Week 7: Ways of Knowing Bzindamowin — Learning from Listening

StoryTelling

Anishnaabeg society was an oral society. One of the main ways of knowing was by storytelling. Each village had sort of an official storyteller called a debajehmujig. Stories, of which there were myriad, always contain at least one moral. The teaching was self-evident; the hearer expected to learn without intervention. These stories were simple enough to be understood by small children yet enjoyed by adults and elders alike.

The debajehmujig told the stories repetitiously at community gatherings held in the summer. Traditionally the people gathered at their main villages during the summer months. The people would gather in a large teaching lodge or around a large fire in the centre of the village, where the debajehmujig would spend warm summer evenings sharing stories with the communities. The young children especially enjoyed this activity.

The debajehmujig was not the only one to repeat these traditional stories. Elders and knowledge keepers, without encouragement, would also share them with the younger villagers. Parents would tell the stories to their children during the long winter nights in their hunting lodges. These tales so oft-repeated reinforced the learning by rote method without the need for explanation or testing.

Reading Assignment 1

Listening Assignment 1

How the dog and cat became our companions:

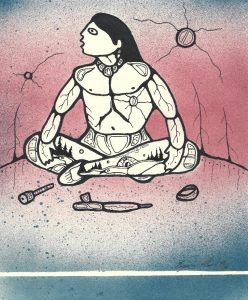

Nanabozho Stories

“Our Ahnishenahbek ancestors would spend these evenings in the warm, cozy lodges with the adults entertaining all with traditional stories. There were hundreds of stories, and in most, the central character was Nanabozho. He was a being whose father was a mahnedoo or spirit being, and his mother was human. He was a caricature of human nature, and often he would not do the things he should or would do the things he should not. His character was flawed with the more base human characteristics. He would often stumble along in an almost comical way exhibiting the inner weakness that all human beings struggle with. He means well, but his tendency to give in to this inner weakness often turns his adventures into misadventures and his successes into failures. Some of the stories of Nanabozho were very long, but most were short.”1

Name: Nanabozho

Tribal affiliation: Ojibway, Odawa, Potawatomi Algonquins, Menominees,

Alternate spellings: Wenabozho, Wenaboozhoo, Waynaboozhoo, Wenebojo, Nanaboozhoo, Nanabojo, Nanabushu, Nanabush, Nanapush, Nenabush, Nenabozho, Nanabosho, Manabush, Winabojo, Manabozho, Manibozho, Nanahboozho, Minabozho, Manabus, Manibush, Manabozh, Manabozo, Manabozho, Manabusch, Manabush, Manabus, Menabosho, Nanaboojoo, Nanaboozhoo, Nanaboso, Nanabosho, Nenabuc, Amenapush, Ne-Naw-bo-zhoo, Kwi-wi-sens Nenaw-bo-zhoo

Pronunciation: Varies by dialect: way-nuh-boo-zhoo, nuh-nuh-boo-zhoo, nain-boo-zhoo, muh-nah-boash, or mah-nah-boo-zhoo

Also known as: Michabo, Michabou, Michabous, Michaboo, Mishabo, Michabo, Misabos, Misabooz, Messou

Type: Culture hero, Transformer, trickster

Related figures in other tribes: Gluskabe (Wabanaki), Napi (Blackfoot), Whiskey Jack (Cree)

Nanabozho is the benevolent culture hero of the Anishinaabe tribes. His name is spelled so many different ways partially because the Anishinabe languages were originally unwritten (so English speakers just spelled the name however it sounded to them at the time), and partially because the Ojibway, Algonquin, Potawatomi, and Menominee languages are spoken across a huge geographical range in both Canada and the US, and the name sounds different in the different languages and dialects they speak. The differing first letters of his name, however, have a more interesting story: Nanabozho’s grandmother, who named him, used the particle “N-” to begin his name, which means “my.” Other speakers– who are not Nanabozho’s grandmother– would normally drop this endearment and use the more general prefixes W- or M-. So if you listen to a fluent Ojibwe speaker telling a Nanabozho story, he may refer to the culture hero as Wenabozho most of the time, but switch to calling him Nanabozho while narrating for his grandmother!

Stories about Nanabozho vary considerably from community to community. Nanabozho is usually said to be the son of either the West Wind or the Sun, and since his mother died when he was a baby, Nanabozho was raised by his grandmother Nokomis. In some tribal traditions Nanabozho is an only child, but in others he has a twin brother or is the eldest of four brothers. The most important of Nanabozho’s brother figures is Jiibayaabooz or Moqwaio, Nanabozho’s inseparable companion (often portrayed as a wolf) variously said to be his twin brother, younger brother, or adopted brother. Nanabozho is associated with rabbits and is sometimes referred to as the Great Hare (Misabooz), although he is rarely depicted as taking the physical form of a rabbit. Nanabozho is a trickster figure and can be a bit of a rascal, but unlike trickster figures in some tribes, he does not model immoral and seriously inappropriate behavior– Nanabozho is a virtuous hero and a dedicated friend and teacher of humanity. Though he may behave in mischievous, foolish, and humorous ways in the course of his teaching, Nanabozho never commits crimes or disrespects Native culture and is viewed with great respect and affection by Anishinabe people.[2]

Viewing Assignment 1

View the following Nanabozhoo stories:

The Legend of Turtle Island:

Nnabozho and the Geese:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=TKS9J9chMT0

More stories of Nanabozho:

Windigo Stories

Windigo stories were tales of cannibalistic monsters. They were designed to teach the immorality of selfishness and greed. People who indulged in these immoralities would be changed into windigos.

Viewing Assignment 2

Introduction to the Windigo:

Excerpt from David D Plain, 1300 Moons, Trafford Publishing: USA, 2007, pp205-208

Little Thunder came running to the village. He was now a boy very near the right of passage to manhood. He was all excited, shouting “Canoe’s are coming down river. It is The Fork!” Young Gull emerged from his lodge to watch his pride and joy bounding down the path that wound its way along the river bank toward the village. He was amazed at how quickly the dozen years had passed since Little Thunder’s naming ceremony.

The Fork beached his canoe, greeted Young Gull and Little Thunder watched as the two chiefs entered Young Gull’s lodge and closed the flap behind them. They are in there a long time thought Little Thunder. Then the two emerged and Young Gull went off to call a council for the following day. The Fork was taken to a newly erected lodge where he could rest. He was also provided with food and drink to replenish his strength. Later in the evening, around sunset, he called Little Thunder to his lodge.

“Come into my lodge” The Fork said. “I want to tell you a story”. Little Thunder obeyed the older chief from the Flint. His lodge was dimly lit by the small Fire in the center of it. The Fork took out his medicine bundle laying it in front of him. He took down his pipe, lit it, and then paused a long time as if collecting his thoughts. Little Thunder sat waiting cross-legged opposite the chief of the Flint River Band.

“There is a village half way between here and the Flint” The Fork began. “It is on the shores of a small lake called Nepissing and they had a young warrior named Black Cloud turn bad last winter. It was a hard winter and game was scarce. The people were down to eating bark and boiling their moccasins for soup. Black Cloud was so famished his thoughts turned from concern for the survival of the village to selfishly satisfying his own hunger.

Finally his selfishness led him to seek out a conjuror from the Society of the Dawn. They deal in magic and potions given to them by the Evil One. The conjuror gave Black Cloud a potion made of the roots of certain plants and told him to make a tea from it. He said it would enable him to find food but only for himself.

Black Cloud waited until early the next morning. When he arose he took the powder, made a tea and drank it all down. To his amazement he began to grow, taller and taller until he was twice as tall as any other warrior in his village. And such long strides he had. Deep snow was no barrier and he could out run even the swiftest of deer.”

Little Thunder sat mesmerized his eyes as wide as saucers. The Fork continued.

“Black Cloud set out over hills, through valleys and across rivers until he reached the top of the hill which overlooks my village. I was away hunting in a nearby valley so I missed the horrid spectacle that was about to take place.

Black Cloud’s appearance had changed. His skin had turned a gray, putrid color and gave off a rancid odor. It was the color and odor of death. This deathly skin was pulled tightly over his long, lanky skeleton and Black Cloud’s eyes had become sunken giving him the grotesque appearance of a monster. Black Cloud had become a windigo!

Down the hill it bounded toward the village shouting all the way. Its voice had become like the crack of overhead thunder. The windigo was an awesome and fearful sight, so much so that a few people immediately dropped dead. The rest fled.

When the windigo reached the village it did not avail itself of the winter’s supply of food stored nearby. Instead it found that the corpses which lay were they dropped had a strange appeal to its insatiable hunger. It began to eat the dead but they held no nourishment for it. Because of its selfishness the more of the lifeless flesh it ate the hungrier it became. When it finished it set off in search of more human flesh.

I returned the next day to find my village empty and the tell-tale signs that it had been visited by a windigo. Some of the dead that it had feasted on were my relatives. I was horrified and flew into a rage. I gathered my weapons and set out tracking the windigo. I came upon it resting in a valley near the Flint. It was in its habitual weakened state so when he saw me about to descend upon it, it begged for mercy. But I had none. I killed it on the spot and left its flesh as carrion for the vultures!”

Little Thunder left The Fork’s lodge astounded by the story. The sun had set and the village was dark and he was sure there was a windigo hiding behind every tree and every lodge he passed. He made it back to his parents lodge in record time with the story of the windigo from Nepissing buried deep in his heart. It was a tale designed to teach morals about generosity and greed, moderation and excesses and it would serve Little Thunder well for the rest of his life.

Seven Fires Prophesy

The Anishnaabeg were living on the Atlantic seaboard in the first millennium BCE. During that time, eight prophets visited them. The eight delivered seven prophecies to the people. Each relates to a specific era or block of time and is called a Fire.

Reading Assignment 2

https://caid.ca/SevFir013108.pdf Source www.7fires.org

Viewing Assignment 3

The Seven Fires Prophesy:

At the end of the 7th Fire, a choice of which path humanity will follow, one of materialism or spiritualism. The light-skinned race will make a choice. This choice will strike the 8th Fire, either a time of great peace or one of destruction. Complete the following two assignments for some thoughts on the 8th Fire.

Listening Assignment 2

Audio of 6th degree Mide’s vision of the future:

Viewing Assignment 4

The 8th Fire:

Migration Story

The Migration Story gives details of the Anishnaabeg following instructions of the Seven Fires Prophecy to migrate west. There were seven stopping places along the migration route. The following two assignments detail the seven stopping places.

Reading Assignment 3

Mishomis Book Migration Story:

https://www.wabanaki.com/wabanaki_new/documents/Mishomis%20Book%20Migration%20Story.pdf

Viewing Assignment 5

Ojibwe Migration:

Colonial Impact

Reading Assignment 4 personifies colonialism as a windigo. Nanabozhoo appears as a teacher to the Ojibwe of Minnesota, and the article traces colonialism’s effect on the people from its beginning to the present day.

Reading Assignment 4

https://tribalcollegejournal.org/nanaboozhoo-wiindigo-ojibwe-history-colonization-present/

Questions

- Besides morals, what other teachings do traditional indigenous stories carry?

- To what other things can the image of a windigo be applied?

- Which of the two possible 8th fires do you think will come to pass?

- Do you think the Mide’s vision is one of the 8th Fire?

- In the Mide’s vision of the future, do you think this is an absolute future or a propositional one?

[1] Plain David D Plain, Ways of Our Grandfathers, (Trafford Publishing, Victoria, B.C., 2007), 19

[2]Native American Legends: Nanabozho (Nanabush), available from http://www.native-languages.org/nanabozho.htm Internet: accessed 29 October 2021.

[3] Plain, David D. 1300 Moons, Trafford Publishing, USA: 2011, 205-208.