Week 2: Indigenous Worldview

Differences between Indigenous and Western worldviews have produced culture clashes since the very beginning of first contact. Culture clash results in misunderstandings of the things we say and do. The result is two people from different cultures talk past each other instead of speaking with each other. This lesson will look at how one Indigenous worldview developed and some examples of culture clash.

Creation Stories

In one Anishnaabeg creation story (there are more than one), Gchi-mnidoo (Great Mystery), the Creator creates the universe and all in it. He makes the sun, the moon and stars. He creates the earth, air, water. All that moves upon it, all that flies through it and all that swim in it. He made all the different kinds of trees and plants. He created the rocks and the mountains. He made all the four-legged creatures that walk on the earth. And all the birds that fly in the air and all fish that swim in the water. His final act of creation is human beings.

However, he created the humans weak, naked and vulnerable. He made them so they would not be able to survive on their own. So, he called a council of the spirits of everything he had created, and he asked them if they would be willing to help the humans survive. They went off to discuss the request among themselves and returned the next day. Yes, they answered. They had all agreed to help the humans to live.

We learned how the Western creation story helps their culture understand their place in the environment in lesson one. This story puts humanity at the bottom of the environmental hierarchy, which inverts the indigenous understanding of our place in the world. Our relationship with our environment is profoundly affected by our place on the scale. Because the other spirits have agreed to support and nurture us, the Anishnaabeg consider everything a gift from the Creator. We own nothing in this world except our bodies.

Mother Earth is the term we use for our environment because it provides the things we need for life. Tobacco is one of the four sacred plants. So, we practice laying down tobacco each time we take any of these things for our sustenance. When we cut saplings for our lodges, we give this thank-offering for the spirit of the trees for giving up their lives for us. When we have success at hunting, we do the same.

Other Ojibwe “creation stories” have to do with the creation of North America or “Turtle Island.” They take place after a great flood. Every indigenous people have creation stories, with each narrative having teachings within them.

Reading Assignment 1

Read the following paying attention to the Learning Activities and Expanding your knowledge sections.

Relationship to the Land

In the creation story, the spirits of the created things, including the land, agreed to nurture and support human beings. In the hierarchy of creation, it is above humanity and is our provider and sustainer. It does this by allowing humans to live upon it. We do not own it.

Indigenous people would often permit others to live among them, usually under a wampum treaty. Other times we made agreements to hunt in the same hunting grounds. The people understood that the land was our benefactor and the Ojibwe gave thanks with gifts of tobacco and prayers.

Reading Assignment 2

Read the following and view the clips.

How Indigenous Worldview Affects Societal Systems

Economic

We have learned that in the Anishnaabeg worldview, we own nothing, including the land’s produce. During our first contact with Europeans, they observed us annually taking the surplus of meat and fish products to our neighbours, the Ouendat or Huron nation. We would leave our goods with them taking their excess of corn, beans and squash home. They assumed that we were trading in the Western-style negotiating a trade agreement. We answered we called this activity daawed.

In reality, because everything is a gift, we were sharing excesses, not buying and selling. If one of the sharing partners experienced a bad year, the other partner would give them their surplus. It would be an insult to the Creator to hold back goods. On the other hand, Europeans did not exchange goods if they could not reach an agreement.

Justice

The hallmark of indigenous justice systems is to restore balance and harmony. It was the peace and order within the community and the broader community that concerned it. Indigenous justice included laws or rules that governed how communities and individuals related to each other. They also stipulated how people interacted with the world around them. Society did not codify these laws or regulations. Instead, they taught them through oral stories and teachings.

For example, if a squirmish between hunters from a Sioux village and an Ojibwe village and one or more got killed, the offending community had to provide restitution to restore harmony. They would do this by negotiating payment of goods for the life or lives of the slain. Both the victim’s village and their families had to settle, or the situation would escalate.

This form of justice appalled Western society. It was more concerned with punishment and rehabilitation of the individual, while Indigenous communities were more interested in restoring the balance between communities.

Whose rights are more important, the individual or the community? While the West answers the individual, Indigenous societies believe it is the community. Communities are so closely knit that embarrassment and shame at letting the community down almost always punished the individual. However, if one is incorrigible, the Council of Elders could decide to banish the individual.

Reading Assignment 3

Read the following article.

Political

Western society touts democracy as the preferred form of government. But Indigenous society was not democratic. Nor was it autocratic. Each nation governed itself by a group commonly called a council.

For example, the Ojibwe had a Council of Elders, and it appointed its members. If an individual past middle-aged exemplified wisdom, that person would be asked to sit on the council. It would be the wisdom of the community that governed it.

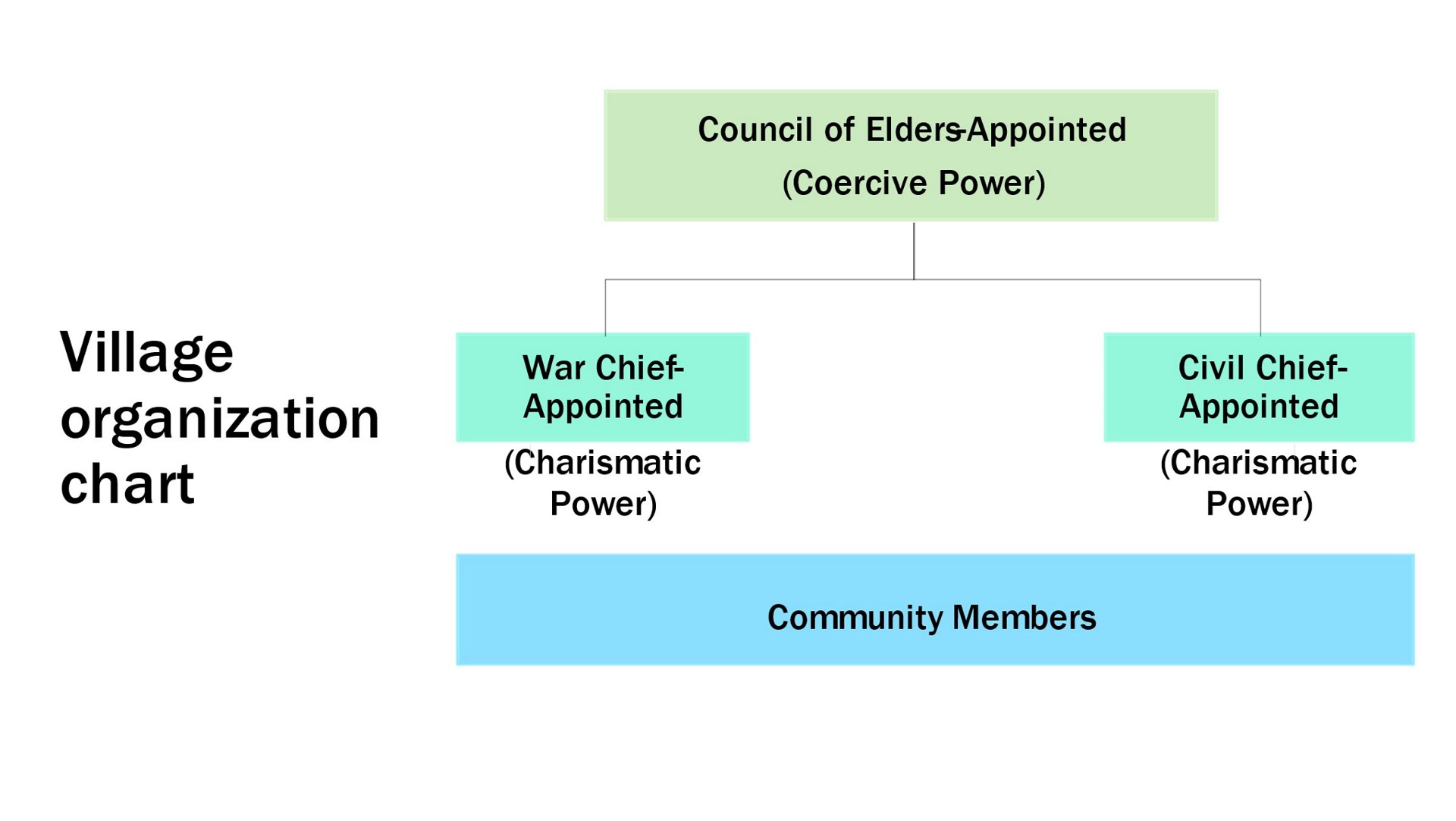

The polity was very autonomous and flatly organized. It had no central government. Each village had a Council of Elders and made decisions for its community. The Council of Elders had coercive power and appointed the chiefs who had charismatic power only. There were two types of Chiefs, War Chiefs and Civil Chiefs. The War Chiefs were responsible for raising was parties when required. The Civil Chiefs spoke for the Council of Elders, were great orators and negotiators.

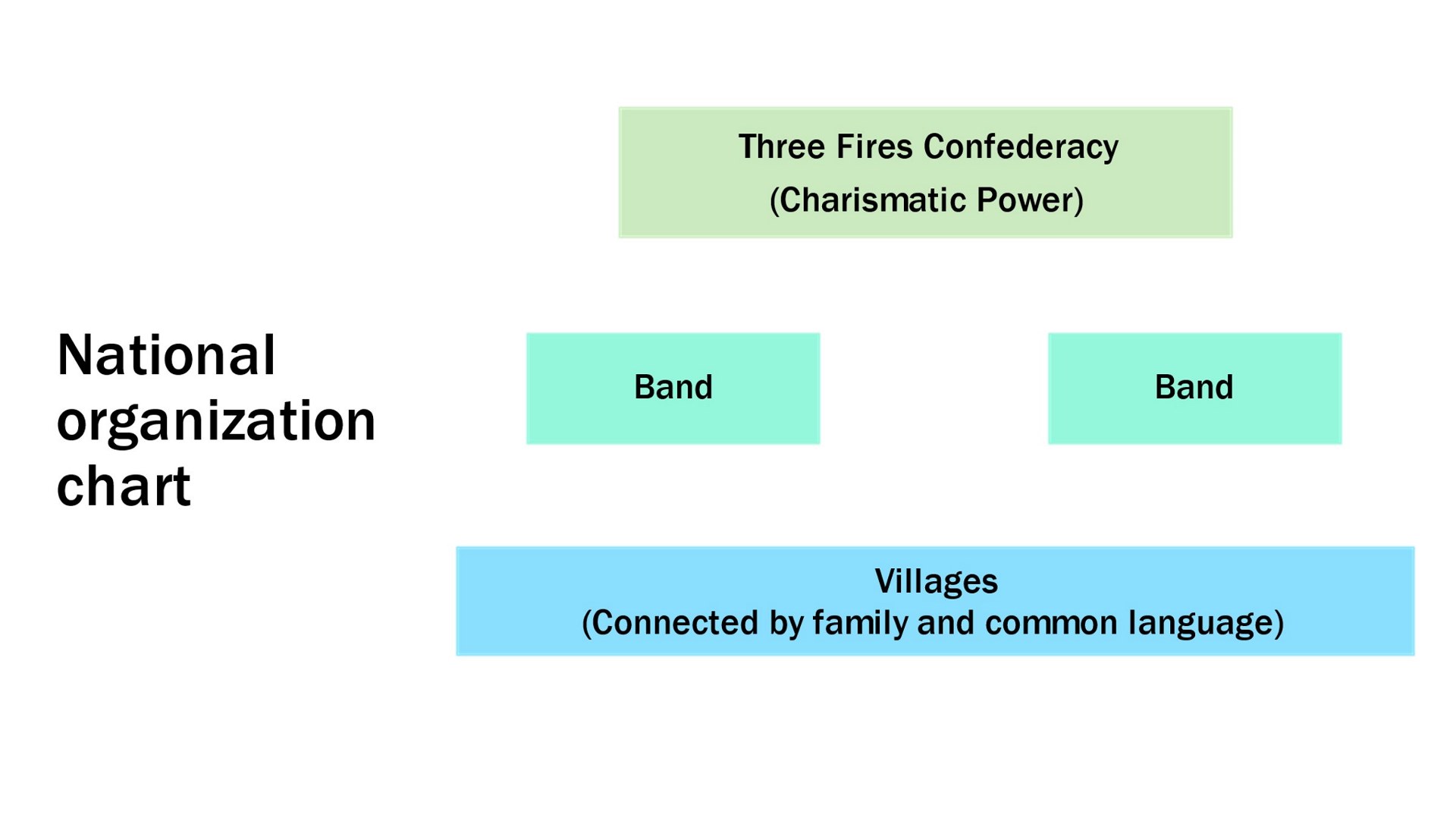

The Three Fires Confederacy member nations were the Ojibwe, Odawa and Potawatomie. It also had a Council of Elders made up of individuals from each member nation. It would convene whenever a problematic situation arose that affected each of the three member nations. An example would be whether to go to war against another nation or a confederacy of nations.

Viewing Assignment 1

For a detailed explanation of the Haudenosaunee political system view

Culture Clash Example

In 1818 the British Colonial Government approached the Saulteaux Ojibwe (Chippewa), expressing their desire to purchase all of their lands north of the Thames River in southwestern Ontario. Twenty-six chiefs met with John Askin, Superintendent of Indian Affairs at the Indian Council House, Fort Malden, Amherstburg, Ontario.

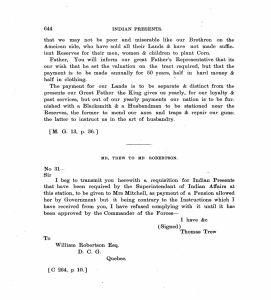

None of the chiefs understood English, and Mr. Askin did not speak Ojibwe. The translator was a Jesuit priest named Cadot. Askin informed the Chippewa the government wished to purchase all their lands north of the Thames River. The translator said in the Chippewa language they wanted to daawed all of their lands etc. They understood that the British were asking permission to live among them on the lands north of the Thames River. They agreed. The British understood the Chippewa had consented to a land title transfer to the Crown, thereby extinguishing Aboriginal title to the land. See the copy of the minutes below.

This misunderstanding resulted in a culture clash, where different meanings are attached to the words spoken because of each other’s culture. Compounding the misunderstanding was losing the sense in translation.

https://quod.lib.umich.edu/g/genpub/0534625.0016.001/653?rgn=full+text;view=image last viewed on July 24, 2021.

The final viewing assignment consists of three different videos. Each video is an interview with an elder talking about their people’s history, culture, and traditions. Each elder is from a distinct First Nation, and each First Nation is of a different linguistic stock.

The first video records elder Eddie-Benton Benai, an Ojibwe from Wisconsin. Ojibwe people are Algonkian speaking. The second video is of Andy Thundercloud, a Ho-Chunk which is Siouan. The last video tapes elder Randy Cornelius is Oneida, whose language is Iroquoian. What differences do you see between the three? What similarities?

Viewing Assignment 2

Video 1 https://pbswisconsin.org/watch/tribal-histories/wpt-documentaries-ojibwe-history/

Video 2 https://pbswisconsin.org/watch/tribal-histories/wpt-documentaries-ho-chunk-history/

Video 3 https://pbswisconsin.org/watch/tribal-histories/wpt-documentaries-oneida-history/