5

Section one: The fundamentals

A)

Exercise 1: Notebook Prompt

Many of you are likely familiar with the concept of “ability inequity,” which the authors of this article define as “an unjust or unfair (a) ‘distribution of access to and protection from abilities generated through human interventions’ or (b) ‘judgment of abilities intrinsic to biological structures such as the human body’.”

However, they go on to identify the following “ability concepts” that are less familiar:

1) ability security (one is able to live a decent life with whatever set of abilities one has)

2) ability identity security (to be able to be at ease with ones abilities)

How prevalent are these forms of security among disabled people you know? Or, if you identify as a disabled person, would you say your social surroundings and community foster and support these kinds of security? Furthermore, while the focus of the article is on Kinesiology programs, it is also important to reflect on how academia in general accommodates for disability. If you feel comfortable answering this question, what has been your experience of postsecondary education to date?

-OR-

The authors also observe that “Ableism not only intersects with other forms of oppression, such as racism, sexism, ageism, and classism, but abilities are often used to justify such negative ‘isms’.”

What do you think this means? Provide an example.

| The quote means that society often uses assumptions about ability to justify other forms of discrimination. For example, people from racialized or low-income backgrounds might be seen as less capable in school or work, not because of their actual abilities but because of biased expectations. Similarly, women may be labeled too emotional to lead, or older adults may be seen as unable to adapt—showing how ableism reinforces racism, sexism, ageism, and classism.

|

Exercise 2: Implicit Bias Test

Did anything surprise you about the results of the test? Please share if you’re comfortable OR comment on the usefulness of these kinds of tests more generally.

| I was a little surprised by the results of the test. I didn’t expect to show any bias, but it made me realize how easily unconscious ideas can slip into our thinking—even when we don’t mean any harm. I consider myself to be open and supportive of people with disabilities, but this test reminded me that there’s always room to grow. I think these kinds of tests are useful, not because they define who we are, but because they push us to reflect on what we’ve picked up from society without even realizing it. It’s a good starting point for deeper conversations and change.

|

B) Keywords

Exercise 3:

Add the keyword you contributed to padlet and briefly (50 words max) explain its importance to you.

| Keyword: Inclusion Inclusion matters to me because it’s about making sure everyone feels seen, valued, and supported, especially those who are often left out. It’s not just about access but also about creating spaces where all people, regardless of ability, can fully participate and thrive without judgment or barriers.

|

B) On Disability

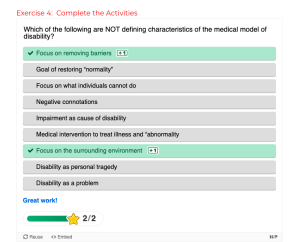

Exercise 4: Complete the Activities

Exercise 5: Notebook Prompt

What do Fitzgerald and Long identify as barriers to inclusion and how might these apply to sport in particular?

- Fitzgerald and Long identify several barriers to inclusion that are especially relevant in the context of sport. One major barrier is the persistence of negative attitudes and assumptions about disabled people, which are often shaped by ableism and low expectations. These attitudes can lead to exclusion rather than meaningful participation. Physical barriers, such as inaccessible facilities or equipment not designed with diverse needs in mind, also limit opportunities for disabled athletes. Additionally, the way sport is structured often reinforces segregation, with disabled athletes placed in separate or “special” programs rather than being integrated into mainstream teams and competitions. There is also a lack of representation of disabled individuals in leadership or coaching roles, which contributes to a lack of understanding and inclusive practices. Together, these barriers make it difficult for disabled athletes to access equal opportunities and feel fully included in the world of sports.

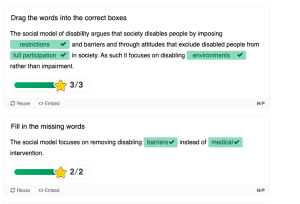

C) Inclusion, Integration, Separation

[

[

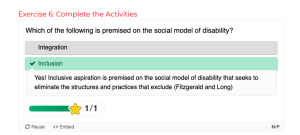

Exercise 6: Complete the Activities

Exercise 7: Notebook Prompt

Choose ONE of the three questions Fitzgerald and Long argue disability sport needs to address and record your thoughts in your Notebook.

- Should sport be grouped by ability or disability?

- Is sport for participation or competition?

- Should sport competitions be integrated?

| I think sport competitions should be integrated, but only if the environment is truly inclusive and adapted to support everyone equally. Integration shouldn’t just be about placing disabled and non-disabled athletes in the same space—it needs to involve changing rules, equipment, and attitudes so that disabled athletes are valued and not tokenized. Without these changes, integration can feel superficial or even exclusionary. True integration means equal respect, opportunity, and recognition for all athletes, regardless of ability.

|

Part Two: Making Connections

A) Gender, Sport and Disability

Exercise 8: Complete the Activity

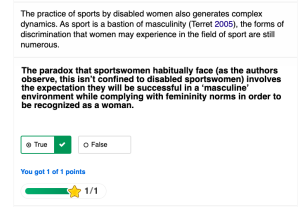

The paradox that sportswomen habitually face (as the authors observe, this isn’t confined to disabled sportswomen) involves the expectation they will be successful in a ‘masculine’ environment while complying with femininity norms in order to be recognized as a woman.

True or false?

Take a moment to reflect on this paradox below (optional).

| This paradox forces sportswomen to constantly balance strength with femininity, making them work twice as hard to be taken seriously and still “fit in.” |

B) Masculinity, Disability, and Murderball

Exercise 9: Notebook/Padlet Prompt

Watch the film, Murderball and respond to the question in the padlet below (you will have an opportunity to return to the film at the end of this module).

The authors of “Cripping Sport and Physical Activity: An Intersectional Approach to Gender and Disability” observe that the “gendered performance of the wheelchair rugby players can…be interpreted as a form of resistance to marginalized masculinity” (332) but also point out that it may reinforce “ableist norms of masculinity.” After viewing the film, which argument do you agree with?

a) Murderball celebrates a kind of resistance to marginalized masculinity

|

d) Murderball does both of these things. Murderball both resists and reinforces ideas of masculinity. On one hand, it challenges the stereotype that disabled men are weak or dependent by showcasing strength, aggression, and competitiveness in wheelchair rugby. This visibility resists the marginalization of disabled masculinity and reclaims power and pride. On the other hand, the way masculinity is performed in the film often mirrors traditional, able-bodied norms—like toughness, emotional restraint, and dominance—which can reinforce ableist expectations about what it means to be a “real man.” So, while the film is empowering in many ways, it still operates within a narrow definition of masculinity.

|

Section Three: Taking a Shot

A) Resistance

B) Calling out Supercrip

Exercise 10: Mini Assignment (worth 5% in addition to the module grade)

1) Do you agree with the critique of the “supercrip” narrative in this video? Why or why not? Find an example of the “supercrip” Paralympian in the 2024 Paris Paralympics or Special Olympics coverage and explain how it works.

|

Yes, I agree with the critique of the “supercrip” narrative. While stories of disabled athletes overcoming adversity can be inspiring, they often reduce individuals to their disabilities and frame their achievements as extraordinary solely because of their impairments. This perspective can inadvertently perpetuate ableist notions by implying that success is exceptional for disabled individuals, rather than recognizing their accomplishments on equal footing with non-disabled peers. An example from the 2024 Paris Paralympics is the portrayal of Marcel Hug, a Swiss wheelchair racer. Media coverage frequently emphasized his “mechanical perfection” and extraordinary speed, highlighting his disability as a central aspect of his success. While Hug’s achievements are undoubtedly remarkable, focusing primarily on his disability rather than his athletic prowess reinforces the supercrip narrative. It suggests that his accomplishments are noteworthy mainly because he is disabled, rather than celebrating his dedication, training, and skill as an elite athlete. This type of representation can overshadow the broader systemic issues affecting disabled individuals and place undue pressure on them to achieve exceptional feats to be valued.

|

2) Does the film Murderball play into the supercrip narrative in your opinion? How does gender inform supercrip (read this blog for some ideas)?

(300 words for each response)

|

The film Murderball both challenges and reinforces the supercrip narrative. On one hand, it offers a raw and authentic portrayal of wheelchair rugby athletes, emphasizing their athleticism, competitiveness, and personal lives beyond their disabilities. This depiction moves away from the traditional supercrip trope that often portrays disabled individuals as heroic solely for overcoming their impairments. By focusing on the athletes’ dedication to their sport and their interpersonal relationships, the film humanizes them and presents disability as just one aspect of their identities. However, Murderball also reinforces certain aspects of the supercrip narrative. The athletes are often depicted as embodying hypermasculine traits—aggressiveness, toughness, and dominance—which align with societal ideals of masculinity. This portrayal suggests that to be respected and valued, disabled men must conform to these norms, effectively “overcoming” their disabilities by proving their masculinity. Such representations can inadvertently marginalize those who do not or cannot conform to these standards, reinforcing ableist and gendered expectations. Gender plays a significant role in shaping the supercrip narrative. In Murderball, the focus is exclusively on male athletes, highlighting their physical prowess and competitiveness. This emphasis on traditional masculine ideals suggests that disabled men can reclaim their masculinity through sport. Conversely, disabled women often face the double burden of overcoming both ableist and sexist stereotypes. They are frequently expected to maintain femininity while also demonstrating resilience, a balance that is rarely demanded of their male counterparts. This disparity underscores how gender informs and complicates the supercrip narrative, highlighting the need for more diverse and inclusive representations of disability in media.

|