue groups. Data suggests that, while these ideological donors make up less than 1 percent of the US population, they control about one-third of America’s net worth and contribute up to 25 percent of the money provided to all federal political campaigns.11

Case Study: Citizens United v. Federal Elections Commission

In early 2010, the United States Supreme Court shocked much of the nation when it ruled that corporations have the same rights of political free speech as individuals under the First Amendment to the US Constitution.

Citizens United v. Federal Elections Commission was a constitutional law case challenging the Bipartisan Campaign Reform Act (BCRA) of 2002, otherwise known as the McCain–Feingold campaign finance law. The BCRA barred corporations and unions from running broadcast, cable, or television ads for or against Presidential candidates for thirty days before primary elections, and within 60 days of general elections. In addition, the law required donor disclosure and disclaimers on all materials not authorized or endorsed by the candidate.

The Supreme Court

The United States Supreme Court plays a central and occasionally polarizing role in the American democratic system. Created by the Judiciary Act of 1789, the Supreme Court is the only court specifically prescribed by the Constitution. As the “highest court in the land,” it remains the functional and symbolic defender of American civil rights and liberties.

As the United States’ final court of appeal, the Supreme Court is the ultimate interpreter of law in the United States. With the authority to strike down any federal and state law it deems unconstitutional, the Court acts as a check on the power of the executive and legislative branches of government. In theory, the Supreme Court guarantees that changing majority views don’t subjugate vulnerable minorities or undermine fundamental American values such as freedom of speech.

Because it often appears to defend these values in direct opposition to popular opinion, the Supreme Court has been criticized as an antidemocratic institution that fails to take into account progressive social evolution. Indeed, justices are often accused of ideological activism, constitutional fundamentalism, and ignorance of the changing face of the American public. It can also be argued, however, that the Supreme Court’s decisions historically have reflected growing national sentiments about constitutional issues more consistently than it has rejected them.

Virtually every political and social hot-button issue—abortion, gay marriage, affirmative action, civil rights, immigration, and so on—appears before the Supreme Court at some point. Justices are appointed for life so that, ideally, they will not be swayed by outside political influences; unlike the president or Congress, they do not have to worry about re-election campaigns or approval ratings. The Supreme Court’s decisions have often had sweeping and profound consequences to society, and they almost always inflame passions on both sides of the political spectrum.

The Plaintiff

Citizens United, a conservative nonprofit corporation, wanted to run an on-demand cable documentary called Hillary: The Movie, which harshly criticized then-Senator Hillary Clinton during the Democratic presidential primary in 2008. The documentary featured interviews with conservative pundits and politicians who claimed that Clinton would be a presidential disaster.

The Federal Elections Committee (FEC) blocked the documentary from being broadcast, designating it as “electioneering communication” under the BCRA. Citizens United brought its case to the United States District Court for the District of Columbia, citing violation of the group’s First Amendment rights, but the lower court sided with the FEC. The case was appealed and appeared before the Supreme Court in early 2009.

Origins

In 2004, Michael Moore released a documentary, Fahrenheit 9/11, shortly before the GOP primary elections. The movie was a scathing indictment of George W. Bush, his administration’s War on Terror, and the far-reaching consequences of his first term as President. Citizens United filed a complaint with the FEC, stating that ads for the film were television broadcast communications designed to influence voters, and therefore violated federal election law. The FEC dismissed the complaint, saying it was clear that Fahrenheit 9/11, along with its television trailers and website, were purely commercial pursuits. In response, Citizens United decided to start producing its own “commercial” documentaries.

Arguments

Before the Supreme Court, Citizens United argued that the BCRA (the McCain–Feingold Act) only applied to commercial advertisements, not to video-on-demand, 90-minute documentaries such as Hillary: The Movie. The group’s lawyer, Ted Olson, did not even mention the First Amendment, nor did he call for the repeal of any part of federal election law.

Taking the opposite position was the deputy solicitor general, who argued that the Clinton documentary was the equivalent of an extended campaign advertisement, recalling the Supreme Court’s decisions in Austin v. Michigan Chamber of Commerce (1990), which held that state legislatures may prohibit corporations from using treasury funds on electoral speech, and McConnell v. Federal Election Commission (2003), which validated the BCRA’s spending limitations, stating that “express advocacy and its functional equivalent may be treated alike, and that BCRA’s definition of ‘electioneering communication’ is not facially overbroad.”12

First Opinion

After the case was argued, the Court decided that the BCRA did not apply to Hillary: The Movie, and therefore Citizens United could air it unhindered. Chief Justice John Roberts drafted an opinion, but it soon became clear that many of the justices didn’t think it went far enough. The conservative majority felt that the case was a perfect opportunity to broaden the discussion to address whether or not corporate speech should be regulated at all under the Constitution.

Roberts withdrew his opinion, and the Court called for the case to be reargued in September, almost a month before the official start of the fall term and two months before the 2010 midterm election. The justices directed the parties to file supplemental briefs addressing the question of whether the Court should overrule Austin v. Michigan and parts of McConnell v. FEC, which would amount to eliminating decades of restrictions on corporate electoral spending.

Second Opinion

The Citizens United case was reargued on September 9, 2009. By a five-to-four vote, the conservative majority held that the First Amendment to the United States Constitution prohibits the government from imposing any limits on political spending by corporations, associations, and unions. Justice Anthony Kennedy wrote the majority opinion, which he summarized from the bench in this way: “Political speech is indispensable to decision making in a democracy and this is no less true because the speech comes from a corporation rather than an individual.”13

Justice Kennedy was joined by Chief Justice John Roberts and Justices Antonin Scalia, Samuel Alito, and Clarence Thomas. To the conservative judges, the ruling was a vindication of the power of free speech; because of Citizens United, the First Amendment could now be applied universally and without prejudice.

Dissent

Justice John Paul Stevens wrote a highly critical 90-page dissent, arguing that Justice Kennedy’s opinion constituted “a rejection of the common sense of the American people, who have recognized a need to prevent corporations from undermining self-government since the founding.”14 Stevens believed that the limits Congress had for years imposed on corporate spending were necessary to curb political corruption by the wealthiest Americans, who would inevitably out-spend, out-lobby, and “out-speech” the vast majority of Americans. Stevens also argued that corporations are not “people” in the real sense—they do not have consciences, feelings, beliefs, or desires—and therefore are not true members of society, or “‘We the People,’ by whom and for whom [the] Constitution was established.”

Justice Stevens was joined in his dissent by Justices Ruth Bader Ginsburg, Stephen Breyer, and Sonia Sotomayor. These liberal justices recognized that the decision would open the floodgates for spending in electoral campaigns, making it “exceedingly difficult to maintain that independent expenditures by corporations ‘do not give rise to corruption or the appearance of corruption.’”15

Corporate “Personhood”

Widespread public criticism of the Citizens United decision has not diminished with time, particularly from liberal or progressive voters and pundits. Protesters, lawmakers, and organizations such as Move to Amend have called for a constitutional amendment to overturn the ruling. Across the country, a number of public demonstrations were held where participants waved signs reading, “Corporations Are Not People.” Despite the widespread outrage, the reality is that corporations have had many of the same rights as individuals for a very long time.

Corporate personhood refers to the legal concept that allows organizations of people, as individuals acting collectively, to be both protected by the Constitution and subject to the same laws as citizens. The word corporation derives from the Latin, corpus, meaning body, and is defined as “a body of people acting jointly, …recognized by law as acting as an individual.”16

The Romans first devised corporate personhood as a way for cities and churches to legally organize for the purposes of joint land ownership, taxation, and institutional perpetuity. Creating a “legal” or “artificial” person made it unnecessary to develop separate laws enabling large groups of people to do the same things as individuals: for instance, make contracts, own property, pay taxes, borrow money, enter into law suits, and be protected from persecution.

Since at least 1819, in Trustees of Dartmouth College v. Woodward, the Supreme Court has recognized corporations as having the same rights as “natural persons” for the purpose of contracts. Since then, the Supreme Court has given corporations increasingly more rights traditionally reserved for natural people: Fourteenth Amendment rights of equal protection (Pembina Consolidated Silver Mining Co. v. Pennsylvania, 1888), Fifth Amendment protections of due process (Noble v. Union River Logging, 1893), Fourth Amendment search and seizure protection (Hale v. Henkel, 1906), double-jeopardy immunity (Fong Foo v. United States, 1962), First Amendment protection (Grosjean v. American Press Company, 1936), Seventh Amendment rights to trial by jury (Ross v. Bernhard, 1970), the right to spend money in noncandidate elections (First National Bank of Boston v. Bellotti, 1978), and the right to spend in campaigns as a form of “speech” (Buckley v Valeo, 1976).17

Amending the Constitution to Overrule Citizens United

Move to Amend, a coalition of political interest organizations, lead the campaign for a Constitutional amendment that would overturn the Supreme Court’s decision in Citizens United. MoveToAmend.org clearly states:

We, the People of the United States of America, reject the US Supreme Court’s ruling in Citizens United and other related cases, and move to amend our Constitution to firmly establish that money is not speech, and that human beings, not corporations, are persons entitled to constitutional rights.18

Consequences

Specialists in campaign finance law predict that the Supreme Court’s ruling will shape the US electoral process for years to come. The matter is far from settled, however, as there is a growing movement of nonpartisan municipal, county, and state bodies calling for a constitutional amendment to overturn the decision. Citizens United’s legacy is far from over.

Topic for Debate: Overrule Citizens United

In this debate section, you will be asked to assume the role of a college student at a SUNY campus in New York State. The Congressional representative who has been elected from your university’s district has introduced a bill in Congress that would authorize a constitutional amendment to overturn Citizens United. The university newspaper has sponsored a public debate so that the it can determine what position to take—should the newspaper endorse (or not) the proposed amendment? You have been invited to be a part of one of the two debate teams that will address the issue at a public forum. You are expected to base your arguments to some extent on the statements and publications of legal and public policy experts.

Affirmative

The university newspaper should endorse a constitutional amendment to overturn Citizens United.

Possible Arguments

- Corporations are not people, and should not have the same rights as individuals.

- The Supreme Court erred with its decision in Citizens United, due to judicial activism.

- Electoral issues should be decided by elected officials and not by the Supreme Court.

- Corporate money inherently leads to political corruption and “secret” financing.

- Wealthy Americans by and large represent the corporate interests of America and should not drown out the voices of those with less power and money.

Negative

The university newspaper should oppose a constitutional amendment to overturn Citizens United.

Possible Arguments

- American democracy relies on freedom of speech, which should therefore be enjoyed by everyone, regardless of their legal status.

- Corporate money in elections increases political competition and awareness of issues.

- Americans can decide for themselves whether or not to elect a candidate; ads don’t make a difference either way.

- Corporations advocate for their employees, customers, and communities, and regulation will only constrain this ability.

- Corporations are fundamental to American economic progress and should be allowed to influence the political process to maintain their positive contributions to society.

Readings

11.1 Supreme Court Opinion and Pleadings

The Supreme Court’s majority opinion, the various dissenting and concurring opinions, and the parties’ briefs, may be accessed on the Internet at the following links:

The official arguments and decision can be found at “Citizens United v. Federal Election Commission.” The Oyez Project at IIT Chicago-Kent College of Law. Last updated August 25, 2014. http://www.oyez.org/cases/2000-2009/2008/2008_08_205.

The official briefs and amicus briefs can be found at “Citizens United v. Federal Election Commission.” SCOTUSblog. June 17, 2010. http://www.scotusblog.com/case-files/cases/citizens-united-v-federal-election-commission/

A video can be found at “The Story of Citizens United v. FEC (2011).” YouTube video, 8:50. Posted by “storyofstuffproject” on February 25, 2011. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=k5kHACjrdEY.

11.2 “Why Super PACs Are Good for Democracy: Super PACs Get Government out of the Business of Regulating Speech”

Smith, Bradley A. “Why Super PACs Are Good for Democracy: Super PACs Get Government out of the Business of Regulating Speech.” U.S. News and World Report. February 17, 2012. http://www.usnews.com/opinion/articles/2012/02/17/why-super-pacs-are-good-for-democracy.

11.3 “The New York Times’ Disingenuous Campaign against Citizens United”

Kaminer, Wendy. “The New York Times’ Disingenuous Campaign against Citizens United.” The Atlantic. February 24, 2012. http://www.theatlantic.com/politics/archive/2012/02/the-new-york-times-disingenuous-campaign-against-citizens-united/253560/.

The paper is promoting the misconception that the ruling allowed for unlimited campaign contributions from super-rich individuals. It didn’t.

Like Fox News, the New York Times has a First Amendment right to spread misinformation about important public issues, and it is exercising that right in its campaign against the Citizens United ruling. In news stories, as well as columns, it has repeatedly mischaracterized Citizens United, explicitly or implicitly blaming it for allowing unlimited “super PAC” contributions from megarich individuals. In fact, Citizens United enabled corporations and unions to use general treasury funds for independent political expenditures; it did not expand or address the longstanding, individual rights of the rich to support independent groups. And, as recent reports have made clear, individual donors, not corporations, are the primary funders of super PACs.

When I first focused on the inaccurate reference to Citizens United in a front-page story about Sheldon Adelson, I assumed it was a more or less honest if negligent mistake. (And I still don’t blame columnists for misconceptions about a complicated case that are gleaned from news stories and apparently shared by their editors.) But mistakes about Citizens United are beginning to look more like propaganda, because even after being alerted to its misstatements, the Times has continued to repeat them. First Amendment lawyer Floyd Abrams wrote to the editors pointing out mischaracterizations of Citizens United in two news stories, but instead of publishing corrections, the Times published Abrams’ letter on the editorial page, effectively framing a factual error as a difference of opinion…

As these examples suggest, …campaign-finance reforms dating back decades have produced an overcomplicated, overreaching web of laws and regulations that are easily abused, misunderstood, or intentionally obfuscated. The complexities of campaign finance law (and tax-code provisions governing independent groups) also create incentives to oversimplify the problems caused by the campaign-finance regime by naming Citizens United as the root of all evils. This helps advance what appears to be a simple solution—repeal Citizens United with a “free speech for people” constitutional amendment declaring that corporations aren’t people. Putting aside the dangers of this approach, it wouldn’t solve the problem of super PACs: The billionaires funding them may lack personal appeal but they are, after all, people, whose expenditures were not at issue in Citizens United. When the press promotes false understandings of Citizens United and the problems of campaign finance, it “paves the way” for false solutions.

It’s worth noting that the Times is not alone among proponents of reform in scapegoating Citizens United (although it seems to have taken the lead.) The New York Times, the Washington Post, and MSNBC regularly and routinely misstate the meaning and impact of the Supreme Court’s Citizens United decision on campaign finance rules,” Steve Brill recently observed, citing a post by Dan Abrams. Brill recommends confronting reporters and commentators with their frequent misstatements. Former ACLU Executive Director Ira Glasser has gamely tried engaging New York Times Public Editor Arthur Brisbane in an effort to stop misleading readers…Are you confused yet? What does the Times believe or want you to believe about Citizens United? Whatever.

11.4 “The Citizens United Catastrophe”

Dionne, E. J., Jr. “The Citizens United Catastrophe.” The Washington Post. February 5, 2012. http://www.washingtonpost.com/opinions/the-citizens-unitedcatastrophe/2012/02/05/gIQATOEfsQ_story.html

11.5 Experts Assess Impact of Citizens United: HLS Professor Suggests Constitutional Amendment Stating Corporations Are Not People

Greenfield, Jill. “Experts Assess Impact of Citizens United.” Harvard Gazette. February 3, 2012. http://news.harvard.edu/gazette/story/2012/02/experts-assess-impact-of-citizens-united/.

Few recent Supreme Court cases have received as much attention—and drawn as much ire—as Citizens United v. Federal Election Commission. In a 5–4 decision, the court ruled that the First Amendment prohibits government from placing limits on independent spending for political purposes by corporations and unions. To proponents of campaign finance reform, Citizens United had the detrimental effect of inundating an already-broken campaign finance system with corporate influence. At an event sponsored by the Harvard Law School (HLS) American Constitution Society on Tuesday, HLS Professor Lawrence Lessig, author of Republic Lost, and Jeff Clements, author of Corporations Are Not People, reviewed the impact that Citizens United has had on the political process.

Clements said that the court’s decision exacerbates two problems that the American political and electoral system had already been facing—the large amount of campaign spending and the growing influence of corporate power on the political process. Clements said that both problems need to be fixed in order to restore democracy but that, rather than addressing these problems, the Citizens United decision instead requires that the American people fundamentally reframe their notion of corporations.

“We need to look at what Citizens United really asks us to do, which is to accept a lot. The court asks us to pretend that corporations are not massive creations of state, federal, and foreign laws. It asks us to pretend that they’re just like people, that they have voices, and that we’re not allowed to make separate rules for them,” he said.

Although some legal observers regard the decision as simply a bad day on the court, Clements said that Citizens United actually represents the culmination of a steady creation of a corporate rights doctrine that is radical in terms of American jurisprudence. He provided a history of the idea of corporate personhood and corporate speech, which began only in the 1970s under Chief Justice William Rehnquist. Lessig added that the system that has resulted is one in which elected officials must spend 30 to 50 percent of their time fundraising, and thus make decisions based not on what is best for their constituents, but on what their super PACs and other major donors want to see.

“We have a corrupt government, yet one that is perfectly legal,” said Lessig. “We’ve allowed a government to evolve in which Congress isn’t dependent on people alone, but is instead increasingly dependent on its funders. As you bend to the green, that corrupts the government.”

As a result, he said, members of Congress develop a sixth sense as to what will raise money, which has led them to bend government away from what the people want government to do and toward what their funders want government to do. To fix the problem, we need to produce a system where the funders and the people are one and the same. The solution, Lessig said, is a multipronged approach that includes a constitutional amendment explicitly stating that corporations are not people, as well as a movement to publicly fund elections and provide Congress with the power to limit independent expenditures.

Synthesis Questions

- Do corporations have too much influence on American politics? Support your arguments with examples of excessive influence or lack of excessive influence.

- Why do so many people find it repugnant to treat corporations as “persons”? Is this disfavor justifiable?

Endnotes

1. “Remarks by the President in State of the Union Address,” Whitehouse.gov, January 27, 2010, accessed December 3, 2014, http://www.whitehouse.gov/the-press-office/remarks-president-state-union-address.

2. “Political Party Spending at Elections,” The Electoral Commission, accessed October 25, 2013, http://www.electoralcommission.org.uk/party-finance/party-finance-analysis/campaign-expenditure/uk-parliamentary-general-election-campaign-expenditure.

3. Anna M. Paperny, “Election Costs Have Skyrocketed in Past Decade, The Globe and Mail, August 23, 2012, http://m.theglobeandmail.com/news/politics/election-costs-have-skyrocketed-in-past-decade/article574996/?service=mobile.

4. Jefferson, Thomas. The Jeffersonian Cyclopedia. Funk and Wagnalls Company: New York and London. Jan. 1, 1900. http://archive.org/stream/thejeffersoncycl00jeffuoft/thejeffersoncycl00jeffuoft_djvu.txt

5. Nichols, John. “Feingold Fears ‘Lawless’ Court Ruling on Corporate Campaigning.” The Nation. Jan. 12, 2010. http://www.thenation.com/blog/feingold-fears-lawless-court-ruling-corporate-campaigning

6. Roosevelt, Theodore. “Fifth Annual Message.” The American Presidency Project. Dec. 5, 1905. http://www.presidency.ucsb.edu/ws/?pid=29546

7. “The FEC and the Federal Campaign Finance Law,” Federal Election Commission, last updated January 2013, http://www.fec.gov/pages/brochures/fecfeca.shtml.

8. Victor W. Geraci, “Campaign Finance Reform Historical Timeline,” Connecticut Network, accessed October 25, 2013, http://ct-n.com/civics/campaign_finance/Support%20Materials/CTN%20CFR%20Timeline.pdf.

9. Austin v. Michigan Chamber of Commerce, 494 U.S. 652 (1990). U.S. Supreme Court. March 27, 1990. http://caselaw.lp.findlaw.com/scripts/getcase.pl?court=US&vol=494&invol=652

10. Reity O’Brien, “Court Opened Door to $933 Million in New Election Spending,” The Center for Public Integrity, January 20, 2013, http://www.publicintegrity.org/2013/01/16/12027/court-opened-door-933-million-new-election-spending.

11. Lee Drutman, “The Political One Percent of the One Percent,” Sunlight Foundation, December 13, 2011, http://sunlightfoundation.com/blog/2011/12/13/the-political-one-percent-of-the-one-percent/.

12. Elena Kagan, “Citizens United, Appellant v. Federal Election Commission: Supplemental Brief for the Appellee,” The Supreme Court of the United States, no. 08-205, July 2009, http://www.justice.gov/osg/briefs/2009/3mer/2mer/2008-0205.mer.sup.pdf.

13. “Citizens United, Appellant v. Federal Election Commission, The Oyez Project at IIT Chicago-Kent College of Law, last updated August 25, 2014,http://www.oyez.org/cases/2000-2009/2008/2008_08_205.

14. Citizens United v. Federal Election Commission, 558 U.S. 310 (2010).

15. Mike Sacks, “Citizens United Foes John McCain, Sheldon Whitehouse Take Argument to Supreme Court,” Huffington Post, May 18, 2012, http://www.huffingtonpost.com/2012/05/18/citizens-united-john-mccain-sheldon-whitehouse-supreme-court-brief_n_1527622.html.

16. “Corporation.” Chambers Concise Dictionary. p. 267. Allied Chambers Publishers Ltd.: New Delhi. 2004.

17. “Timeline of Personhood Rights and Powers,” MovetoAmend.org, accessed October 25, 2013, https://movetoamend.org/sites/default/files/Timeline_36inch.pdf.

18. “Timeline of Personhood Rights and Powers.”