Darryl Isbister

Indigenization and the Future of Post-Secondary Education

Darryl Isbister

University of Saskatchewan

Traditional Knowledge is the knowledge resulting from intellectual activity in a traditional context, including innovations, know-how, practices, and skills that are developed, passed on through generations, and that form the cultural and spiritual identities of Indigenous communities. As Indigenous communities are the guardians of their Traditional Knowledge, the access and use of Traditional Knowledge is solely their discretion and in accordance with licenses that they have chosen to apply. The licensing for this chapter is CC BY-NC 4.0. To view a copy of this license, visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/ ]

What is Indigenization of post-secondary education?

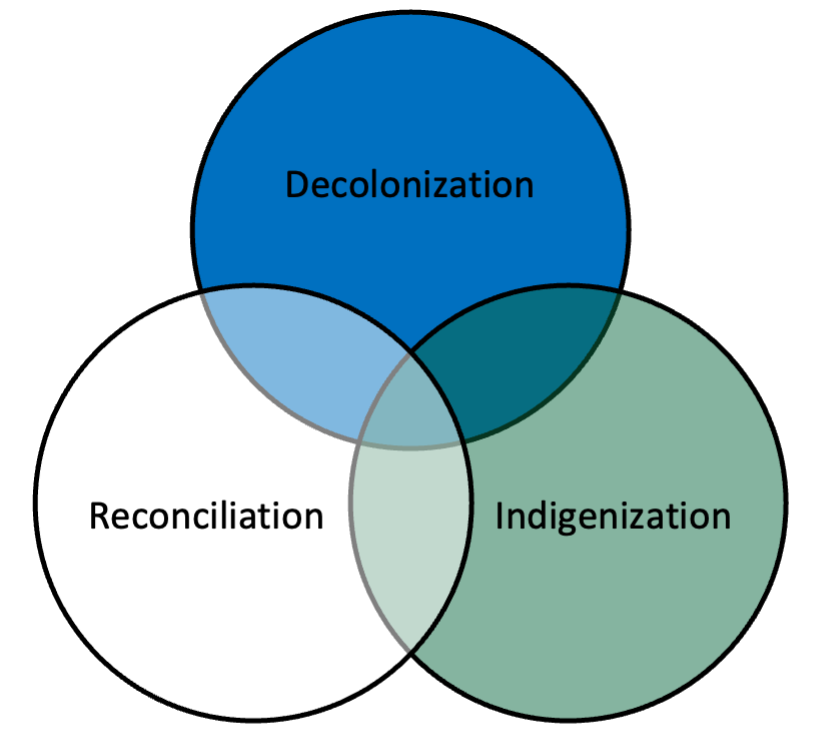

Indigenization, decolonization , and reconciliation (IDR)

Indigenization, decolonization , and reconciliation (IDR) are three terms used to describe actions taken to address the challenges faced by Indigenous people in post-secondary education. A commitment to IDR across all levels of the post-secondary education system provides educators and decision-makers with opportunities to actively engage in transformational change. Post-secondary institutions have a responsibility to support educators and decision-makers in examining the historical and current models of education and applying innovative practices to champion Indigenous pedagogy.

When envisioning the future of post-secondary education for Indigenous learners, understanding past practices is fundamental for influencing future approaches. Indigenous-informed education practices will lead the way and change the experience for First Nation, Inuit, and Métis learners. Simultaneously, non-Indigenous learners and educators will benefit from recognizing the value of Métis, First Nation, and Inuit ways of knowing and doing.

Examining how institutions define IDR will support educators in identifying who will lead the change and in locating partners and allies. Educators committed to effecting change will consider personal context and location and actively collaborate with Elders and Knowledge Holders. The words shared by Bob Joseph (2018), guide and enrich our understanding of education practice and IDR.

- Indigenization “…is about incorporating Indigenous worldviews, knowledge and perspectives into the education system, right from primary grades to universities” (Joseph, 2020, Para. 6).

- Decolonization “…requires non-Indigenous Canadians to recognize and accept the reality of Canada’s colonial history, accept how that history paralyzed Indigenous Peoples, and how it continues to subjugate Indigenous Peoples.” (Joseph, 2020, Para. 2).

- Reconciliation “… is about establishing and maintaining a mutually respectful relationship between Indigenous and non-Indigenous peoples in this country.” (Joseph, 2018, Para. 5).

At the heart of these definitions is the understanding of the pivotal role relationships play in creating place and space for Indigenous learning. The work will take time, is complex, and is not the exclusive responsibility of Inuit, Métis, and First Nations. Together, we will embark on a transformative journey into the future of post-secondary education – one where Indigenous knowledge threads its way through the fabric of higher learning, fostering innovation, cultural diversity, and a reimagined academic landscape. This chapter aims to support those interested in understanding why we should engage in IDR, how to infuse IDR into teaching practices, and what educators can do to positively impact lived experience of Indigenous people.

Pause for Thought

- Where has my knowledge of First Nation, Inuit, and Métis come from? What biases may exist in the knowledge I have acquired?

Reflect on when you first recall learning about Indigenous people. Who were the people tasked with sharing this knowledge? What was their social position? Consider the implications of the unintended bias shared by the experience. - How can we keep our ongoing work around Indigenization and decolonization authentic and from the heart, as opposed to a checklist of things to do?

Ponder the deeper motivations behind your efforts. Authentic engagement involves more than ticking boxes; it requires a commitment to understanding, respect, and genuine collaboration with Indigenous communities. Reflect on how you can approach this work with sincerity and empathy. - How do you see reconciliation applying to your own life?

Consider how reconciliation extends beyond the classroom. Reflect on your personal connections to Indigenous histories, cultures, and experiences. - Why should I Indigenize and decolonize teaching & learning?

Delve into the reasons behind Indigenization and decolonization. Recognize that it is an invitation to honor Indigenous perspectives, contributions, and knowledge. Reflect on how Indigenization promotes equity, enhances learning experiences, supports reconciliation, and aligns with holistic approaches to learning.

Why You Should Engage in IDR – Imperatives for Change

The higher education learning community, as it currently stands, must participate in thoughtful self-reflection to enhance support for Inuit, Métis, and First Nation learners. Recognizing the need for change can often be difficult for those who have not experienced the realities faced by Indigenous communities. The Western traditional model of education often employs a one-size-fits-all approach to learning that has appeared to work. However, this belief stems from the dominant culture creating a system built for the needs of their community. Increasing an understanding of the experience faced by First Nation, Inuit, and Métis learners will improve outcomes and transform the learning story. To enhance the education system, educators must embrace practices that meet the learning needs of Métis, First Nation, and Inuit learners.

In 2009, the Saskatchewan Ministry of Education created a document to support Indigenous education. Inspiring Success: Building Towards Student Achievement provided K-12 educators with compelling reasons to transform their teaching practices. The four imperatives outlined in this document reinforced educators’ understanding of the need for change. Importantly, these imperatives have the potential to positively impact not only K-12 education but also post-secondary institutions.

The imperatives – moral, economic, and demographic – serve as guiding principles for decision-making in K-12 education with the intent of improving completion rates and overall success for Indigenous learners. In 2018, the Ministry of Education engaged in further consultation with organizations, Elders, and Traditional Knowledge Holders from across the province. The result was a renewed document titled; Inspiring Success: First Nations and Métis PreK – 12 Education Policy Framework. The imperatives remain present in the new document, with additional imperatives becoming part of the strategy after consultation with the community.

Examination of the imperatives provide educators with a reason they should engage in IDR and a foundation on which to build Indigenous pedagogy into their current practices.

A. The Cultural Imperative

The impact of the Residential School system on Inuit, Métis, and First Nation learners has been significant. Recognition of this harm has become more prominent since December 2015 with release of the Final Report of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC) of Canada and the 94 Calls to Action. A positive first step in the healing process is recognizing the impact of learning alongside First Nation, Inuit, and Métis. Realizing a commitment to healing this reality begins with an examination of the cultural imperative. The cultural imperative affirms Indigenous identity and knowledge transfer from both historical and contemporary pedagogy.

“Through their learning experiences, Indigenous learners need to see and hear that they, and their families, communities, histories, and cultures are valued and important.” (Chrona, 2022, p. 24).

The gift of knowledge shared by Elders and Knowledge Holders reduces the emotional impact on learners of Métis, First Nation, and Inuit ancestry. Learning supported with Indigenous culture will also open the door for the inclusion of Inuit, Métis, and First Nation ways of knowing and doing. All students will benefit from the affirmation of Indigenous cultural knowledge and begin to reduce barriers and stigma, the result of colonization. We will also begin to recognize that Indigenous ways of knowing and doing are contemporary, not restricted to historical understandings.

B. The Ecological Imperative

In 2015, recognition of the land and acknowledgement of the original inhabitants became part of the public response to the TRC’s Final Report. Indigenous learning relies on the essential connection to the land and the gifts it offers. The land shares a story that builds knowledge in a variety of ways. Educators can model this learning and use the land to support experiential learning and engagement of learning. An increased connection to the land by learners will benefit the land itself. These connections can work to address the continuing impact of climate change, water crises on First Nations, and loss of habitat. The ecological imperative underscores the value of embedding First Nation, Inuit, and Métis knowledge and action in instruction, assessment, and curriculum.

C. The Moral Imperative

The education reality experienced by Métis, First Nation, and Inuit learners is not a manifestation of recent practice. In Saskatchewan, the 2021 high school completion rates for Indigenous students who finished school within three years of entering grade 10 was 45 per cent, the five-year completion rate was 62 per cent (Simes, 2023). While this represents progress compared to previous years, the numbers are static. In contrast, non-Indigenous students achieved significantly higher graduation rates during the same period. Eighty-nine percent for the three-year rate and 92 percent for the five-year rate. The intent here is not to compare one group to another, rather to highlight the experience for both.

The moral imperative should drive decision making for determining the responsibility of educators and institutions implementing change. When confronted with the reality of Inuit, Métis, and First Nation learners a reaction is often ‘Indigenous learners must learn to fit into the world of higher education,’ this narrative must change. Educational institutions bear the responsibility to respond to the inequity that it has perpetuated, creating a more inclusive future.

D. The Economic Imperative

In 2013, The Gabriel Dumont Institute, with Eric Howe of the Howe Institute, authored a report outlining the economic impact of bridging the education gap. The goal of the document was to provide an understanding of the overall benefit for First Nation, Inuit, and Métis learners graduating high school and pursuing post-secondary education. Howe gathered data based on program completion (degree or diploma), Indigeneity (First Nation and Métis), and gender. Howe (2013) found that the benefit of completing high school for an Indigenous learner is almost $300 000 more in lifetime earnings (Howe, 2013, p. 6). These lifetime earnings could increase further if learners successfully complete post-secondary education.

Howe (2013) also examined the social impact of education completion for Métis, First Nation, and Inuit learners. He predicted closing the graduation achievement gap would provide a social benefit to the province of Saskatchewan of about ninety billion dollars (Howe, 2013, p. 35). This number would most certainly be higher if learners achieved success at the post-secondary level as well. The economic imperative articulates quality of life criteria for changes to education in support of Inuit, Métis, and First Nation learners.

E. The Historical Imperative

The Western narrative describes a shared history between Indigenous and non-Indigenous peoples. We must begin to question that narrative given the lived experience of Indigenous people on this land. Western culture has been the predominant voice about the history of the land since contact which highlights how difficult it is to call this history shared. First Nation, Inuit, and Métis must have opportunity to tell their stories and history. Providing access to platforms with Indigenous voice for non-Indigenous historians need to become part of the conversation.

Using the term, ‘shared history’ minimizes the reality that exists between Indigenous and non-Indigenous relations. The dominant narrative attempts to describe the cohabitation of cultures as living a peaceful coexistence with mutual respect. The reality is a different story. Strained relationships have created historical and contemporary challenges to the coexistence of cultures. A ‘shared history’ also implies that the story has voice from all parties involved. The history as told, primarily involves non-Indigenous voice speaking for all. Pages of history such as the signing of the Numbered Treaties in the West or the Riel Resistance are different when we hear from First Nation or Métis Elders and Knowledge Holders. Historically, it is necessary that we recognize the dual history experience and provide voice for the Métis, First Nation, and Inuit. It is imperative that Indigenous voice be present when discussing history.

An essential understanding of the work needed to achieve the change centers on relationships with Indigenous communities. To support learning for Inuit, Métis, and First Nation, we need to consult them to find meaningful strategies.

Pause for Thought

- Which imperative is most connected to you and your work?

Reflect on how each of these imperatives has contributed to the lived reality for Indigenous peoples of this land. How can changing the current reality affirm Indigenous knowledge and reduce barriers to success? - How can higher education advocate for change at all levels of education?

This work will be successful when everyone involved in education recognizes the importance of systemic change. Reflect on how accomplishing this can be in partnership with Indigenous and non-Indigenous parties. - How does higher education work with community to protect Indigenous knowledge and the people responsible for its integrity?

Reflect on how the education system has a responsibility to ensure that Indigenous knowledge maintains safety in a complex world. How will higher education affirm the knowledge and work to have holders of the knowledge become regular participants in campus activities? - How will education repair relationships and work toward enhanced inclusion of Indigenous peoples in higher education?

Reflect on current practice and how enhancement would change the reality for Indigenous and non-Indigenous learners. Explore ways in which Indigenous pedagogy can become part of learning in higher education.

Indigenization, Decolonization, and Reconciliation – Where do we Begin?

Providing a context for how education has defined IDR will influence future practice. Whether we use the definitions of IDR provided, access local definitions, or engage with Elders and Knowledge Holders to create definitions, understanding these terms will sustain education renewal. To reduce barriers to implementation, we want to identify which group best provides strategic leadership for the components of IDR.

Indigenization – non-Indigenous educators may require assistance in finding a place where they are actively involved with Indigenization. Growth of Indigenous voice since the emergence of Idle No More, has added a layer of uncertainty to the experience of cultural appropriation. We recognize that First Nation, Inuit, and Métis will provide leadership for Indigenization and invite non-Indigenous friends and allies to walk alongside. The desire is to achieve “the respectful, meaningful, ethical weaving of First Nations, Métis and Inuit knowledge, lived experiences, worldviews, and stories into teaching, learning, and research” (Arcand et al., n.d., p. 36).

Decolonization – requires leadership from non-Indigenous peoples. Non-Indigenous people created and currently maintain the system, which Métis, First Nation, and Inuit have difficulty influencing. The creators of the “divisive and demeaning actions, policies, programming, and frameworks” (Arcand et al., n.d., p. 36) must lead the change. Indigenous voice will collaborate on which changes will provide greatest impact.

Reconciliation – will require healing of relationships between Indigenous and non-Indigenous peoples. Leadership from non-Indigenous peoples will be advantageous for successful reconciliation, recognizing the impact of systemic policy on Indigenous people and who is responsible for those policies. Working in tandem with Indigenous community will be most beneficial. One reason for this comes from feedback received from Elders and Knowledge Holders. The absence of a consistent friendly relationship between the two groups is a reason for distrust of the process. Authentic reconciliation will reduce barriers and rebuild lost trust.

Engaging in any one of the three initiatives will begin to change the education landscape and improve relations. The greatest improvement will happen when we are engaged in all three components of the Venn diagram, the cross-section of Indigenization, decolonization, and reconciliation. Determining personal and systemic areas of strength and influence will help identify the starting point. Accomplishing the goal of IDR in education can happen by finding others who will compliment areas where you need additional support. Leading these efforts with hen la mimwayr (one mind) and hen keur (one heart) will produce meaningful results.

Pause for Thought

- How will I go about learning the names of the original inhabitants of the land on which I live?

Reflect on ways to build relationship with the Indigenous peoples of the land you are on. Are they identified in the original language or is the language thrust upon them? How will you go about learning the original names? - How will I go about finding Indigenous peoples in my subject area?

Reflect on ways to foster relationships with scholars in the field. How will I reduce barriers to collaboration? - How will I learn and unlearn the dual history of this land called Canada?

Reflect on how the dominant culture has told the history. What will I do to ensure that Indigenous voice is part of learning? - How will I work to build relationships with Indigenous peoples based on kindness, compassion, and understanding?

Reflect on steps that I can take to address the hurt and contribute to healing the relationships.

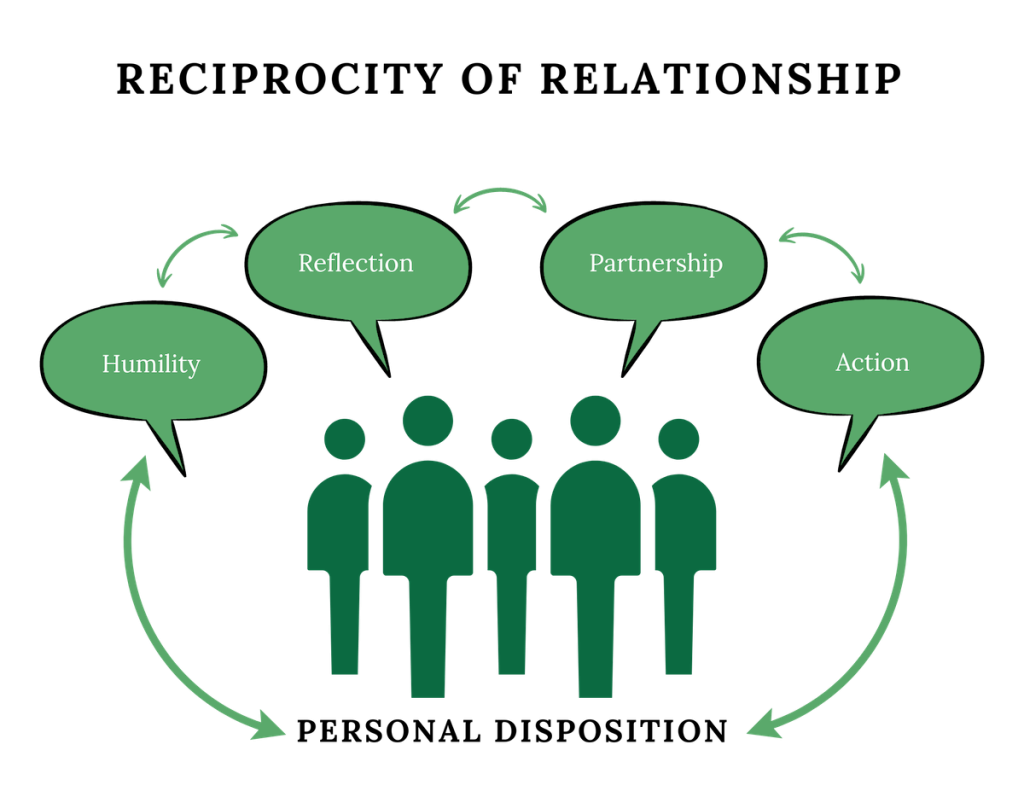

Reciprocity of Relationship

Understanding the reality experienced by First Nation, Inuit, and Métis individuals and communities is essential for knowing, valuing, and believing in learners. Continued involvement and dedication to improving teaching and learning aimed at enhancing the Indigenous student experience and improving achievement afforded me the opportunity to be creative. The result of the creativity is a model used to identify encouraging practice in support of learning titled, Reciprocity of Relationship. The model describes ways in which an educator can approach learning in partnership with the learners. Imperatives are the foundation for the Reciprocity of Relationship model and influence indicators to guide growth.

Historically, Métis, First Nation and Inuit learners have difficulty seeing themselves in an education system designed to assimilate Indigenous learners. Educators have a responsibility to work in partnership with First Nation, Inuit, and Métis to foster understanding of culture, language, and tradition to support improved outcomes for all learners (Ministry of Learning, 2018). Culturally, the current reality will shift when First Nation, Inuit, and Métis ways of knowing, being and doing stand in tandem with western paradigms. A partnership of learning forged between Métis, First Nation and Inuit and the non-Indigenous community is pivotal in supporting culturally responsive educator practice

The intended outcome of this model is to support all educators in developing a disposition of reciprocity through effective cultural responsiveness to change the current reality. All educators should strive to continually engage in learning that supports Reciprocity of Relationships.

A. Disposition

The Disposition Domain describes the critical, fundamental understanding of an educator’s mindset needed for the respectful approach to improving the educator-learner relationship, engagement and, in the end, achievement. There will be observable benefits for Indigenous learners when the dispositional domain position becomes the norm. Additionally, non-Indigenous learners can experience a shift in values, beliefs, and attitudes.

Educators have a responsibility to instruct all students about the history of the Inuit, Métis, and First Nations on this land called Canada. Providing all students with opportunities to gain experience about the historical and contemporary relationships between Canada, First Nations, Inuit, and Métis is an increasingly key component of citizenship education which helps reduce conflict, foster trust, and improve relationships (Ministry of Learning, 2018). Learning about our shared history by growing understanding within learners begins to reduce misconceptions that contribute to racism. Educators will adapt the curriculum, build partnerships, engage in shared decision-making, and ensure students achieve learning outcomes.

Approaching education with a mindset that promotes learning and unlearning about this land’s dual history builds comprehension for all students. This knowledge will help reduce misconceptions that contribute to racial ideals. Working together, we can foster trust and improve relationships, which is an essential component of citizenship education. Humility, reflection, partnership, and action will work together, they will nurture an inherent tendency to see, feel, think, and act in ways that nourish reconciliation. This work will take each member of the education community on a journey that will move education for First Nation, Inuit, and Métis.

| Personal Disposition Indicators | |

|

|

B. Humility

Indigenization, decolonization, and reconciliation in teaching requires an understanding of the Indigenous diversity present in the classroom, school, and community. A humble approach to education will involve the educator seeking ways to honour learner’s prior knowledge, protecting space for learner voice, and valuing participants through flattened hierarchies. The humbled educator accepts personal faults and is aware of personal biases that impact instruction, assessment, and expectations.

A humble educator will position themselves as a learner to think deeply and creatively about their practice. They will seek out opportunity to build authentic relationships with students of Indigenous ancestry. Through these relationships, a humble approach will reduce the hierarchy and provide gifts of learning to all. The humble educator will provide understanding that they can become the learner and the learner can become the educator. This reciprocal learning relationship will elevate Métis, First Nation, and Inuit knowledge to levels equivalent with Western knowledge.

An educator will demonstrate a humble disposition when they provide evidence of unlearning narratives that diminished Inuit, Métis, and First Nation ways of knowing, and doing. This will require a commitment by the educator to decolonize instruction, curriculum, and assessment. Working collaboratively with Indigenous education specialists will be a priority. Creating space that enables First Nation, Inuit, and Métis learners to retain their value systems is one of the goals of the model. An examination of personal beliefs by educators to reflect on the impact of bias on instruction, assessment, and learner expectations will support retention of those value systems.

| Humility Indicators | |

|

|

C. Reflection

Indigenization, decolonization, and reconciliation in teaching requires educators to reflect on their purpose in the classroom, school, and community in relationship to Métis, First Nation, and Inuit ways of knowing, being and doing. A reflective approach to teaching and learning will involve the educator recognizing unconscious bias and social positioning. The reflective educator consciously seeks to identify how lived experiences have influenced their worldview and recognize this may cause unnecessary difficulty for learners and caregivers. The reflective educator will question personal and systemic biases and assumptions.

The reflective educator will listen to the experiences of Inuit, Métis, and First Nation learners, caregivers and community and a commitment to seeking understanding. Approaching these lived experiences with a strengths-based attitude will counter act deficit thinking. Trust in learning will manifest as the reflective educator considers the impact the learning environment plays in the Indigenous student experience. Supporting physical, emotional, intellectual, and spiritual balance for everyone will create brave, safe learning spaces. As educators practice thoughtful reflection, authentic integration of First Nation, Inuit, and Métis culture, tradition, and knowledge becomes part of their teaching toolkit.

| Reflection Indicators | |

|

|

D. Partnership

Indigenization, decolonization, and reconciliation in teaching requires working in tandem with learners, caregivers, partners, and community. A partnership approach to education requires respecting multiple worldviews that will foster understanding of the value of shared responsibility. A relational educator takes a humble approach to engaging in partnership, recognizing formal and informal power structures favour the dominant culture. Understanding and exploring the Treaty relationship invites educators to reflect on personal and professional responsibilities to reconciliation and as stewards of the land. The result of a purposeful educational partnership is improved outcomes for Indigenous learners.

The educator working to build partnerships will strive for diversity to support improved outcomes for Métis, First Nation, and Inuit learner success and support for reconciliation. These partnerships will embrace the idea of shared responsibility for learning and learners. The partnerships will grow at the school and community level. The improvement of educational outcomes and an increased sense of empowerment will begin with a culture of collaboration.

| Partnership Indicators | |

|

|

E. Action

Indigenization, decolonization, and reconciliation in teaching requires the educator to respond to the inequities in their classroom, in the school, and in the community. An action-oriented approach to education will involve taking concrete steps to obtain equitable outcomes for all learners with a focus on the success of Inuit, Métis, and First Nation learners. The initiative-taking educator takes responsibility to influence change for and with people in all parts of their lives including the classroom. The initiative-taking educator makes the conscientious choice to overtly affirm Indigenous culture and to deconstruct and adjust practices that rely on Western ways of knowing, being and doing.

A commitment to action and shifting the system requires utilizing or applying a variety of evidence-based teaching practices that honour individual learners and Indigenous cultures. An invitation to First Nation, Inuit, and Métis learners to share culture in a brave, safe space is one example of wise practice. A brave, safe space can be a response to the historical imperative. Committing to inclusion of Métis, First Nation, and Inuit voice in learning begins to address the dual history narrative. An educator taking initiative for change will employ social justice practices. This will support healing through the development of learner confidence and pride in self.

| Action Indicators | |

|

|

F. Relationships – Miyeu wiichayhtoowuk

“You have to develop a relationship with Indigenous students. You can’t keep your distance. They want to know you; they want to connect with you. They need to have a sense of belonging.” (Goulet & Goulet, 2015, p. 105)

The Michif words for relationships (see above) highlight the importance of knowing and believing in one another. Moving forward together as partners in learning requires the creation of authentic, holistic relations. Lii vyeu (old people) share that the more we know about the stories and events that bring us to this day, the deeper the connection to learning we will have.

Reciprocity is a fundamental value in Inuit, Métis, and First Nation culture. Working to achieve respectful relations with Indigenous and non-Indigenous peoples benefits from the gifting and receiving of knowledge. Learning is a ceremony and when relationship between educator, learner, elders, and community results in authentic collaboration, change will happen.

Educators can strive to be inclusive of Indigenous knowledge to keep aligned with Métis, First Nation, and Inuit pedagogy. When Indigenous ways of knowing and doing become culturally relevant, all students can further respect the knowledge. Building authentic relationships will disrupt the idea that Inuit, Métis, and First Nation ways of knowing are secondary to the dominant culture. Since contact the dominant paradigm required First Nation, Inuit, and Métis to fit into the box created by the non-Indigenous.

A holistic approach to building relationships supports balance on all levels of ourselves. We are beings which need physical, emotional, intellectual, and spiritual balance to move forward. Having Elder, Knowledge Holders, and community engaged in the learning journey will provide avenues of support for maintaining balance. A First Nation, Inuit, and Métis perspective on education removes the compartmentalizing that learners may often experience with Western education. Indigenous Education is lifelong, connected to community, and integrates knowledge and personal growth.

Pause for Thought

- How does educator disposition impact learning?

Understanding the importance of relationships in learning, reflects on how educator disposition will advantage or disadvantage learning. What might the possible implications be for Indigenous and non-Indigenous learners? - Consider an educator’s position in teaching and learning, how can one create space for Métis, First Nation, and Inuit learners to retain their value system?

Reflect on barriers that work to assimilate Indigenous learners. What can an educator do, within their control, to change the system? - How do educators engage in personal reflection aimed at examining bias and privilege?

What support do educators require for seeking to cultivate brave, safe spaces of learning to promote mutual learning and building of trust? - How can an educator embrace the belief of shared responsibility for learning?

Reflect on how the education paradigm can shift to recognition that the educator can become the learner and the learner can become the educator. What steps must an educator take to affirm individual identity and co-construction of curriculum, instruction, and assessment?

E. Applying the Knowledge (Curriculum, Instruction, & Assessment)

Educators have a responsibility for embedding IDR in all areas of teaching and learning. As mentioned earlier, when presented with the reality lived by First Nation, Inuit, and Métis learners, educators have a moral obligation to affect change. We can no longer maintain the status quo and hope that the situation resolves itself and learning becomes equitable for all. Alexander Den Heijer said it best, “When a flower doesn’t bloom you fix the environment in which it grows, not the flower.” For too long the responsibility to change outcomes for Métis, First Nation, and Inuit have been the responsibility of the learner and their families. The time has come to challenge education institutions (environment) to explore opportunities for change in policy and procedure and support learning for Inuit, Métis, and First Nation.

An understanding of the position First Nation, Inuit, and Métis experience daily will support the work moving forward.

- First, we must acknowledge that the current reality is historical and persistent.

- This reality was here when we arrived and given that we inherited this reality, responding to it is everyone’s responsibility.

- Second, if we are to change this reality for Métis, First Nation, and Inuit we must examine our own values, beliefs, and behaviors in relation to institutional policies and practices.

- Third, we can have influence if we hear from our First Nation, Inuit and Métis and listen to what they need.

- Fourth, Hon. Senator Murray Sinclair eloquently stated on December 13, 2013, “Education has gotten us into this mess, and education will get us out.”

Curriculum Renewal

Trusting that educators have a disposition of reciprocity in place, curriculum renewal will be an effective starting place. Given that Indigenous knowledge has been present since time immemorial, authentic inclusion can across a multitude of curriculum is possible. Working in tandem with Elders, Knowledge Holders, and lii vyeu (old people) will ensure authenticity of the knowledge and affirm ways of knowing for the non-Indigenous student population.

Creating a balance between historical and contemporary knowledge is central to overcoming barriers. Too often educators rely on the past when advocating for Indigenous knowledge. This will reduce opportunities for growing understanding of an Indigenous response to current issues. As Métis, First Nation, and Inuit we are still here, we are knowledgeable, and we are striving to thrive.

Curriculum writers can begin with an analysis of current curriculum for content and voice. When the analysis is complete, and the curriculum writer appreciates the imperative to move forward, working in partnership with local organizations, tribal councils, and/or Métis/Michif Locals, can initiate the journey.

Instruction Enhancement

Predominant instruction strategies model Western tradition and history. Often, educators will instruct in a way they experienced, largely because it worked for them. When learners see themselves in curriculum, instruction, and assessment, they are more likely to achieve learning outcomes. The common instructional strategies used across education can improve outcomes for Inuit, Métis, and First Nation learners when enhanced with Indigenous pedagogy. This does not mean that Indigenous learners cannot succeed in the current traditional system. There are stories of success from across this land, sharing the story about the challenges faced to achieve success is of utmost importance. The realization is that more students could experience success when the principles of equity, diversity, and inclusion (EDI) are part of instruction. According to Statistics Canada in the 2021 census, 49.2 percent of Indigenous respondents reported having completed a postsecondary certificate, degree, or diploma (Melvin, 2023).

At the heart of Indigenous knowledge and instruction is authentic educator-learner relationships. Knowledge of the learner’s story they bring with them to the learning space will provide the educator the opportunity to choose EDI strategies that support learner needs. First Nation, Inuit, and Métis learners can arrive at places of learning with the weight of the colonial history impacting their experience. The weight of this history will manifest itself in diverse ways depending on access to support services prior to and during the higher education experience.

Ownership of the learning is beneficial to Indigenous students and will support all learners (Alberta Education 2005). When a learner understands the learning journey, personal investment in the outcomes increases. An educator can position themselves as a partner who will facilitate the learning. Instructional strategies that build independence have increased engagement and motivation for Métis, First Nation, and Inuit learners. Examples include independent study, cooperative learning, service learning, and experiential learning. Each of these will engage learners with diversity of instruction and foster independence.

Educators can enhance instruction when they take a holistic approach to teaching and learning. This approach will support maintaining balance physically, emotionally, intellectually, and spiritually. The humble educator will seek guidance from elders and knowledge holders to understand each of these components. Recognition of the impact balance has on learning from an Indigenous lens will validate Inuit, Métis, and First Nation worldview. Jacobs (2013) drew attention to eight guiding principles of learning that follow holistic principles and will assist Indigenous learners.

- “Allow for ample observation and imitation rather than verbal instruction. Also allow students to take their time before attempting a task so the chances for success are higher on the first effort.

- Make the group more important than the individual as often as possible in terms of both the learning process and learning goals.

- Emphasize cooperation versus competition whenever possible.

- Make learning holistic rather than sequential and analytic. Spend more time in dialogue talking about the big picture associations before looking at details.

- Use imagery as often as possible. Einstein wrote that “’imagination is more powerful than knowledge,”’ and Indigenous education takes advantage of this fact.

- Make learning connect to meaningful contexts and real life.

- Be willing to allow spontaneous learning opportunities to change pre-planned lessons.

- De-emphasize letter grading and standardized evaluations and use authentic narrative assessments that emphasize what is actually working best and what needs more work.” (Jacobs, 2013, pp. 70-71).

When using these guiding principles, it is important to maintain the holistic view and avoid seeing this as a checklist that will accomplish the goal of supporting First Nation, Inuit, and Métis learning and achievement. Educators who can find a starting place based on comfort and current knowledge of the principles will support learners. Indigenization and instruction provide educators with guidance to chart the course in their instruction. The starting point will be determined by educator disposition. Reflecting on learning outcomes, diversity of learners, and personal understanding of Indigenous pedagogy will aid in decision making.

Enriching Assessment

As mentioned previously, curriculum and instruction embody Western tradition. Assessment follows this pattern and can take advantage of implementation of Indigenous pedagogy. Educators willing to explore a diversity of assessment strategies and provide voice and choice for learners are following Indigenous ways of knowing and doing. Indigenous pedagogy and assessment for learning share common criteria. Timely, responsive feedback used to guide the learning are the foundation of Indigenous learning. The fFeedback can take a variety of forms and educators and learners can be involved in the writing. Low-risk, high-reward learning will motivate learners and grow independence.

Métis, First Nation, and Inuit culture brings variables to assessment that may not be present with all other learners. Assessment can be mindful of the existence of colonization and the impact on Inuit, Métis, and First Nation learners. Working together can raise awareness of systemic barriers in education for Indigenous learners and offer solutions. First Nation, Inuit, and Métis advocate for maintaining rigor in higher education while recognizing the impact colonization has on their learning. Indigenous leaders advocate for maintaining standards to enhance the learning experience of Métis, First Nation, and Inuit learners, while also acknowledging the necessity of providing appropriate support and intervention throughout their educational journey.

The support will take a variety of forms and will support all learners. An examination of Western traditional practices such as solid deadlines with penalties for missed due dates, no opportunity for second chances, or participation marks, provide an opportunity to reflect on purpose. This is often an assessment of behaviour and not directly connected to learning outcomes. On occasions where due dates are impacting the learning, educators and learners should engage in conversation that will shed light on the reasons for the delay and collaborate on solutions. Too often educator mindset explains these occurrences by articulating that “Indigenous learners don’t have the discipline needed for higher education.” This default position is disruptive and overlooks the impact of colonization on Inuit, Métis, and First Nation learners.

A diversity of assessment tools will likewise increase Indigenous learner achievement. Recognizing the diversity of learners supports the use of multiple assessment methods. Learners will increase success opportunities when presented with various methods used to express their knowledge. Assessment can take multiple forms connecting learning outcomes and knowledge evaluation. Mediums such as artwork, photo stories, reflective learning logs illustrate learners meeting course outcomes when used appropriately. This does not require educators to engage in wholesale assessment practice reform. A diversity of assessment used across the course will provide all learners the chance to illustrate their competency with outcomes.

Pause for Thought

- Reflect on the statement by Alexander Den Heijer, “When a flower doesn’t bloom, you fix the environment in which it grows, not the flower.”

How can you relate this metaphor to the educational challenges faced by Indigenous learners? Consider how changing the educational environment could impact these learners differently than trying to change the learners themselves. - Consider the importance of listening and learning in relation to Indigenous pedagogy.

Reflect on your own educational or professional practices. How can you incorporate more inclusive strategies that genuinely listen to and reflect the voices and needs of Indigenous learners? - Reflect on the compelling reasons for inclusion of Indigenous knowledge and perspectives in curriculum, instruction, and assessment.

How can you contribute to or advocate for the inclusion of Indigenous knowledge and perspectives within your curriculum? What steps can you take to ensure this inclusion is respectful and authentic? - Highlight the enrichment of assessment strategies by embracing Indigenous pedagogy to provide more equitable and responsive education.

Reflect on the current assessment practices you are familiar with. How can they be adapted or expanded to include diverse, low-risk, high-reward approaches that honour Indigenous ways of knowing and learning? What obstacles could educators face when implementing changes to assessments, and what strategies can be employed to overcome them?

Summary

This chapter outlines compelling reasons for engaging in IDR and shares thoughtful strategies for accomplishing the goal. IDR may seem daunting in a time of increased pressure on higher education. Respectful relationship and advocation for IDR at all levels of education leadership will increase the opportunity for success. Everyone invested in education shares in the responsibility for completing the journey.

The time has come to realize the value of IDR in education. Moving from words that highlight strategic thinking in planning documents to actions witnessed in learning spaces will be a challenge. Committing to the actions is the first step. A choice to enhance current practice with humility, reflection, partnership, or action will begin to spread the ripples of change. As First Nation, Inuit, and Métis learners begin to achieve equity in education, understanding the imperatives for Indigenization provides motivation to see the work succeed. Education can take the lead on reconciling the relationship between Indigenous community and higher education.

Embracing the philosophy of the Reciprocity of Relationship model can be the springboard for creative change to inclusive curriculum, instruction, and assessment. Adopting a humble disposition can enhance educator-learner relationships with the goal of improved teaching and learning. Trusting the process of IDR can maintain balance in learning spaces and support all students. When educators commit to support for Indigenous student success, healing can begin.

Indigenous and Western based pedagogy can co-exist. The learning spaces will benefit greatly when IDR becomes embedded in education. Indigenous and non-Indigenous learners, educators, and community can work together to make inclusion of Indigenous ways of knowing and doing a reality. Working together will impact curriculum, instruction, and assessment, and commit to reconciliation.

Final Thoughts

- How can educators navigate the complexities of incorporating Indigenous worldviews, knowledge, and perspectives into post-secondary education while fostering mutually respectful relationships between Indigenous and non-Indigenous peoples?

What must educators accomplish personally and professionally to build authentic, healthy relationships? - Reflect on the imperatives outlined for engaging in Indigenization, decolonization, and reconciliation (IDR) in education.

Which imperative resonates with you the most personally or professionally, and why? Consider how your understanding of this imperative might influence your approach to incorporating Indigenous perspectives and practices into your teaching or educational institution. - Reflect on the complex interplay between IDR within the context of education renewal. Consider how diverse groups, including Indigenous peoples, non-Indigenous educators, and community leaders, contribute to each component of IDR.

How can strategic leadership from diverse stakeholders help reduce barriers to implementation and foster authentic engagement in creating a more inclusive and equitable education system? - Reflect on the role of educators in embedding IDR into all aspects of teaching and learning. How can curriculum renewal, instruction enhancement, and enriching assessment practices align with Indigenous pedagogy and values, while also acknowledging and addressing the systemic barriers faced by Métis, First Nation, and Inuit learners?

Consider how incorporating Indigenous ways of knowing and doing can promote equity, diversity, and inclusion in educational practices, fostering greater learner engagement and success.

References

Alberta Education. (2005a). Our words, Our Ways: Teaching First Nations, Métis, and Inuit learners. ERIC. https://eric.ed.gov/?id=ED491527

Arcand, E., Arcand, L., Badger, B., Battiste, M., Blair-Dreaver Johnston, A., Buffalo, M., Campbell, M., Creely-Johns, M., Cummings, N., Duquette, R., Fleury, N., Halfe, L., Hamilton, M., Henderson, M., Kayseas, F., Kayseas, E., Keewatin, M., Lewis, K., Linklater, L. J., … Tsannie-Burseth, R. (n.d.). ohpahotân | oohpaahotaan. University of Saskatchewan. https://indigenous.usask.ca/documents/lets-fly-up-together.pdf

Bartlett, C., Marshall, M., & Marshall, A. (2012). Two-eyed seeing and other lessons learned within a co-learning journey of bringing together Indigenous and mainstream knowledges and ways of knowing. Journal of Environmental Studies and Sciences, 2(4), 331–340. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13412-012-0086-8

Chrona, J. (2022). Wayi Wah! Indigenous pedagogies: An act for reconciliation and anti-racist education. Portage & Main Press.

Goulet, L. M. & Goulet, K. N. (2015). Teaching each other: Nehinuw concepts and indigenous pedagogies. University of British Columbia Pess.

Howe, E. (2013, November). Bridging the Aboriginal Education Gap in Saskatchewan. Gabriel Dumont Institute. https://gdins.org/me/uploads/2013/11/GDI.HoweReport.2011.pdf

Jacobs, D. T. (2013). Teaching truly: A curriculum to indigenize mainstream education. Peter Lang.

Joseph, B. (2018, August 16). What reconciliation is and what it is not. Indigenous Corporate Training Inc. https://www.ictinc.ca/blog/what-reconciliation-is-and-what-it-is-not.

Joseph, B. (2020, February 24). A brief definition of decolonization and Indigenization. Indigenous Corporate Training Inc. https://www.ictinc.ca/blog/a-brief-definition-of-decolonization-and-indigenization.

Louie, D. W., Poitras-Pratt, Y., Hanson, A. J., & Ottmann, J. (2017). Applying indigenizing principles of decolonizing methodologies in university classrooms. Canadian Journal of Higher Education, 47(3), 16–33. https://doi.org/10.47678/cjhe.v47i3.187948

Melvin, A. (2023, October 27). This study uses data from the 2021 census to report on postsecondary educational attainment and labour market outcomes among Indigenous adults aged 25 to 64 years. Postsecondary educational attainment and labour market outcomes among Indigenous peoples in Canada, findings from the 2021 Census. https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/pub/75-006-x/2023001/article/00012-eng.htm

Ministry of Learning. (2018, June). Inspiring Success: First Nations and Metis PreK-12 Education Policy Framework. Regina, Government of Saskatchewan.

Simes, J. (2023, June 18). Indigenous educators in Saskatchewan look to boost graduation rates. Saskatoon Star Phoenix.

How to Cite

Isbister, D. (2024). Indigenization and the future of post-secondary education. In M. E. Norris and S. M. Smith (Eds.), Leading the Way: Envisioning the Future of Higher Education. Kingston, ON: Queen’s University, eCampus Ontario. Licensed under CC BY-NC 4.0. Retrieved from https://ecampusontario.pressbooks.pub/futureofhighereducation/chapter/indigenization/

This work is licensed under CC BY-NC 4.0. To view a copy of this license, visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/