Steve Joordens and Irameet Kaur

Re-Imagining Education for an Uncertain Future: Can Technology Help Us Become More Human?

Steve Joordens and Irameet Kaur

Advanced Learning Technologies Lab

University of Toronto Scarborough

Introduction

Our current education system was built for a different time, and a different world. It was a world in which knowledge was important, and only a few were able to obtain deep knowledge related to some specific field of interest (Reigeluth & Garfinkle, 1994). Educators were among these people, and the primary task of educators was to procure, organize, and present this knowledge to students – giving them something that was very hard to acquire in any other way. If you were among those who understood engineering best, or law, or accounting, or aspired to become a doctor, you were positioned for success in life.

In the modern world knowledge remains relevant but is much more easily accessible than it once was. Thanks to online resources ranging from explainer videos on YouTube, to Wikipedia, to so-called Massive Open Online Courses, one can now learn from their choice of educator. That is, technology-assisted online learning has risen up as an alternative to the traditional lecture hall, and while one could argue that the quality of the learning might not be at the same level, the reality is that the quality of online learning varies widely, and some of the best online learning resources allow a quality of learning that is far superior to traditional approaches (Sun & Chen, 2016).

It is perhaps not surprising then, that as the ability to access high quality knowledge becomes progressively easy, success in life is determined more by the extent to which students can combine the knowledge they are learning with critical skills. These skills go by many names including the Six (or Seven) Cs (e.g., Nata & Tungsirivat, 2017), 21st Century Skills (e.g., Chalkiadaki, 2018), Soft Skills (e.g., Heckman & Kautz, 2012), Transversal Skills (e.g., Goggin et al., 2019), Transferable Skills (Assiter, 2017) or the term we will use here: The Skills of Success (Mitchell et al., 2010). While the specific skills associated with a given term vary slightly, all include critical and creative thought (aka, problem solving), socio-emotional communication and collaboration skills, and perhaps most important, the skill set involved in being able to negotiate the negative emotions that come with seeing the weaknesses in one’s current work, and being able to navigate those emotions to ultimately allow for personal growth (Lumpkin, 2020).

Over the last two to three decades, virtually every entity or organization that has considered the reforms to education that are needed to better align it with the Future of Work ultimately focuses on the challenge of how to include a serious and structured approach to skill development (Fullan, 2014; Joordens, 2018; Tam & Trzmiel, 2018). More specifically, how do we develop within our students the skills they need to be critical and creative, to be good listeners to others while also being able to represent themselves well, to be the kind of people who collaborate well with others to reach some common goal? Perhaps most importantly, can they also learn the core skills of personal growth, seeking out ways to improve despite the negative emotions this might cause, and then doing what needs to be done to improve the weakness? This is indeed a significant challenge. Teachers, and school administrators already feel overworked and undervalued (Naylor, 2001) and, as will be discussed below, developing skills takes significant time and effort. If we are to add a serious focus on skill development into our educational systems to better align it with the modern world, something we are currently spending time and effort on must go. That is, it is now critical that we free up the time to focus on skill development while not losing out on something valuable, for example the knowledge transmission that does remain relevant.

Why is it so critical to reform our educational systems in ways that focus more on the development of the core skills of success? In fact, these skills have always been important as evidenced by the fact that they tend to be the core skills that employers seek when hiring, yet also ones, they argue, that are generally not being developed well by our educational systems (Andrews & Higson, 2008). That said, the relevance of these skills has become even greater as more hands-on jobs are giving way to automation (Pouliakas, 2018) and as entrepreneurship opportunities have resulted in the creation of jobs that did not previously exist (Green & Henseke, 2016). Add to this the fact that only 27% of college graduates end up in a job directly related to their major (Able & Deitz, 2013), and the fact that those who are hired but are then found to lack these skills are often the first to be let go (Klaus, 2010). If we care about the future success of our students, we need to do a better job developing their skills of success.

Adding the Acceleration of AI to the Story

ChatGPT was released on November 30, 2022 (ZD Net, 2023) and has now become the focus of daily conversation, if not several daily conversations. The more we all come to understand the step forward in AI that it represents, the more we understand that AI will indeed change our world in ways we can’t totally predict and it will do so quickly. Almost nothing in our world will be immune to the impact of AI. According to a 2023 McKinsey report for example, roughly 15% of current jobs will be replaced by AI by the year 2030, with up to 30% eventually being replaced (Chui, 2023). Other pundits have estimated the lost jobs number as closer to 40% of jobs replaced with AI in as little as 5 years. Nobody is certain of course as we are still amazed on an almost daily basis by just how much current variants of AI can do, and those variants are improving quickly and will continue to do so.

The acceleration of AI raises a critical question connected to the first section of this chapter; what jobs will be left for humans to do? Once again, we cannot be 100% sure, but our best bet is that it will be the kinds of jobs that leverage our humanity, the kind of jobs that lean very heavily on exactly the skills highlighted above; critical and creative thought, clear effective communication and collaboration, and the skills of personal growth. Thus, the acceleration of AI has not changed the general vision of where our approach to education must go, but it has made the need greater than ever, and the timeframe within which to meet this need is shorter than we would have ever imagined.

As authors asked to speculate about the future of education, and the role educational technologies will play, it is tempting to try to predict all the ways AI will impact what we do and how we do it. We will do a little of that in this chapter, but our primary focus will be a little different. Specifically, the question guiding our thinking is this:

If our approach to education is to change in a way that will better prepare our students for an uncertain future, what would that education system look like, and what role might technologies – including AI – play within it?

With this question in mind, the current report will highlight the critical role that online learning can play in terms of “freeing up” the time necessary to allow teachers to focus on skill development. We will argue that online learning resources, bolstered by Ed Tech, can be used to lay a common foundation for deeper learning, and can do so in ways that enhance engagement and deepen learning while also allowing for a better personalization of learning. If done right, online learning can be used to help all students come to class with a relatively similar knowledge foundation. With that foundation in place, face-to-face learning can then be used to deepen the knowledge while also giving students structured exercise with the core skills of success, the skills we suspect AI will not possess. Optimally students would be applying the skills and knowledge they are acquiring to real-world “authentic” problems, and whenever possible would perform projects that integrate with their community. Ultimately, the vision presented will be one in which the mode of learning moves progressively from a rich form of the digitally-managed learning of foundational knowledge and skills, to the application of those skills and knowledge within progressively more realistic contexts.

To this end, the remainder of this chapter is organized into the following sections: We begin by discussing the psychology of knowledge transmission versus that of skill development, highlighting how the two occur in very different ways, requiring very different learning environments. We then discuss the merits of online technology-enhanced learning when done well, highlighting how it can bring together multiple avenues of learning with assessment to create a context in which each student is optimally supported as they learn the foundational knowledge of some area, and even foundational skills. Finally, we reimagine face-to-face learning, highlighting the attributes it should have to give our students the sort of practice environment needed to deepen the knowledge and to develop the skills of success to the level needed to truly bring our students the success we all want them to achieve.

The Acquisition of Knowledge is Fundamentally Different from the Acquisition of Skills

We know things, and we know how to do things. In psychological terms, the knowledge we have of the world is called semantic knowledge, whereas the skills we possess – the knowledge of how to do things – is called procedural knowledge (Tulving, 1987). These two forms of knowledge are supported by different memory systems (semantic and procedural memory respectively) and, critically, these two systems acquire information in fundamentally different ways. Semantic knowledge can be acquired through simple and somewhat passive interaction with new information. Attend a great TED talk, wherein an engaging orator provides a well informed and organized presentation, and you will leave with new semantic knowledge that you acquired in 18 minutes while simply sitting and listening. Procedural knowledge is not acquired passively nor quickly. Rather, the acquisition of procedural knowledge requires the learner to engage in the skill being learned, initially at a relatively non-fluent level. With repeated practice, especially within a context that provides structure, support and feedback, the skill will become more and more fluent. With sufficient practice it can become almost “second nature” (Shiffrin & Schneider, 1984).

If we bring this into the educational context one can make the argument that the traditional focus of educational institutions has been to enhance the semantic memory of our students, their core knowledge of the world. At this point though, to be fair to traditional learning practices, we need to differentiate between two sorts of skills. One sort we will refer to as the knowledge-entwined skills. When a student is learning science, in addition to learning the facts of science, they also learn to use the tools of science from microscopes to Bunsen burners, and this includes knowledge of how to do things; procedural knowledge. Yet it is very specific procedural knowledge, procedural knowledge that is tightly entwined with the semantic knowledge, that is the focus. Another example of this sort of knowledge-entwined skills would be learning the order of operations, or how to solve various mathematical problems.

While knowledge-entwined skills are clearly important to those specializing in the specific branch of knowledge, the skills we will highlight here are the more general skills of success. These are assumed to be generalized skills, also sometimes called transferable skills (Assiter, 2017), that can bring one success across a wide range of contexts, and not just work contexts, life contexts as well. Yes, we can highlight how good critical and creative thinking skills will allow one to be valued as a problem solver within their workplace. At the same time, critical thinking helps you find the right life partner (well, it plays some role at least), and creative thinking helps you keep that partner interested. Of course, communication and collaboration skills are always important in ways we will highlight shortly, and nearly everything of value these days happens within teams (Grover, 2005). Perhaps the ultimate transferable skill is the skill of being able to learn and grow as a person in light of data highlighting personal weaknesses (Dweck, 2015) as that skill allows one to grow into almost any situation.

As we and many others have argued, these skills are viewed as critical for our current students if they are to succeed in the modern and future labour markets (Belchior-Rocha et al., 2022), and this was true even before ChatGPT made it even more urgent. Unfortunately, it goes even deeper than that; one can argue that currently our youth are far more behind in their development of some of these skills than was the case for many of the older among us. Notice that some of the skills of success, especially those associated with communication and collaboration, require people to work together in real time. They require an open and comfortable interaction among humans as they try to solve some problem or come up with a creative idea. Thanks in large part to social media, our youth have lived largely in a world of safe, asynchronous, “detached from real nonverbal communication” social interactions to the point where there is now an epidemic of social anxiety (Dobrean & Păsărelu, 2016). They simply have not had the same degree of practice engaging in real-time, face-to-face interactions as we did prior to the ubiquitous use of social media. When they are thrust into such situations, they feel threatened, and their first impulse is to flee (Teachman & Allan, 2007). That is our instinctual response to threat (Winton et al., 1995).

While the highlighting of social anxiety may seem like an aside, it is anything but. If the goal of our teaching is to prepare students to tackle the difficult challenges all around us, that is something they will only do in concert with others. We need an education system that accepts where people are, and where they need to be to succeed. If the skill of effective human interaction is of great value to future success, and if this skill is one that current students lack, all the more reason to make it a priority. Some refer to this specific skill as socio-emotional communication, the ability to communicate with others in ways that strengthen, rather than weaken, our connection to them (Tarasova, 2016).

There is, in fact, very little disagreement within educational advocates around the importance of developing these skills (Boncu et al., 2017). That, of course, suggests that we will alter the way we educate in a manner that will bring a more structured approach to skill development into our curricula. That, in turn, leads to two questions. First, how can we do this? Second, if the solution to the first question requires additional time or resources devoted to skill development, what will we remove from our current approach without sacrificing learning? These are very hard questions, especially given what we know about skill development – that it requires repeated, structured, and active practice with timely feedback (Joordens et al., 2019). It is perhaps not surprising that answers to this challenge have been slow coming. With all humility, we offer one in the sections that follow.

When Done Well, Technology-Enabled Learning Provides a Superior Approach For Transmitting Foundational Knowledge and Skills

The pandemic was not kind to the public’s perception of the merits of online learning (Adnan & Anwar, 2020). When it became suddenly dangerous for children to be in close proximity to one another, educators scrambled to online learning as a form of emergency learning. Prior to this time, those using online approaches tended to be learning experts who knew how to leverage the advantages that online platforms can offer, including how to harness various forms of Ed Tech to enrich and deepen the learning experience. However, during the pandemic, a very basic form of online learning was offered by teachers with little previous experience with, or knowledge of, online learning. In addition, responsibility to manage the learning on the student side was left to parents who themselves had little knowledge of how to do so, and who were often assisting their children as they also attempted to work from home or deal with other pandemic related issues. Simply having the children at home was already stressful, being expected to play part of a teacher role that was completely new to the parent made it even more so (Brown et al., 2020). It should be no surprise, then, that the result of all this was a generally negative view about the educational potential of online learning, and a general embrace of traditional face-to-face learning.

Online learning will play a critical role in the educational system we ultimately describe and, given this, it is important to dispel the notion that online learning is simply a poor substitute for traditional face-to-face learning, at least in terms of knowledge transmission. In fact, there are now a number of meta-analyses that have assessed the impact of online learning (Castro & Tumibay, 2021), and one that has directly considered the relative merits of online versus face-to-face approaches to education (Stevens et al., 2021). Stevens’ et al.’s meta-analysis included 91 comparative research studies within the 2000-2020 period, each of which assessed the extent to which an online versus a face-to-face offering of a course better achieved the desired learning outcomes. The results showed that in 41% of the comparisons, online approaches were found to be superior, in another 41% the method of delivery did not matter, and in 18% the face-to-face approach was found to be superior. This research highlights a number of advantages associated with online learning when it is created with intention, and wielded by educators who understand how to best implement it.

Sometimes the challenges inherent in certain contexts help bring out the skills we need to meet those challenges. One of the challenges of online learning is the fact that often management of the learning experience is left more in the hands of the learners themselves, suggesting that the ability to “self direct” one’s learning may be important to success (Hartley & Bendixen, 2001; Shapley, 2000). Interestingly though, not only does online learning reward those better at self-direction, but one study suggests that experience within online learning contexts may actually help to enhance one’s ability to self-direct (Vonderwell & Turner, 2005). This could be especially important for younger learners and it may enhance their resilience to succeed in contexts where less external support is available (Robinson, 2003).

Rather than pitting one against the other, many who consider the relative merits of online versus face-to-face learning ultimately view them as complementary approaches that could provide especially powerful learning if used together in principled ways (Warner, 2016; Watson, 2008). In fact, the educational system we will propose will follow this same principle, combining online and face-to-face learning in ways that optimally leverages the advantages that each bring to the table. First though, we will focus on online learning, and the critical role it may play in freeing up teacher time and energy, thereby allowing time for the development of the skills of success.

The remainder of this section will highlight some of the key aspects that can allow well-designed online learning to have an impact that can surpass the impact of face-to-face learning approaches. These aspects will be considered within two contexts. First, we will focus on the process of acquiring information, which traditionally happens when teachers present material within their classes. Second, we will focus on the assignments given to students to have them work with the knowledge they have been learning. To be clear, our argument will be that our optimal future education system will rely heavily on online learning to provide a common knowledge-base upon which skills can be developed via synchronous face-to-face interactions.

Acquiring Foundational Knowledge.

Imagine you are a student and, for the first time ever, you are about to learn about the periodic table of elements. How did they come to be known? What figures are associated with the table? How does it advance our understanding of the material things we interact with in the world? How does it allow us to think about our world differently? If a traditional approach to learning is being used, your ultimate understanding of this foundational knowledge will depend heavily on the proficiency of the teacher to present it, and on the extent to which supplementary materials like textbooks can augment that understanding.

Now let us consider this from a digital learning perspective. Before focusing on the way online learning can enhance the learning experience itself, it is worth noting some of the reasons why so many seem to prefer to learn online. These advantages often link to a critical factor that makes some experience intrinsically motivating, a factor termed autonomy (Deci & Ryan, 2012). Specifically, humans enjoy experiences when they feel they have control over the experience rather than being subjected to it and they appreciate convenience. Online learning, as discussed, is believed to give more control over the instruction to the learners (Garrison, 2003). Of course, this also suggests a need to effectively self-regulate as highlighted previously. Thus, often it makes sense to provide some level of structure and scaffolding to help students succeed (Kaur & Joordens, 2021) which in term may enhance their ability to self-regulate going forward (Vonderwell and Turner, 2005).

Focusing more specifically on the learning experience itself, in the hands of talented online-learning designers, that same content can be presented in a manner that creates a much more engaging and personalized experience for the learner, one that puts the student at the center of their learning (Overby, 2011). Consider the following possibilities. The information can be presented in a way that seamlessly combines various forms of multimedia ranging from an expert talking, to animations, to conversations, to charts and data, etc. (Swerdloff, 2016). This is the way students are used to interacting with information. Some of the bits included could involve “bringing the student into the real world” through video clips that show the relevance of what is being taught (Stuckey et al., 2013). Imagine if part way through a presentation on the periodic table someone from Apple describes how they use specific elements in combination to create the screens of the phone that students have in their pocket. It can also allow the information to be presented in a number of different ways, via slightly different modes (visual, auditory) that combine to reinforce the critical points (Clark & Paivio, 1991).

Also critical, while the traditional approach often involves teachers discussing many topics throughout the day, each guided by a curriculum and past experience, online learning resources are more often designed and produced by educational developers who have a deep knowledge of how to engage minds (Sharpe, 2004). They are developed with the intention of being reused, and as such the production is of a higher level, and the care and planning of the learning is often more detailed and evidence-based. For example, we know that beginning a lecture with something that stimulates curiosity can make a student more interested in the learning (Markey & Loewenstein, 2014), we know that humor when used well helps to create a safe learning environment (Pretorius et al., 2020), and we know that presenting things in structured ways with strong scaffolding is critical (Greening, 1998). These and other factors enhance engagement and engagement is the front door to learning (Joordens et al., 2019). Many teachers simply do not know the science of learning to this level and hence are not in the same position to harness it optimally (see Moallem, 1998).

Online learning also has the potential to personalize the learning experience in ways that would be difficult in a traditional classroom (Svenningsen et al., 2018). For example, in the traditional approach all students are exposed to the exact same presentation of knowledge, including the examples used which may resonate with some students but not others.When creating an online learning resource, it is relatively easy to create several versions of video on a given topic, where the different versions may use examples and such that connect the information to specific interests a student may have (music, sport, video games, fashion, etc). The student could then be allowed to choose the video that will most closely connect with their interests (Albrecht & Karabenick, 2018), and giving students choice is itself a facet that also enhances the students sense of autonomy in the learning process (Schutte & Malouff, 2019).

This personalization of learning can also include what some have termed adaptive learning opportunities (Kerr, 2016). That is, it is now readily possible to embed quick assessments directly within the online learning experience (Singleton & Charlton, 2020). This serves several purposes. First, experiencing the assessment gives the students the opportunity to engage in so-called retrieval practice (Roediger & Butler, 2011) an often-overlooked practice that leads to much stronger learning. These embedded assessments also give the students a good signal with respect to whether they have followed the presentation so far, allowing them to review the material again when they do not (Bassili & Joordens, 2008). In addition, it can allow the system managing the learning to know where the student is in terms of their understanding, which can then be used to push students towards supplementary learning materials when needed. For example, let’s imagine our presentation on the periodic table involves the building up of knowledge. We start with some initial bit of content, and then build on it. But we should only build if the student is able to grasp that initial information.The assessment can let us know, and if a student is not grasping the information, then before additional building occurs we can direct the student towards a different and perhaps richer explanation of that initial information. We assess again, and if the student has now acquired that knowledge we bring them back to the building process.

This last point is critical because students will come into the learning experience with varied preparedness for what they are about to learn. By connecting with issues they find relevant, we will enhance engagement and learning. By using assessment wisely, we can be sensitive to where they are in their learning journey and can, to some extent, tailor the learning experience individually for each student “on the fly”. Some students will need more scaffolding than others, and this allows us to provide the scaffolding to those in need without annoying those who are ready to go on. By giving students choice on context within which the learning will be presented (i.e.,the examples used, or real world things connected to) we are enhancing student autonomy, which has been shown to be key to them becoming intrinsically motivated learners (Boud, 2012).

This ability of online-learning to tailor the experience to the student is especially important post-pandemic given the so-called learner-gap issue (Bonal & González, 2020). Some students continued to learn deeply during the pandemic, others were not able to do so for a wide range of reasons. It is impossible for a teacher who is speaking to 30 students to tailor the presentation of material to this extent, to use different examples with different students, to show a deep sensitivity at all times to whether they are understanding or not, and to give students a choice with respect to the contexts they use to present some information.

When the challenge is how to get the most students to a good understanding of some foundational knowledge, especially when they come into the experience with such varied preparedness, online learning has important advantages over face-to-face learning. The ability to tailor the experience, to connect it with what interests the student, to know where students are in their learning journey, and to allow students more autonomy over their learning, these are all important aspects that are nearly impossible to achieve without using online learning.

There is also a strong potential role for AI in terms of personalizing the learning experience. In the March 23, 2023 issue of Fortune magazine, Bill Gates predicts that all of us will soon have a personal AI assistant that organizes our tasks and assists us to get through them efficiently (Pringle, 2023). This concept fits well with Vygotsky’s notion of student learning (Shabani et al., 2010). In Vygotsky’s notion, a teacher is carefully assessing where a student’s proficiency current is, and then they craft learning to enhance that proficiency without asking too much of the student and demotivating them. That is, the teacher is targeting what Vygotsky called the Zone of Proximal Development, the area beyond one’s current abilities but within reach with the right assistance. Thanks to AI, every student might have their own learning coach skilled at structuring learning experiences that allow the student to succeed and grow.

There is another interesting possibility relating to AI and the assessment of knowledge acquisition. Currently we use very poor devices to assess learning, like the ubiquitous multiple-choice test. Each multiple-choice question includes a number of “wrong answers” that we essentially associate with the question as the students do the assessment. Students learn during tests, and they can learn these wrong answers (Rowland, 2014). Perhaps the optimal way to assess knowledge acquisition is through an oral examination, an approach that used to be considered logistically impossible at large scale but thanks to educational technologies is a technique becoming available again (Akimov & Malin, 2020). With the dramatic developments in AI occurring now, one can imagine an AI-based interrogator that could interact with students one on one, ultimately arriving at a quantification of how well they have retained knowledge.

Note, this section has focused primarily on knowledge acquisition, but that should be assumed to also include the knowledge-entwined skills alluded to previously. For example, learning the rules governing how elements interact and reform within chemical contexts is part of understanding elements and appreciating the periodic table. This is where animations can play a critical role, allowing students to see things that could not be seen otherwise, and giving the learning-designer complete control of how these rules are depicted. Similarly, if students are learning how to properly employ the order of operations, immediate embedded assessments can tell us not only if they grasp the rule correctly, but depending on the errors we see it can also provide information about where the student is going wrong. This information can then be used to drive the appropriate follow-up learning. This consideration of knowledge-entwined skills also provides a bridge for us to move our consideration to the assignments students are asked to do as part of their learning experience.

The primary point of this section is simply this; when the right learning expertise is combined with the right technologies, technology-enabled approaches can likely do a far superior job with respect to teaching core knowledge in engaging and interactive ways that can be personalized for the learner. Yes, this was the role of educators in the past, and educators would certainly need to continue to play the role of subject matter experts in the creation of the learning resources. Critically though, they would no longer need to invest the same amount of time presenting this material to students year after year, though they may need to invest some time now and then updating content.

Working with Knowledge While Doing Assignments.

In the introduction we drew a distinction between knowledge, knowledge-entwined skills, and the more general skills of success. The previous section highlighted how technology-enabled digital learning can help all students achieve a relatively common foundational level of core knowledge, and how it can also support the development of knowledge-entwined skills. We now return to a consideration of the more general skills of success. At this point, it is critical to introduce a very simple formula …

Skills = Knowledge + Practice (1)

With respect to knowledge-entwined skills for example, one can be taught the rules governing, say, the order of operations when solving a mathematical problem. At that point the rules are knowledge. As the student now applies that knowledge by repeatedly solving a range of mathematical problems, that knowledge gradually becomes embodied as a skill (Shiffrin & Schneider, 1984). With enough practice, doing things according to the order of operations will become natural, and the student may not bring the actual rules to mind at all. Doing things according to the order of operations has become a skill.

When we ask our students to do assignments that require them to use the knowledge they have learned in active ways a number of pedagogically good things happen. First, with respect to the core knowledge itself, as they apply it they see its significance and how various pieces of knowledge relate. As a result, they now hold that knowledge at a deeper level (VanderArk & Schneider, 2012). It is no longer something they have learned, it is something they have used to solve a problem. Second, these assignments provide a context for students to exercise knowledge-entwined skills by applying them within some specific problem context. This is exactly the sort of practice that helps develop these skills, especially if the context provides structure, support and timely feedback (Pogonowski, 1987).

Once again, we can consider traditional forms of such assignments and contrast them with online forms. Traditionally assignments bring to mind things like book reports, scientific reports, posters, case studies, etc. Students are given some specific task related to some specific thing they are learning, and it’s typically left to each student to create their own composition following some guidelines. Students know that the composition they are creating is simply a means for the teacher to assess their current understanding and proficiency and that it will have no value to anyone once graded.

Online assignments can add elements that can help make the experience of the assignment more engaging and therefore more powerful as a context for learning. For example, multi-media compositions can be more readily accommodated (Pathak, 2001), students can be connected to one another to work in teams (Mayadas & Hultin, 2010) or in simulations where each plays a specific role (Beckem & Watkins, 2012). Given the ability to manage complex logistics on the fly, students can be guided through active learning experiences, and those experiences can again be shaped by the students’ performance throughout (Andersen et al., 2016). It also becomes possible to connect students with community partners facing real problems, supporting a more authentic form of assessment that students find much more engaging (Baasanjav, 2013). As alluded to in the section above, support could be provided to students in the form of Chatbots which can manage communication and help students find their way to the right answers (Clarizia et al., 2018; Colace et al., 2018). Quite simply, in the hands of a great instructional designer, a much more interesting, engaging and personalized learning experience can be created, ultimately resulting in a deeper understanding of core knowledge, and an enhanced proficiency using knowledge-entwined skills.

Critical to the educational system we will ultimately propose, assignments can also be a context within which students can begin to acquire a foundational level of proficiency with the skills of success we will emphasize later in this chapter (Joordens et. al, 2019). To be clear about this, let’s focus on the potential of online peer assessment. There now exist technologies that guide students through a process that works as follows. First students submit a composition in accord with teacher instructions. Next, students see and assess the work of a subset of their peers (say 4) ultimately perhaps rating that work according to some rubric, and then giving each peer some positive feedback and, critically, some constructive feedback. Finally, students see the feedback peers have applied to their own work, and they are given the opportunity to use that feedback to inform a revision of their work for final submission to the teacher. It turns out that it is very challenging to give constructive feedback in a way that will not cause frustration in the receiver, and when one is on the receiving end of feedback it can be hard to get past the negative emotions we naturally feel when seeing a critical analysis of our work. When done well, students are supported as they go through these challenges as they are ultimately learning how to communicate in socio-emotionally proficient ways with other human beings, a core skill of success.

Note that these approaches also give students the opportunity to practice all the skills of success. Consider the challenge of having to give a peer useful constructive feedback, feedback that does not simply expose a weakness in the work, but that also provides suggestions on how to improve. For a student to do this they must first read the work carefully (i.e., receptive communication) while looking out for weaknesses (i.e., critical thought). When a weakness is found they must consider ways in which that part of the work could be improved (i.e., creative thought). Ultimately, they must then communicate this to the peer in a socio-emotionally appropriate way (i.e., effective expressive communication). Doing this for a number of peers adds the repetition that allows these skills to develop. In addition, seeing the work of peers helps students better understand where their work fits and how it could be improved (i.e., metacognitive awareness).

This is exactly the sort of logistically complex assignment that the digital technologies associated with online learning can manage smoothly. One such technology, peerScholar, does not only manage the process of assigning and re-assembling reviews and work in general, it also provides structure and the timely support that helps students succeed, even those with lower initial levels of preparedness (Joordens et al., 2019). For example, before students are asked to give feedback to peers, they see three short micro-learning videos (see videos.peerScholar.com for examples) that inform students of the challenges of giving feedback, and then provide clear suggestions on specifically how to provide feedback in socio-emotionally appropriate ways. Students watch these videos to gain the knowledge, and they then immediately practice that knowledge as they give feedback to peers (Skills = Knowledge + Practice). Other videos assist students in analyzing the feedback they received and using it to guide a revision, others support them as they work within teams.

Assessments are also embedded in the process highlighted above to make the learning even stronger. For example, a student initially gives feedback to four peers, when those peers receive the feedback they assess its quality based on the features they have learned about. The initial student can then see the assessments provided by those they gave feedback to, and they can use that information to improve the feedback they give going forward. As this example shows, assignments within an online learning context can be very rich pedagogically, incorporating many different devices to support the learner, and to give them an experience they are most likely to learn from, and this even extends to the development of core skills of success.

There is one important thing to note at this point. While activities like this can set a skills foundation, the ultimate goal with respect to the development of the core skills of success cannot be achieved through online learning alone. We want students to naturally use these skills in real world, face-to-face, synchronous contexts as they interact with other humans. For example, imagine the student who has just landed a job interview for a position they want very badly. If we succeeded in developing the core skills of success in that student, they will excel in an interview context. They will listen carefully to questions, they will be able to think critically and creatively on the fly, and they will express themselves and their ideas clearly and efficiently. Online peer assessment is asynchronous and anonymous. It provides a fantastic opportunity for laying the foundation for the further development of the skills of success, but ultimately that foundation needs to be built upon, which is where face-to-face learning will come in.

As described above, well-designed online learning experiences can and should be playing a key role in helping to bring students of varied preparedness to a place where they are ready to take their learning deeper, and where they can learn to use the skills of success in real-world ways. The factors described can make learning more engaging and more personal, and the ability to assess on the fly allows us a further degree of adaptability of the learning experience. At the outset of this section we described a meta-analysis suggesting that 41% of the research studies comparing online to face-to-face learning suggested that online was superior, versus 18% suggesting face-to-face was superior. It would not be surprising if, for the latter, a better-designed online learning experience might have reduced that number even further.

In the introduction to this work we suggested that if we are to imagine an educational system of the future that includes an impactful approach to developing the skills of success in our students, then something we are currently doing will have to change to free up the time and energy of educators. Our argument here is that, of all the things teachers do, the laying down of core foundational knowledge and skills is something that can be done better through an embrace of technology-enabled digital learning. The necessary resources and applications may take some time to build but companies exist that are already creating this content, many educational institutions also have groups equipped to help with this as well, and once we have content and an experience we feel is very strong, it can be reused. So yes, there would be an initial phase of getting things in place, but thereafter teachers would not have to spend time and energy teaching the basics to their students. Rather than doing homework in the traditional sense, the students could be expected to spend some time (home or at school) engaging with the digital learning environment.

Going Human and Going Deep

Earlier in this report we highlighted the epidemic of social anxiety that is now so common (Medina, 2021). Consider the face-to-face interview context described above. This is a situation most students would approach with deep anxiety and very low expectations of success (Budnick et al., 2019). This deep anxiety can be explained in terms of a simple lack of practice interacting with other humans in real time and in the real world (Jackson & Everts, 2010). Those who have grown up in the “comfort” of social media often socialize in asynchronous ways that do not provide them with access to nonverbal cues (Remland & Mahoney, 2020). In fact, in general, online learning can be an isolating experience, one that does not provide students rich opportunities to build critical social skills (Suryani et al., 2021). This negative aspect of online learning is one reason why a purely online approach to learning is ill advised as these human interaction skills are critical to student success in life (Beers, 2011).

The missed practice with nonverbal communication is so important. Mehrabien (e.g., 2017) estimated that over 90% of the communication in a face-to-face conversation is nonverbal. Specifically, he gave the so-called 55/38/7 rule; 55% of the conversation is nonverbal communication from the body and face, 38% is nonverbal from voice inflections, and 7% is verbal. These nonverbal cues are typically processed implicitly, and they provide the emotional context for the words. We automatically pick up on things like does our conversation partner like us? Do they think we’re funny, or smart, or attractive, or interesting? Are they in a rush, are they bored, are they lying to us when they talk? Accurate reading of these cues allow us to engage with them respectfully and intelligently, and we use them as feedback that supports the learning of how to have mutually comfortable and respectful conversations.

Sensing someone is bored, or that they don’t really like us is uncomfortable. Having to listen to them carefully and then reply immediately with something that they will consider interesting or relevant is challenging. It’s easier and more comfortable to deal with only the words, and to have time to think before responding. This is the comfort that social media provides, that so many youth are trading for practice in real-time face-to-face conversations, or even real time phone conversations. They are denying themselves practice in reading and understanding all that nonverbals cues convey. When they then find themselves in situations where they must think and react “on the fly”, where their reactions should be informed by the non-verbal cues others are sharing, and where they know their own real emotions are revealed by their non-verbal cues, they feel unprepared, incompetent, they assume things will go poorly (i.e., they suffer from a fear of negative evaluation) and, if given the chance, they will avoid these interactions at all costs (Remland & Mahoney, 2020). Again, denying themselves what is most needed, practice.

These and other factors have lead us all to live increasingly more isolated lives which is a problem because the best predictor of happiness is our number of close social contacts (Cacioppo et al., 2008). Thus, it is not just the case that the modern world puts a premium on one’s ability to use the skills of success, it is also the case that many of our current students are deficient in what may be the most important of these skills, the ability to communicate richly with other humans. If we don’t counter this trend in some way, this deficiency will only grow deeper.

If society is to tackle this issue of better supporting the development of the skills of success, the most obvious place for that to happen is within our schools, colleges and universities. For this to happen in any impactful way, time needs to be specifically devoted to exercising these skills, appropriate learning experiences must be devised and used in an intentional way to develop these skills, and means must be found to quantify these skills (Joordens et al., 2019). Students must also be prepared for the experience, each feeling competent in their knowledge and each having a basic skills foundation to work from.

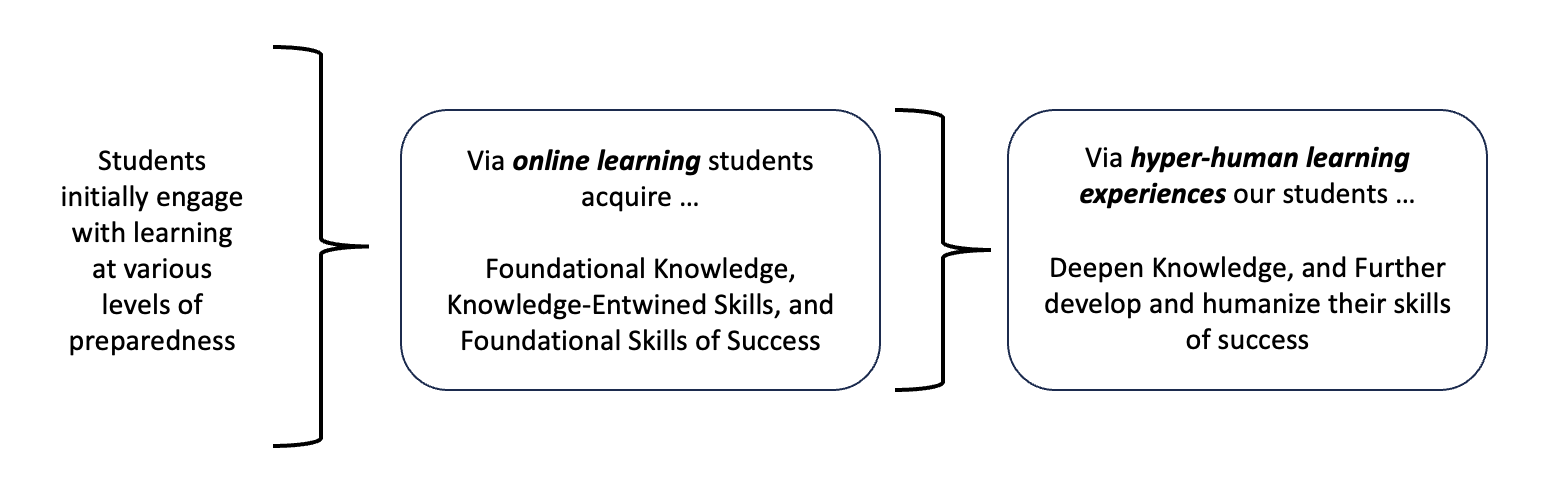

At last then we can depict the educational system we see as most convergent with helping our students succeed in the uncertain future world. As depicted in Figure 1, it involves using well-designed and well-produced online learning to bring a group of students with varied initial preparedness to the point where each has a similar and strong grasp of foundational knowledge, knowledge-entwined skills, and a foundation in the skills of success. With these factors in place, we then move to hyper-human learning contexts. That is, contexts specifically designed to bring students together, with each other and with educators, to work on authentic issues in collaborative ways. Throughout this process skill development is structured and supported through the principle of informed practice. At the same time, knowledge continues to build, but it does so in a less constrained manner, and in a way that is purposeful. That is, as students engage in the various activities, they will need to acquire knowledge that is then combined with their existing knowledge and other new knowledge to reach some relevant goal that optimally will have value beyond the learning experience itself.

Figure 1

Note. Depiction of the core characteristics of an educational system aligned with success in the modern (and future) world.

For example, one skill we would like students to develop is what is formally termed “receptive communication.” It refers to good listening skills which are more rare than most of us realize. Informed practice in this context might look like this. Students would first be taught the concept of active listening, a process that involves showing deep interest in another’s thoughts, listening without judgment, asking questions only for clarification or to provoke more thoughts, etc (see Robertson, 2005). When one has listened well, they are able to repeat what they heard in a way the speaker appreciates. Students would first be given the knowledge related to the skill, they would then be given the opportunity to engage in informed practice; Skills = Knowledge + Practice.

What would informed practice look like in an example like that described above? That’s where the creativity of teachers would come into play. As a community, teachers would be asked to devise and share interesting approaches to exercising core skills in ways that also enhance knowledge within relevant subject areas. Well-designed technology could support the assessment and sharing of practice. If the subject area was engineering, for example, every student could first be asked to deeply learn about some product and the person behind its invention, deep enough to “play that person” in a mock interview. Students could then be paired to simulate a reporter interviewing that person about their creation, each taking turns playing the role of reporter versus inventor. The reporter’s main task would be to practice the critical life skill of active listening in this interaction (Rost & Wilson, 2013), which works well because reporters model something akin to active listening regularly. In the interaction that follows, which would be unscripted, the reporter would try to learn more and more about the inventor, and the problem they were focused on in an attempt to “guess” the product. Both would gain experience within a human face-to-face interactions, and that interaction would occur in a context that is spontaneous and synchronous, while also being “safe” in the sense that it’s controlled role playing and a little fun. Other students might be asked to listen with the goal of identifying the mystery product, entering their guess via some platform and perhaps being rewarded in some manner for listening well themselves. As that example highlights, the focus would be on giving students practice working with others, communicating with others, and essentially addressing their lack of practice in face-to-face real time human interactions in the manner that is focused on developing their core skills of success, while also building upon their knowledge.

Lest that last point be lost in all the emphasis on the skills of success, skills are best developed in authentic contexts (Lombardi & Oblinger, 2007) and some of the most effective learning contexts, such as problem-based learning (Allen et al., 2011), require students to acquire new knowledge in a purposeful way. To, in some manner, help solve a problem. This is how we seek knowledge after our formal education, so this is a great skill to develop. It does mean the specific knowledge a given student acquires will depend on the activities they performed, which implies that if we wish students to enhance their knowledge in some specific areas we only need design activities that should bring them to that knowledge.

The remainder of this section will focus more on what hyper-human learning could look like, but before going there we wish to make a few assumptions clear with respect to the approach depicted above. The natural inclination might be to think of this in terms similar to those involved in a “flipped classroom” (Akçayır & Akçayır, 2018). There are certainly parallels, although we are focused on the institutional level rather than on the class level. However, in a flipped classroom the usual assumption is that students do their online learning as homework, and come to class for something like the hyper-human learning we have in mind. Note that while this is one approach, another possibility is that the digital learning also happens within the school, but simply does not require the same level of teacher engagement. Teachers could be focused primarily on the hyper-human learning, while educational support workers (or AI) could assist students in accessing and working with the online resources. That said, for students who require more digital learning to keep up with their peers, that could indeed happen outside of the school.

This approach might also bring to mind the notion that the teacher must move from being the “sage on the stage, to the guide on the side” (King, 1993). But this also does not truly fit our vision. We still see the teachers as sage’s of a sort, but sages with a focus on how best to develop the skills of success while also building knowledge in active ways. By analogy, consider non-academic contexts where skills are taught. Is the martial arts instructor a “guide on the side”? Perhaps, during the periods where students are practicing the skills. But that instructor initially teaches those skills as knowledge (skills = knowledge + practice). They first describe and demonstrate how to perform the skill well. They also ensure the context of learning has the attributes that will make the practice most effective when students are asked to put their new knowledge into practice. In a real sense, they are sage’s of skill development, and their craft is one of informing, and then supporting, skill development in the most evidence-based manner.

What would this hyper-human learning look like? Well first, it should include a wide range of specific learning activities, but they all should have certain characteristics in common. First, as suggested by the name we gave them, everyone one of these activities should involve students working with others. In a real workplace, perhaps only some of the work is collaborative. That’s why we refer to this as “hyper-human”. To overcome deficiencies and exercise the core skills of success the optimal situation would be to have every learning context be collaborative. Second, these contexts should be ones that provoke the students to engage the skills of success in their work. Thus, the premium should be on activities that ask students to think critically, perhaps while identifying issues in some context. They should be asked to think creatively, perhaps to come up with solutions to those issues. They should involve them learning how to effectively listen to and learn from others, while also being asked to represent their own ideas and perspectives. They must involve students working together, preferably within teams, to learn the skills of collaboration. They also should involve reflective opportunities for students to consider their strengths and weaknesses, and to devise ways of strengthening areas where there is need. Whenever possible, these experiences should involve students working with entities outside of their educational institution, preferable on authentic projects where their work could truly make a difference (Smith, 2016). That is, this hyper-human learning is meant to be a bridge between educational institutions and the world beyond, and that bridge should be part of the learning context itself.

Innovative educators have already identified learning contexts that fit this notion quite well. For example, experiential learning projects involve students working in teams to help some external organization tackle a challenge they are facing (Hearn et al., 2021). For example, the first author of this chapter recently had students in his very large Introduction to Psychology course work with an organization called Swab the World. As it turns out, over 80% of the humans in the world are non-Caucasian, yet the stem cell databases used to connect patients with life-saving donors in Canada is over 70% Caucasian. In this case culture matters in terms of finding a match, which means that currently Caucasian patients have a much higher chance of finding a stem cell donor. Students in this class worked in teams of 4 to create public service announcements intended to inform young non-Caucasians about this disparity, and to encourage them to consider swabbing their cheek (i.e., adding their DNA to the database). Doing so required students to work creatively within collaborative groups on a project that they cared about, exercising all the core skills of success in the process.

Other powerful approaches include problem-based learning (Wood, 2003), team-based brainstorming (Maybee et al., 2023), simulation contexts (Kincaid et al., 2003) and many more. For example, recalling the interviewing context described earlier, students could perform simulated interviews, ultimately experiencing the interview from both sides. Students who have both created (and asked) interview questions, while also being the one interviewed at times, are much more likely to go into future interviews confidently. If this kind of hyper-human learning becomes a critical part of the learning process, no doubt educators will come up with many more ways of bringing students together to perform tasks of relevance that exercise their core skills of success. The more varied the contexts, the more the natural use of these skills will generalize (Scheeler, 2008). Also, the more authentic the contexts of practice, the less daunting will be the leap from education to the world of work (Herrington et al., 2014).

Note, there may be a critical role for generative AI to play here as well. When students are first learning skills like active listening, they could practice those skills by interacting with an AI bot. These bots do not judge, and thus there should be less fear of negative evaluation. The bots do not get bored, so a student could practice over and over. The bots could also be taught the “rules” that the students are trying to practice, and could give feedback based on how well those rules were followed. Even in the interview context, its possible a “committee of bots” could be created to simulate an interview committee, each asking questions in turn, etc. Once again, the safe nature of the AI context (no one but you sees or cares about your failures) could allow them to provide an optimal practice context.

As a final example of the sort of contexts that we feel should become an essential part of our future approaches to education, consider entrepreneurship education (Von Graevenitz et al., 2010). There is perhaps no better context for engaging the skills of success than having students work within teams to brainstorm and pitch entrepreneurial ideas, and perhaps to even bring those ideas to life. Entrepreneurship, of various types, now forms a core part of the future of work, and when we have students experience this the relevance of their learning is obvious. They also learn important things missing from traditional approaches to learning. High on the list would be the notion that in contexts like this, failure is simply part of the journey. Accepting that and, critically, learning from it is part of every entrepreneurial experience, and modeling that in our education system is so important (Jungic et al., 2020). In fact, it provides a direct analogy for personal growth wherein we all must learn to “pivot strategies” from time to time.

One final note. Throughout this section we focused on the humanization of the core skills of success, but that does not mean knowledge acquisition has stopped. Far from it. In order to perform the various challenges we give them, students will indeed need to acquire new knowledge and to combine it with existing knowledge. What specific knowledge they interact with will be less controlled than it is traditionally as they would seek the knowledge that they need at the time they need it, and for a specific reason. This constructivist approach to knowledge acquisition is a core part of the power of problem-based learning, and it is much more aligned with how they will find and use knowledge in their post-academic life (Wilson, 2017). Hence our argument that knowledge will only deepen as the skills of success develop.

K12 versus Higher Education?

Throughout this report we’ve been speaking of students and institutions of public education in general, as if both are equivalently relevant to the educational approach being proposed. To some extent this is true, though we would argue that a move to the sort of system we suggest would and should be traversed at both levels. That said, to the extent one or the other would benefit more, or perhaps should be the initial focus of change, we would argue that making changes at the K-12 level first would be most impactful and sensical.

It is important to note that there is little to no research directly contrasting the K-12 and Higher Ed segments in terms of any of the findings highlighted throughout this work. Given that most of the research is conducted by professors with labs and classes at colleges and universities, the most convenient sample typically comes by way of undergraduates within Higher Education. Yes, some researchers, especially within departments of education, also do research with K-12 populations, but this research is less plentiful, and researchers working with samples in both sectors are virtually non-existent. As a result, much of what follows is speculative and based on general psychological principles rather than specific research findings.

With that caveat in mind, we argue that the sort of change we are arguing for to institutions of public education would have their biggest impact at the K-12 level, and that making the change first at the K-12 level would make the most sense. We will make this argument first around the two main parts of the revised educational approach we present; optimally using online learning to get all learners to a place of similar competence with foundational knowledge, and using face-to-face time in a more formal and structured way intended to develop the core human skills related to success.

Foundational Knowledge and Online Learning.

Earlier in this report we presented data suggesting that, through well thought out and produced online learning resources, it is possible to present information in ways that are more engaging for students living in the YouTube generation and to make these resources available to students with a flexibility that would allow learners at different levels of competency to negotiate the knowledge in a manner that worked for them. Thus, a higher level of personalization and engagement is possible. Different students may ultimately take different paths as they learn foundational knowledge, with some perhaps watching more videos to negotiate the knowledge more gradually, or perhaps watching videos that present the knowledge in a context they find more relevant and interesting. The potential result is that, while students may take different paths, they may all arrive at a point where they have the foundational knowledge in place with similar levels of competence.

A key term in the previous paragraph is “foundational”. The advantages highlighted above set the foundation for future learning, and give all students a relatively equitable chance of building upon that knowledge through future learning. It simply makes sense that this sort of approach would work best at the very earliest stages of learning. If we wait until students reach college or university, we would simply miss many students who were not able to set their foundation and thus never made it into colleges or universities at all! It is also the case that the knowledge we teach is the most “set” for lower levels of education, and thus the time spent producing fantastic online learning resources around something like the basics of algebra can yield the highest return. This could be less true for an online series related to, say, The History of Psychology, a course only a small subset of students would encounter.

Developing the Core Skills of Success.

Of course, a key aspect of our proposal is that, in addition to providing an enhanced approach for teaching foundational knowledge, the use of well-crafted online resources could free up teacher time, allowing them to focus their efforts on managing student-centered active learning opportunities designed specifically to exercise, and thus develop, key skills of success. These skills include critical and creative thought, effective two-way communication, the ability to work well within teams, and even the skills of being a self-directed learner (and human!). Once again, these skills are becoming ever more critical within a dynamic labour market in which artificial intelligence is quickly replacing jobs that can be done without the need for such skills.

As we have argued throughout, developing a skill like critical thought is not different, in principle, from developing a skill like those involved in playing a musical instrument well. Such skills only develop with repeated practice, preferably within a structured learning environment that provides support and timely feedback. If you would love for your child to be an amazing athlete, when would you begin this sort of formal structured practice? Would you wait until the child was 18 or 19, around the age when many students begin college or university? Likely not, as any sports-parent knows, to reach the highest level of any skill the structured practice should begin as soon as the child is ready to listen and learn. Thus, in a world where skills determine ultimate success, we should begin developing these skills as early as possible, certainly more within the K-12 range than the Higher Education range.

Summary

Our youth live in a world where many of the skills that are most relevant to their success are under-developed. What’s more, to the extent we can see the future of work, it will be one wherein these various skills become even more critical as AI takes over jobs that can be done without them. Our educational systems provide students with knowledge but, in the opinion of most educational theorists, we are not doing enough to help students develop their core skills of success (e.g., Fullan, 2014). These skills do not only help them succeed in their chosen career, but these are the human skills involved in working with others effectively, and their development positively impacts all aspects of a person’s life. That said, developing skills takes time, energy, and a serious commitment to creating a context of practice needed to properly support skill development. The learning context should be a bridge between schools and life thereafter. For that to happen schools will have to fundamentally change as serious time and effort will need to be invested in the creation and management of skill-building educational experiences. If we are to make skill development a priority, we need to free up the time and energy of teachers.

We argue that technology-enabled learning can help us free up teacher time in a way that optimizes the educational experience for students. Well-constructed digital learning experiences can take over in terms of teaching students foundational knowledge and knowledge-entwined skills, and can do so in ways that enhance our ability to serve students with varied levels of initial preparedness. They can also lay the groundwork for the development of core skills of success. Having gone through the digital learning process, students would be more consistent in terms of the skills set, all with a strong foundation upon which to build.

The teachers could then focus on skill development by managing interactive and collaborative learning experiences designed to have students exercise the core skills of success in a human real-time manner. This would indeed be a different role, but given that students often enjoy the freedom and social interactions common within these sorts of learning environments, teachers may also be caught up in the fun of learning. If the results of the learning have value and relevance beyond the classroom, then all involved will feel a sort of pride and community connection that is also key to student success and happiness.

Finally, we also argue that this transformation of education would most optimally begin at the K-12 level, thereby accomplishing two critical goals. First, the use of well-crafted online resources would help us personalize learning in such a way that all students could be brought to approximately the same level of foundational knowledge. This would result in a more equitable educational experience that should allow all students to then build upon that foundation in effective ways. Second, the early focus on skill development would give students lots of time to continue to hone their skills of success as they move through our public education systems. The result of all this should be students who graduate with the knowledge they need augmented by a strong set of skills they can use to work with that knowledge, and with others, to have positive results for themselves and all that their work impacts.

It is a difficult time to be calling for major educational reform. Society in general has been through a very challenging time, and many of us are feeling burnt out, or close to it (Queen & Harding, 2020). It is hard to rise to the challenge of large-scale change when feeling burnt out. That said, it is the responsibility of educators to do the best we can to prepare our students for success and given the dramatic acceleration of AI the need for reform feels stronger than ever. Well-constructed digital-learning has advanced to the point where it can help us get to a place where the face-to-face time we spend with students can be strategically used to help develop the skills our students need. The opportunity is now available to do what educational reformers have been calling for for a long time, making skill development a core part of the learning experience so that when our students graduate, they are ready to meet the challenges of the future.

References

Able, J. R. & Deitz, R. (2013, May 20). Do big cities help college graduates find better jobs? Liberty Street Economics. https://libertystreeteconomics.newyorkfed.org/2013/05/do-big-cities-help-college-graduates-find-better-jobs/

Adnan, M., & Anwar, K. (2020). Online learning amid the COVID-19 pandemic: Students’ perspectives. Online Submission, 2(1), 45-51.

Akimov, A., & Malin, M. (2020). When old becomes new: a case study of oral examination as an online assessment tool. Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education, 45(8), 1205-1221. https://doi.org/10.1080/02602938.2020.1730301

Akçayır, G., & Akçayır, M. (2018). The flipped classroom: A review of its advantages and challenges. Computers & Education, 126, 334-345. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2018.07.021

Albrecht, J. R., & Karabenick, S. A. (2018). Relevance for learning and motivation in education. The Journal of Experimental Education, 86(1), 1-10. https://doi.org/10.1080/00220973.2017.1380593

Allen, D. E., Donham, R. S., & Bernhardt, S. A. (2011). Problem‐based learning. New directions for teaching and learning, 2011(128), 21-29. https://doi.org/10.1002/tl.465

Amelia, R., Kadarisma, G., Fitriani, N., & Ahmadi, Y. (2020, October). The effect of online mathematics learning on junior high school mathematic resilience during covid-19 pandemic. In Journal of Physics: Conference Series (Vol. 1657, No. 1, p. 012011). IOP Publishing.

Andersen, P. A., Kråkevik, C., Goodwin, M., & Yazidi, A. (2016). Adaptive task assignment in online learning environments. In Proceedings of the 6th international conference on web intelligence, mining and semantics (pp. 1-10). https://doi.org/10.1145/2912845.2912854

Andrews, J., & Higson, H. (2008). Graduate employability,‘soft skills’ versus ‘hard’business knowledge: A European study. Higher education in Europe, 33(4), 411-422. https://doi.org/10.1080/03797720802522627

Assiter, A. (2017). Transferable skills in higher education. Routledge.

Baasanjav, U. (2013). Incorporating the experiential learning cycle into online classes. Journal of Online Learning and Teaching, 9(4), 575-589.

Bassili, J. N., & Joordens, S. (2008). Media player tool use, satisfaction with online lectures and examination performance. Journal of Distance Education, 22(2), 93-107.

Beckem, J. M., & Watkins, M. (2012). Bringing life to learning: Immersive experiential learning simulations for online and blended courses. Journal of Asynchronous Learning Networks, 16(5), 61-70.

Beers, S. (2011). 21st century skills: Preparing students for their future. STEM. https://www.yinghuaacademy.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/10/21st_century_skills.pdf

Belchior-Rocha, H., Casquilho-Martins, I., & Simões, E. (2022). Transversal competencies for employability: From higher education to the labour market. Education Sciences, 12(4), 255. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci12040255

Bonal, X., & González, S. (2020). The impact of lockdown on the learning gap: family and school divisions in times of crisis. International Review of Education, 66(5), 635-655. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11159-020-09860-z

Boncu, A., Costea, I., & Minulescu, M. (2017). A meta-analytic study investigating the efficiency of socio-emotional learning programs on the development of children and adolescents. Romanian Journal of Psychology, 19(2). doi: 10.24913/rjap.19.2.02.

Brown, S. M., Doom, J. R., Lechuga-Peña, S., Watamura, S. E., & Koppels, T. (2020). Stress and parenting during the global COVID-19 pandemic. Child abuse & neglect, 110, 104699. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2020.104699

Boud, D. (2012). Developing student autonomy in learning. Routledge.

Budnick, C. J., Anderson, E. M., Santuzzi, A. M., Grippo, A. J., & Matuszewich, L. (2019). Social anxiety and employment interviews: does nonverbal feedback differentially predict cortisol and performance?. Anxiety, Stress, & Coping, 32(1), 67-81. https://doi.org/10.1080/10615806.2018.1530349

Cacioppo, J. T., Hawkley, L. C., Kalil, A., Hughes, M. E., Waite, L., & Thisted, R. A. (2008). Happiness and the invisible threads of social connection. In The science of subjective well-being (pp.195-219). Guilford Press.

Castro, M. D. B., & Tumibay, G. M. (2021). A literature review: efficacy of online learning courses for higher education institution using meta-analysis. Education and Information Technologies, 26(2), 1367-1385. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10639-019-10027-z

Chalkiadaki, A. (2018). A systematic literature review of 21st century skills and competencies in primary education. International Journal of Instruction, 11(3), 1-16.

Chui, M. (2023, August 1). The state of AI in 2023: Generative AI’s breakout year. McKinsey & Company. https://www.mckinsey.com/capabilities/quantumblack/our-insights/the-state-of-ai-in-2023-generative-ais-breakout-year

Cho, M. H., & Shen, D. (2013). Self-regulation in online learning. Distance education, 34(3), 290-301. https://doi.org/10.1080/01587919.2013.835770

Clarizia, F., Colace, F., Lombardi, M., Pascale, F., & Santaniello, D. (2018, October). Chatbot: An education support system for student. In International Symposium on Cyberspace Safety and Security (pp. 291-302). Springer, Cham.

Clark, J. M., & Paivio, A. (1991). Dual coding theory and education. Educational psychology review, 3(3), 149-210. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF01320076

Colace, F., De Santo, M., Lombardi, M., Pascale, F., Pietrosanto, A., & Lemma, S. (2018). Chatbot for e-learning: A case of study. International Journal of Mechanical Engineering and Robotics Research, 7(5), 528-533. doi: 10.18178/ijmerr.7.5.528-533

Deci, E. L., & Ryan, R. M. (2012). Self-determination theory. Handbook of theories of social psychology, 1(20), 416-436.

Dobrean, A., & Păsărelu, C. R. (2016). Impact of social media on social anxiety: A systematic. New developments in anxiety disorders, 129. https://dx.doi.org/10.5772/65188

Dweck, C. (2015). Carol Dweck revisits the growth mindset. Education week, 35(5), 20-24.

Fullan, M. (2014). Teacher development and educational change. Routledge.

Garrison, D. R. (2003). Self-directed learning and distance education. In M. G. Moore & Anderson (Eds.), Handbook of distance education (pp. 161-168). Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum.

Goggin, D., Sheridan, I., Lárusdóttir, F., & Guðmundsdóttir, G. (2019). Towards the identification and assessment of transversal skills. In INTED2019 proceedings (pp. 2513-2519). IATED. doi: 10.21125/inted.2019.0686

Green, F., & Henseke, G. (2016). The changing graduate labour market: analysis using a new indicator of graduate jobs. IZA Journal of Labor Policy, 5(1), 1-25. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40173-016-0070-0

Greening, T. (1998). Scaffolding for success in problem-based learning. Medical Education Online, 3(1), 4297. https://doi.org/10.3402/meo.v3i.4297

Grover, S. M. (2005). Shaping effective communication skills and therapeutic relationships at work: The foundation of collaboration. Aaohn journal, 53(4), 177-182. https://doi.org/10.1177/216507990505300408

Hart, C. (2012). Factors associated with student persistence in an online program of study: A review of the literature. Journal of interactive online learning, 11(1).

Hartley, K., & Bendixen, L. D. (2001). Educational research in the Internet age: Examining the role of individual characteristics. Educational Researcher, 30(9), 22-26. https://doi.org/10.3102/0013189X030009022