Week 3: Dodem System

Five Main Dodems

The Anishnaabeg had no central government, so the two things that held the nation together were a common language and the family. Dodem is the Anishnaabemowin (Ojibwe language) word for the system used for keeping track of family lines. Dodems usually take the form of an animal, bird or fish. The English phrase clan system often substitutes for dodem system, as does the word totem for dodem. A person would make their mark by drawing their dodem. These marks or drawings were accepted by colonial governments as signatures.

One traditional story of how the dodems were received is when the Anishnaabeg lived as one huge nation on the Atlantic seaboard. Six spirit beings came out of the sea to bring the people gifts of knowledge. One of them was different than the other five. His eyes glowed, and if he gazed upon a human being, that person would fall dead. So the others enticed him to return to the sea. The five gave the people the teaching of the dodem system. The Anishnaabeg received five main dodems; Crane, Bear, Fish, Marten and Bird. Today, there are many dodems under each main dodem. For example, under the Fish dodem, there are Catfish, Pike, Sucker, Sturgeon and Whitefish.

Dodem Societal Functions

Each of the five main dodems symbolized a function of society that was required. The Crane dodem represented leadership, chiefs. The Bear embodied defence or police, the Fish intellectuals or teachers, the Marten warriors and the Bird spiritual leaders. The function of an individual’s dodem does not dictate his station in life. For example, if one is born into the Crane dodem but is better suited to healing, they will become healers. As additional dodems developed, each carried the societal function of their main dodem. This teaching has variations in different regions of Anishnaabeg lands. In some stories, the number of original dodems is seven.

Rules

The rules for the dodem system were straightforward. Children took their dodem from their biological father. A person kept their dodem for life. For example, women did not take their husband’s dodem when marrying. Marrying within the same dodem was forbidden. Generally, if a person’s father does not have a dodem, they would be adopted into the Marten family. However, this situation is handled differently in some regions.

The Anishnaabeg have no distant relatives. People with the same dodem and from the same generation are considered brothers or sisters. If from above uncles or aunts or below nephews or nieces. Families treat visitors with the same dodem as close relatives. For example, they give them gifts, lodging, food and water even if they are, by Western conventions, distant relatives and not personally known.

Viewing Assignment 1

View the following two videos. Note the differences in the practices between various regions. There is no right or wrong method. The idea is to take away the teaching given in the tradition, not the empirical facts.

Also, note the similarities and differences between the Anishnaabeg Dodem System and the Ho-Chunk Clan System from the second video of week two (Andy Thundercloud.)

Questions

Besides being assigned to the Marten dodem, how can people whose father has no dodem know theirs?

If an individual cannot trace his lineage back to a forefather that signed a document with a dodem, what other way is available?

What is the difference between a personal name and a dodem?

Colonial Impact

In the early 19th century, the colonial government began systematically trying to assimilate the indigenous population. Missionaries were hard at work proselytizing whole reserves and were generally successful. The settler government followed up by passing legislation that outlawed indigenous cultural practices and traditions. Indigenous populations abandoned the dodem system favouring the Western approach, which continued for several generations. In the late 20th century, a return to traditionalism occurred. Individuals wanted to know their dodem, but many had lost this knowledge.

In southwestern Ontario, there was a period between the late 18th century and the late 19th century when indigenous leaders signed many documents with a name and a dodem mark. If an individual wanted to know their dodem could trace their genealogy back to one of these signatories, they could discover it. The following are successful examples of this method.

Example 1 – Audrey Jacobs

An Anishnaabe-kwe (Ojibwe woman) wanted to know her dodem. She could trace her paternal lineage back to her great-great-great-grandfather Quakegon, one of the chiefs who signed Treaty #29 with the Colonial Government in 1827.

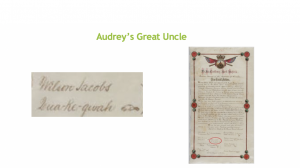

https://recherche-collection-search.bac-lac.gc.ca/eng/Home/Record?app=FonAndCol&IdNumber=3963075 last viewed February 18, 2022. Audrey could also locate her grandfather’s brother’s signature, including dodem on a document from 1874. Wilson Jacobs also traces his lineage back to Quakegon.

Example 2 – Dionne Maness

In this example, a young man traced his paternal lineage back to his great-great-grandfather, an Englishman. Because his paternal forefather had no dodem, he was assigned the Marten dodem.