Week 11: Indigenous and Colonial Relationships, Effects of Colonialism Part 3

American Colonial Relations

The American Revolution

Excerpt from David D Plain, From Ouisconsin to Caughnawaga, Trafford Publishing 2013 pp 157-159.

The “Town Destroyer”

In 1778 the British send 200 of Colonel John Butler’s Rangers

into the Wyoming Valley to evict 6,000 illegal immigrants who

were squatting on “Indian lands”. They had with them 300

of their First Nation allies mostly members of the Three Fires

Confederacy. The Wyoming valley was situated in the middle of

the Seneca’s best hunting grounds and land never ceded by them.

Most of the forts the illegals had built were quickly abandoned

and the inhabitants fled. Fort Forty was the lone exception. When

the warriors feigned a withdrawal the colonials foolishly poured

out of their fort and into an ambush. This resulted in the killing

of 227 of them.

The Revolutionary government turned to propaganda releasing

a series of outlandish stories of the “massacre”. One such story read

that it was a “mere marauding, a cruel and murderous invasion

of a peaceful settlement . . . the inhabitants, men women and

children were indiscriminately butchered by the 1,100 men, 900 of

them being their Indian allies”. In truth there were only 500 men,

300 of them being their First Nation allies. And according to an

exhaustive study done by Egerton Ryerson only rebel soldiers were

killed and the misinformation put out by the Congress Party was

totally exaggerated and highly inflammatory.

Colonial propaganda was designed to inflame hatred among

the populace toward the British’s First Nation allies. However, it

had the effect of inflaming hatred toward all First Nation’s people

due to the decades of violence along the frontier over land. The

158 David D Plain

frontiersmen were convinced they had the right to push ever

westward while harboring in their hearts the axiom “the only good

Indian is a dead Indian”.

General Washington bought into his own government’s

propaganda releases. In 1779 he decided to act. The Six Nation

Iroquois League was divided on where their loyalties lay. Only

the Oneida and Onondaga backed the rebel cause and even their

loyalties were split. Washington charged General John Sullivan

with a war of extermination against the Iroquois. Sullivan headed

into Iroquois territory with an army of 6,500 men. His war of

extermination was a failure but he did destroy forty Seneca and

Cayuga towns along with burning all their crops. Although it is

true that atrocities were committed by both sides those committed

by the rebels were mostly forgotten. During this campaign the

Iroquois dead were scalped and in one instance one was skinned

from the waist down to make a pair of leggings!

The famished Iroquois fled to Niagara where they basically

sat out the rest of the war. With their crops destroyed the British

supplied them with the necessities putting a tremendous strain on

their war effort. This expedition earned George Washington the

infamous nickname of “Town Destroyer”. Now not only was any

hope gone of assistance from the Shawnee but also the Iroquois.

Meanwhile, in Illinois country George Rogers Clark was

determined to retake Fort Sackville at Vincennes. He had captured

it the year before only to lose it to Colonel Hamilton who had

marched immediately from Detroit. He left Kaskaskia on February

5th marching his 170 militiamen across flooded plains and waist

deep, freezing water. When he arrived at Vincennes he used the

old dodge of marching his men across a small patch of tableland

visible to the fort. He repeatedly marched them across this plateau

giving the enemy the impression that he had many more men

than he actually had. The history books claim that this had such

an alarming affect on the First Nations at the fort that they were

“scared off” by the ruse and the fort fell immediately.

It is true that the British were abandoned by their First Nation

allies. They were members of the Three Fires Confederacy. It is

From Ouisconsin to Caughnawaga 159

not true that they were “scared off”. Of the 170 militiamen with

Clark some were Frenchmen from New Orleans. The French,

like some of the First Nations, were also split in their allegiances.

Captain Alexander McKee wrote to Captain R.B. Lernoult

quite worried about news he had received regarding Three Fires

support. In the letter he wrote that the Ottawa and Chippewa

had sent a belt of peace to other surrounding nations saying they

had been deceived by the British and the Six Nations into taking

up the hatchet against the rebels. If they remained with the

hatchet in their hands they would be forced to use it against their

brothers the French. They reported seeing them coming with

Clark and his Virginians and therefore withdrew as they still had

great affection for the French. Old loyalties die hard. They were

determined now to lay down the hatchet and remain quiet thus

leaving the whites to fight among themselves. They were advising

their brothers the Shawnee to do the same and that the tribes of

the Wabash were also of like mind. This was not good news for

the British.

The withdrawal of support from the Three Fires Confederacy

and the sidelining of the Six Nations Iroquois that year left the

British with only support from the Miami, Shawnee and some of

the Delaware. There would be more atrocities to follow but still

it would be another three years before the British would see any

Three Fires’ support.

Gnadenhutten Massacre 1782

Ohio History Central

Excerpt from David D Plain, From Ouisconsin to Caughnawaga, Trafford Publishing 2013 pp159-162.

Massacre at Gnadenhutten

Hatred toward First Nations people by the rebels continued

to be the norm among the general populace. Most, especially

frontiersmen, failed to distinguish between their First Nation

160 David D Plain

allies, their First Nation enemies and the First Nation communities

that were neutral and wanting only to sit out the war in peace.

In the spring of 1782 the Moravian Delaware were living near

their town of Gnadenhutten on the Muskingum River. They had

been long converted to Christianity by the Moravian missionaries

and had taken up western societies’ ways. They were farmers. They

wore European dress and had their hair cropped in European

style. They lived in houses rather than lodges. They worshipped

in a Christian church on Sundays. Their community functioned

under the auspices of their Moravian mentors.

The Muskingum had become a dangerous war zone. They

realized the danger was particularly heightened for them being

“Indians”. They had determined to abandon their farms and move

the whole community further west to seek safe haven among the

Wyandotte of Sandusky as many of their Delaware brothers who

were not Christian had done already.

Before they could leave they were approached by Colonel

David Williamson and 160 of his Colonial Militia. They

claimed to be on a peaceful mission to provide protection and

to remove them to Fort Pitt where they could sit out the war in

peace. The leaders of the Gnadenhutten community encouraged

their farmers to come in from the fields around Salem and take

advantage of the colonel’s good offer. When they arrived all were

relieved of their guns and knives but told they would be returned

at Fort Pitt.

As soon as they were defenseless they were all arrested and

charged with being “murders, enemies and thieves” because

they had in their possession dishes, tea cups, silverware and

all the implements normally used by pioneers. Claims that the

missionaries had purchased the items for them went unheeded.

They were bound and imprisoned at Gnadenhutten where they

spend the night in Christian prayer. The next day the militia

massacred 29 men, 27 women and 34 children all bound and

defenceless. Even pleas in excellent English on bended knees failed

to save them. Two escaped by pretending to be dead and fled to

Detroit where the stories of the rebels’ atrocities were told.

From Ouisconsin to Caughnawaga 161

The Virginians decided to continue the massacre at

Gnadenhutten with a campaign of genocide. The plan was to

take the Wyandotte and their allies at Sandusky by surprise and

annihilate all of the inhabitants. They gathered a force of 478 men

at Mingo Bottoms on the west side of the Ohio River. General

Irvine, who had abhorred Williamson’s actions at Gnadenhutten,

deferred command of the expeditionary force to Colonel William

Crawford.

The force left Mingo Bottoms on May 25th avoiding the main

trail by making a series of forced marches through the wilderness.

On the third day they observed two First Nation scouts and

chased them off. These were the only warriors they saw on their 10

day march. Just before they crossed the Little Sandusky River they

came unwittingly close to the Delaware chief Wingenud’s camp.

Finally Crawford arrived at the Wyandotte’s main village

near the mouth of the Sandusky River. He assumed his covert

operation had been a success and they had arrived at their objective

undetected. But he was dead wrong. His Virginia Militia had

been closely shadowed by First Nation scouts and reports of their

progress had been forwarded to the chiefs.

War belts were sent out to neighboring Delaware, Shawnee

and other Wyandotte towns and their warriors had gathered at the

Half King Pomoacan’s town. Alexander McKee was also on his

way with 140 Shawnee warriors.

An urgent call for help had been sent to the British

commandant Major Arent S. De Peyster at Detroit. He responded

by sending Captain William Caldwell with 70 of his rangers. One

hundred and fifty Detroit Wyandotte joined Caldwell along with

44 “lake Indians”. Caldwell complained to De Peyster “The lake

Indians were very tardy but they did have 44 of them in action”.

These “lake Indians” were Chippewa warriors from

Aamjiwnaang at the foot of Lake Huron. The Aamjiwnaang

Chippewa were members of the Three Fires Confederacy and

were at Vincennes when they withdrew support from the British

in 1779. The fact that they only raised 44 warriors attests to the

162 David D Plain

lack of their war chiefs’ support. They were probably young men

incensed by the stories of Gnadenhutten and acting on their own.

Crawford was dumbfounded when he arrived at the Wyandotte

village and found it deserted. He and his officers held council and

decided to move up river hoping to still take the Wyandotte by

surprise. They didn’t get far when they were met by the warriors

from Pomoacan’s town. They were held in check until McKee and

Caldwell arrived. The battle lasted from June 4th to the 6th and

resulted in a complete First Nation’s victory. The rebel’s expedition

to annihilate the Wyandotte ended in disaster for the Virginians.

It cost them 250 dead or wounded. Caldwell’s Rangers suffered

two killed and two wounded while the First Nations had four

killed and eight wounded.

Colonel Williamson was able to lead the rebel survivors back

to safety but Colonel Crawford was captured along with some of

the perpetrators of the Gnadenhutten massacre. They were taken

to one of the Delaware towns where they were tried and sentenced

to death. Their punishment for Gnadenhutten atrocities was not

an easy one.

Viewing Assignment 1

View the film The Moravian Massacre: http://turtlegang.nyc/gnadenhutten-massacre/ last viewed February 6, 2022.

Indian War of 1790-95

Wikiwand

Excerpt from David D Plain, From Ouisconsin to Caughnawaga, Trafford Publishing 2013 pp 166-181.

The Indian War of 1790-95

Little Turtle’s War

United States’ Indian policy grew out of the idea that

because First Nations fought on the side of the British during

the Revolutionary War they lost the right of ownership to their

lands when Britain ceded all territory east of the Mississippi.

First Nations were told that the United States now owned their

territories and they could expel them if they wished to do so. This

right of land entitlement by reason of conquest stemmed from

their victory over the British and the hatred of “Indians” which

had been seething for decades. They needed First Nation’s lands

northwest of the Ohio River to sell to settlers in order to raise

much-needed revenue. But the impoverished new nation could not

back up their new policy. So they took a different tact.

In March of 1785 Henry Knox was appointed Secretary of War

and he began to institute a new policy. He proposed to Congress

that there were two solutions in dealing with the First Nations.

The first was to raise an army sufficient to extirpate them.

However, he reported to Washington and Congress that they

didn’t have the money to fund such a project. The estimated

population of the First Nations east of the Mississippi and south of

the Great Lakes was 76,000. The Miami War Chief Little Turtle’s

new “Confederation of Tribes” was quickly gaining numbers and

strength and they were determined to stop American advancement

From Ouisconsin to Caughnawaga 167

at the Ohio. To try to beat them into submission not only seemed

infeasible but immoral. He argued it was unethical for one people

to gain by doing harm to other people and this could only harm

America’s reputation internationally.

The second solution, which he favored, was to return to

the pre-revolutionary policy of purchasing First Nation Lands

through the cession treaty process. In order to sell this idea to

Washington and Congress he pointed out that the First Nations

tenaciously held on to their territories and normally would not

part with them for any reason. This was because being hunting

societies the game on their lands supported their population. But,

as proven in the past, time and again, when too many settlers

moved into their territories game became scarce. Because the

land was overrun by whites and ruined as a hunting territory

they would always consider selling their territory and move their

population further west.

In 1785 an Ordinance was passed by Congress dividing

the territory north and west of the Ohio River into states to be

governed as a territory. In 1787 this Ordinance was improved upon

by passing the Northwest Ordinance appointing Major General

Arthur St. Clair governor of the new territory. The new Ordinance

covered a huge tract of land encompassing the present-day states

of Ohio, Michigan, Indiana, Illinois and Wisconsin. Land would

now be purchased and hostilities would cease unless “Indian”

aggression were to provoke a “just war”. America was determined

to expand westward as its very existence depended upon it. Clearly

there would be “just wars”.

The first of these cession treaties was signed at Fort Harmar

in 1789. This small cession did little to change the minds of the

First Nations Confederacy. Hostilities continued provoking the

first of the “just wars”. In 1790 President Washington authorized

St. Clair to raise troops to punish Little Turtle’s Confederacy of

Miami, Shawnee, Ottawa, Potawatomi and Ojibwa nations. He

raised an army of 1,200 militia and 320 regulars and set out from

Fort Washington, Cincinnati, under the command of Brigadier

General Josiah Harmar.

168 David D Plain

Little Turtle retreated before Harmar’s lumbering army. He

led Harmar deep into enemy territory where he had set a trap in

the Maumee River valley near present-day Fort Wayne, Indiana.

Harmar’s army was strung out in one long column. The trap was

sprung and Little Turtle attacked Harmar’s flank killing 183 and

wounding 31. Panic set in. Harmar retreated in disarray. Little

Turtle pursued intent on wiping out the American army. However,

an eclipse of the moon the next night was interpreted as a bad

omen so the pursuit was called off.

General Harmar claimed a victory but had to face a board of

inquiry. The defeat was whitewashed but Harmar was replaced by

General St. Clair who was a hero of the Revolutionary War. Little

Turtle’s stunning success bolstered the ranks of the Confederacy.

In 1791 St. Clair raised another army of 1,400 militia and 600

regulars. He marched them out of Fort Washington and took up a

position on high ground overlooking the Wabash River.

Little Turtle and his war council decided to take the

Americans head on. Not their usual tactic it took St. Clair by

surprise. Confederacy warriors scattered the Kentucky Militia.

Other militiamen shooting wildly killed or wounded some of

their own men. Bayonet charges were mowed down by fire from

the surrounding woodlands. St. Clair tried to rally his troops but

could not. With General Richard Butler, his commanding officer,

wounded on the battlefield he ordered a retreat. It was no orderly

one. Most flung their rifles aside and fled in a panic.

The American army was completely destroyed. Suffering

nearly 1,000 casualties it would be the worst defeat ever suffered

by the United States at the hands of the First Nations. Washington

was livid. He angrily cursed St. Clair for being “worse than

a murderer” and the defeat on the Wabash became known as

St. Clair’s Shame. On the other hand First Nations’ hopes and

confidence soared.

From Ouisconsin to Caughnawaga 169

Congress at the Glaize

St. Clair’s Shame left the fledgling new nation in a precarious

position. The First Nations had just destroyed the only army

the United States had. President Washington put Major General

Anthony Wayne in charge of building a new one and Congress

appropriated one million dollars toward the project.

Wayne’s nickname was “Mad Anthony” which he earned

during the Revolution, but there was nothing “mad” about the

man. He was methodical and extremely determined. Wayne set

out to build the new army at Pittsburgh. It would be an army well-trained,

disciplined and large enough to take care of the “Indian

problem”. And he would be sure to take enough time to ensure a

successful campaign.

He began recruiting in June of 1792. His goal was an army of

5,120 officers, NCOs and privates whipped into the crack troops

needed to defeat a formidable enemy. By the end of 1792 he had

moved twenty-two miles south of Pittsburgh to Legionville where

he wintered. In the spring of 1793 he moved to Hobson’s Choice

on the Ohio River between Cincinnati and Mill Creek. Finally, in

October of 1793 he made his headquarters near Fort Hamilton.

Wayne received new recruits daily all the time relentlessly

drilling them into the army he knew he needed. But all did not

go well with the project. Desertion rates were extremely high.

The First Nation’s stunning successes on the Wabash and in

the Maumee Valley had instilled terror in the hearts of ordinary

pioneers and moving further toward “Indian Country” only

heightened their fear. Many new recruits would desert at the first

sign of trouble.

The problem had become so chronic that Wayne posted a

reward for the capture and return of any deserter. After a court-martial

the guilty would be severely punished usually by 100

lashes or sometimes even executed. An entry in the Orderly Book

170 David D Plain

Mss. dated August 9, 1792 reads, “Deserters have become very

prevalent among our troops, at this place, particularly upon the

least appearance, or rather apprehension of danger, that some

men (for they are unworthy of the name of soldiers), have lost

every sense of honor and duty as to desert their post as sentries, by

which treacherous, base and cowardly conduct, the lives and safety

of their brave companions and worthy citizens were committed to

savage fury.”

Meanwhile, warriors from other First Nations joined the

confederacy Little Turtle and Blue Jacket had forged. In October

1792 the Shawnee hosted a congress held at the Glaize, where

the Auglaize River flows into the Maumee. Delegates from the

nations whose territories were being defended attended. These

were Wyandotte from Sandusky, Delaware, Shawnee, Mingo,

Miami, Munsee, Cherokee and Nanticoke. Also attending were

other First Nations from further away but all offering support for

the war effort. Some of these were Fox and Sauk from the upper

Mississippi, Six Nations and Mohican from New York, Iroquois

from the St. Lawrence and Wyandotte from Detroit. There were

also many warriors from the Three Fires Confederacy. They

were Ottawa, Potawatomi and Chippewa from Detroit as well

as Chippewa from Aamjiwnaang and Saginaw. There were even

some Chippewa from Michilimackinac. This was the largest First

Nation congress every brought together by First Nations alone.

Even though the United States had suffered two humiliating

defeats at the hands of the First Nation Confederacy they still

had little respect. Henry Knox characterized them as Miami and

Wabash Indians together with “a banditti, formed of Shawanese

and outcast Cherokees”. However, because their military was

in shambles and they had a deficiency in revenue peaceful

negotiations were preferable to another war.

Washington at first sent delegates to the Glaize from their First

Nation allies with offers to negotiate. There were still some groups

of individual First Nations friendly with the Americans despite the

treatment received. The delegation of “U.S. Indians” arrived and

the celebrated Seneca orator Red Jacket spoke for the U.S.

From Ouisconsin to Caughnawaga 171

Red Jacket rose to speak to the nearly one thousand conferees.

He spoke on two strings of wampum bringing the American

message that even though they defeated the mighty British and

now all Indian territories belonged to them by right of conquest

they may be willing to compromise. They offered to consider

accepting the Muskingum River as the new boundary between

the United States and “Indian Country”. But the Confederacy

saw no need to compromise. After all they had defeated American

armies not once but twice in the last two years. They insisted

the boundary agreed to in the Treaty of Fort Stanwix in 1768 be

adhered to. That boundary was the Ohio and they would accept

no other.

The Shawnee chief Painted Pole reminded Red Jacket that

while his Seneca group was in Philadelphia cozying up to the

Americans the Confederacy was busy defending their lands. Now

he was at the Glaize doing the Americans dirty work. He accused

Red Jacket of trying to divide the Confederacy and demanded that

Red Jacket speak from his heart and not from his mouth. Painted

Pole then took the wampum strings that Red Jacket had spoken

on and threw them at the Seneca delegation’s feet. Red Jacket was

sent back to the Americans with the Confederacy’s answer, “there

would be no new boundary line”.

There was a tell-tale sign at that conference that Red Jacket’s

task would be difficult if not impossible. In normal negotiations

the civil chiefs would sit in the front with the War Chiefs and

warriors behind them. In this arrangement it would be the much

easier to deal with Civil Chiefs that would negotiate. But at the

Glaize the War Chiefs sat in front of the Civil Chiefs meaning

that Red Jacket would be dealing with the War Chiefs.

The British sat in the wings waiting for the new republic’s

experiment in democracy to fail and hoping at least for an

“Indian boundary state” to be formed. The Spanish at New

Orleans also sat by hoping for this new “Indian State” as it would

serve as a buffer state preventing American expansion into Illinois

country. The British even had observers at the Great Congress at

the Glaize in the person of Indian Agent Alexander McKee and

172 David D Plain

some of his men. Hendrick Aupaumut, a Mohican with Red

Jacket’s emissaries, accused McKee of unduly influencing the

conference’s outcome. But the Americans were not about to be

deterred so easily.

Peace Negotiations

The year following Red Jacket’s failed negotiations President

Washington appointed three Commissioners to try to negotiate

a peace with the First Nations Confederacy. Benjamin Lincoln,

Timothy Pickering and Beverly Randolph left Philadelphia

travelling north to Niagara. John Graves Simcoe, Lieutenant-

Governor of Upper Canada, afforded them British hospitalities

while they waited for word on a council with the First Nation

chiefs. They hoped to meet with the Confederacy at Sandusky

that spring.

The Americans thought the British would be useful as an

intermediary, but the British’s interests were really making sure

the Confederacy didn’t fall apart and long-term that an “Indian

barrier state” would be formed. The United States also had

ulterior motives. Although they would accept a peace as long as

it was on their terms they would be just as happy with failure

to use as an excuse for their “just war”. Simcoe had assessed the

situation correctly when he wrote in his correspondence “It

appears to me that there is little probability of effecting a Peace

and I am inclined to believe that the Commissioners do not

expect it; that General Wayne does not expect it; and that the

Mission of the Commissioners is in general contemplated by the

People of the United States as necessary to adjust the ceremonial

of the destruction and pre-determined extirpation of the Indian

From Ouisconsin to Caughnawaga 173

Americans”. While all this was going on Wayne advanced his army

to Fort Washington.

Meanwhile Washington asked the Mohawk chief Joseph

Brant to travel to the Miami River where the Confederacy was

in council. He was to try to persuade the Chiefs to meet the

Commissioners at Sandusky. He was partially successful in that

they sent a delegation of fifty to Niagara to speak to the American

Commissioners in front of Simcoe.

The delegation demanded the Commissioners inform them

of General Wayne’s movements and they also wanted to know

if they were empowered to fix a permanent boundary line. The

Commissioners must have answered satisfactorily because the

delegation agreed that the Chiefs would meet them in council at

Sandusky.

The Commissioners travelled with a British escort along

the north shoreline of Lake Erie stopping just south of Detroit.

Fort Detroit had yet to be handed over to the Americans and

Simcoe refused to let them enter the fort so they were put up at

the house of Mathew Elliott an Irishman who had been trading

with the Shawnee for many years. While they were there another

delegation arrived from the Miami. The Chiefs had felt that the

first delegation had not spoken forcefully enough regarding their

demands that the original boundary line of the Ohio River was

to be adhered to and that any white squatters be removed to south

of the Ohio. They also wanted to know why, if the United States

was interested in peace, Wayne’s army was advancing? No answer

was forthcoming. However, the Commissioners did inform this

delegation that they were only authorized to offer compensation

for lands and it was the United States’ position that those lands

were already treated away. Besides, the United States felt that

it would be impossible to remove any white settlers as they had

been established there for many years. The delegation returned to

the Miami with the Commissioners’ response which was totally

unacceptable to the Chiefs.

A council was held at the foot of the Maumee rapids where

Alexander McKee kept a storehouse. Both McKee and Elliott

174 David D Plain

were there as British Indian Agents. Joseph Brant suggested they

compromise by offering the Muskingum River as a new boundary

line. The Chiefs were in no mood to compromise having just

defeated the American Army not once but twice. Brant accused

McKee of unduly influencing the Chiefs’ position. The Delaware

chief Buckongahlas indicated that Brant was right. With the

Confederacy unwilling to compromise and the United States,

backed by Wayne’s army, standing firm things appeared to be at

an impasse. The Chiefs crafted a new proposal. A third delegation

carried it to the Commissioners on the Detroit.

The First Nations said money was of no value to them.

Besides, they could never consider selling lands that provided

sustenance to their families. Since there could be no peace as long

as white squatters were living on their lands they proposed the

following solution:

We know that these settlers are poor, or they would

never have ventured to live in a country that has been

in continual trouble ever since they crossed the Ohio.

Divide, therefore, this large sum which you have offered

us, among these people; give to each, also, a proportion

of what you say you would give to us annually, over

and above this very large sum of money, and we are

persuaded they would most readily accept of it, in lieu

of that lands you sold them. If you add, also, the great

sums you must expend in raising and paying armies

with a view to force us to yield you our country, you

will certainly have more than sufficient for the purposes

of repaying these settlers for all their labours and their

improvements. You have talked to us about concessions.

It appears strange that you expect any from us, who

have only been defending our just rights against your

invasions. We want peace. Restore to us our country

and we shall be enemies no longer.

From Ouisconsin to Caughnawaga 175

The delegation also reminded the Commissioners that their

only demand was “the peaceable possession of a small part of

our once great country”. They could retreat no further since the

country behind them could only provide enough food for its

inhabitants so they were forced to stay and leave their bones in the

small space to which they were now confined.

The Commissioners packed up their bags and left. There

would be no council at Sandusky. They returned to Philadelphia

and reported to the Secretary of War, “The Indians refuse to make

peace.” Wayne’s invasion would be “just and lawful.”

Meanwhile, at the Maumee Rapids a War Feast was given and

the War Song sung encouraging all the young warriors to come

in defense of their country. “The whole white race is a monster

who is always hungry and what he eats is land” declared Shawnee

warrior Chicksika. Their English father would assist them and

they pointed to Alexander McKee.

The Battle of Fallen Timbers

While the United States was busy trying to relieve the First

Nations of their lands peacefully and on their terms General

Wayne was busy preparing for their “just” war. He moved steadily

west establishing Forts Washington and Recovery along the way.

They would serve his supply lines during the upcoming battles.

In October 1793 he reached the southwest branch of the Great

Miami River where he camped for the winter. The Confederacy

made two successful raids on his supply lines that autumn then

returned to the Glaize for the winter.

Meanwhile, Britain had gone to war with France in Europe.

Sir Guy Carleton, Canada’s new Governor, was sure that the

176 David D Plain

United States would side with France and this would mean war in

North America. He met with a delegation from the Confederacy

in Quebec and reiterated his feelings on a coming war with the

Americans. He informed them that the boundary line “must be

drawn by the Warriors.” He then ordered Fort Miami to be re-established

on the Maumee River just north of the Glaize as well

as strengthening fortifications on a small island at its mouth.

Lieutenant-Governor Simcoe visited the Glaize in April 1794

and informed the council that Britain would soon be at war with

the United States and they would reassert jurisdiction over lands

south of the Great Lakes and tear up the Treaty of Fort Harmer.

Several years before the Americans talked some minor chiefs and

other warriors into signing that treaty turning all lands formerly

held by the British over to the United States of America for a

paltry $ 9,000 and no mention of an “Indian” border. Meanwhile,

Indian Agents McKee and Elliott encouraged their Shawnee

relatives with the likelihood of British military support. All of this

was very encouraging indeed.

General Wayne had his army of well-trained and disciplined

men. They numbered 3,500 including 1,500 Kentucky

Militiamen. This army was not the lax group of regulars and

volunteers the Confederacy had defeated at the Wabash and

Maumee Valley. Neither was the Confederacy the same fighting

force of three years earlier. Many warriors had left to return to

their homelands in order to provide for their families.

The American Army left their winter quarters and moved

toward the Glaize. Little Turtle saw the handwriting on the wall.

He advised the council “do not engage ‘the General that never

sleeps’ but instead sue for peace”, but the young men would have

none of it. When he could not convince them he abdicated his

leadership to the Shawnee War Chief Blue Jacket and retired.

Blue Jacket moved to cut Wayne’s supply lines. He had a

force of 1,200 warriors when he neared Fort Recovery which was

poorly defended. Half of his warriors were from the Three Fires

Confederacy and they wanted to attack and destroy the fort for

psychological reasons in order to give another defeat for Wayne

From Ouisconsin to Caughnawaga 177

to think about. But Blue Jacket was against this plan. The day

was wasted taking pot shots at the fort and they never cut off

Wayne’s supply line. Blue Jacket’s warriors returned to the Glaize

deeply divided.

In the first week of August an American deserter arrived at the

Glaize and informed Blue Jacket of Wayne’s near arrival. He had

moved more quickly than anticipated and had caught them off

guard. Many the Confederacy’s 1,500 warriors were off hunting

to supplement their food supply. Others were at Fort Miami

picking up supplies of food and ammunition. Blue Jacket ordered

the villages at the Glaize to evacuate. Approximately 500 warriors

gathered up-river to make a defense at a place known as Fallen

Timbers. It was an area where a recent tornado had knocked down

a great number of trees.

Out-numbered six to one the warriors fought bravely. They

established a line of defence and when they were overcome by

the disciplined advance of American bayonets they retreated only

to establish a new line. This happened over and over until they

reached the closed gates of Fort Miami where they received the

shock of their lives!

The fort was commanded by Major William Campbell and he

only had a small garrison under his charge. He was duty bound

to protect the fort if it was attacked but not to assist the King’s

allies. If he opened the gates to the pleading warriors he risked not

only his own life but the lives of the soldiers under him. Not only

that but there would be a good chance of plunging England into a

war with the United States, a war they could not afford being fully

extended in Europe. He made his decision quickly. He peered over

the stockade at the frantic warriors and said “I cannot let you in!

You are painted too much my children!” They had no choice but

to flee down the Maumee in full retreat.

It was not the defeat at Fallen Timbers that broke the

confederacy. They could always regroup to fight another day.

It was instead the utter betrayal of their father the British they

did not know how to get over. It also established the United

States as a bona fide nation because it defeated Britain’s most

178 David D Plain

important ally along the frontier. One chronicler wrote that

it was the most important battle ever won by the United States

because it was the war with the First Nations’ Confederacy that

would make or break the fledging nation. It also showed just how

trustworthy the British could be as an ally. Years later Blue Jacket

would complain “It was then that we saw that the British dealt

treacherously with us”…

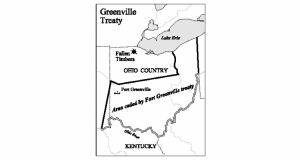

A Peace Treaty with Washington

From Ouisconsin to Caughnawaga 179

…the First Nations Confederacy under Blue

Jacket being defeated by General Anthony Wayne at Fallen

Timbers in 1794. The following year chiefs of the various First

Nations began arriving at Greenville, Ohio to negotiate a peace

treaty with the United States. That summer over 1,000 First

Nations people gathered around Fort Greenville. These included

chiefs from the Wyandotte, Delaware, Shawnee, Ottawa,

Chippewa, Potawatomi, Miami and Kickapoo.

This treaty was primarily a peace treaty between George

Washington, President of the United States, and chiefs representing

the above mentioned First Nations. My great-great grandfather

signed as one of the seven War Chiefs of the Chippewa. But not

all former combatants were represented. Among those missing

and vehemently against the peace were Shawnee chiefs Tecumseh

and Kekewepellethe. Rather than deal the Americans Tecumseh

with his followers migrated first to Deer Creek, then to the upper

Miami valley and then to eastern Indiana.

Land cessions were also included as part of the terms for

peace. Article 3 dealt with a new boundary line ‘between the

lands of the United States and the lands of the said Indian tribes’.

This effectively ceded all of eastern and southern present day

Ohio and set the stage for future land grabs. Included in the

United States’ ‘relinquishment’ of all ‘Indian lands northward of

the River Ohio, eastward of the Mississippi, and westward and

southward of the Great Lakes’ were cessations of sixteen other

tracks of land, several miles square, located either were U.S. forts

were already established or where they wished to build towns.

However, the term “lands of the said Indian tribes” had vastly

different meanings to the two sides.

The First Nations wanted their own sovereign country but the

United States dispelled any thought along these lines with Article

- It defined relinquishment as meaning “The Indian tribes that

have a right to those lands, are to enjoy them quietly . . . but when

those tribes . . . shall be disposed to sell their lands . . . they are

to be sold only to the United States”. In other words we had no

180 David D Plain

sovereign country but only the right to use lands already belonging

to the United States of America!

The Chippewa and Ottawa also ceded from their territories

a strip of land along the Detroit River from the River Raisin to

Lake St. Clair. It was six miles deep and included Fort Detroit.

The Chippewa also ceded a strip of land on the north shore of the

Straits of Mackinaw including the two islands of Mackinaw and

De Bois Blanc. The stage was now set for further U.S. expansion.

As a footnote the metaphorical language changed at the

conclusion of the peace agreement. First Nations had always

used familial terms when referring to First Nations and

European relationships. First the French and then the British

were always referred to as father. The Americans, since their

beginning, were referred to as brother. This continued through

the negotiations at Greenville until its conclusion at which time

the reference to Americans in the person of Washington changed

from bother to father.

Unfortunately because of a clash of cultures this patriarchal

term held different meanings to each side. To the First Nations

a father was both a friend and a provider. The Wyandotte chief

Tarhe spoke for all the assembly because the Wyandotte were

considered an uncle to both the Delaware and Shawnee and he

was the keeper of the council fire at Brownstown. He told his

‘brother Indians’ that they now acknowledge ‘the fifteen United

States of America to now be our father and . . . you must call

them brothers no more’. As children they were to be ‘obedient

to our father; ever listen to him when he speaks to you, and

follow his advice’. The Potawatomi chief New Corn spoke after

Tarhe and addressed the Americans as both father and friend.

Other chiefs spoke commending themselves to their father’s

protection and asked him for aid. The Chippewa chief Massas

admonished the assembly to ‘rejoice in acquiring a new, and so

good, a father’.

Tarhe eloquently defined a father for the American emissaries:

‘Take care of your little ones and do not suffer them to be imposed

upon. Don’t show favor to one to the injury of any. An impartial

From Ouisconsin to Caughnawaga 181

father equally regards all his children, as well as those who are

ordinary as those who may be more handsome; therefore, should

any of your children come to you crying and in distress, have pity

on them, and relieve their wants.’

Of course American arrogance stopped up their ears and they

could not hear Tarhe’s sage advice. Until this present day they

continue to live out their understanding of the term father as a

stern patriarch and one either to be obeyed or disciplined.

Viewing Assignment 2

View the film The Battle of the Wabash, last viewed February 6, 2022.

Tecumseh’s Vision 1808-13

Map Design: Monica Virtue used with permission

Excerpt from David D Plain, From Ouisconsin to Caughnawaga, Trafford Publishing 2013 pp 192-217, 240-250.

The War of 1812

Disaster at Prophetstown

Tecumseh arrived back at Prophetstown in late January 1812

but there was no warm welcome awaiting him. To his bitter

amazement the Shawnee town at the junction of the Tippecanoe

and Wabash Rivers lay in ruins. When told the details of the

disaster he was furious. He had left specific orders with his brother

not to engage the Big Knives but to appease them at all cost. He

had told Tenskwatawa, the Prophet that the time would come for

war, but not now. It was too early. It is reported that he was so

enraged that he grabbed his brother by the hair, shook him and

threatened to kill him.

The summer of 1811 was one of fear and apprehension all

along the frontier. The summer of unrest was caused by a few

young warriors loyal to Prophetstown but nevertheless hotheads

acting on their own. They had been raiding settler’s farms, stealing

their horses and a few had been killed.

William Henry Harrison, the governor of Indiana, met with

Tecumseh at Vincennes in July. Tecumseh tried to convince him

that the confederacy he was building was not for war but for

peace. He was not successful. They had met in council before

and although they had respect for each other they disagreed

strenuously. The year before their council almost ended violently.

From Ouisconsin to Caughnawaga 193

Winamek, a Potawatomi chief loyal to the Big Knives

suggested the warriors at Vincennes raise a large war party

and attack Prophetstown but Black Hoof convinced him

otherwise. Black Hoof and The Wolf two Shawnee chiefs loyal

to the Americans attended several councils with settlers in Ohio

convincing them that they and their three hundred warriors were

peaceful. Black Hoof took this opportunity to set all the blame for

all the troubles at the foot of Tecumseh and Tenskwatawa.

Meanwhile, in June some of Tecumseh’s entourage were

busy recruiting followers from the Wyandotte of Sandusky. They

encountered some resistance so they handled it by preying on the

Wyandotte’s fear of witchcraft. They accused their opposition

of it and three were burned alive as sorcerers including the old

village chief Leather Lips. American officials called for conferences

with their First Nation allies at Fort Wayne and Brownstown on

the Detroit River. They came from eastern Michigan, Ohio and

Indiana and all denounced the Shawnee brothers. The Shawnee

delegation to Brownstown was led by George Bluejacket and

Tachnedorus or Captain Logan the Mingo chief. Although they

affirmed their loyalty to the Big Knives they took the opportunity

to visit British Agents across the river at Amherstburg.

Harrison was convinced that all the turmoil on the frontier

emanated from Prophetstown. There was more trouble perpetrated

by the young hot head warriors. Three of these warriors believed

to be Potawatomi had stolen horses on the White and Wabash

Rivers terrorizing the settlers there. While Tecumseh was on

his three thousand mile sojourn building the confederacy

Harrison began to assemble a large army at Vincennes. He was

determined to disperse the First Nations who had congregated at

Prophetstown.

Harrison made his plans public telling Black Hoof to keep

his Shawnee followers in Ohio so they would not be connected to

the coming conflict. He also gave the same advice to the Miami

and Eel River Wea but his words did not sit well with some of the

Miami. Prophetstown was situated across the boundary in Miami

territory and they did not appreciate having their sovereignty

194 David D Plain

impinged upon. Word of the military buildup quickly traveled up

the Wabash to Prophetstown.

Tenskwatawa hurriedly call a council to decide what to

- The decision was made to send a Kickapoo delegation to

Vincennes. Probably led by Pamawatam the war chief of the

Illinois River Kickapoo the delegation was not successful. They

had tried to negotiate that a settlement of the troubles with the

settlers be sorted out in the spring.

The news they returned with was not good. Harrison had

assemble an army of one thousand soldiers and they were about

to march up the Wabash. The only thing that would deter them

was the return of stolen horses and for those who had committed

murders along the frontier to be handed over for punishment.

Harrison also demanded the dispersal of Prophetstown.

The Prophet had to decide whether to comply or fight.

They were not in good shape for a major battle. They needed

the little lead and powder they had to get them through the

upcoming winter. They were outnumbered. The congregation

at Prophetstown consisted of mostly Kickapoo and Winnebago

warriors that had camped there to hear Tenskwatawa preach along

with a sprinkling of Potawatomi, Ottawa, Ojibwa, Piankeshaw,

Wyandotte and Iroquois. There were also a small number of

Shawnee followers that lived there permanently. In total they could

only muster four to five hundred warriors. Tecumseh was right.

The time for a fight with the Big Knives had not yet arrived.

Harrison started the long, lumbering 180 mile journey up

the Wabash on the 29th of October. One third of the army he

commanded were regulars from the 4th Regiment of the U.S.

Infantry. The rest was made up of 400 Indiana Militia, 120

mounted Kentucky volunteers and 80 mounted Indiana riflemen.

Harrison had hoped that his show of American military might

would force Prophetstown to capitulate but he underestimated

First Nations tenacity. The Prophet decided to disregard

Tecumseh’s orders and stand and fight.

Prophetstown scouts monitored Harrison’s progress up the

eastern side of the Wabash while the warriors prepared spiritually

From Ouisconsin to Caughnawaga 195

for the upcoming battle. Tenskwatawa pronounce the Master of

Life was with them and the spirits would assist in the battle by

making them invisible. He prophesied that he had the power to

turn the American’s powder to sand and their bullets to mud.

When Harrison’s army arrived the warriors had worked

themselves into a frenzy. The Americans made camp about a mile

north of Prophetstown on a patch of high ground at Burnett’s

Creek. They sent a delegation to give The Prophet one last chance

to sue for peace but the three chiefs they met with refused the

offer. Harrison planned to attack the next day.

The Prophet and his council of war chiefs determined that

being outnumbered 2 to 1 and low on ammunition the only real

chance for success was to take the fight to Harrison that night.

Before dawn about 4 a.m. on the 7th of November 1811 the

warriors surrounded the American encampment. They could see

the silhouettes of the sentries outlined by their campfires. Harrison

and his officers were just being aroused for morning muster. The

surprise attack began.

The Winnebago led by Waweapakoosa would attack from

one side while Mengoatowa and his Kickapoo would strike from

the other. The warriors crept stealthily into position and just as

they were about to commence the assault an American sentry saw

movement in the underbrush that surrounded the encampment.

He raised his rifle and fired and the battle was on!

Blood curdling shrieks and war whoops filled the air

accompanied by volleys of gunfire from the darkness all around.

The warriors rushed forward and the American line buckled.

Others scrambled to form battle lines. The volleys of musketry

from the warriors were intense and some of the new recruits as

well as the riflemen protecting the far left flank broke for the

center. However, the main line of regulars held and the warriors

were unable to break through. The right flank now came under

a tremendous assault of gunfire from a grove nearby. Officer

after officer, soldier after soldier was felled. The line was about to

collapse when a company of mounted riflemen reinforced it.

196 David D Plain

The warrior’s surprise attack was now in trouble. The

American army was badly mauled but managed to hold.

Ammunition was running low and daylight was breaking. The

war party that had been so successful from the grove were now

uprooted by a company of riflemen and were in retreat. Harrison

turned from defense to offense routing the warriors who were

out of ammunition. They began a full retreat back to an empty

Prophetstown. When they arrived there with ammunition spent

they decided to disperse.

Harrison spent the rest of the 7th and some of the 8th of

November waiting for the warriors to commence a second assault.

When they didn’t he marched to Prophetstown only to find the

town’s inhabitants consisted of one wounded man and one old

woman who had been left behind. They were taken prisoner

but treated well. Harrison burned Prophetstown to the ground

including the granary. It was going to be a long, hard winter.

Harrison and his army limped back to Vincennes where

he would claim a great victory. But his badly mauled forces told

another story. American casualties amounted to 188 including

68 killed. First Nation estimates range from 25 to 40 killed. The

warriors had given a good account of themselves having assailed a

superior force on its chosen ground and inflicting higher casualties

on them.

War Clouds on the Horizon

When the Prophetstown warriors retreated from the battlefield

they carried some of their fallen with them. They quickly buried

them at their town and withdrew to see what Harrison would do

next.

From Ouisconsin to Caughnawaga 197

Although the Americans held their ground during the surprise

attack they were bruised and stunned. Harrison ordered them

to stand at the ready expecting the warriors to mount another

frontal assault. He waited all through November 7th and part way

through the 8th. That attack never came. Little did he know the

warriors had withdrawn due to lack of ammunition.

When the warriors failed to materialize he marched on

Prophetstown burning it to the ground destroying everything

that was there. The warriors watched from afar. They could see

the large billows of black smoke rising from the valley. The next

day their scouts informed them the Big Knives had left so they

returned to see what the enemy had done. They were horrified at

the sight that greeted them. Debased American soldiers had dug

up the fresh graves of their brave fallen warriors. The bodies were

strewn about and left to rot in the sun. They were livid. They reinterned

their dead and left for their hunting grounds short of

enough ammunition to get them through the winter.

Tecumseh’s confederacy had been dealt a serious setback.

Warriors from the several nations that had been at Prophetstown

left viewing the Prophet with disdain. They declared him to be a

false prophet because of the outcome of the battle. Tenskwatawa

claimed the spirits deserted them because his menstruating

wife had defiled the holy ground that he was drumming and

chanting on during the battle. Often a reason such as this would

be accepted for a failed prophecy. But not this time. The nations

from the western Great Lakes that supported Tecumseh and his

vision now rejected the Prophet which left them disenchanted

with Tecumseh’s vision as well. He had a lot of work ahead of him

rebuilding the confederacy.

Harrison was basking in the glory of self-proclaimed total

victory. He confidently claimed the Indians had been dispersed in

total humiliation and this would put an end to their depredations

upon white settlers up and down the frontier. The American

press lionized him and President Madison endorsed the message

in an address to congress on the 18th of December. The “Indian

problem” had been dealt with or so they thought.

198 David D Plain

That congress was bristling with war hawks enraged at Great

Britain mostly for impressing American merchant sailors at sea

into British service in their war with France. They thought that a

declaration of war on Great Britain and an attack on its colony of

Upper Canada would give them an easy victory and the whole of

the continent as a prize. Upper Canada was weakly defended and

Great Britain’s military might was stretched thin as all its resources

were being used in Europe.

In 1808 Congress tripled the number of authorized enlisted

men from 3,068 to 9,311. In 1811 Secretary of War, William

Eustis, asked for 10,000 more regulars. Virginia Democratic

Senator William Branch Giles proposed 25,000 new men.

Democrats for the most part held anti-war sentiments. It was

thought he upped the ante to embarrass the administration

because it was generally thought that 25,000 could not be raised.

However, Federalists William Henry Clay from Kentucky and

Peter B. Porter of New York pushed through a bill enacting

Giles’ augmentation into law on the 11th of January 1812. By

late spring authorized military forces had been further pushed to

overwhelming numbers: 35,925 regulars, 50,000 volunteers and

100,000 militiamen.

When Tecumseh had visited Amherstburg in 1810 he made

the British authorities there aware just how close the First Nations

were to rebellion. Upon realizing this they adjusted their Indian

Policy. Because of their weakened position they did not want to be

drawn into a war with the Americans. So they informed their First

Nation allies that the new policy stated that they would receive

no help from the British if they attacked the United States. If they

were attacked by the U.S. they should withdraw and not retaliate.

Indian Agents were ordered to maintain friendly relations with

First Nations and supply them with necessities but if hostilities

arose then they were to do all in their power to dissuade them

from war. This policy was continued by the new administrators

of Upper Canada. Sir James Craig was replaced as governor-general

by Sir George Prevost and Francis Gore with Isaac Brock

as lieutenant-governor.

From Ouisconsin to Caughnawaga 199

However, all the admonition to encourage peace by the British

and Harrison’s claim that peace on the frontier had already been

achieved by his victory at Tippecanoe was for nought. The British

lacked the necessary influence with the war chiefs and Harrison’s

proclamation was a myth. The Kickapoo and Winnebago suffered

through a particularly hard winter. The snow had been unusually

deep and game was scarce. The Shawnee suffered even more due

to the destruction of their granary. They were forced to survive by

the good charity of their Wyandotte brothers at Sandusky.

When spring arrived they were still seething at the desecration

of their graves at Prophetstown. Tecumseh was travelling

throughout the northwest rebuilding his confederacy. Although he

preached a pan-Indian confederacy to stop American aggression

his message was tempered with a plea to hold back until the time

was right. But the war chiefs had trouble holding back some of

their young warriors.

The melting snows turned into the worst outbreak of violence

the frontier had seen in fifteen years. Thanks to governor

Harrison First Nation warriors were no longer congregated in

one place. Now they were spread out in a wide arc from Fort

Dearborn (Chicago) to Lake Erie. They were striking everywhere

at once. In January the Winnebago attacked the Mississippi lead

mines. In February and March they assaulted Fort Madison

killing five and blockading it for a time. In April they killed two

homesteaders working their fields north of Fort Dearborn. That

same month five more settlers were killed along the Maumee and

Sandusky Rivers with one more on Greenville Creek in what is

now Darke County.

The Kickapoo were just as busy. On the 10th of February a

family by the name of O’Neil was slain at St. Charles (Missouri).

Settlers in Louisiana Territory were in a state of panic. Potawatomi

warriors joined in. April saw several attacks in Ohio and Indiana

Territory. Near Fort Defiance three traders were tomahawked to

death while they slept in their beds while other raids were made

on the White River and Driftwood Creek.

200 David D Plain

On the 11th of April two young warriors named Kichekemit

and Mad Sturgeon led a war party south burning a house just

north of Vincennes. Six members of a family named Hutson along

with their hired hand were killed. Eleven days later it is believed

that the same Potawatomi party raided a homesteader’s farm

on the Embarras River west of Vincennes. All of the Harryman

family including five children lost their lives.

The frontier was ablaze with retribution for Prophetstown and

settlers were leaving the territories in droves. Governor Edwards

complained that by June men available for his militia had fallen

from 2,000 to 1,700. A militia was raised by each of the Northwest

Territories for protection. At times American First Nation allies

were caught in the middle. Two friendly Potawatomi hunters were

killed near Greenville and their horses confiscated. Both Governors

Edwards and Louisiana Governor Benjamin Howard called for a

new campaign against their antagonizers but the Secretary of War

was occupied with the clamoring for war with Great Britain and

its accompanying invasion of Upper Canada.

The raids on settlers stopped as quickly as they started. By

May the warriors committing the atrocities declared their anger

over grave degradation at Prophetstown was spent. Tecumseh’s

coalition had gelled in the Northwest. In the south the Red Sticks

had taken ownership of his vision and had become extremists

acting on their own and not really part of his confederacy. The

stage was now set for a major war. In June of 1812, while General

Hull and his army of 2,000 hacked their way through the

wilderness to Detroit Tecumseh sent a small party of his followers,

mostly Shawnee, to Amherstburg while he traveled south to visit

Fort Wayne.

From Ouisconsin to Caughnawaga 201

The Detroit Theater

Tecumseh arrived at Fort Wayne on June 17, 1812. He met

with the new Indian Agent Benjamin Stickney and stayed three

days discussing their relations with the Americans. He laid the

blame for all the unrest in the spring at the feet of the Potawatomi

and informed Stickney he would travel north to Amherstburg to

preach peace to the Wyandotte, Ottawa, Potawatomi there as well

as the Ojibwa of Michigan. Stickney was new but no fool. He did

not believe him so he told Tecumseh that a visit to Amherstburg

could only be considered an act of war considering the two

colonizers were so close to going to war themselves. Tecumseh left

Fort Wayne on June 21st not knowing that the United States of

America had declared war on Great Britain on June 18, 1812.

Earlier that spring General Hull assembled an army in

Cincinnati. In May he marched them to Dayton where he

added to his forces before continuing on to Urbana. Meanwhile,

Governor Meigs also called for a conference at Urbana with chiefs

friendly to the U.S. The purpose was to secure permission for

Hull to hack a road through First Nations’ land to Fort Detroit.

This new road would also serve as a supply line for the American

invasion force.

Tarhe spoke for the Wyandotte and Black Hoof for the Ohio

Shawnee. Their speeches were followed by harangues by other

chiefs including the Seneca chief Mathame and the Shawnee

Captain Lewis. Captain Lewis had just returned from Washington

and like the others declared their undying fidelity to Americans.

They not only gained permission for the road but permission also

to build blockhouses at strategic places along the way. Captain

Lewis and Logan also agreed to act as interpreters and scouts for

General Hull. The long and arduous trek to Michigan began.

While Hull slowly trudged through the dense forests of Ohio

and Michigan the other governors of the Northwest Territories

202 David D Plain

arranged for another conference at Piqua with friendly First

Nations. One was planned for August 1st and included groups

of Miami, Potawatomi, Ottawa and Wyandotte. The Americans

assumed that when war broke out a few groups might flee to

Canada and join Tecumseh’s forces but the majority would

remain neutral. They were expecting 3,000 First Nations people.

The conference was designed to keep them neutral with the

combination of presents and supplies along with an expectation

that the size of Hull’s forces and its reinforcement of Detroit would

overawe them. But, Hull’s over-extended journey left supplies short

and the presents failed to arrive on schedule so the conference was

postponed to August 15th. Meanwhile British agents spread the

rumor that the conference was a ploy designed to get the warriors

away from their villages where American militia would fall upon

them killing their women and children.

Tecumseh took ten of his warriors and left for Amherstburg on

June 21st. He planned to join the warriors already sent on ahead.

They skirted Hull’s lumbering army arriving at Fort Malden at the

end of the month.

Amherstburg was a small village some seventeen miles south of

the village of Sandwich on the Canadian side of the Detroit River.

Located at the north end of the village was a small, dilapidated

outpost called Fort Malden. It was poorly maintained and under

garrisoned. Although over the previous two months it had been

tripled it still only amounted to 300 regulars from the 41st

Regiment of Foot and one detachment of Royal Artillery. There

were also 600 Essex Militia available but they were insufficiently

armed and most were without uniforms. They were mostly farm

boys from the surrounding homesteads who had no real interest in

fighting but only joined the militia for a Saturday night out.

The infantry was commanded by the able Scot Captain Adam

Muir. Lieutenant Felix Troughton had command of the artillery.

Lieutenant-Colonel Thomas Bligh St. George, who had overall

command, stationed 460 militiamen along with a few regulars

directly across the river from Detroit to protect the border. They

settled in at the village of Sandwich to meet the invasion.

From Ouisconsin to Caughnawaga 203

Directly in front of Amherstburg was a large heavily wooded

island called Bois Blanc. There had been Wyandotte and Ottawa

villages there since the founding of Detroit over 100 years earlier.

The island provided a place for the numerous encampments of

other warriors who had begun to gather in the area. A large main

council lodge was erected opposite the island on the mainland

near the village’s small dock yard. The dockyard provided slips

for the three British ships that commanded Lake Erie; the brig

Queen Charlotte, the schooner Lady Prevost and the small ship

General Hunter.

When Tecumseh arrived he found his warriors joining in war

dances with the others. Near the council lodge warriors would

give long harangues detailing their exploits in previous battles

striking the war post with their war clubs and working themselves

into a frenzy. The drums would begin their loud rhythmic

pounding and the dancing warriors would circle their sacred

fire all the while yelling their blood curdling war whoops. The

garrison would respond with cannon salutes. Soldiers would shout

out cheers while they fired their rifles into the air from the rigging

of the three ships.

Although the din of the warrior’s preparation for war was

impressive their numbers were not. They were mostly Wyandotte

from the Canadian side under Roundhead, his brother Splitlog

and Warrow. Tecumseh was present with his thirty Shawnee.

War Chief Main Poc was there with a war party of Potawatomi.

The contingent of warriors also included thirty Menominee, a

few Winnebago and Sioux, sent by the red headed Scottish trader

Robert Dickson from Green Bay. The Munsee Philip Ignatius was

also present with a few from the Goshen mission at Sandusky. The

number was rounded out by a sprinkling of Ottawa, Ojibwa and

Kickapoo. On July 4th a large war party of Sac arrived to bring

the total warrior contingent to 350.

Canada was looking decidedly the underdog. Only 300

British regulars, 600 ill equipped militia and 350 First Nation

warriors protected the Detroit frontier. Hull was approaching with

an army of 2,000 and the Americans were raising another large

204 David D Plain

invasion force in the east to attack at Niagara. And there would be

no help arriving from England because of the war in Europe.

The general population of Upper Canada was a mere

77,000 with many of them recent American immigrants. Their

loyalty was questionable. The population of the U.S. Northwest

Territories was 677,000. The American Congress had approved

a total allotment of over 180,000 fighting men. General Brock

was looking at a war on two fronts with only 1,600 regulars and

11,000 militiamen at his disposal. Tecumseh had sent out many

war belts as a call to arms but the large and powerful Three Fires

Confederacy’s feelings were that they should remain neutral. They

saw no reason to get involved in a war with the Americans that

did not look winnable. Only a few young hotheads such as Ojibwa

warriors Wawanosh, Waboose or The Rabbit, Old Salt and Black

Duck from the St. Clair had joined Tecumseh at Amherstburg.

Canada’s prospects were looking very grim!

Hull Invades Canada!

General Hull finally arrived at Detroit on July 6, 1812. He was

in overall command of his forces while Lieutenant-Colonel James

Miller commanded the veterans of Tippecanoe, the 4th Regiment

of United States Infantry. Also with him was the 1,200 strong

Ohio Militia under Lewis Cass, Duncan McArthur and James

Findlay. The Michigan Militia joined him there raising his total

force to over 2,000 fighting men.

This impressive show of American strength had the Canadian

side of the Detroit in a panic. Canadian militiamen began

deserting in droves. Their rolls quickly dropped from 600 to

less than 400. Townspeople began to flee inland taking what

From Ouisconsin to Caughnawaga 205

they could with them. Some communities such as Delaware sent

overtures to Hull on their own. Canadian civilians were not the

only citizens to be apprehensive about the prospects of war in

their own environs. Six months earlier the settlers of Michigan

Territory sent a memorial to Congress pleading for protection from

perceived threats from the surrounding First Nations. In it they

claimed it was not the British army they feared, however they did

not trust them for protection against attacks by “the savages”.

The invasion came on July 12th. American troops crossed

the Detroit and occupied Sandwich. The few British regulars and

what was left of the Essex Militia defending the border quickly

scrambled back to Fort Malden. On the 13th Hull crossed over

to make his proclamation to the Canadians. He entered Canada

presenting himself as a glorious liberator. All citizens who

remained neutral would be treated kindly and their property

respected. However, anyone found to be fighting beside and

“Indian” would receive no quarter but “instant destruction would

be his lot”.

In an area of wetlands and tall grass prairie laid the only

defensible position between Amherstburg and Sandwich. About

five miles north of Fort Malden a fairly wide, slow moving stream

meandered toward the Detroit. There was a single bridge which

crossed the Aux Canard connecting the only road between the two

villages. On July 16th it was protected by a few regulars with two

pieces of artillery and about fifty warriors.

Suddenly, Lewis Cass and his Militia along with a few

American regulars appeared at the bridge. Cass positioned a few

marksmen on the north side of the river while he took the rest of

his 280 men upstream to find a ford to cross over. Meanwhile,

his riflemen picked off two British soldiers killing one. When he

arrived back at the bridge on the south side of the Aux Canard

he overwhelmed the warriors and their British counterparts. Shots

were fired by both sides but there were few casualties. The warriors

and their contingent of British regulars wheeled their artillery away

and retreated back to Malden.

206 David D Plain

The Americans had tasted their first real military success at

the Aux Canard as Sandwich was given up without a fight. But

this victory was short lived. That night the warriors preformed

a loud, boisterous war dance on Amherstburg’s wharf to prepare

for the expected upcoming battle. The next day Roundhead led

his Wyandotte warriors north up the road to the bridge. Main

Poc followed with his Potawatomi while the rest were under

Tecumseh’s command. To their utter amazement the Americans

had abandoned the bridge and were retreating back up the road

to Sandwich. They retook the bridge and moved the Queen

Charlotte upstream to the mouth of the Aux Canard to provide

cannon cover. While the soldiers ripped up the bridge except for a

few planks and built a rampart on the south side of the stream the

warriors hounded the Americans with wasp like sorties until they

withdrew from Canada to the safety of Fort Detroit.

General Hull was a much older soldier that he had been in

the American Revolution Then he had been daring and far more

decisive. He had grown much more cautious and vacillating in

his old age. Not only was he indecisive but he had developed an

extraordinary fear of native warfare. In fact the warriors terrified

him. It was him that ordered Cass to retreat much to the chagrin

of his men. Now he sat day after day in war council trying to

determine what to do next. But nothing was ever decided. He

fretted about the security of his supply line from Ohio and he

imagined far more warriors surrounding him than the few that

were at Amherstburg. His men, including his officers, began to

complain bitterly behind his back.

On the day after the American Invasion while Lewis

Cass retreated to Detroit the small American post, Fort

Michilimackinac, at the head of Lake Huron fell. It had come

under attack by the British Captain Charles Roberts who had

393 warriors with him. They included 280 Ojibwa and Ottawa

warriors from Superior country as well as 113 Sioux, Menominee

and Winnebago braves recruited by Robert Dickson from

those who had been loyal to Tecumseh and Main Poc. That

most northerly fort was lightly garrisoned and ill equipped so it

From Ouisconsin to Caughnawaga 207

capitulated without a shot being fired. The warriors were on their

best behavior that day attested to by Mr. Askin Jr. who wrote, “I

never saw a so determined people as the Chippewas and Ottawas

were. Since the capitulation they have not drunk a single drop of

Liquor, nor even Killed a Fowl belonging to any person (a thing

never Known before) for they generally destroy everything they

meet with”.

When Hull received word of the fall of Michilimackinac

it only added to his anxiety. He envisioned hordes of “savages”

descending on Detroit from the north. He sent dispatches back

to Eustis begging for more reinforcements to be sent to provide

protection from the 2,000 war-whooping, painted, feathered

warriors he imagined approaching from the north.

While Hull fretted and vacillated back and forth Duncan

McArthur moved his men back down the dusty road to the Aux

Canard. As he advanced he kept encountering pesky bands of

warriors. The warriors were so determined that they forced the

Americans back. In one skirmish Main Poc was shot in the neck

and had to be helped from the field. He later recovered. In another

skirmish McArthur who was retreating had his men turn and fire

upon the pursuing warriors. A story later sprang up that when the

volley was fired the warriors all hit the ground face first except

one who remained defiantly on his feet. That one was reportedly

Tecumseh!

The Invasion Stalls

Hull worried about his supply line from Ohio. He was also

convinced he was outnumbered by fierce, unrelenting warriors.

Anxious to keep “his friendly Indians” in Michigan Territory

208 David D Plain

neutral he called for an all native conference to renew their pledges

of neutrality. Captain Lewis, Logan and The Wolf acted as scouts

for Hull when he hacked his way through the bogs of northwestern

Ohio and dense forests of Michigan to Detroit. Black Hoof joined

them just after their arrival. Hull assigned them the task of calling

the friendly chiefs to a council at Walk-In-The-Water’s Wyandotte

village near Brownstown. Tecumseh, Roundhead and Main Poc