Session 1: Black Knights in the Dutch Middle Ages

Learning Objectives

The students will be able to:

- Situate Middle Dutch in relation to other medieval European languages and literatures

- Recognise and read short passages of Middle Dutch

- Critically assess the representation and treatment of a character in medieval texts

Warm Up

| Text 1:

Daventure doet ons gewach: Des margens, alst was dach, Voren si wech alle beide Menege wustine, menege heide Ende hoge berge ende dale Om te vindene Perchevale; Maer dat pine jegen spoet: Sine mochtens niet wesen vroet. Des hadden si menech swaer verdrach. |

Text 2:

Ane valsch dû reiner, Dû drî unt doch einer, Schepfaere über alle geschaft, Âne urhap dîn staetiu kraft Ân ende ouch belîbet. Ob diu von mir vertrîbet Gedanke, die gar vlüstic sint, Sô bistû vater unt bin ich kint, Hôch edel ob aller edelkeit. |

- Which words or sentences do you understand?

- Can you spot any differences in how the two texts look (spellings, syntax) or sound (pronunciation)?

- Which passage is in Middle High German, and which one is in Middle Dutch?

Recording of Text 1:

Recording of Text 2:

The first passage is Moriaen, V.409-417, Middle Dutch. The second is Willehalm, Wolfram v. Eschenbach, I,1-9, Middle High German.

Introduction to the Middle Dutch Language

Middle Dutch was used over a similar period as Middle High German (1050-1450), although with a slightly later beginning: from about 1160 or 1170 to 1500. German, Dutch and English are often described as forming a linguistic continuum known as the ‘Germanic Sandwich’. This means that Dutch, including Middle Dutch, is a sort of halfway point between the linguistic features of German and English, and it shares elements of both languages as well as having its own peculiarities. Like Middle High German and many other medieval languages, Middle Dutch can be divided into several dialects, some closer to German and others closer to English: Flemish, Zeelandic, Brabantian, the dialect of the region of Holland, and Limburgian.

- In Text 1, do you recognise any words or phrases that are similar in German and English?

Words similar to German words are shown in red, those similar to English are in green.

One of the crucial aspects of the continuum is the second or High German consonant shift.

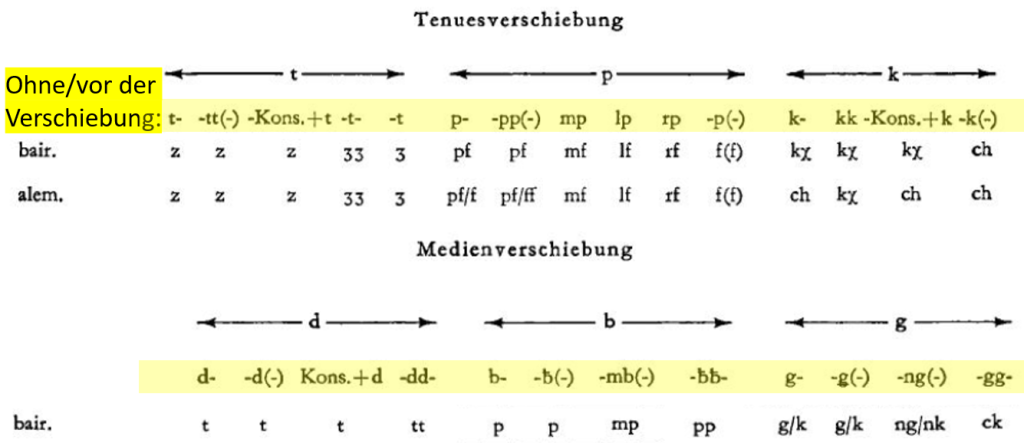

For students who are already familiar with the High German consonant shift:

- What do you know about the second consonant shift? Cite some examples of words that are different in modern English and German due to the way German consonants have shifted. Do you remember some of the consonants that changed and what they became?

Then proceed to the table below for a detailed review.

For students not familiar with the shift:

Suggest some words in English and German, like ‘pepper’/’Pfeffer’, ‘dead’/’tot’, which sound similar yet have different consonants. Can the students think of any other words like these? These are often words that were either useful or confusing to them when learning German vocabulary. Then use the table below to introduce the shift, which differentiates German from all the other Germanic languages. The top line represents unshifted consonants like those found in Dutch, whereas Old Bavarian and Alemannic are given as examples of fully shifted German dialects.

For example, in verse 413 ‘dale’ is similar to modern German ‘Tal’, meaning ‘valley’. In German, /d/ in the initial position in a word has shifted to /t/, whereas the Dutch word has kept its original form. In verse 424, ‘tande’ is a cognate of modern German ‘Zähne’, where the initial /t/ has shifted to /z/. The distinction between shifted versus unshifted consonants is the main difference between German and Dutch.

PDF of the full passage: Moriaen vv. 409-489 with a new English translation (see note on translations of Moriaen in the Additional Resources)

- Find 10 more examples of words in the full text PDF whose German equivalents have shifted consonants. It might help to focus only on 3 consonants to narrow down the search.

- How are Middle Dutch and Middle High German related, and how do they differ? The students can partner up and summarise what they have just learnt by explaining it to each other. This will also help them identify any questions or uncertainties that remain about this section of the lesson.

Introduction to Middle Dutch Literature

The literary centres of the medieval Dutch world were mostly located in the southern parts of the region. Antwerp and Amsterdam were becoming increasingly important locations for trade, which in turn allowed them to establish themselves as centres of literary production. The dialect of Holland therefore gained great momentum, and was later to become the basis of modern Dutch – although like all dialects, it was itself influenced by its neighbours, Brabantic and the other southern dialects, as linguistic boundaries much like political ones were fairly porous in this period. We know also that Middle Dutch literature was strongly influenced by French courtly literature, and to a lesser extent by German literature. In any case, texts like Moriaen, which shares several motives with Wolfram von Eschenbach’s famous 13th century Grail romance Parzival, illustrate perfectly the combination of reception of prominent literary ‘trends’ and innovation which characterised Middle Dutch literature.

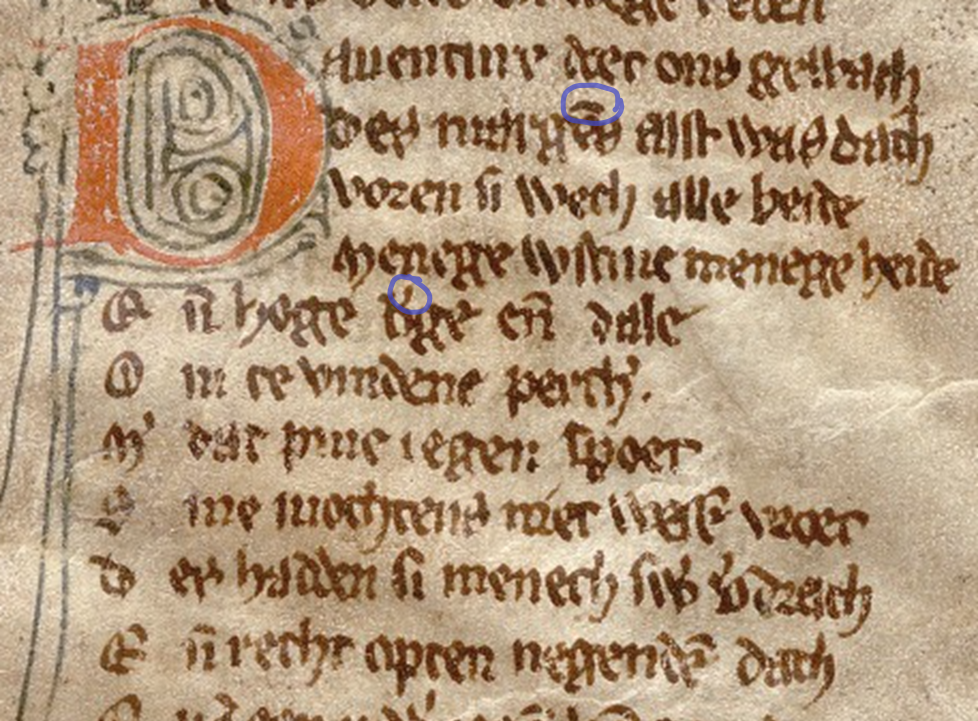

Moriaen, our core text here, was first composed in Flemish sometime after 1250. Today, the full text only survives in one 14th century manuscript known as the Lancelot Compilation. As its name indicates, this manuscript is a collection of Arthurian texts retracing the adventures of Lancelot. While some aspects of Moriaen hark back to the French, German and possibly also English Arthurian traditions, there is no known surviving source from which it might have been translated, and it is therefore currently considered a Middle Dutch original.

Here is the same section of the text in the digitised manuscript. The scribe has followed the common convention of using abbreviations for ‘n’ (and adjacent letters, like in the word ‘ende’) in the form of a horizontal line above a letter (the ‘Nasalkürzung’) and for ‘er’ as an apostrophe (‘‘er’-Kürzung’).

- Have a go at reading these few lines. It might help to compare what you see against the text provided above.

Plot summary of Moriaen:

At the beginning of the tale, the dark-skinned knight Moriaen travels to Arthur’s kingdom to find his father, the knight Aglovael. He meets Walewein (Gawain) and Lanceloet and tells them his family’s story: after a brief romance with the black princess of the country of Moriane, the fictional ‘land of the Moors’, Aglovael was forced to return to Arthur’s court. The princess, who had become pregnant, was rejected by her family, so that her son Moriaen grew up without the advantages of his rank. Touched by this story, Walewein and Lanceloet decide to help Moriaen. Arriving at a crossroads, the three knights split to explore the different paths and Moriaen sees footprints leading to the shore which he suspects are his father’s. When he asks to be taken across the sea, the ferrymen run away thinking that Moriaen is the Devil, so he goes back to find his companions. The ensuing adventures show that Moriaen is at least as great a knight as the other two: he saves Walewein from being executed, and Lanceloet from being killed by a monster. Together they return to the ferrymen and trick them into letting them board the boat. On the other side of the sea, the three knights finally find Aglovael recovering from a series of battles. Aglovael agrees to return to Moriane and marry Moriaen’s mother. While Aglovael rests, Moriaen helps to free Arthur who has been captured by the king of Ireland. Arthur thanks and publicly praises Moriaen, who finally leaves with Aglovael for the country of Moriane.

From the very beginning, Moriaen is described in very positive terms by the narrator. Yet in spite of being an accomplished knight, he encounters many difficulties and hostile reactions from other characters due to the colour of his skin. This discrepancy is the central issue of these learning materials.

About ‘Moors’ (‘Mohren’ in German), the name ‘Moriaen’ and the country of ‘Moriane’: The protagonist is explicitly connected to the stereotypical category of the ‘Moor’, which was widespread across much of this period’s literature. Similarly to the term ‘Saracen’, this category is not clearly delineated and encompasses a variety of stereotypes. ‘Moors’ are often exoticised non-Christian black people who are believed to live in a distant land in North Africa. As we will see, Moriaen is a great example of the flexibility of this category.

Reading and Analysing the Passage

Recording of the whole passage:

After a quick demonstration, possibly using the recording, the students can read through the rest of the Middle Dutch text aloud, then read the translation.

Pronunciation tips: ‘g’ sounds like the hard ‘ch’ in modern German ‘acht’; ‘w’ sounds like English ‘w’ in ‘woods’.

- How is Moriaen described? Find the exact words that are used.

- Discussion: does he seem to fit the ideal of the courtly knight? (e.g. in terms of manners, appearance, kit, physical prowess, knowledge, beliefs…)

In some aspects, yes, in others he at the very least stands out: he is well equipped but too aggressive, prays to God and admires the most famous knights of Arthur’s court but is unusually tall and, of course, his skin is black instead of the glowing pale skin which is a sign of the nobility of many Arthurian knights and ladies.

- How do Walewein and Lanceloet react and respond to Moriaen? How would you describe the exchange that takes place between them?

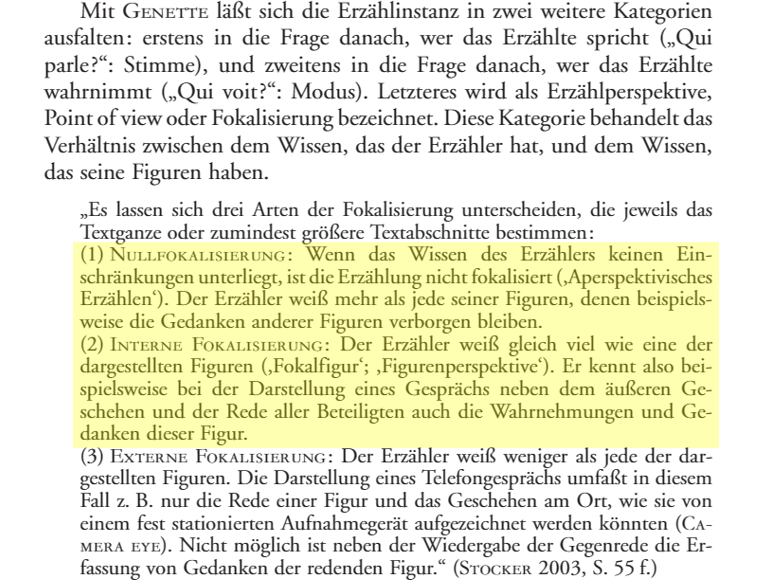

Now let’s look more closely at how the text is structured. This passage of Moriaen incorporates a variety of different perspectives.

- Identify the different perspectives and make a note when the focalisation switches.

- What are the opinions expressed by the narrator here?

- Based on what you have found, what might happen next in the text?

Ask the students to read the introduction to Geraldine Heng’s book ahead of the next session. To encourage them to engage with this fairly challenging reading, you can ask them to prepare an idea, question or citation from the introduction that stood out to them. The students should also attempt to read the second passage of Moriaen. While there are dictionaries and other resources they could use to prepare a translation of this text, it is most productive and a better use of their time to work through the translation in class.

Heng, Geraldine. “Inventions/Reinventions: Race Studies, Modernity, and the Middle Ages.” The Invention of Race in the European Middle Ages, Cambridge University Press, 2018, pp. 15–54.