4

These are difficult stories. We bear witness in this chapter to the role of sport in furthering the settler colonial projects throughout Turtle Island. Here are some supports to access in the community and from a distance:

First Peoples House of Learning Cultural Support & Counselling

Niijkiwendidaa Anishnaabekwag Services Circle (Counselling & Healing Services for Indigenous Women & their Families) – 1-800-663-2696

Nogojiwanong Friendship Centre (705) 775-0387

Peterborough Community Counselling Resource Centre: (705) 742-4258

Hope for Wellness – Indigenous help line (online chat also available) – 1-855-242-3310

LGBT Youthline: askus@youthline.ca or text (647)694-4275

National Indian Residential School Crisis Line – 1-866-925-4419

Talk4Healing (a culturally-grounded helpline for Indigenous women):1-855-5544-HEAL

Section One: History

A) The Residential School System

Exercise 1: Notebook Prompt

We are asked to honour these stories with open hearts and open minds.

Which part of the chapter stood out to you? What were your feelings as you read it? (50 words)

| The Indian Act:

The employment of recreation and sports as integration tactics in residential schools was one aspect of Chapter 15 that particularly caught my attention. Although they were frequently presented as chances for enjoyment or discipline, they were actually regulated and controlled in order to repress Indigenous identities and uphold colonial norms. Seeing how something as seemingly constructive as sports was used to foster cultural erasure was quite unnerving. I felt troubled and thoughtful after reading this portion; it brought home to me how every element of Indigenous children’s existence was designed to sever their ties to their culture, community, and identity.

|

B) Keywords

Exercise 2: Notebook Prompt

Briefly define (point form is fine) one of the keywords in the padlet (may be one that you added yourself).

|

First approved in 1876, the Indian Act is a federal law in Canada that regulates issues pertaining to Indigenous peoples. It establishes who is considered a “Status Indian” and governs a number of facets of their existence, including as government, education, and land. Through detrimental measures like residential schools and prohibitions on cultural traditions, the Act was designed to subjugate and integrate Indigenous peoples into Euro-Canadian civilization. Many people see it as a representation of colonialism and systematic oppression, despite the fact that it has undergone changes over time. Because it still has an impact on Indigenous rights, identity, and self-determination in Canada, the Act is still divisive.

|

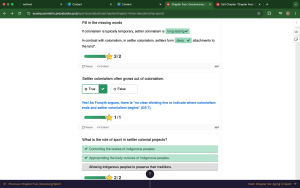

C) Settler Colonialism

Exercise 3: Complete the Activities

Exercise 4: Notebook Prompt

Although we have discussed in this module how the colonial project sought to suppress Indigenous cultures, it is important to note that it also appropriates and adapts Indigenous cultures and “body movement practices” (75) as part of a larger endeavour to “make settlers Indigenous” (75).

What does this look like? (write 2 or 3 sentences)

| A colonial tactic to justify their presence on stolen land is the notion that settlers are “becoming Indigenous” by appropriating and adapting Indigenous customs and body movement practices. Without consent or cultural awareness, settlers frequently appear to be appropriating Indigenous symbols, rituals, attire, or customs—such as sweat lodges, drumming, or smudging. Traditional games may be incorporated into sports and leisure activities in ways that deprive them of their cultural significance, or Indigenous iconography (such as mascots) may be used. These actions, which continue to disregard Indigenous sovereignty and lived realities, are about asserting a sense of belonging to the land rather than about respect or healing.

|

D) The Colonial Archive

Exercise 5: Complete the Activities

Section Two: Reconciliation

A) Reconciliation?

Exercise 6: Activity and Notebook Prompt

Visit the story called “The Skate” for an in-depth exploration of sport in the residential school system. At the bottom of the page you will see four questions to which you may respond by tweet, facebook message, or email:

How much freedom did you have to play as a child?

What values do we learn from different sports and games?

When residential staff took photos, what impression did they try to create?

Answer one of these questions (drawing on what you have learned in section one of this module or prior reading) and record it in your Notebook.

| How much freedom did you have to play as a child?

Systemic impediments, colonial practices, and intergenerational trauma have influenced Indigenous children’s childhoods in Canada, particularly historically and in many cases presently. Indigenous communities have been severely damaged by the Sixties Scoop, residential schools, and persistent disparities in access to clean water, healthcare, education, and housing. Racism, inadequate services, and a system that, in many respects, still polices and controls their identities and destinies are common challenges faced by Indigenous children as they grow up. An affluent white child – like myself and most children I grew up with – on the other hand, usually has a lot more freedom as they grow up, the freedom to travel, to dream, to get good healthcare and education, and to see their identity positively represented in institutions, the media, and national narratives. Rather than being watched and controlled, their families frequently profit from systemic support and generational wealth. Playing, pursuing interests like sports or the arts without doubting their place, and believing that the structures in their environment are meant to support and encourage them rather than to stifle or absorb them are all examples of this freedom. That sense of comfort and inclusion is not assured for Indigenous children. An Indigenous child is much too frequently compelled to provide, defend, or survive, whereas the privileged white child frequently has the opportunity to simply, be. The enduring effects of colonialism and the necessity of genuine reconciliation, justice, and equity are shown in this glaring disparity.

|

B) Redefining Sport

B) Sport as Medicine

Exercise 7: Notebook Prompt

Make note of the many ways sport is considered medicine by the people interviewed in this video.

|

C) Sport For development

Exercise 7: Notebook Prompt

What does Waneek Horn-Miller mean when she says that the government is “trying but still approaching Indigenous sport development in a very colonial way”?

| When Waneek Horn-Miller claims that the government is “trying but still approaching Indigenous sport development in a very colonial way,” she is drawing attention to the fact that, despite their best intentions, government initiatives frequently continue to function within frameworks that do not adequately respect or represent Indigenous leadership, autonomy, or worldviews.

Approaches that stress Western values above Indigenous knowledge and practices, impose external control, and adopt a one-size-fits-all model are referred to as “colonial ways.” For instance, initiatives could be developed for Indigenous communities instead of with them, disregarding their input during the decision-making process. They might prioritize rivalry above community or undervalue sport’s cultural and spiritual significance in Indigenous cultures. In order to empower Indigenous communities to design, direct, and finance their own sports programs, Horn-Miller is advocating for a change from merely integrating Indigenous athletes into mainstream systems. This entails giving Indigenous governance, values, and cultural practices a central place in the creation of sport and acknowledging sport as a source of identification, healing, and cultural survival in addition to being a physical activity. Her remarks serve as a reminder that structural transformation, not merely superficial inclusion, is necessary for genuine healing. |

Exercise 8: Padlet Prompt

Add an image or brief comment reflecting some of “binding cultural symbols that constitute Canadian hockey discourse in Canada.” Record your responses in your Notebook as well.

In Canadian hockey discourse, the outdoor rink is a potent unifying cultural image that stands for pride in the country, nostalgia, and the notion that anyone can become a great hockey player from modest beginnings. It connects the sport to the Canadian winter environment and is idealized as a place of belonging, resiliency, and identity. But this image also symbolizes a settler narrative that frequently leaves out marginalized and Indigenous populations, whose representation in hockey and access to such arenas have historically been restricted. The outdoor rink is beloved by many, but it also shows who is central to, and excluded from, the prevailing narrative of Canadian hockey.

|

Section Three: Decolonization

Please see the major assignment for this half of the term in the final section of this chapter.

LONGER PROMPT FOR THIS CHAPTER:

All levels of government are urged to guarantee long-term assistance for the development of Indigenous athletes and to guarantee the inclusion of Indigenous peoples in Canada’s sports programs under Action 88 of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission’s (TRC) Calls to Action. The federal government has taken steps to start achieving this, including national initiatives, collaborations, and investments that support Indigenous participation in sports at the community and elite levels.

The Indigenous Sport Program (ISP), which promotes community-based sport development for Indigenous youth, is one significant project. This includes initiatives that give athletes the chance to compete in a setting that is culturally affirming, such as the North American Indigenous Games (NAIG) and the Aboriginal Sport Circle. Funding for NAIG and other initiatives has been continuously supplied by the government. The bilateral agreements between provinces and Sport Canada serve as another illustration; these agreements frequently contain clauses pertaining to inclusive infrastructure, coaching development, and Indigenous sport initiatives.

The government’s funding of the 2023 NAIG, which brought together thousands of Indigenous children from all around North America to participate in a variety of sports while honouring their cultures, is one particular example. These gatherings offer chances for cultural pride, community development, and reconciliation in addition to athletic competition.

By supporting Indigenous-led sports groups, learning about and going to Indigenous sporting events, and fighting for fair access to facilities and resources, communities and individuals, especially settlers, can make a difference. By addressing preconceptions and cultural appropriation, settlers may also consider how mainstream sports venues frequently marginalize or exclude Indigenous athletes and seek to create more inclusive places. It is crucial to establish sincere connections with Indigenous communities and respect their autonomy when creating and running sports programs. Additionally, settlers can educate themselves on the colonization history of sport and leisure and strive to guarantee that Indigenous perspectives are at the forefront of these discussions.

Sport may promote reconciliation by fostering an environment that supports Indigenous leadership, cultural expression, values, and voices. Recognizing the ability of sport to empower, heal, and unite communities is necessary to support this Call to Action. Settlers may contribute to the development of a more equitable and respectful environment that supports Indigenous athletes and communities by listening, learning, and acting as allies.