5

Section one: The fundamentals

A)

Exercise 1: Notebook Prompt

Many of you are likely familiar with the concept of “ability inequity,” which the authors of this article define as “an unjust or unfair (a) ‘distribution of access to and protection from abilities generated through human interventions’ or (b) ‘judgment of abilities intrinsic to biological structures such as the human body’.”

However, they go on to identify the following “ability concepts” that are less familiar:

1) ability security (one is able to live a decent life with whatever set of abilities one has)

2) ability identity security (to be able to be at ease with ones abilities)

How prevalent are these forms of security among disabled people you know? Or, if you identify as a disabled person, would you say your social surroundings and community foster and support these kinds of security? Furthermore, while the focus of the article is on Kinesiology programs, it is also important to reflect on how academia in general accommodates for disability. If you feel comfortable answering this question, what has been your experience of postsecondary education to date?

-OR-

The authors also observe that “Ableism not only intersects with other forms of oppression, such as racism, sexism, ageism, and classism, but abilities are often used to justify such negative ‘isms’.”

What do you think this means? Provide an example.

| Sport officials and higher ranking decision makers, in regards to sporting programs, are under responsibilities to adhere to the hard work done in the creation of initiatives, including inclusive standards for sport in regards to inclusion practices. These mandates are not being followed, and furthermore seem to be, not only ignored, but further perpetuated. Ableism is hidden under the justification of other negative ‘isms’ in the idea of this is just the way sports is and always will be. Diversity is especially important within sports, at a very human and fundamental level as it “facilitates group cohesion”, and underrepresentation for certain groups in sports leads to “further segregation of these groups”. This is a long-standing lack of inclusion for example, felt in females. There is deep-rooted assumption in the ability of females in sports, which growing up kept something like sports, a very enriching and team-building process in early development, out of reach for girls and those perceived as smaller and unable. In order to combat this type of thinking, mandates are not enough to change the attitudes of long-standing educators assimilated into teaching a certain way, and we need training programs that physical education teachers must complete before they are eligible and confident in generating inclusion in the classroom. Changing the attitudes has to come from the initial stages of educator development.

|

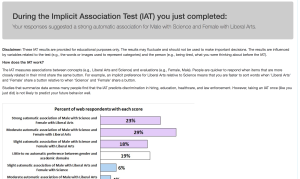

Exercise 2: Implicit Bias Test

Did anything surprise you about the results of the test? Please share if you’re comfortable OR comment on the usefulness of these kinds of tests more generally.

The aspect that particularly surprised me about the test was the fact that you can have a strong illicit response to certain biases, while still realizing how silly and obvious to where these biases come from. You can be very aware of it, while still speeding through, just going to show how much work to break down these biases will, but the barriers that come from it, are so realizable.

|

B) Keywords

Exercise 3:

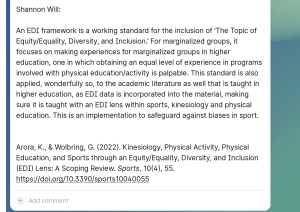

Add the keyword you contributed to padlet and briefly (50 words max) explain its importance to you.

EDI Framework: An EDI framework is a working standard for the inclusion of ‘The Topic of Equity/Equality, Diversity, and Inclusion.’ For marginalized groups, it focuses on making experiences for marginalized groups in higher education, obtain an equal level of experience in programs involved with physical education/activity. This standard is also applied, wonderfully so, to the academic literature as well that is taught in higher education, as EDI data is incorporated into the material, making sure it is taught with an EDI lens within sports, kinesiology and physical education. This is an implementation to safeguard against biases in sport.

Arora, K., & Wolbring, G. (2022). Kinesiology, Physical Activity, Physical Education, and Sports through an Equity/Equality, Diversity, and Inclusion (EDI) Lens: A Scoping Review. Sports, 10(4), 55. https://doi.org/10.3390/sports10040055

|

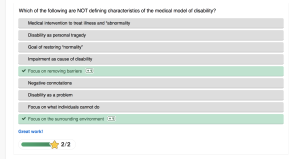

B) On Disability

Exercise 4: Complete the Activities

Exercise 5: Notebook Prompt

What do Fitzgerald and Long identify as barriers to inclusion and how might these apply to sport in particular?

In regards to sport, inclusion is of particular importance due to its developmental nature of the activity at such a crucial age for youth, and that includes ALL youth. Sport can come in various shape and form, because at its root, it is about physical activity and competition with one’s self, and at its merit, the “contribution to the common good”, that everyone deserves. In this breath, what is crucial but one of the largest challenges is implementation, and the encouragement of “sports organizations and government agencies to subject their claims of fairness, merit, entitlement and inclusion to scrutiny.” These organizations, whom are reluctant to change, also “argue for the lion’s share of resources on the basis that their excellence.” Putting this type of funding into jeopardy, and fear of a change in the status quo, is very hard to break down initially but can be done through education at the root. This involves educating educators, and promoting wider participation in programs that educate about contributing factors leading to under-representation. This includes “low incomes; long working hours; religious observance; shortage of facilities in areas with large minority ethnic populations; language barriers; and racism.” It is very difficult to tackle, but one could start with resource allocation because “inequality per se also matters and requires a narrowing of the gap between rich and poor,” and changing the attitudes of being selfish and short-sighted with these resources, including attention and care, to students in the world of physical education, specifically.

C) Inclusion, Integration, Separation

Exercise 6: Complete the Activities

Exercise 7: Notebook Prompt

Choose ONE of the three questions Fitzgerald and Long argue disability sport needs to address and record your thoughts in your Notebook.

- Should sport be grouped by ability or disability?

- Is sport for participation or competition?

- Should sport competitions be integrated?

| Should sport competitions be integrated?

Sport competitions should be integrated due to the overwhelming benefits of doing some things a little bit differently. Especially in larger competitions that are on the world stage, an integrated league would give organizations the opportunity to reshape; to meet the needs of these new standards and demands. In regards to sports and the societal factors surrounding it, in Miller’s left-liberal view of ‘fair distribution’, he does have some merit in trying to include an organizational structure that includes “a correction of market outcomes through redistribution to improve the position of the least advantaged up to the minimum standard.” He points to the advantages of a diverse workforce including adequate representation in decision-making bodies, which would empower people of minority groups, including disabled people to facilitate activities and needs that help breach the gaps between non-disabled people and disabled people.

|

Part Two: Making Connections

A) Gender, Sport and Disability

Exercise 8: Complete the Activity

The paradox that sportswomen habitually face (as the authors observe, this isn’t confined to disabled sportswomen) involves the expectation they will be successful in a ‘masculine’ environment while complying with femininity norms in order to be recognized as a woman.

True or false?

Take a moment to reflect on this paradox below (optional).

| I personally find that women in professional roles, such as those breaking down those barriers and becoming women coaches is amazing. In basketball for example; seeing those beautiful women in professional gorgeous suits, is amazing. However, it does beg the question here, that in a men’s environment, it is definitely notable how compliant these women are being in adhering to femininity roles in order to be recognized as a woman, and the power as a woman in the suit. What truly bugs me though, is the fact that the male coaches, almost unanimously nowadays (trust me, I’ve looked), are wearing three-quarter zip-ups, and at least half, are wearing jogging pants. It makes sense for a second, in a sporting environment, a sporting get-up, but these are the coaches, whose title merits a suit, in respect of the title and the position held. The women coaches are respectfully wearing suits, as the leading member of the team, the representation of the team, but the male coaches are not doing this. They have gotten lazy in their position. |

B) Masculinity, Disability, and Murderball

Exercise 9: Notebook/Padlet Prompt

Watch the film, Murderball and respond to the question in the padlet below (you will have an opportunity to return to the film at the end of this module).

The authors of “Cripping Sport and Physical Activity: An Intersectional Approach to Gender and Disability” observe that the “gendered performance of the wheelchair rugby players can…be interpreted as a form of resistance to marginalized masculinity” (332) but also point out that it may reinforce “ableist norms of masculinity.” After viewing the film, which argument do you agree with?

a) Murderball celebrates a kind of resistance to marginalized masculinity

| After viewing the film ‘Murderball’, and dissecting what I can of the intricate factors going into being a top-level wheelchair rugby athlete, I would find myself agreeing with option A. I think that the thing that ‘Murderball’ does best is showing the film in a documentary style that is equally focused on the absolutely regular lives that these men live, while playing at very top-level capabilities. It is their job and passion, doing the same thing abled bodied athletes are doing with such praise. ‘Murderball’ shows a resistance to marginalized masculinity however “the deconstruction of certain stereotypes can thus contribute to the reinforcement of others.” Murderball is refreshingly vulnerable about the connotations in which it takes to be a disabled athlete, and the main point of the film is completely against what audience expectations are to be. The film does not show how resilient these men are being against their disabilities. It rather shows that these disabilities are real, unchanging, and most importantly not a hindrance in succeeding and living regularly; as well living in triumph, albeit it may not come in forms used to by the general public. This idea is encompassed by Crip Theory; that it can “de-compartmentalize identities to show their multiplicity, and in doing so, it participates in the deconstruction of gendered and ableist categories.

|

Section Three: Taking a Shot

A) Resistance

B) Calling out Supercrip

Exercise 10: Mini Assignment (worth 5% in addition to the module grade)

1) Do you agree with the critique of the “supercrip” narrative in this video? Why or why not? Find an example of the “supercrip” Paralympian in the 2024 Paris Paralympics or Special Olympics coverage and explain how it works.

| I critique this video and the ‘supercrip’ narrative in it, because it perpetuates the narrative of disabled people as being in a separate category of people than non-disabled people, and they do not have to be. There is such a separation of disabled people, as many under-assume the independence that a large portion of the population of disabled people can have and range in. Areas in which they cannot be independent, athletes have found that if there are accommodations to where help is needed, there is no reason as to why disabled athletes cannot achieve the same feats as the athletes we see on TV all day long, are performing.

The term ‘supercrip’ actually undermines what these athletes are doing, and is giving the “perception that the achievements of athletes with disabilities mean they are overcoming and transcending their disabilities” (Loeppky, 2023). In this category of thinking that stems from ableist roots, it is focusing their narrative into a way that all disabled people can achieve this, and that these people are completely different than ‘normal’ people, “rather than just being athletes in general…and that’s the thing that we kind of need to go away” (Loeppky, 2023). John Loeppky goes on to explain that as a community, “ableism continues to be something that I and many in the para-sport community are still reckoning with” (Loeppky, 2023) and within this, there are cases of disabled athletes using the narrative of ‘supercrip’ as a temporary band-aid of sorts, as “a way to insulate themselves from the more brazen ableism outside the athletic world” (Loeppky, 2023). This critique is not of the idea that disabled athletes can do great things and should such think of themselves with great potential the same as every person, but from the idea of painting athletes in the ‘Supercrip’ narrative as these special beings, is not really helping disabled athletes come to terms with their situation. This is something the documentary does very well in addressing, as it shows the men as regular beings and not as superheroes of the sport, but that their success truly comes through incredible resilience and a little help from friends. As well, Loeppky describes the trend of athletes being biased in status within themselves, also highlighting the complexity of the situation of these athletes, as some are “taking personal offense to being called a Special Olympian versus a Paralympian and . . . I think if you unpack that, that certainly does stem from ableist roots, for sure” explains Loeppky. Overall, the critique of the narrative ‘Supercrip’ is generally a plea to treat disabled athletes with the proper respect as any other human being, and being aware specifically to the biases still imposed on them, in the name of being ‘inclusive.’ To treat them like the regular people involves treating them with the same amount of assumptions one would a regular athlete, in that they may triumph or they may fail. It is not a winning story narrative like the ‘Supercrip’ one. It is also “radically exclusionary to many with disabilities” (Loeppky, 2023) to be at the level of top level of Paralympians and Special Olympians. This is as much out of reach for the regular joe to as it is the regular disabled person. In a reality where potential is realized on both sides, on realistic and levels you can root for, perhaps we can even reach a regular norm of seeing athletes in disabled leagues “transitioning into coaching and officiating roles” (Loeppky, 2023). This is currently extremely uncommon to see, unlike the way it is the norm for non-disabled leagues to see athletes’ transition into these roles. This is another example as to why I agree that this video paints these athletes into a category of pure triumph for the sake of inclusion, which skews their own and the audience’s perceptions of the sport, not basing them into reality at all.

Works Cited

Grappling with Ableism in the Para-Sport Movement. (2023, June 13). Rooted in Rights. https://rootedinrights.org/grappling-with-ableism-in-the-para-sport-movement/

|

2) Does the film Murderball play into the supercrip narrative in your opinion? How does gender inform supercrip (read this blog for some ideas)?

(300 words for each response)

| Does the film Murderball play into the supercrip narrative in your opinion? How does gender inform supercrip (read this blog for some ideas)?

(Incorporated in answer above ^^ but also below )

Shannon Will 0648025 April 15, 2025 GESO 3134 Major Assignment #2

Murderball A Sport as Impressive as the Rest

The documentary ‘Murderball’ is a poignant and demanding representation of the U.S. Quadriplegic World Rugby team, as they face off against Canada, led by past teammate, fellow quadriplegic, and tenacious fighter Joe Soarse. The story unfolds as a representation of diversity in a sport relatively underrepresented, showing impressive feats parallel to the great athletes. The representations of masculinity and disability present themselves documentary-style. The film follows the U.S. team battling through a hard season, working through grief and angst, with pride in their abilities. They redefine expectations of disabled athletes through challenging misconceptions about ability, exploring their motivations and aptitude, and showing how media depiction, common misconception and systematic challenges present themselves. Work can be done systematically to shift expectations of disabled players and their feats.

When it comes to preconceived concepts and representations, portrayal of disabled sports lacks a full and honest review of the realities of the athletes. Often, it is the “violence and the juxtaposition of masculinity and disability instead of just aggressiveness in sport” (Cottingham, Gearity, Goldsmith, Kim, & Walker, 2015), that is shown when it comes to disabled leagues. Many do not know enough about their abilities, and the playing level these athletes are on, to treat them with the proper respect. The capabilities are just as profound as very top athletes, as disabled athletes have found a way to re-accustom the sport. This potential is as lucrative as any other human, shown in the film through an impressionable statement that “any attempts to try to point to the wheelchair or the accident as the cause of his grumpiness would be an utter hoax” (Rubin & Shapiro, 2005, 6:03), speaking on the normality of misassumptions. It can be seen throughout the film how “social expectations are so low for individuals with a disability that any positive action may induce praise from others” (Chatfield & Cottingham, 2017). This praise may even in times be inspiring to non-disabled athletes, but this inspiration is used for “greater initiative in their respective fields and that improvements in competitiveness of a men’s university wheelchair basketball team resulted in a program that continued to inspire those who wanted to compete on an elite level but ‘alienated the broader disability community’” (Chatfield & Cottingham, 2017).

The film depicts this pre-conceived ignorance with immediacy, as the film opens with Mark Zupan, a Paralympian wheelchair rugby player, dressing himself with effort; a shot that shows the constant wide-ranging effects of his disability, stretching to common things that have become a far different experience than the average. He retorts this idea however with statements of reality, reminding the audience, “What am I supposed to be/ in a closet hanging out? (Rubin & Shapiro, 2005, 2:10), “You’re not gonna hit a kid in a chair? Fucking hit me. I’ll hit you back” (Rubin & Shapiro, 2005, 2:40). These men are not any less adept and tenacious as top athletes in the world, and deserve to take up as much space as the rest. A problem lies in the promotion of the sport. The platforms for “disability sport promoters are constrained by razor-thin budgets and typically lack formal marketing departments” (Cottingham, Gearity, Goldsmith, Kim, & Walker, 2015). The cumulative effects of this contributes to “normalizing a spectrum of oppression, from daily microaggressions to systemic inequality” (Harrison, Azzarito, & Hodge, 2021). Platforms that give little screen time to disabled leagues, are also undereducated to properly cover the sport, cutting off advancements in recognition for these athletes.

Soares explains how “everyone was curious to how I was going to be, how much function I was going to have” (Rubin & Shapiro, 2005, 1:29). The bodies-at-risk discourse examines how “marginalized groups are blamed for their failure to comply with majorized health norms and physical activity guidelines, and thus, they have increasingly become the problem, the target, and the solution of research interventions” (Wetherly, Watson, & Long, 2017). Personal and physical development, for any being and person, is “a gift that gives for life” (Harrison, et. al., 2021). It promotes good mental health, childhood development, social skills, personal gratification and goal making, and overall, “what it means to be in a team member” (Harrison, et. al., 2021). Sport is a unifying source that is not to be denied, or diminished in the ways in which disabled sports have historically held lesser value and attention in society. This causes underrepresentation, diminishing sponsorship and general promotion of disabled sports, and these are “barriers associated with cultural value systems” (Long, Fletcher, and Watson, 2017). We see these barriers broken down in ‘Murderball’ as it exemplifies through the violence and physical demand of the sport, just how on par wheelchair rugby is, in comparison to popular and widely-watched leagues. “The United States has dominated the sport of wheelchair rugby for the last 10 years” (Rubin & Shapiro, 2005, 6:55), however, due to “westernized economic trends toward competition, homogenization, and sameness” (Wetherly, Watson, & Long, 2017) there maintains an overlook of the “concerns of power, inequality, struggle and ideology, that has, paradoxically, allowed it to be filled with a range of contradictory assumptions that have inevitably spilled back over and into wider society” (Long, Fletcher, and Watson, 2017). This passiveness contributes to the under-assumption of the capabilities of disabled men’s leagues in general, when in reality, quadriplegic rugby is a brutal sport of tenacity through aggression as the original name was coined Murderball, with the sport displaying a “Mad Max wheelchair that can stand getting knocked” (Rubin & Shapiro, 2005, 3:45).

Ableism is challenged in the documentary ‘Murderball’, through a profound lens of the motivations and abilities of the athletes. A form of oppression comes through “judgment of abilities intrinsic to biological structures such as the human body” (Arora & Wolbring, 2022), not only intersecting with “other forms of oppression, such as racism, sexism, ageism, and classism, but abilities are often used to justify such negative isms” (Arora & Wolbring, 2022). The work that must be done to achieve participating in such an aggressive and physically demanding sport, is a tremendous feat in itself. The term ‘supercrip’ is used “to describe media depictions of individuals with disabilities who achieve impressive feats although often these feats would be considered typical for persons without disabilities” (Chatfield & Cottingham, 2017). This is short-sighted and misleading in many ways, as ‘Murderball’ betrays the sheer amount of work needed, from the ground up, to relearn a new normality, and to triumph in that new-normal. The players “have a job to do and it’s been a great ride with Team Canada” (Rubin & Shapiro, 2005, 51:06), expressed the Canadian athletes after a close and hard-fought game, in the end pulling ahead to take the U.S., 24 to 20.

There is need for a complete overhaul of the marketing of disabled leagues because “the athletes have to think ahead so much farther, because just everything changes so quickly,” (Cottingham, Gearity, Goldsmith, Kim, & Walker, 2015), referring to not only the changes on the court, but the transitional life changes and the all the work behind the scenes. These athletes put in as much grief and hard work, and perhaps more, than the celebrity athletes seen everywhere. The division is an unnecessary and diminishing one, with “pre-existing expectations about style of presentation of athlete interest stories” (Chatfield & Cottingham, 2017), focusing on the shortcomings, opposed to the capabilities and successes. The U.S. team describes “using everything [they] have to get through life and that’s what we all have to do, use everything we have (Rubin & Shapiro, 2005, 46:52). ‘Murderball’ shows a whole world of success often unseen and undervalued, with players exclaiming, “if you like football in or any physical sports, then you’ll definitely love wheelchair rugby” (Rubin & Shapiro, 2005, 15:22). Within “11 International competitions, the US has won all of them” (Rubin & Shapiro, 2005, 7:18) with Joe Joe Soares being “arguably the best quad rugby player in the world” (Rubin & Shapiro, 2005, 8:12). If platforms had an educated panel to review disabled leagues with the appreciation of these efforts, disabled leagues could be seen as equally relevant as major leagues, and a celebration of true human effort all the same.

Ability-based marginalization has been affirmed by the disabled community for the better half of a century since “disabled activists and academics coined the term ableism in the United States and Britain during the 1960s and 1970s” (Arora & Wolbring, 2022). According to Arora and Wolbring, in a review of physical education through an EDI lens, “there could, and should, have been much more coverage of the EDI phrases and frameworks than we found” (Arora & Wolbring, 2022). An EDI framework in sports refers to the “narratives around the ability of the body and social role of sports” (Arora & Wolbring, 2022), being conscious about implementing policy in regards to equity, diversity and inclusion. Within EDI frameworks and intersectional policies, disabled sport marketers should “continue to focus on athlete practices and characteristics that potential consumers can connect with. This can counter the discomfort that some individuals have when confronted with disability” (Chatfield & Cottingham, 2017) and begin to actualize these athletes into the same level of normality and appreciation that is seen for non-disabled athletes. ‘Murderball’ encourages an EDI framework implementation at every organization involving sporting activities, to culturally educate and empower teachers and coaches “to develop curricula that respond to students’ cultural differences to bridge cultural gaps and encourage and acknowledge all students” (Wetherly, Watson, & Long, 2017).

The film is pressing in its portrayal of just how much expression and prospect was found to those who took up wheelchair rugby, beguilingly, with as much hesitation as non-disabled people often feel about the sport in general. Joe Soares notes how he “probably would not have had anywhere near the opportunities in life [he’s] had living here in the US… if you’ve got a disability in Portugal, they become ashamed of having someone like such as it is a sign of weakness to them” (Rubin & Shapiro, 2005, 17:15). A progression is shown as Mark Zupan describes how he “even got scared just to get to the newspaper in the morning just cuz I thought people would look at me” (Rubin & Shapiro, 2005, 17:33), to eventually giving credit to his situation. He recalls how “it’s interesting because I’ve actually been able to do more in a chair than I did in an abled body (Rubin & Shapiro, 2005, 59:20)”. He competes at the Paralympics, being a part of a team of the best 12 players of 500 contended. The tenacity of disabled athletes is of such admirable will, it is unreasonable to devalue them through societal demotions of the sport, and true lack of understanding its lengths. Works Cited

Arora, K., & Wolbring, G. (2022). Kinesiology, Physical Activity, Physical Education, and Sports through an Equity/Equality, Diversity, and Inclusion (EDI) Lens: A Scoping Review. Sports, 10(4), 55. https://doi.org/10.3390/sports10040055

Chatfield, S., & Cottingham, M. (2017). Perceptions of Athletes in Disabled and Non-Disabled Sport Contexts: A Descriptive Qualitative Research Study. Qualitative Report, 22(7), 1909-. https://doi.org/10.46743/2160-3715/2017.2483

Cottingham, M., Gearity, B., Goldsmith, A., Kim, W., & Walker, M. (2015). A comparative analysis of factors influencing spectatorship of disability sport: a qualitative inquiry and next steps. Journal of Applied Sport Management, 7(1), 40+. https://link-gale-com.proxy1.lib.trentu.ca/apps/doc/A426149372/AONE?u=ocul_thomas&sid=bookmark-AONE&xid=9f18e73f

Harrison, L., Azzarito, L., & Hodge, S. (2021). Social Justice in Kinesiology, Health, and Disability. Quest, 73(3), 225-244. https://doi-org.proxy1.lib.trentu.ca/10.1080/00336297.2021.1944231

Long, J., Fletcher, T., and Watson, B. (2017) Introducing Sport, Leisure and Social Justice. In Sport, Leisure and Social Justice (1st ed., pp. 1-14). Routledge.

Wetherly, P., Watson, B., & Long, J. (2017). Principles of social justice for sport and leisure. In Sport, Leisure and Social Justice (1st ed., pp. 15–27). Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315660356

|