Julia Christensen Hughes, PhD

The Essentiality of Academic Integrity in an Increasingly Disrupted and Polarized World

Julia Christensen Hughes, PhD

President and Vice-Chancellor

Yorkville University

Introduction

There is no question that higher education has been facing growing pressures for change over the past several years (Christensen Hughes, 2024). Many of these pressures have implications for academic integrity, not just with respect to student academic misconduct (as the term is often narrowly applied), but also with respect to faculty and administrative priorities and practice. In this chapter I argue that it is essential that these pressures and their implications for academic integrity be more fully considered and that a multi-faceted recommitment to integrity be made.

This chapter begins with a review of some of the most daunting pressures for change being experienced within higher education today. Implications for integrity are raised. Next , I present definitions of academic integrity and provide several frameworks for helping guide the work of administrators and faculty towards its achievement. Following, I provide evidence that suggests while we lack comprehensive data on misconduct by faculty and administrators, student academic misconduct may be increasing. I conclude with some suggestions for what academic leaders can do, to enhance integrity within Canadian higher education institutions.

Pressures for Change

Covid-19 and the Rise of Digital Learning

One of the most significant, recent disruptions to higher education has arguably been the Covid-19 pandemic. Beyond concerns with the appropriateness and adequacy of campus health and safety policies (e.g., masking, ventilation, vaccine mandates etc.), has been the ostracization of scientists with “dissenting opinions” (Liester, 2022, p. 53), testing the limits of academic freedom and tenure. Also, as campuses and residences shut down, there was the rapid pivot to on-line learning and assessment. The use of online proctoring technologies has raised “ethical notions of academic integrity, fairness, non-maleficence, transparency, privacy, autonomy, liberty, and trust” (Coghlan et al., 2021, p. 1581).

A survey by the Canadian Digital Learning Research Association (CDLRA) (Irhouma & Johnson, 2022), asked respondents about “the most pressing challenges at their institution related to teaching and learning” (p. 7), as pandemic restrictions were winding down. The “top five challenges were faculty fatigue and burnout (74%), effective assessment practices (61%), effective teaching practices for teaching online (59%), faculty digital literacy (55%), and student fatigue and burnout (50%)” (p. 7).

Despite these challenges, the CDLRA survey also identified an “increased desire for flexible learning opportunities” (p. 25), with Irhouma and Johnson (2022), noting that “scaling back on opportunities to learn fully or partially online limits accessibility” (p. 1). The authors also cautioned, however, that more support was needed, in “technological infrastructure, funding, administrative support, and training to enhance faculty digital literacy” (p. 7).

Effective higher education institutions of the future will be those that challenge the dominant assumption that all students can and should be physically present on campus, as well as the assumption that faculty (by virtue of having a PhD) have the requisite skills for their on-line teaching and assessment responsibilities. Staff who design and support online learning, need to be more fully respected for their expertise and better supported in their essential roles. Concern and support for mental health challenges – of faculty, staff and students – are important additional ethical considerations.

Generative AI and Questions Concerning the Relevance of Higher Education

Relatedly, is the double-edged sword of Generative AI (GenAI) (Berdhal & Bens, 2023) and other advanced AI technologies, that are providing incredible opportunities but are not without risk.

Technology can be an awesome force for good…But today’s AI-powered tools and other emerging technologies can also affect humans in harmful ways—some fuel bias and discrimination, spread disinformation, disregard intellectual property rights, threaten privacy, power autonomous lethal weapons, or possibly pose existential threats to humanity. and integrity (D’Agostino, 2023).

ChatGPT, launched in the fall of 2022, presents a significant challenge to the integrity of traditional university learning assignments, with its ability to instantly synthesize copious amounts of information and produce readable, customizable content, in multiple languages. It can also be used for analysing data sets; producing creative work, such as pictures, songs, poems and videos; writing code; and even evaluating content. We now have the situation where students can submit a personal post or a fully developed paper, and faculty can submit a grade, with neither having actually read the work!

A related concern is the growing obsolescence of what students are expected to learn. A recent study by OpenAI (2023) suggests that occupations which depend on numeracy, programming and writing skills, such as mathematicians, analysts, writers and authors, are most vulnerable to having core elements of their work replaced by AI. Occupations found to be most immune were those requiring a high degree of critical thinking skills. This has important implications for what students should be learning and “how that learning should be facilitated and assessed” (Christensen Hughes, 2023). Large, lecture-based classes combined with assessments that test for recall are becoming increasingly irrelevant. Small classes (in person or online), with applied, skills-based learning activities, which incorporate regular, formative feedback, are what is needed to help students develop a host of ‘future proof’ transferable skills.

In summary, where and what students are learning, how they are being assessed, and the capacity of the faculty to effectively facilitate that learning, is arguably a question of institutional relevance and integrity. Resourcing the innovation being called for is challenging, given long-held institutional funding priorities and strained institutional budgets.

Strained Budgets and Growing International Student Enrolments

Many universities and colleges are experiencing budgetary strain, amidst rising costs and reduced revenues. In Ontario, a Blue-Ribbon Panel recently reviewed the financial sustainability of the sector, recommending increases in tuition and operating grants. Following the release of the Panel’s report, Steve Orsini, CEO of the Council of Ontario Universities (COU, 2023), stated; “The situation is becoming increasingly untenable, as universities can no longer continue to absorb cuts and freezes amidst rising inflation and costs, and many are facing deficits, with the growing risk of insolvencies.” Proving his point, several Ontario universities have recently announced staggering operating deficits, such as Queen’s University, at over $60 million dollars (Evans, 2023).

As one solution to this problem, higher education institutions have pursued growth in international student enrolments. While credible, life transforming opportunities for international students do exist, in alignment with Canada’s immigration priorities, fraudulent activity and sub-standard student experiences are also occurring. Federal Immigration Minister Mark Miller, recently announced changes to the rules concerning international student visas, threatening caps, if conditions don’t improve: “There are, in provinces, the diploma equivalent of puppy mills that are just churning out diplomas, and this is not a legitimate student experience”… “There is fraud and abuse and it needs to end” (Canadian Press, 2023).

Universities and colleges need to pursue new revenue opportunities in ethical ways, ensuring all students receive a quality learning experience and meaningful support.

Research and the Pursuit of Truth

The role of the academy as arbiter of ‘truth’ has also come under question, with faculty research increasingly being found wanting – both for its perceived lack of social relevance (Hoffman, 2016) including weak support for the UN’s Sustainable Development Goals (Nature, 2023), as well as for its untrustworthiness (Christensen Hughes & Eaton, 2022).

According to a recent report in Nature, over 10,000 academic papers were retracted in 2023, a new record (Van Noorden, 2023). Retraction Watch, a not-for-profit organization which has been bringing attention to retracted scientific papers since 2010, has over 50,000 papers in its searchable on-line data base (Retraction Watch, n.d.a), including hundreds concerning the Covid-19 pandemic (Retraction Watch, n.d.b). Of those with a Canadian university affiliation, the reasons for retraction include (Retraction Watch, n.d.a):

Error in Analyses, Error in Results and/or Conclusions, Error in Image, Concerns/Issues About Authorship, Concerns/Issues about Third Party Involvement, Fake Peer Review, Unreliable Results, Concerns/Issues About Data, Concerns/Issues About Results, Manipulation of Images, Duplication of Image, Concerns/Issues about Referencing/Attribution.

Articles highlighting these types of misconduct are becoming more common. As one example, Matusz, Abalkina and Bishop (2023), recently wrote an editorial, in Mind, Brain and Education (MBE), reporting that credible scientific journals are increasingly being targeted and fooled by unscrupulous and sophisticated paper mills, resulting in the publication of work that may include: purchased co-authorships and citations; AI enabled ghost writers; fraudulent peer review; collusion with editors; and “scientific misconduct, including plagiarism, falsification, and fabrication” (Matusz et al., 2023).

In our so called ‘post-truth’ world (Calcutt, 2016), it is essential that society has confidence in the scholarly output of faculty. Scientific integrity is under threat. This assault needs to be addressed with great urgency.

Declining Public Confidence: US

Perhaps not surprisingly, public confidence in higher education appears to be declining, particularly in the US and particularly amongst Republicans (see for example, Wright Dziech, 2023). A recent Gallup poll (Brenan, 2023), found that:

Americans’ confidence in higher education has fallen to 36%, sharply lower than in two prior readings in 2015 (57%) and 2018 (48%). In addition to the 17% of U.S. adults who have “a great deal” and 19% “quite a lot” of confidence, 40% have “some” and 22% “very little” confidence…Republicans’ sank the most — 20 points to 19%, the lowest of any group.

One contributing factor has been its cost. A recent poll by the Wall Street Journal, in collaboration with the University of Chicago’s “non-partisan research group (NORC)”, found that over half (56 percent) of respondents agreed, “a four-year college education is not worth the cost because people often graduate without specific job skills and with a large amount of debt to pay off” (Lederman, 2023). This was up markedly from 40 percent, just ten years ago.

Another criticism has seen the media target ‘left leaning’ faculty, with arguments increasingly being made that university leaders are prioritizing personal political agendas, valuing equity over excellence; pandering to student emotions; cancelling courses, speakers and even faculty who students find “triggering”; and allowing unruliness, when unpopular ideas are presented, preventing meaningful debate (Zakaria, 2023). Relatedly, bills to limit Diversity, Equity and Inclusion (DEI) initiatives have been introduced in several Republican states (Asmelash, 2023).

Jonathan Haidt (2016), Thomas Cooley Professor of Ethical Leadership at the New York University Stern School of Business, has argued for several years that there has been growing tension on American university campuses between “Telos” or “truth” on the one hand and “social justice” or DEI initiatives, on the other (p. 2). In presentations and blog posts, Haidt has suggested a growing “culture of victimhood” has resulted in a state of “moral dependency” and “fragility” amongst students, in which challenging ideas and even select words have become viewed as “violence” (p. 5).

This type of challenge has come into sharp relief, following the brutal October 7th terrorist attack on Israel by Hamas, the war that continues, and the pro-Palestinian protests and antisemitism (hate speech, threats of violence) that has grown precipitously on many American university campuses (Center for Antisemitism Research, 2023).

Concerned, the US Congressional Education and Workforce Committee called for the sworn testimony of the presidents of Harvard University, Claudine Gay, the University of Pennsylvania, Elizabeth Magill, and the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT), Sally Kornbluth on what they were doing to protect their Jewish students (see C-SPAN2-1 and C-SPAN2-2, 2023).

While the presidents strongly condemned antisemitism and shared plans for doing a better job of combatting it, they also argued that the competing goals of “safety” and “free expression” are difficult to balance. This was challenged by expert witness Pamela Nadell, American University, Jewish Studies Program Director; “free speech stands at the core of the liberal arts education…but free speech does not permit harassment, discrimination, bias, threats or violence in any form” (C-SPAN2-1).

Committee member Rep. Tim Wallberg suggested that Harvard’s commitment to free speech was “selective”, citing instances where Harvard faculty had been fired, or forced to resign, when their views were at odds with “campus orthodoxy”. Several house speakers cited Harvard’s last place standing on a Foundation for Individual Rights and Expression (FIRE), College Free Speech Ranking (Stevens, 2023).

In response to a series of questions on whether calls for Israeli genocide (Intifada Revolution) would violate her university’s code of conduct and harassment policies, the president of Harvard stated that while she found such calls “personally abhorrent”, the situation was also “contextual”, and that students wouldn’t be sanctioned unless the speech was directed at particular individuals and there was “conduct that violates policies”. She claimed, while “there’s no place at Harvard for antisemitism…we do not sanction individuals for their political views or their speech.” A similar legalistic stance, citing First Amendment rights, was reiterated by the other presidents (see C-SPAN2-3, 2023).

In the US, hate speech is largely considered “protected speech under the First Amendment” (Moon, 2008, p. 85). Legal opinion, however, suggests that US universities are not prohibited from imposing stricter expectations on hate speech, as some have:

Sensitivity about such speech has grown on many college campuses, public as well as private, and some universities have adopted restrictive guidelines. Many people believe that educational institutions, even those of the state, can set higher levels of civility and respect than the society at large. (Greenawalt, 1992, p. 20)

At the inquiry, in which it became clear that the three presidents had not moved to restrict hate speech on their campuses, Co-Chair Rep. Virginia Foxx concluded:

Post-secondary education has never been held in such low esteem in our country as it is today. I do not refer to colleges and universities any longer as higher education because it is my opinion that higher order skills are not being taught and learned.

She also suggested that the challenge of dealing with antisemitism was heightened, given that it was being carried out by those who “think of themselves as virtuous” and hatred as “righteous” (see C-SPAN2-2, 2023).

Condemnation of the presidents’ testimony on social media was swift. As one example, outspoken Harvard Alumnus Bill Ackman (2023), stated “The presidents’ answers reflect the profound educational, moral and ethical failures that pervade certain of our elite educational institutions due in large part to their failed leadership.” Calls for the resignation of the three presidents followed, with Elizabeth Magill stepping down shortly after. In a video address, she acknowledged that the University’s policies needed to be reviewed; “In today’s world where we are seeing signs of hate proliferating across our campus and our world…the policies need to be clarified and evaluated” (Penn, 2023).The Congressional Committee also announced it would be launching a formal investigation into the three university’s “learning environments” and “policies and procedures” (Borter, 2023). Calls for Gay’s resignation also intensified, along with reports in the media that she had allegedly plagiarized several passages in her doctoral dissertation and other published work (Walker, 2023).

Confidence in Canadian Higher Education: High but Declining

Laws concerning freedom of expression (in Canada) and freedom of speech (in the US) differ. Within Canada, several laws, including the Canadian Criminal Code and Human Rights legislation “prohibit hateful statements”, which have been “upheld as justified limits on freedom of expression” (Moon, 2008, p. 85).

Regardless, an increasing number of antisemitic incidents have been occurring in Canada, including on university campuses, with four Canadian universities – UBC, Queen’s, TMU and York – facing class action lawsuits due to alleged failure to follow “non-discrimination policies” or to provide “sufficient training on handling harassment” (CBC, 2023).

At McGill, the Student Society (SSMU) held a referendum, with almost 80% voting in support of a proposed policy which called for the University’s administration to “condemn a ‘genocidal bombing campaign’ against Gaza and cut ties with ‘any corporations, institutions or individuals complicit in genocide, settler-colonialism, apartheid, or ethnic cleansing against Palestinians’” (The Canadian Press, 2023).

Following a court challenge by a Jewish student, the Quebec Superior Court temporarily blocked the 2023 referendum, and the SSMU agreed to suspend its ratification until a hearing in March. B’nai Brith Canada criticized the University for failing to support Jewish students:

It is sad that a student had to go to the courts for justice on this issue because the university has repeatedly failed to hold its student associations accountable for breaking their own rules…McGill does not have to wait until then to do the right thing. (The Canadian Press, 2023)

At some universities, however, concrete action has been taken. At York, for example, several faculty and staff were placed on leave, after they were charged for allegedly vandalizing an Indigo bookstore in Toronto. Three student groups were also sanctioned for a joint statement claiming the October 7th atrocities were “an act of Palestinian resistance against ‘so-called Israel’” (Hager & Fine, 2023).

The University of Toronto has been applauded for its commitment to ensuring that student groups do not act in violation of university policy (B’nai Brith Canada, 2022). Following a protracted review, the University’s Graduate Student Union (UTGSU) was found to have acted inappropriately, restricting – on the basis of belief – who could join its Boycott, Divestment, & Sanctions (BDS) caucus, while continuing to impose fees on all UTGSU members. Provost Cheryl Regehr announced she would be withholding funding from the society (UofT News, 2022).

The BDS, also mentioned during the US Congressional hearing, is a well-funded global coalition, founded in 2005 and “endorsed by over 170 Palestinian political parties, organizations, trade unions and movements” (Canadian BDS Coalition, n.d.). There are many Canadian student unions and associations listed on the BDS member site, representing well over a million Canadian students (BDS HUB, n.d.).

Given that tensions are likely to further escalate, it is essential that all Canadian institutions are clear that while they are supportive of freedom of expression, that hate speech has no place on Canadian university campuses, and that all students and staff have the right to study and work in an environment free of threat and harassment.

It is unclear to what extent, if any, these recent incidents may be impacting Canadian’s perception of higher learning. Canadian universities and colleges have traditionally enjoyed the confidence of the public. In fact, according to a Nanos (2023) poll, they are perceived as the most valuable social institution in the country, with a mean score of 7.3 out of 10, albeit down from 7.9 in 2021.

That does not mean, however, that Canadians are fully satisfied with the country’s higher education system, particularly with respect to what is being taught. A recent Leger (2023) survey found that:

- “Canadians believe that universities and colleges need to teach more practical and career-focused skills (83%)”.

- “[T]hree-quarters of Canadians (73%) believe practical work experience is becoming more important than education.”

- Problem solving, adaptability, and digital literacy “are the top skills Canadians believe will become more important in the future”.

- “Judgement/decision making, people skills, and resiliency are also viewed as abilities/skills that will become more important”.

- “Canadians say 42% of post-secondary education should be provided by industry (e.g., businesses, professionals, associations), while 58% should be provided by educational institutions.”

It is within this complex, ever-changing, and increasingly polarized context, that academic integrity needs to be better understood and strengthened. I now turn to definitions of academic integrity and frameworks that are aligned with this essential pursuit.

What is Academic Integrity and Why is it Essential?

The term academic integrity began to receive focused attention in North America in the late 1990s, supported in large measure by the International Center for Academic Integrity (ICAI), co-founded by the “father of research on academic integrity” the late Don McCabe (McCabe, 2016). Don had been conducting surveys on student academic misconduct across the US, since the early 1990s. I reached out to Don in the early 2000’s, and together we conducted the first multi-institutional survey on academic misconduct by higher education students in Canada (see Christensen Hughes & McCabe, 2006a, 2006b).

I also began to attend ICAI conferences and was particularly inspired at one by keynote speaker Thomas Lickona, author of Educating for Character: How our Schools can Teach Respect and Responsibility (1991). Lickona made the case for explicitly (re)introducing values to education at all levels. Lickona argued there had been a dramatic decline in ethical behaviour in American society including amongst the young. He argued that democracy depended on a shared sense of morality. Citing Theodore Roosevelt, Lickona offered, “To educate a person in mind and not in morals is to educate a menace to society” (p. 3).

The ICAI’s stated mission was to “promote academic integrity and ethics in schools and in society at large” (ICAI, 2021, p.3). Don McCabe and the other founders recognized that integrity was essential to the work of the academy – “teaching, learning, research and service” – yet “scholarly institutions rarely identify and describe their commitment to the principles of integrity in positive and practical terms (p. 4). The ICAI defined academic integrity as “A commitment, even in the face of adversity, to five fundamental values: honesty, trust, fairness, respect and responsibility” (ICAI, 2021, p. 4). In 2014, a sixth value, courage, was added.

Similar to the ICAI’s definition are the Seven Sacred Teachings or Seven Grandfathers, fundamental to several Indigenous peoples in Canada. These teachings provide “a foundation for personal responsibility…demonstrate[ing] the interconnectedness of one’s actions with the lived environment…” (Maracle, 2020 , para. 2). The seven values include: respect, bravery, honesty, wisdom, humility, truth, and love. Over the past several years, and in keeping with Canada’s commitment to Truth and Reconciliation, educational resources built off these values have been developed, both as a framework for understanding academic integrity (Maracle, 2020) and for living a moral life (Bouchard et al., 2023). Today, both the ICAI’s values and the Seven Sacred Teachings can be found on the websites of schools, universities and colleges across Canada.

I have long argued that integrity is absolutely essential to the work of the academy and its continued, privileged position of trust in society (Eaton & Christensen Hughes, 2022, p. xiii):

Academic integrity…is—and must be—at the core of our purpose, practice and the products of scholarly work. The degrees we confer (and the knowledge, skills and values they are supposed to represent) and the truths we disseminate (through research with integrity), must be beyond reproach.

Given recent events, I would add that ensuring freedom of expression, alongside the emotional and physical safety of our students, faculty and staff, are essential additional dimensions. Yet criticism of the academy’s commitment to these ideals appears to be growing. If administrators and faculty are not bringing the highest levels of integrity to their own roles – consistently exhibiting a strong moral compass – it is hard to imagine that students would.

Frameworks of Integrity for Faculty and Administrators

The implications of a full commitment to academic integrity are far-reaching, particularly for faculty and administrators. This includes upholding the central tenet of academic freedom. Universities Canada’s (2011) acknowledges academic freedom is “fundamental to the mandate of universities to pursue truth, educate students and disseminate knowledge and understanding”, and also that “academic freedom must be based on institutional integrity, rigorous standards for enquiry and institutional autonomy…”.

Dea (2019) articulates the implications of academic freedom for the role of tenured faculty:

[C]onducting scholarship honestly, ethically, and according to the standards of your discipline or subdiscipline. That means performing your assigned teaching duties, grading student work fairly, subjecting one’s work to peer review, reporting research results honestly, properly crediting other scholars’ contributions, being careful not to misrepresent one’s own expertise or position (for instance, being clear that one’s extramural expression does not represent one’s university), and so on.

While Dea’s focus on honesty and ethics in scholarly work is welcome, her treatment of teaching is arguably more narrowly focused, reflecting quite traditional – and insufficient – expectations.

Over twenty years earlier, a much more extensive list of Ethical Principles and Professionalism in University Teaching (Society for Teaching and Learning in Higher Education, 1996) was developed, as “a set of basic ethical principles that define the professional responsibilities of university professors in their role as teacher” (p. 1). These principles included:

Principle 1: Content Competence (“course content is current, accurate, representative, and appropriate…consistent with stated course objectives”) (p. 1);

Principle 2: Pedagogical Competence (“selects methods of instruction, that according to research evidence…are effective in helping students to achieve the course objectives…[and, for mastery based assignments] provides students with adequate opportunity to practice and receive feedback”) (p. 2);

Principle 3: Sensitive Topics (deals with potentially sensitive topics “in an open, honest, and positive way”) (p. 2);

Principle 4: Student Development (“instruction that facilitates learning and encourages autonomy and independent thinking…[treating] students with respect and dignity) (p. 2-3);

Principle 5: Dual Relationships with Students (“does not enter into dual-relationships with students…[and avoids] actual or perceived favouritism”) ( p. 3);

Principle 6: Confidentiality (“student grades, attendance records, and private communications are regarded as confidential materials, and are released only with student consent, or for legitimate academic activities”) (p. 3);

Principle 7: Respect for Colleagues (“respects the dignity of her or his colleagues and works cooperatively with colleagues”) (p. 4)

Principle 8: Valid Assessment of Students (“assessment of students is valid, open, fair, and congruent with course objectives”; is aware of research “on the advantages and disadvantages of alternative methods of assessment…the teacher selects assessment techniques…as reliable and valid as possible” and “by means appropriate for the size of the class, students are provided with prompt and accurate feedback on their performance at regular intervals throughout the course…an explanation as to how their work was graded, and constructive suggestions as to how to improve“) (p. 4);

Principle 9: Respect for Institution (“a university teacher is aware of and respects the educational goals, policies and standards of the institution in which he or she teaches” (p. 5).

These principles have been adopted by several Canadian universities, and in fact have been taught as part of faculty development activities (see for example, Ethical Principles and Professionalism in University Teaching, n.d., Queen’s University). In my experience, however, they are worthy of much more attention than they have received. Given the pressures for change previously reviewed, these principles may be more relevant now than they have ever been.

Ethical principles have also been articulated for university leaders. In the US, one example is provided by the American Association of University Administrators (AAUA, 2017). An abbreviated version follows:

- “We commit to the highest level of integrity. Honest behavior is the key to establishing trust among those with whom we work…”

- “We uphold the values of fairness and equity. We welcome and encourage diverse perspectives and respect the dignity of all individuals…”

- “We strive for accuracy and transparency. Information is the lifeblood of our profession…”

- “We respect confidentiality and protect the privacy of information…”

- “We support the missions of our institutions… In all situations we demonstrate professional judgment and respond in ways that meet the highest standards of our profession.”

- “We actively seek support when concerned about an ethical issue…”

- “We raise our voices when the ethical standards of our profession are not being upheld…We act with moral courage, even in the face of risk, danger, or fear.”

- “We pursue professional opportunities to acquire new ethical knowledge and practices…to increase our awareness and knowledge of ethical best practices and emerging ethical issues.”

- “We actively promote and disseminate these Principles. We have a responsibility to promote ethical conduct within our profession…”

While I could not find any similar overarching statement of a commitment to integrity by Canadian university leaders, multiple commitments have been made towards advancing specific initiatives that arguably have principles of integrity at their core. For example:

Universities Canada’s commitments to Truth and Reconciliation (Universities Canada, 2023):

Universities commit to advancing truth as a step toward reconciliation. This includes acknowledging their role in colonialism and the legacy of residential schools in education in Canada…Universities commit to developing opportunities for Indigenous students, faculty, researchers, staff and leaders at every level of the institution through governance structures, policies, and strategies that respect and make space for Indigenous expertise, Knowledges and cultures.

Universities Canada’s commitment towards the Scarborough Charter (Universities Canada, 2021a):

a commitment to take concrete, meaningful action to address anti-Black racism and promote Black inclusion in Canadian higher education…Universities Canada members are committed to advancing equity, diversity and inclusion and addressing all forms of systemic racism on our campuses and in our communities.

Canada’s universities’ commitments to Canadians (Universities Canada, 2021b):

We prepare all students with the knowledge and competencies they need to succeed in work and life, empowering them to contribute to Canada’s social, economic, and cultural vitality…Universities commit to improving accessibility to higher education for all Canadians…We deliver enriched learning experiences that meet the ever-changing needs of students, the workforce, communities and broader society…Canada’s universities pursue and support more ground-breaking research than any other economic sector, for the benefit of Canada and the world.

The U15 Group of Canadian Research Universities (2023) has also developed Safeguarding Research in Canada: A Guide for University Policies, in response to concerns “that some foreign entities are seeking to exploit and misuse the very openness and inclusivity that drives our success and world-class performance” (p. 1). They articulate the following values for “safeguarding research at Canadian institutions” (p. 2):

- Integrity: as a core principle for researchers and institutions

- Respect: for academic freedom, open-science and diverse and inclusive campus environments

- Trust: across funders, partners, governments, and universities

- Resilience: in developing policies and practices to safeguard research and advance research activity

- Compliance: with all relevant laws, regulations, and ethical standards related to research security.

In summary, there are many frameworks that underscore the essentiality of integrity to the work of the academy, including faculty and administrators, with numerous commitments having been made. The ones reviewed here relate to academic freedom, integrity in scholarship, ethical teaching practice, transparent leadership, Truth and Reconciliation, anti-Black racism, accessibility, and the relevance of what students are required to learn. Higher education in Canada is highly regulated, with many checks and balances aligned with these expectations, including institutional codes of conduct amongst other policies and regulations.

Given all the disruptions occurring in the broader context, however, and important questions being raised, any accomplishments or progress to date towards these types of frameworks and commitments should not be taken for granted. What is missing, is a comprehensive assessment of our success in living up to these ideals, with input from those we are intended to serve. Research that does exist has tended to focus on academic misconduct by students. And that research suggests that while most students may be approaching their work with integrity, there is growing reason for concern.

The Growing Prevalence of Student Academic Misconduct

Academic misconduct is generally defined as “anything that gives a student an unearned advantage over another” (Mullens, 2000, p. 23). In 2006, Don McCabe and I published two papers in the Canadian Journal of Higher Education (Christensen Hughes & McCabe, 2006a, 2006b) on the topic. The first was a literature review demonstrating the growing prevalence of student academic misconduct in the US, as well as an exploration of its causes. Based on this review, we provided recommendations for minimizing its prevalence, including (Christensen Hughes & McCabe, 2006a, p. 49):

- Revisiting the goals and values of higher education

- Recommitting to quality in teaching and assessment practice

- Establishing effective policies and invigilation practices

- Providing educational opportunities and support for all members of the university community

- Using (modified) academic honour codes

Our second paper reported the results of the first multi-institution Canadian study, carried out between 2002 and 2003. Over 16,000 students (undergraduate and graduate) completed surveys, providing self-reported data about their views and participation in 25 questionable behaviours (Christensen Hughes & McCabe, 2006b). Several thousand Faculty and TAs were also surveyed on their perceptions and behaviours.

The top three behaviours students reported participating in, at least once in the past year, for written assignments, were (Christensen Hughes & McCabe, 2006b, p. 13):

- Sharing an assignment with another student so they have an example to work from (66% undergrads, 52% grads)

- Working on an assignment with others when the instructor asked for individual work (45% undergrads, 29% grads)

- Copying a few sentences of material from a written source without footnoting them in the paper (37% undergrads, 24% grads)

For tests and examinations, the highest rates were (Christensen Hughes & McCabe, 2006b, p. 13):

- Getting questions and answers from someone who has already taken the test (38% undergrads, 16% grads)

- Helping someone else cheat on a test (8% undergrads, 4% grads)

- Copying from another student during a test with his or her knowledge (6% undergrads, 3% grads)

Most respondents (students, faculty and TAs) viewed the most common of these behaviours (i.e., “sharing an assignment with another student so they have an example to work from”) as “not cheating” or “trivial cheating” (Christensen Hughes & McCabe, 2006b, p. 9). Most students (but not the majority of faculty or TAs) also considered “working on an assignment with others when the instructor asked for individual work” and “receiving unpermitted help on an assignment” as not cheating or trivial cheating. And, most undergraduate students (not graduate students, faculty or TAs) considered “getting questions and answers from someone who has already taken the test” as “not cheating” or “trivial cheating”.

Behaviours reported by fewer students, but arguably concerning to the integrity of the academy included (Christensen Hughes & McCabe, 2006b, p. 13):

- Fabricating or falsifying lab data (25% undergrads, 6% grads)

- Fabricating or falsifying a bibliography (17% undergrads, 9% grads)

- Turning in work done by someone else (9% undergrads, 4% grads)

Amongst the lowest reported self-reported behaviours were:

- Turning in a paper obtained in large part from a term paper “mill”/web site that did not charge (2% undergrads, 1% grads)

- Damaging library or course materials (2% undergrads, 2% grads)

- Turning in a paper obtained in large part from a term paper “mill”/web site that did charge (1% undergrads, 0% grads)

In the thousands of open-ended responses, students justified their behaviours, reporting for example, that they learned more when they “collaborated” (Christensen Hughes & McCabe, 2006b, p. 15). They also criticized what they perceived as a lack of institutional commitment to following policies and practices that discourage cheating. As examples, students wrote (Christensen Hughes, 2017):

If there was more supervision and we felt we couldn’t we wouldn’t. We basically know there is a very good chance we will get away with it. (p. 44)

As much as it pains me to say, if you eliminate hats during exams, that would be the right step. (p. 44)

I find that even when people are caught cheating during a test or examination, they are often just told to stop. The measures that are supposed to be taken are not taken. I think this leads to the attitude some people take that cheating is not a big deal. (p. 49)

To be honest, I really don’t know the penalties of cheating, and maybe that’s why I have no problem looking at another student’s multiple-choice answers when I get a chance. (p. 52)

Students also challenged the type of assessments they were given, arguing that they did little to enhance their learning. As examples (Christensen Hughes, 2017):

As long as universities are not about learning, students will cheat…Are assignments given to teach the students the material, or are assignments given to determine what the student will get as a mark? There is only one primary purpose. ‘Cheating’ allows the student to get a better mark. (p. 55)

Students DO NOT COME TO SCHOOL TO LEARN…we come because a university education is deemed socially and economically necessary…We have been brain washed into a game, whereby we memorize vast amounts of material, regurgitate it onto paper in a crowded room, and then forget about it… (p. 56)

Many also complained about faculty being ‘lazy’, using multiple choice exams that tested for recall of trivial details (encouraging the use of ‘cheat sheets’), or not changing exams and assignments from one year to another. While 75% of faculty in our study reported that they regularly changed exams to discourage cheating, one in four indicated they did not (p. 14). We observed, “It is clear that when students perceive game playing conditions, such as when an old exam is available to a select few, that students are more likely to engage in game playing behaviour” (Christensen Hughes & McCabe, 2006b, p. 16).

Don and I concluded that large numbers of Canadian students reported engaging “in a variety of questionable behaviours in the completion of their academic work” (Christensen Hughes & McCabe, 2006b, p. 17) and that “consistent with the view of over 40% of faculty and TAs, cheating may be a serious problem in Canadian higher education” (p. 18).

Current Research on Student Academic Misconduct

Since the release of my work with Don McCabe, concern about student misconduct in Canadian universities has continued to grow, championed in large measure by Sarah Elaine Eaton from the University of Calgary. In Contract Cheating in Canada: A Comprehensive Overview (Eaton, 2022), Sarah provides a historical account of the multi-billion-dollar contract cheating industry (third-party providers of academic work), from the early “paper mills” or “walk-in” custom essay-writing services of the 1960s and 1970s, to today’s sophisticated online services. She makes the case that the prevalence of contract cheating in Canada is due in part to a compromised policy environment, in which such services are not considered illegal (Adlington & Eaton, 2021).

Students are regularly targeted with messages from these businesses, “via social media or direct email, assuring them that this is acceptable and common practice” (QAA, 2022, p. 8). Often listed under ‘tutoring’, ‘copy-editing’ or ‘exam help’, students who are struggling can be easily tempted. Those who avail themselves of inappropriate ‘support’ may not only find themselves facing the consequence of having violated institutional policies, but they can also be vulnerable to extortion and blackmail (Friesen, 2023). I have personally received email from academic service suppliers, attempting to report students for cheating, ironically because they hadn’t paid their bill.

While the prevalence of contracting cheating is hard to determine, Newton (2018) reviewed over 50,000 students’ responses across 65 studies and multiple years, finding that “contract cheating was self-reported by a historic average of 3.52% of students” (p. 1). Studies undertaken from 2014 onwards, however, found a much higher rate of 15.7%, suggesting that contract cheating is significantly on the rise. These most recent results are in stark contrast to my earlier study, which found only 1% of students admitting to having bought academic work from a paper mill or website, just over a decade ago.

As student academic misconduct has become more technologically enabled (either through Contract Cheating and/or ChatGPT) its deterrence has become more important than ever.

Some Steps Forward

Today’s challenging higher education environment suggests that all institutions need to be reflecting meaningfully on their purpose and their values, including their commitment to integrity – broadly defined. Placing students and their learning at the centre of this commitment, is an essential step. As does the creation and dissemination of new knowledge. Policies and practices need to be assessed for their alignment. Frameworks (such as those reviewed earlier in this chapter) can serve as useful guides. Plans (and investments) for ensuring faculty and staff have the skills and capacity to meet stated commitments should follow.

At Yorkville University, over the past year we have clarified our strategic priorities, including areas of distinctive capability, such as the provision of transformative learning experiences, defined in part by a commitment to enhancing self-efficacy, being treated and treating others with respect and dignity, and developing an ethic of care. The student experience is another area of priority, ensuring both domestic (largely online learners) and campus-based international students experience “relentless welcome” (David Scobey, in Felten & Lambert, 2020, p. 14) as a defining attribute.

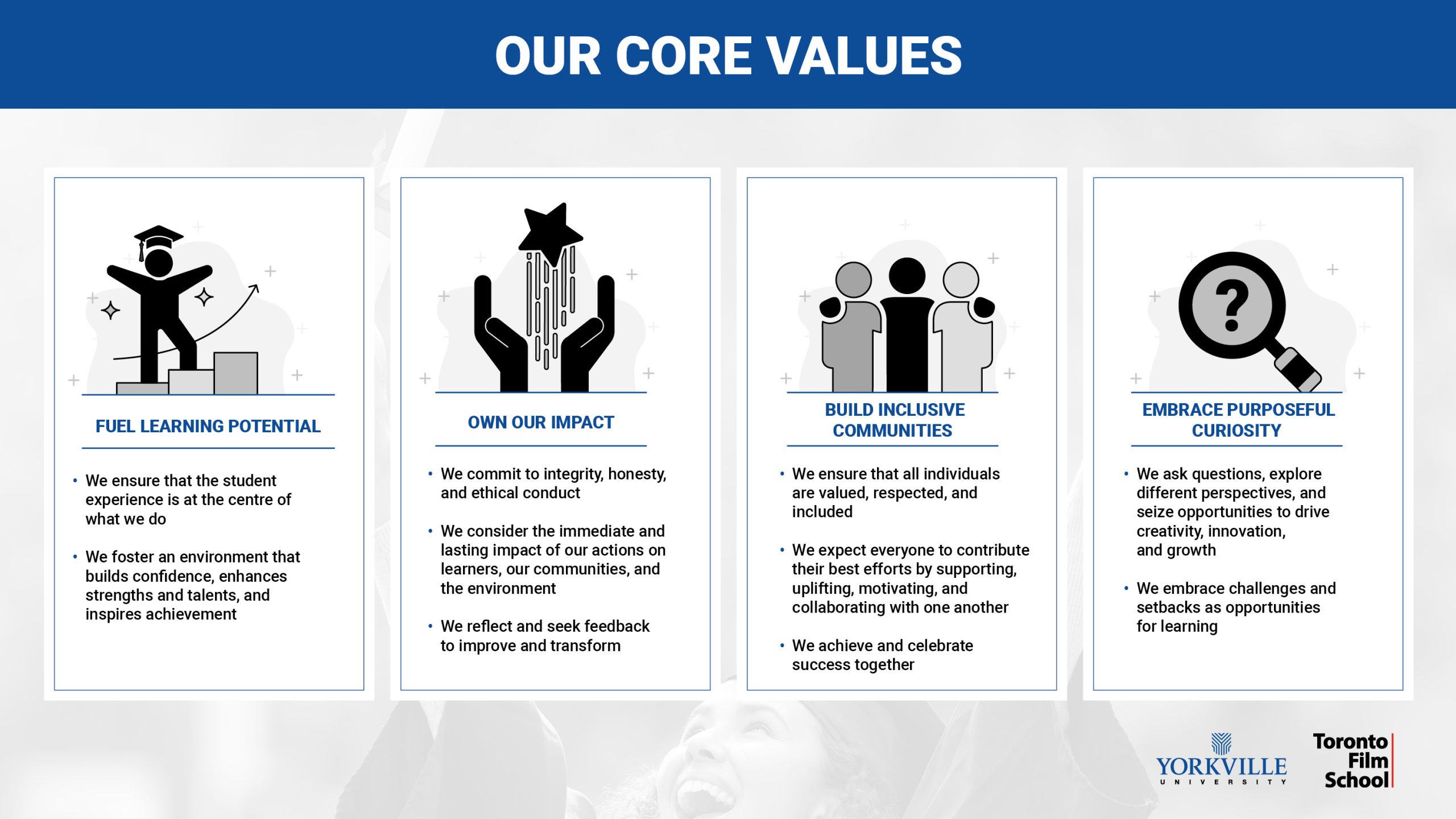

We have also undertaken an annual survey of all our employees, to assess how they are experiencing our culture, and to identify opportunities for improvement. Last year’s (2022) results suggested we had work to do in clarifying our values. Following a highly participative process, Yorkville’s core values were officially released through a number of town halls in the fall of 2023, in which employees assessed our current strengths as well as institutional and personal barriers to living them more fully. We are now engaged in a process of addressing the identified barriers (Yorkville University, 2023).

Each of these values has quickly become core to our identity and priorities. We are currently reviewing and updating policies, ensuring their alignment, such as our Code of Conduct.

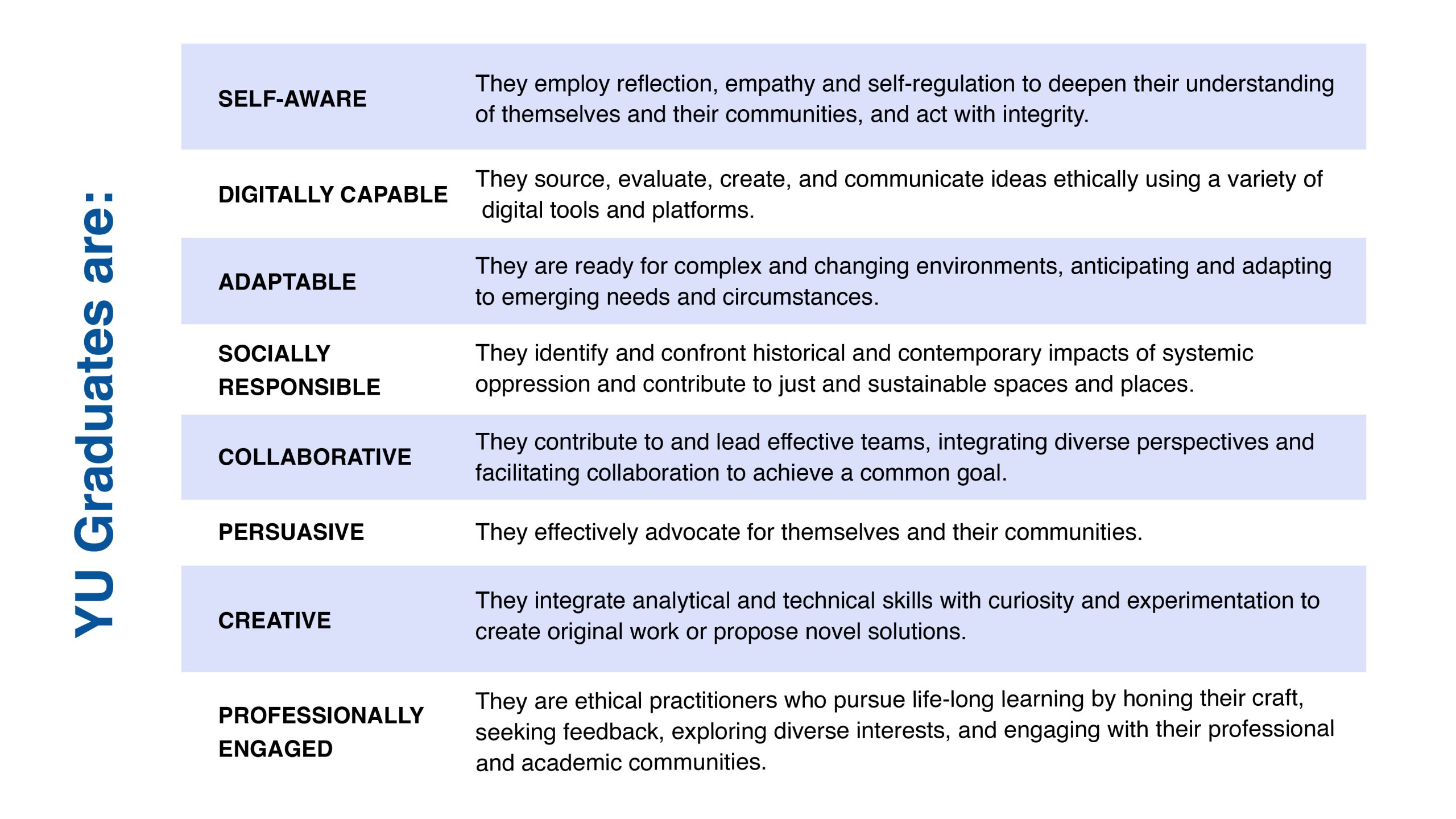

Another important undertaking has been a commitment to ensuring that our students are well prepared for their career aspirations, as well as changing societal needs and workplace expectations. Yorkville’s signature learning outcomes (SLO’s), updated in 2023, reflect our commitment to teaching students practical, transferable skills and values.

We are now in the process of developing a signature pedagogical commitment, that will capitalize on our uniquely small classes (approximately 20-35 students) as well as the effective design of highly accessible and interactive online and physical spaces. Significant revision of our approach to student assessment will follow. These commitments will be supported by the development of a required, training and development program for faculty, in which the Ethical Principles in University Teaching (1996) will figure prominently.

We have also recently revised our academic integrity policies, to account for Generative AI, including ChatGPT. In keeping with our SLO’s, our guiding philosophy is that students need to be taught how to effectively and ethically apply Generative AI to their academic work, as well as their lives in general.

While we still have much work to do, the steps we have taken are already having an impact.

Conclusion

We are living through incredibly turbulent times in higher education, where the ideals of integrity are being increasingly challenged. These times call for clear, ethical leadership, in multiple domains. Of particular importance to the theme of this chapter, is the essentiality of a renewed commitment to integrity, on the part of faculty and administrators, to students and their learning. This means the reconsideration of learning outcomes, ensuring the inclusion of transferable skills, appropriate and engaging pedagogies, formative assessments, support for accessibility (including online learning) and a context that is both challenging and supportive, free of hate speech and any kind of physical threat.

As Don McCabe and the other founders of the ICAI observed, “scholarly institutions rarely identify and describe their commitment to the principles of integrity in positive and practical terms (ICAI, 2021, p. 4 ). The time to do so is now.

References

American Association of University Administrators. (2017). Ethical principles for college and university administrators. https://aaua.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/11/Ethical-Principles.pdf.

Ackman, B [@BillAckman]. (2023). The presidents of @Harvard, @MIT, and @Penn were all asked the following question under oath at today’s congressional [Video attached] [Tweet]. X. https://twitter.com/BillAckman/status/1732179418787783089

Adlington, A., & Eaton, S. E. (2021). Contract cheating in Canada: Exploring legislative options. Calgary, Canada: University of Calgary. http://hdl.handle.net/1880/114088

Asmelash, L. (2023). DEI programs in universities are being cut across the country. What does this mean for higher education? CNN. https://www.cnn.com/2023/06/14/us/colleges-diversity-equity-inclusion-higher-education-cec/index.html

BDS HUB (n.d.). Who Supports BDS in Canada. https://www.cjpme.org/who_supports_bds#students

Berdhal, L., & Bens, S. (2023, June 26). Academic integrity in the age of ChatGPT. University Affairs. https://www.universityaffairs.ca/career-advice/the-skills-agenda/academic-integrity-in-the-age-of-chatgpt/

B’nai Brith Canada (2022). McGill President Promises “Action” over Illegitimate Anti-Israel Referendum. https://www.bnaibrith.ca/mcgill-president-promises-action-over-illegitimate-anti-israel-referendum/

Borter, G. (2023, December 7). US House committee opens probe into Harvard, Penn, MIT after antisemitism hearing. Reuters. https://www.reuters.com/world/us/us-house-committee-opens-investigation-into-harvard-penn-mit-after-antisemitism-2023-12-07/

Bouchard, D., Martin, J., & Cameron K. (2023). Seven Sacred Teachings: Niizhwaaswi gagiikwewin. Werklund School of Education, University of Calgary. https://werklund.ucalgary.ca/teaching-learning/seven-sacred-teachings-niizhwaaswi-gagiikwewin

Brenan, M. (2023). Americans’ confidence in highereEducation down sharply. Gallup. https://news.gallup.com/poll/508352/americans-confidence-higher-education-down-sharply.aspx.

Calcutt, A. (2016, November 18). The surprising origins of ‘post-truth’ – and how it was spawned by the liberal left. The Conversation. https://theconversation.com/the-surprising-origins-of-post-truth-and-how-it-was-spawned-by-the-liberal-left-68929

Canadian BDS Coalition (n.d.). About BDS. https://bdscoalition.ca/about-bds/.

Canadian Press. (2023). Federal government hikes income requirement for foreign students, targets ‘puppy mill’ schools. CBC News. https://www.cbc.ca/news/politics/liberals-double-income-requirement-foreign-students-1.7052387

CBC News. (2023, November 3). UBC among 4 Canadian universities facing class-action lawsuits for alleged antisemitic incidents. CBC. https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/british-columbia/ubc-among-4-canadian-universities-facing-class-action-lawsuits-for-alleged-antisemitic-incidents-1.7018309.

Center for Antisemitism Research. (2023). Campus antisemitism: A study of campus climate before and after the Hamas terrorist attacks. https://www.adl.org/resources/report/campus-antisemitism-study-campus-climate-and-after-hamas-terrorist-attacks.

Christensen Hughes, J. (2024, in press). ‘Bringing Caring, Community and Confrontation into the Academy: Embracing an Ethic of Care’, In M. Drinkwater & Y. Waghid (Eds.) The Bloomsbury Handbook of Ethics of Care in Transformative Leadership in Higher Education, [NB page number to be added at proof]. London: Bloomsbury Academic.

Christensen Hughes J. (2023). Rethinking higher education in the world of AI. Special to Toronto Sun. https://torontosun.com/opinion/columnists/opinion-rethinking-higher-education-in-the-world-of-ai%E2%80%AF%E2%80%AF.

Christensen Hughes, J. (2017). Understanding academic misconduct: Creating robust cultures of integrity. Paper presented at the University of Calgary, Calgary, AB. https://prism.ucalgary.ca/items/53ed0fb4-89e8-4c28-b633-8199f34e175b

Christensen Hughes, J., & Eaton, S. E. (2022). Academic misconduct in Canadian higher education: Beyond student cheating. In S. E. Eaton & J. Christensen Hughes (Eds.), Academic integrity in Canada: An enduring and essential challenge. Springer.

Christensen Hughes, J. M., & McCabe, D. L. (2006a). Understanding academic misconduct. Canadian Journal of Higher Education, 36(1), 49-63. Retrieved from https://journals.sfu.ca/cjhe/index.php/cjhe/article/view/183525.

Christensen Hughes, J. M., & McCabe, D. L. (2006b). Academic misconduct within higher education in Canada. The Canadian Journal of Higher Education, 36(2), 1–21. http://journals.sfu.ca/cjhe/index.php/cjhe/article/view/183537/183482.

Coghlan, S., Miller, T., & Paterson, J. (2021). Good proctor or “Big Brother”? Ethics of online exam supervision technologies. Philosophy & Technology, 34(4), 1581–1606. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13347-021-00476-1

COU (2023). Ontario’s universities demonstrate longstanding commitment to enhancing efficiency and call on government to urgently implement panel’s recommendations. Ontario Universities. https://ontariosuniversities.ca/news/ontarios-universities-commitment-to-enhancing-efficiency/

C-SPAN2-1. (2023). University Presidents Testify on College Campus Antisemitism, Part 1 [Video]. https://www.c-span.org/video/?532147-1/university-presidents-testify-college-campus-antisemitism-part-1

C-SPAN2-2. (2023). University Presidents Testify on College Campus Antisemitism, Part 2 [Video]. https://www.c-span.org/video/?532147-101/university-presidents-testify-college-campus-antisemitism-part-2

C-SPAN2-3. (2023). University Presidents Testify on College Campus Antisemitism, Part 3 [Video]. https://www.c-span.org/video/?c5096235/user-clip-presidents-mit-upenn-harvard-refuse-denounce-calls-genocide-jews

D’Agostino S. (2023). In class, some colleges overlook technology’s dark side. Inside Higher Ed. https://www.insidehighered.com/news/tech-innovation/teaching-learning/2023/11/16/some-colleges-overlook-technologys-dark-side.

Dea, S. (2019, January 18). The price of academic freedom. University Affairs. https://www.universityaffairs.ca/opinion/dispatches-academic-freedom/the-price-of-academic-freedom/.

Eaton, S. E. & Christensen Hughes, J. (2022). Academic integrity in Canada: An enduring and essential challenge. Springer. https://link.springer.com/book/10.1007/978-3-030-83255-1.

Eaton, S. E. (2022). Contract cheating in Canada: A comprehensive overview. In S. E. Eaton & J. Christensen Hughes (Eds.), Academic integrity in Canada: An enduring and essential challenge. Springer.

Ethical Principles and Professionalism in University Teaching (n.d.). Queen’s University. https://onq.queensu.ca/shared/TLHEM/ethics/index.html

Evans, M. (2023). Update on Queen’s operating budget deficit. Queen’s University. https://www.queensu.ca/provost/sites/provwww/files/uploaded_files/Budget/Update%20on%20Queen’s%20Operating%20Budget%20Deficit%2C%20Provost%20Email%20November%2030%2C%202023.pdf

Felten, P., & Lambert, L. M. (2020). Relationship-rich education: How human connections drive success in college. Johns Hopkins University Press.

Friesen, J. (2023). Hired exam-takers, blackmail and the rise of contract cheating at Canadian universities. Globe and Mail. https://www.theglobeandmail.com/canada/article-university-students-cheating-exams/.

Greenawalt, K. (1992). Free speech in the United States and Canada. Law and Contemporary Problems, 55(1), 5–33. https://doi.org/10.2307/1191755

Hager M. & Fine S. (2023). York University suspends at least three employees after charges in Indigo store vandalism. Globe and Mail. https://www.theglobeandmail.com/canada/article-york-university-suspends-at-least-three-employees-after-charges-in/.

Haidt, J. (2016). Why universities must choose one telos: Truth or social justice. The Heterodox Academy. https://heterodoxacademy.org/blog/one-telos-truth-or-social-justice-2/.

Hoffman, A. J. (2016). Why academics are losing relevance in society – and how to stop it. The Conversation. https://theconversation.com/why-academics-are-losing-relevance-in-society-and-how-to-stop-it-64579.

ICAI. (2021). The fundamental values of academic integrity (3rd ed.). https://academicintegrity.org/about/values.

Irhouma, T., & Johnson N. (2022). Digital learning in Canada in 2022: A changing landscape. Canadian Digital Learning Research Association. http://www.cdlra-acrfl.ca/wp-content/uploads/2023/01/2022_national_report_en.pdf

Lederman, D. (2023). Majority of Americans lack confidence in value of 4-year degree. Inside Higher Ed. https://www.insidehighered.com/news/2023/04/03/majority-americans-lack-confidence-value-four-year-degree.

Leger (2023). Canadians’ attitudes towards the future of education and how they want to learn (5th ed). Education, Tech and Innovation Series. https://leger360.com/surveys/the-future-of-education-in-canada/#gform_wrapper_58.

Liester, Mitchell. (2022). The suppression of dissent during the COVID-19 pandemic. Social Epistemology Review and Reply Collective 11(4), 53-76. https://wp.me/p1Bfg0-6Jw.11. 53-76.

Lickona, T. (1991). Educating for Character: How Our Schools Can Teach Respect and Responsibility. New York: Bantam Books, 1991.

Penn [@Penn]. (2023, December 6). A video message from President Liz Magill [Video Attached] [Post]. X. https://twitter.com/i/status/1732549608230862999

Maracle, I. B. J. (2020). Seven grandfathers in academic integrity. University of Toronto Student Life. https://studentlife.utoronto.ca/wp-content/uploads/Seven_Grandfathers_in_Academic_Integrity.pdf

Matusz, P. J., Abalkina, A., & Bishop, D. V. M. (2023, November 30). The threat of paper mills to social science journals: The case of the Tanu.pro paper mill. Mind, Brain & Education. https://doi.org/10.31234/osf.io/64j8h.

McCabe, D. (2016). Donald McCabe: Obituary. The Star Ledger. https://obits.nj.com/us/obituaries/starledger/name/donald-mccabe-obituary?id=16784478

Moon, R. (2008). Hate speech regulations in Canada. Florida State University Law Review, 36(1), Article 5. https://ir.law.fsu.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1132&context=lr

Mullens, A. (2000, December). Cheating to win. University Affairs, 41(10), 22–28.

Nanos (2023). Satisfaction with Canada as a country continues to decline – Universities and health system seen as top contributors to Canada being a better country, political institutions rated lowest. https://nanos.co/satisfaction-with-canada-as-a-country-continues-to-decline-universities-and-healthcare-seen-as-top-contributors-to-canada-being-a-better-country-political-institutions-rated-lowest-nanos/.

Nature. (2023). Rich countries must align science funding with the SDGs. Nature, 621(7979), 444–444. https://doi.org/10.1038/d41586-023-02847-4

Newton, P.M. (2018). How common is commercial contract cheating in higher education and is it increasing? A systematic review. Frontiers in Education, 3(67). https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/feduc.2018.00067/full.

OpenAI (2023). GPTs are GPTs: An early look at the labor market impact potential of large language models. https://openai.com/research/gpts-are-gpts.

QAA. (2022). Contracting to cheat: How to address contract cheating, the use of third-party services and essay mills. https://www.qaa.ac.uk/docs/qaa/quality-code/contracting-to-cheat-in-higher-education.pdf?sfvrsn=f66af681_8.

Retraction Watch. (n.d.a). The Retraction Watch Database. http://retractiondatabase.org/RetractionSearch.aspx

Retraction Watch. (n.d.b). Retracted coronavirus (COVID-19) papers. https://retractionwatch.com/retracted-coronavirus-covid-19-papers/

Stevens, S. (2023). Harvard gets worst score ever in FIRE’s college free speech rankings. Fire. https://www.thefire.org/news/harvard-gets-worst-score-ever-fires-college-free-speech-rankings

Society for Teaching and Learning in Higher Education. (1996). Ethical principles in university teaching. University of Alberta. https://www.ualberta.ca/graduate-studies/media-library/professional-development/gtl-program/gtl-week-january-2019/20190109-sthle-ethical-principles-in-teaching-handout.pdf

The Canadian Press. (2023, November 9). Quebec court orders pause to ratification of McGill student union pro-Palestine vote. City News. https://montreal.citynews.ca/2023/11/22/quebec-court-mcgill-palestine-vote/

U15 Group of Canadian Research Universities. (2023). Safe safeguarding research in Canada: A guide for university policies. https://u15.ca/wp-content/uploads/2023/06/2023-06-22.-U15-Leading-Practices-Safeguarding-Research-FINAL-3.pdf.

Universities Canada. (2011, October 25). Statement on academic freedom. https://www.univcan.ca/media-room/media-releases/statement-on-academic-freedom/

Universities Canada. (2021a, November 18). Scarborough Charter on anti-Black racism and Black inclusion. https://www.univcan.ca/media-room/media-releases/scarborough-charter-on-anti-black-racism-and-black-inclusion/

Universities Canada (2021b, November 11). Canada’s universities’ commitments to Canadians. https://www.univcan.ca/media-room/publications/canadas-universities-commitments-to-canadians/

Universities Canada. (2023, April 25). Universities Canada’s commitments to Truth and Reconciliation. https://www.univcan.ca/media-room/publications/universities-canadas-commitments-to-truth-and-reconciliation/

UofT News. (2022). U of T provost withholds fees from Graduate Students’ Union after it fails to act on student panel ruling. University of Toronto. https://www.utoronto.ca/news/u-t-s-provost-withholds-fees-graduate-students-union-after-it-fails-act-student-panel-ruling

Van Noordden, R. (2023). More than 10,000 research papers were retracted in 2023 — a new record. Nature, 624, 479-481, https://doi.org/10.1038/d41586-023-03974-8

Walker J. (2023, December 11). Harvard alumni outraged after president accused of plagiarizing dissertation. ABC News. https://wpde.com/news/nation-world/harvard-alumni-outraged-after-president-accused-of-plagiarizing-dissertation-christopher-rufo-and-christopher-brunet-claudine-gay-ivy-league-congress-stefanik-testimony-trending-college-university

Wright Dziech, B. (2023, September 20). Higher ed, we have a problem. Times Higher Ed. https://www.insidehighered.com/opinion/views/2023/09/20/higher-ed-cant-afford-its-left-wing-bias-problem-opinion

Yorkville University. (2023). About us. https://www.yorkvilleu.ca/about-us/

Zakaria, F. (2023). Fareed: US universities are pushing political agendas instead of excellence [Video]. CNN. https://www.cnn.com/videos/us/2023/12/10/fareeds-take-us-universities-education-gps-vpx.cnn

How to Cite

Christensen Hughes, J. (2024). The essentiality of academic integrity in an increasingly disrupted and polarized world. In M. E. Norris and S. M. Smith (Eds.), Leading the Way: Envisioning the Future of Higher Education. Kingston, ON: Queen’s University, eCampus Ontario. Licensed under CC BY 4.0. Retrieved from https://ecampusontario.pressbooks.pub/futureofhighereducation/chapter/the-essentiality-of-academic-integrity-in-an-increasingly-disrupted-and-polarized-world/