Session 2: ‘Race’ in the Middle Ages

Learning Objectives

The students will be able to:

- Critically assess the representation and treatment of a character in medieval texts

- Give a working definition of race (based on Critical Race Theory and its applications in medieval studies)

- Name some of the arguments in the debate around medieval race

Introducing a Critical Approach to Race

If this is taught in German, the students should be made aware that English ‘race’ and German ‘Rasse’ have different connotations and very different histories. You may choose to use either as long as this is clearly justified and explained.

- How does Geraldine Heng define the concept of race in the introduction to The Invention of Race?

See pp. 19 and 27, particularly the latter.

The working definition below is similar to Heng’s, if slightly simpler, and reflects the approach taken by many other scholars of pre-modern race:

Race essentialises a physical or cultural trait, meaning that it makes the trait the unchangeable core identity of those who display it. This trait is expected to be linked to moral traits or other kinds of traits, and leads to a value judgement.

Confirm that the students understand this definition by asking them to apply it to something that has no particular connotations or implications: detached vs. undetached earlobes.

Earlobes can be detached, semi-detached or undetached. There is no proved connection to the person’s character, abilities, origins, or anything else either concrete or abstract that might have any impact on that person’s life.

- Apply the above definition of race to detached earlobes to test out your understanding of the concept.

For example, people with detached earlobes might become ‘the Detached’. This would become their main feature and would be thought to be connected to other, negative traits: loud, disruptive and dangerous, bad music tastes, etc. In general, the Detached would be considered inherently and permanently inferior to people with semi-detached earlobes, who might themselves be slightly inferior to people whose earlobes are undetached. In any case, there would be real-life consequences for people with detached earlobes as well as everyone else.

Discussion of Heng’s Introduction

- Share first impressions of the reading (difficulty, first reactions…)

- Share the one idea, question or citation which stood out to each reader, with room to comment on each other’s responses.

Work on summarising the chapter together, going over the main arguments for and against a concept of medieval race which are mentioned in each section. Then open up the discussion, for example by asking how this debate fits into the students’ prior knowledge of the Middle Ages.

Application and Reading the Second Moriaen Passage

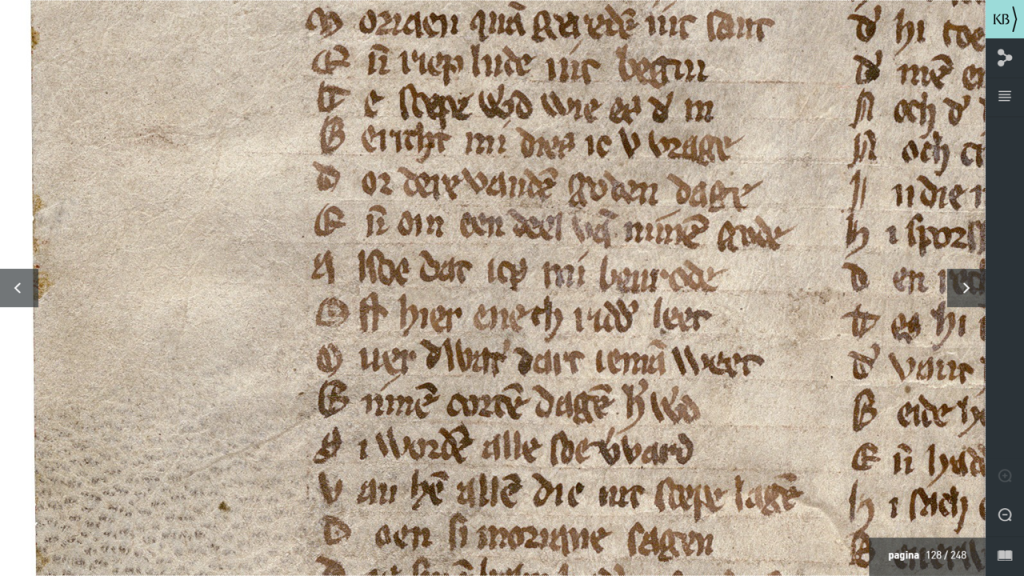

Link to the digitised manuscript of Moriaen, Royal Library of the Netherlands

This is a good opportunity to introduce the students to the digitised format and show them what the site can do and how to use it.

Note the visible pores on the parchment!

- Transcribe a few lines of this passage.

Recording of the 2nd passage:

Opportunity to review some of the linguistic elements taught in session 1:

- How come there are both English and German words and phrases written in the margin of the PDF?

Middle Dutch is related to both of these languages, remember the Germanic sandwich!

- Translate the first page.

- Read the whole passage.

Here is the translation of the first page of this passage:

Moriaen came riding in the sand and shouted loud in the direction where the ships were: ‘Whoever is in there, tell me this which I ask you in the name of God’s days and in exchange for part of my belongings, so I can be satisfied, if any knight was led over there across the water from here recently, so that one can know.’

Then, when they saw Moriaen who had taken off his helmet, all those who were on the boats were terrified of him. He could not hear nor understand any word or answer. They were immediately terrified, since he was black and large.

Each turned his boat seaward and left the shore, for Moriaen looked as if he hard come out of hell. They thought they had heard the devil who wanted to torment them here. The one who was able to leave him first did not want to wait for the others.

- How is Moriaen described in this passage? Compare with the first passage.

- When reading this, who do you relate to and support the most? To understand how the reader’s empathy and compassion are guided throughout, analyse the passage by marking any changes in focalisation.

- What is the narrator’s position on the issue of Moriaen being denied passage across the sea?

- Remember that Moriaen eventually becomes an Arthurian knight and fulfils his quest by bringing his father back with him to marry his mother and live in Moriane. What questions could you ask or how could you analyse the text to find out more about whether his dark skin is racialised, i.e. whether the idea of race is useful here?

This question is useful to encourage the students to think about the research process and develop their own essay writing skills, as well as digging deeper into the question of medieval race as an analytical tool. It is best answered after a short preparation time, or in pairs, or as a class discussion. Possible answers include (some of these questions may also be worth discussing at greater length!):

Does Moriaen become integrated as a knight? How complete is his success? What does the narrator have to say about this? For whom exactly and when is it a problem that he is black, when/how is this overcome? How important is it that he is a Christian? And a Moor (which, as explained above, has several other connotations beyond black skin)? Is it important that he is the only Moor in the text? (there is no description of the mother). What does it mean that he is the main character in an Arthurian romance? Is the reader encouraged to view Moriaen as an example to be followed and imitated? etc.

Conclusion: Dealing with a Wide Range of Representations

Many of these questions remain unanswered for the moment. However, other texts might treat black characters very differently even if they were written and read at a similar time and place. Therefore, a more general question to ask when discussing medieval race is: does race need to appear in all texts in order to be a prominent concept of the time? How do we handle the great variety of representations that characterises much medieval literature? What is most representative – individual poets, genres like Arthurian romance, or linguistic groupings like medieval ‘German’ and ‘Dutch’ literature?

The question of course expands beyond literature to most aspects of culture. Art, like literature, has its own conventions and specificities in how it represents things and people, but there are also some similarities.

- Describe and compare the black figures in the images featured on pp. 17, 19 and 43 of Heng’s introduction. Look for example at their clothing, size, features, attitude and gestures, the level of exoticism or not, etc. The image of the queen of Sheba on the Verdun altar, on p.188 in the book, offers another interesting perspective.

- How do they compare to the white-skinned figures you might have come across in other medieval artworks?

- What do they tell us about the context in which Moriaen was written, where does the main character fit in?

Medieval writers had their own opinions and motivations which shaped how they presented black, Jewish, and other non-normative characters. While the issue of race in medieval literature continues to be hotly debated and a lot of additional research will be needed to make sense of these very different perspectives, it certainly proves useful, as we have seen, to enquire about a text’s treatment of black and otherwise racialised characters in ways that are informed by contemporary Critical Race Theory. Power dynamics between characters, along with other details of characterisation and narrative perspective as well as narrative structure are all highlighted in the process. Hence, this approach is rapidly gaining in popularity.

Suggestions for a Longer Module

- After the discussion of images of black figures, you may wish to introduce the black Saint Maurice, who was popular in much of northern Germany in the 13th and 14th centuries. The famous Magdeburg statue of Maurice shows him as a knight too: the representations of Maurice and Moriaen have much in common. There is a useful overview of the history and scholarship around the black Saint Maurice on the website Black Central Europe.

- For an advanced and more confident group of students, comparisons with the depictions of black characters in better-known Middle High German texts could also be made, in particular with Feirefiz in Wolfram von Eschenbach’s Parzival, where there is considerably more extant research as well as a good English translation.