Malcolm Butler

Financing Canadian Colleges and Universities in the 21st Century

Malcolm Butler

Saint Mary’s University

Introduction

I have spent 16 years in academic administration, first as a Dean of Science at Saint Mary’s University (4 years), then Dean of Science at Carleton University (7 years), and finally a return to Saint Mary’s as Vice-President Academic and Research (5 years). Each role and institution gave me a different perspective on issues around university finance, through both good times and bad. As Dean, I was working in Faculties that were growing and thriving – and where there were means to invest to support that growth. As Vice-President, I worked through COVID, which was a time of crisis for all universities, including mine, with impacts persisting to this day. Each role and institution facilitated contacts with other colleagues, near and far, with whom these perspectives could be discussed and evolved. I was privileged to work with a number of senior leaders, faculty and staff who all cared passionately about their work and helping their university succeed. Now, nearly two years out of administration with time to reflect, this chapter is shaped by my experiences and perspectives, along with ongoing readings, on university finances and the insights shared by those exceptional colleagues.

Overview: Arriving at the current state

Universities in Canada underwent explosive expansion and growth in the last century, evolving from institutions with strong ties to various religious denominations to largely secular government-supported institutions. Access became a mantra, but with access came expense that, in the early stages, governments were willing to provide support for. This support helped develop a university system (even in the absence of inter-provincial collaboration) where the standard of education is strong across the country, whether a student is attending a large or small university. That standard still exists and should be a source of pride.

In the latter half of the last century, cracks began to appear in that support. As governments struggled with large deficits themselves and (at times) exceedingly high interest costs on those deficits, they looked to cut back – and universities were a relatively easy target. For those interested, there are a number of books that look back over these times, for example “Growth and Governance at Canadian Universities – An Insider’s View” by Howard Clark (Clarke, 2003) My first direct observation of this was in the 90’s and it is clear in hindsight that actions then represented the start down the path to the current predicament.

In the early part of this century, funding was definitely more constrained. Provincial grants were largely fixed with modest (often less than inflation) increases provided each year or, at best, per-student funding was held fixed. In this environment, universities turned to enrolment growth to fill in the gaps. Class sizes grew, and where increased numbers of courses or sections were required, part-time/sessional faculty were hired in increasing numbers to fill the gaps. Concerns began to be raised about the impact of these actions on both the standard of education and those hired in these sessional roles – this was happening across the country at virtually every university. Further, the trend to growing international enrolments began. Originally, international tuition fees were largely calibrated to the “true” cost – roughly the equivalent of (tuition+grant)/student. This changed.

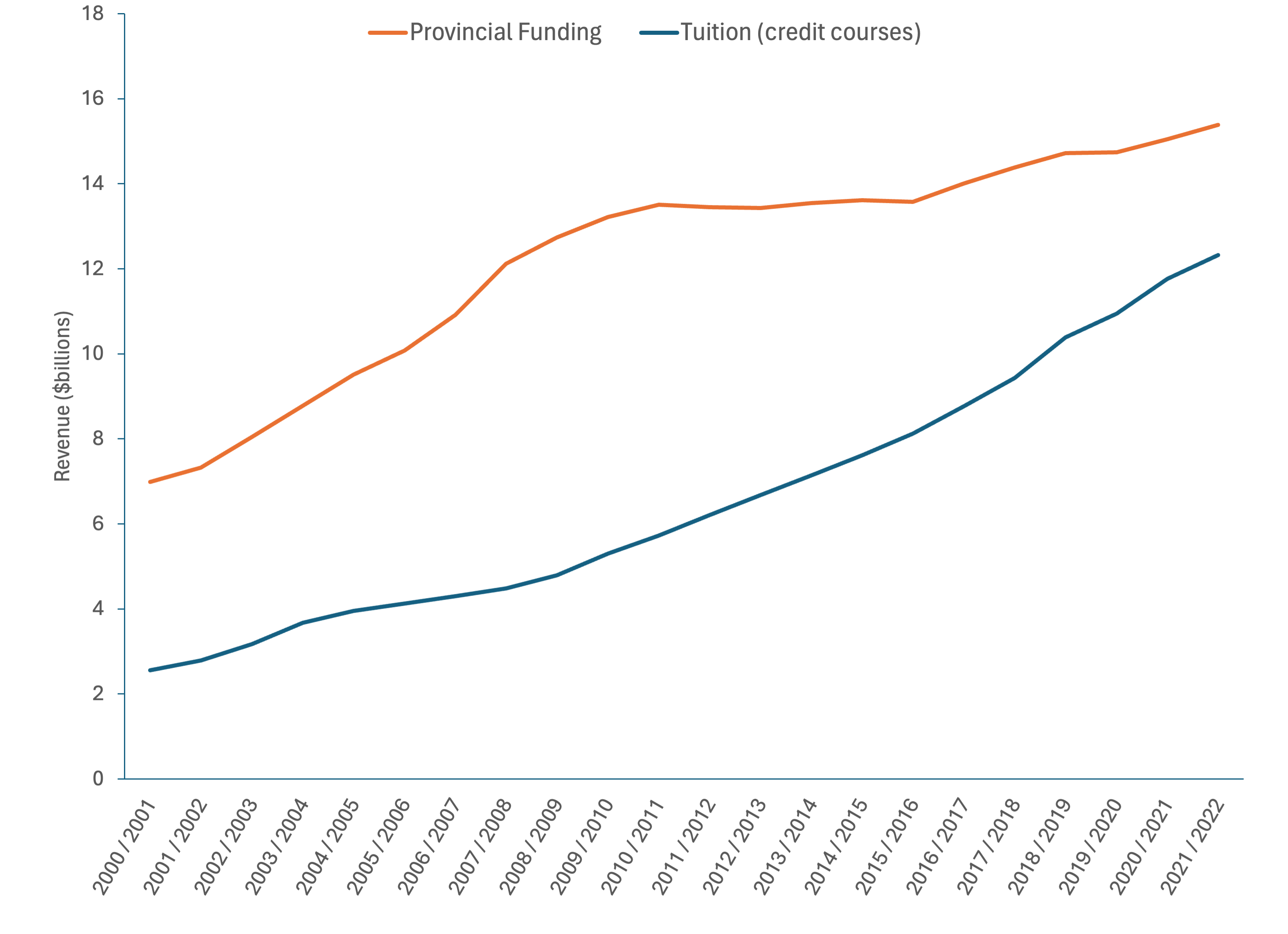

Statistics Canada provides a comprehensive snapshot of funding sources to universities back to 2000/2001 (Statistics Canada, 2023b). We won’t analyze those all in great deal here but will note that it is interesting and eye-opening to review the broader picture with time. In Figure 1, we see a comparator of revenue from (for credit) tuition fees and provincial funding in current dollars. There are other sources of operating funds, but they are relatively minor contributions relative to these two. Donations are also interesting to look at, but they rarely offset operational costs.

Figure 1

Note. Comparison of revenue from Provincial sources and credit-based tuition from 2000-2022. Source: Statistics Canada (2023b).

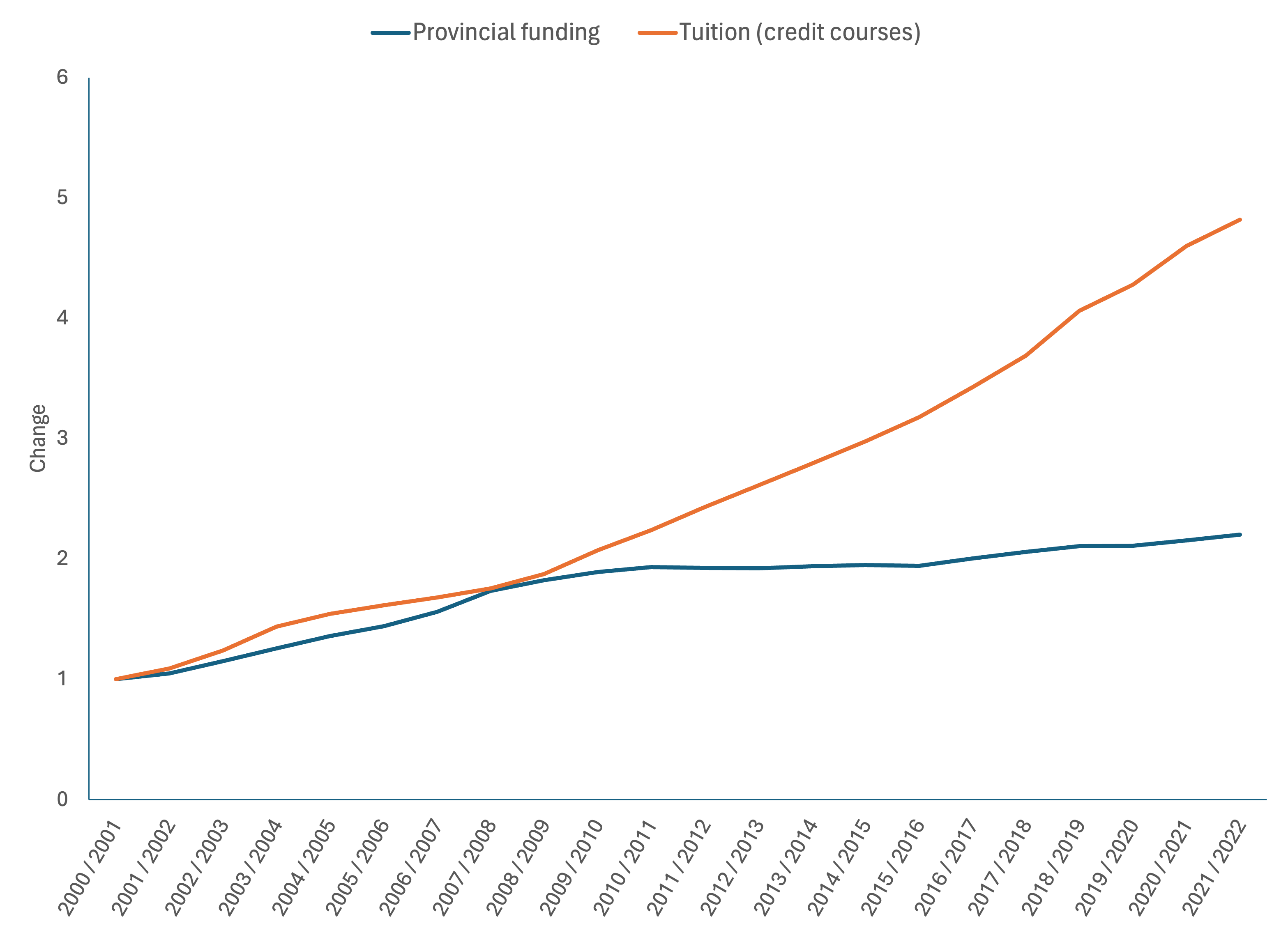

We can see from Figure 1 that there is a steady growth in tuition income throughout the time period shown. Government funding fluctuates, but the growth slows down starting around 2008/09. This becomes clearer when we plot the data using 2000/2001 as a baseline. In Figure 2, you see the trend diverging sharply. Tuition fees are clearly making up a greater fraction of revenue, particularly after 2008. Not only do tuition revenues rise sharply after this point in time, but provincial funding is also virtually flat in current dollars. As we move to the present, the funding model profile looks less and less like a public institution and more like what one sees in the U.S. at private institutions with government subsidy for student aid (Pell grants) – but without the capacity to raise absolute value of and revenue from tuition fees to a level that would be required to fully support the academic missions. This growing disparity helped set the stage for problems universities in Canada are now facing around their finances.

Figure 2

Note. Comparison of the change in revenue Provincial sources and credit-based tuition using 2000/2001 as a baseline. Source: Statistics Canada (2023b).

In 2020, COVID changed everything, not just in Canada but globally. The chaos we all experienced in the spring of 2020 has left a mark on the system and we have not recovered, and things will certainly never be the same as they were pre-pandemic (those universities with connections and partner programs in China felt the effects earlier, but largely did not appreciate what this foreshadowed). The most significant impact on university finances was the dramatic drop in international student registrations. The federal government did step in here to help where it could, allowing international students to continue or commence their studies online while still retaining eligibility for the post-graduate work permit (a major draw for international students to Canada) – but the time zone differences, the fact that universities were not really prepared to offer the sophisticated hybrid and/or asynchronous online courses at scale that would have best supported these students, and growing post-secondary capacity in the home countries of these international students all contributed to a decline in international enrolments at many institutions – a decline that most institutions still see today. Some have rebounded to an extent, but certainly not all. The federal government is now taking actions that will exacerbate this, restricting visa access due to explosive growth in numbers pre-COVID and post-COVID at a relatively small number of institutions. This past year has seen constant reporting of large deficits across the country, reserves being exhausted, and layoffs are underway – nearly all laying the blame on declining international enrolments. This coming fiscal year will prove challenging for even more institutions with the new restrictions, further compounded by some provincial governments to tighten funding or tuition controls in such a way that will impact enrolment and overall finances. We all struggle now to understand what the next decade will bring.

International Students and University Finances

In earlier times, international fees were set in a spirit of reflecting the “true” cost of their education compared to the subsidized cost for a domestic student. A growth in an appreciation of internationalization and intercultural learning saw these students as bringing intellectual benefits to the university. They would bring different perspectives and backgrounds to the discussion and, should they return home, take with them a deeper understanding of Canada. Most universities still seek this ideal but face increased difficulty in maintaining it as finances are ever more constrained.

Many things influenced the shift in focus on international student recruitment. One was the realization that there were cohorts of international students seeking advanced post-graduate professional degrees, particularly in business and engineering, and thus there was a growth in targeted programming. These “full-cost” programs spread across the country in the 2000’s. Tuitions became driven by the revenue generating opportunities these programs presented, revenue that could in turn support or subsidize other initiatives at the universities. While these revenues are welcome, they are still a relatively small fraction of the overall tuition revenue – which is still dominated by undergraduate student enrolments. International tuition fees for all programs also started increasing alongside these new “full-cost” initiatives, particularly as governments started capping tuition fee increases for domestic students. Many universities introduced dramatic increases to international tuition fees – particularly in undergraduate programs popular with international students, such as business and engineering. Tuition ratios that were once of order 2:1 (international:domestic tuition) became much larger across the country. With that, international tuition fees inevitably became a larger fraction of university revenues with many aspects of the university’s operations increasingly dependent on them.

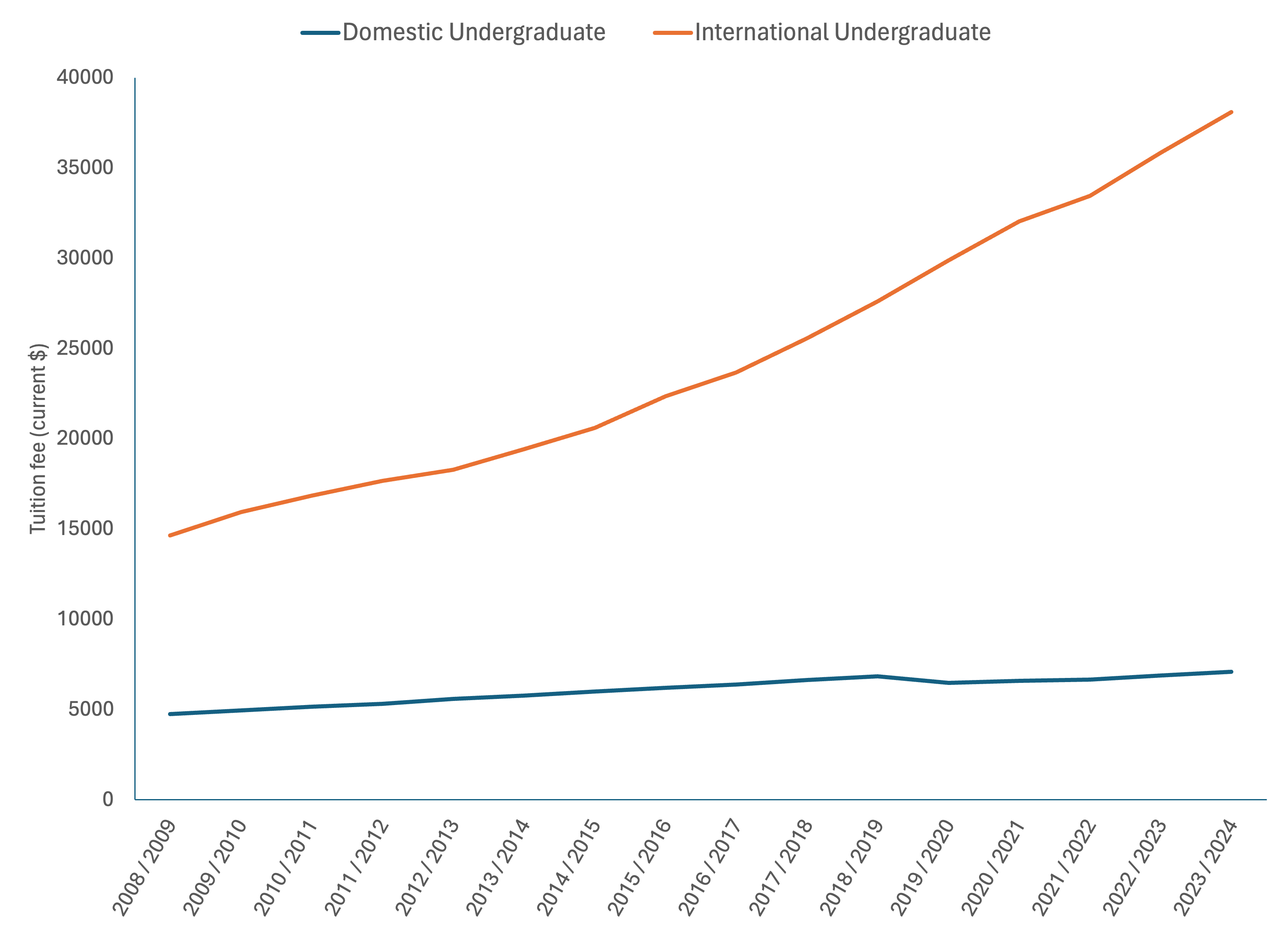

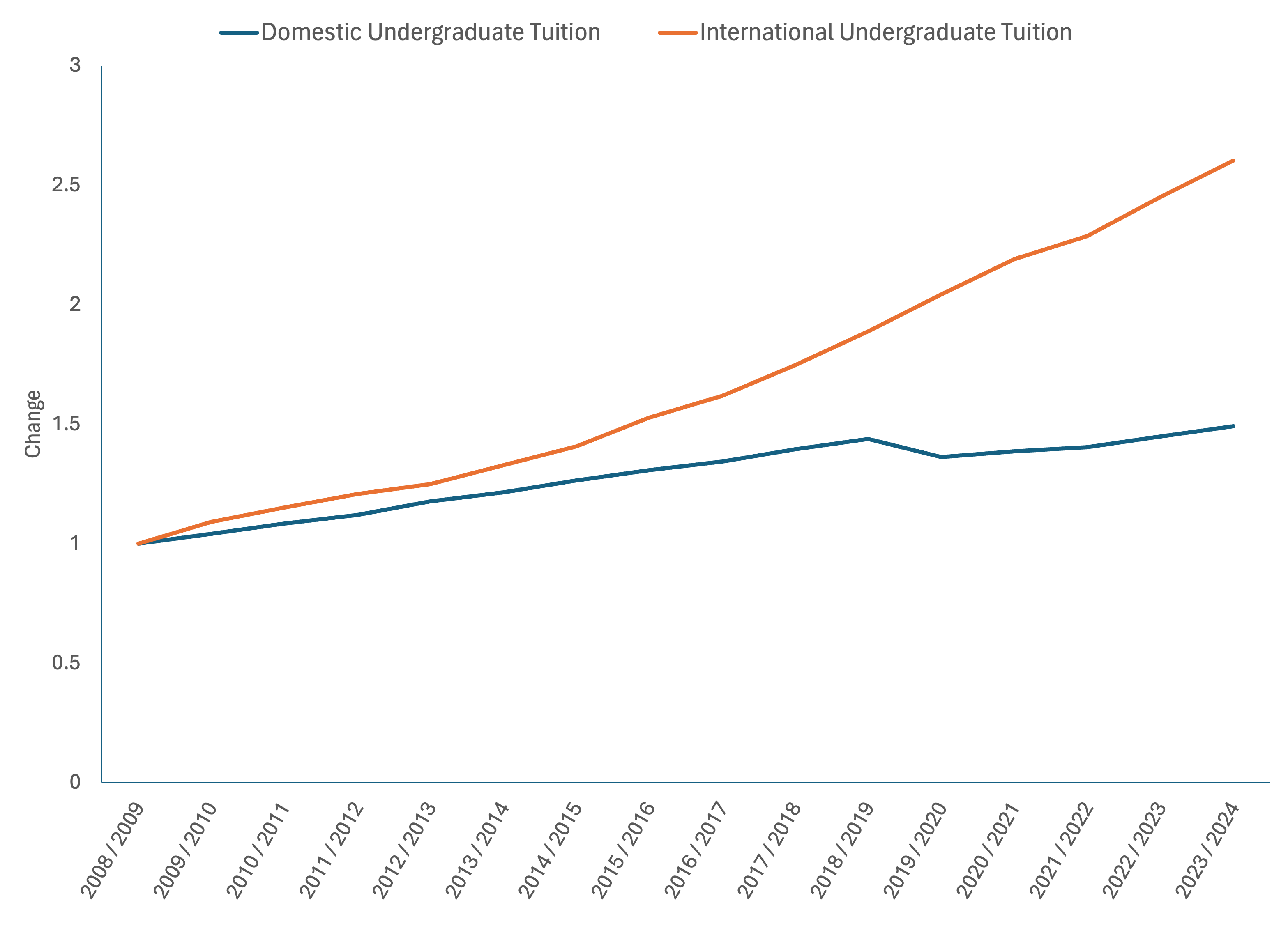

Using further data from Statistics Canada (2023c), Figure 3 illustrates the changing tuition costs in current dollars, domestic vs. international, over time – a national average – from 2008/09 onwards (note that was the year when tuition and provincial grant revenue increases started diverging rapidly). Here we see universities driving large increases in international tuition fees to offset relatively flat growth in domestic tuition fees. Figure 4 illustrates this further, also using 2008/09 as a reference point. We can see that domestic tuition fees grew by approximately 50% by 2021/22 over 2008/09. International fees, in that same time period, grew by approximately 160% in that same time period. Of course, these ratios vary wildly by program and even by province. For example, in 2021/2022 the Maritime provinces still had ratios of international tuition fees to domestic tuition fees that are of order 2-2.7:1. Québec had the highest ratio in 2021/2022 – over 9:1. That will be changing now as the Québec provincial government has imposed changes in out-of-province domestic fees for the English-language universities. However they might vary, they are all reflective of a trend to extract more revenue from international students, where universities were free from constraints imposed by their provincial governments for domestic students.

Figure 3

Note. Average tuition fees, domestic vs. international, in Canada from 2008-2022. Note the steep increase seen in international fees in this period. Source: Statistics Canada (2023c).

Figure 4

Note. Highlighting the change in domestic vs. international tuition fees from 2008-2024. Unconstrained by government policy, international fees have more than doubled in current dollars. Source: Statistics Canada (2023c).

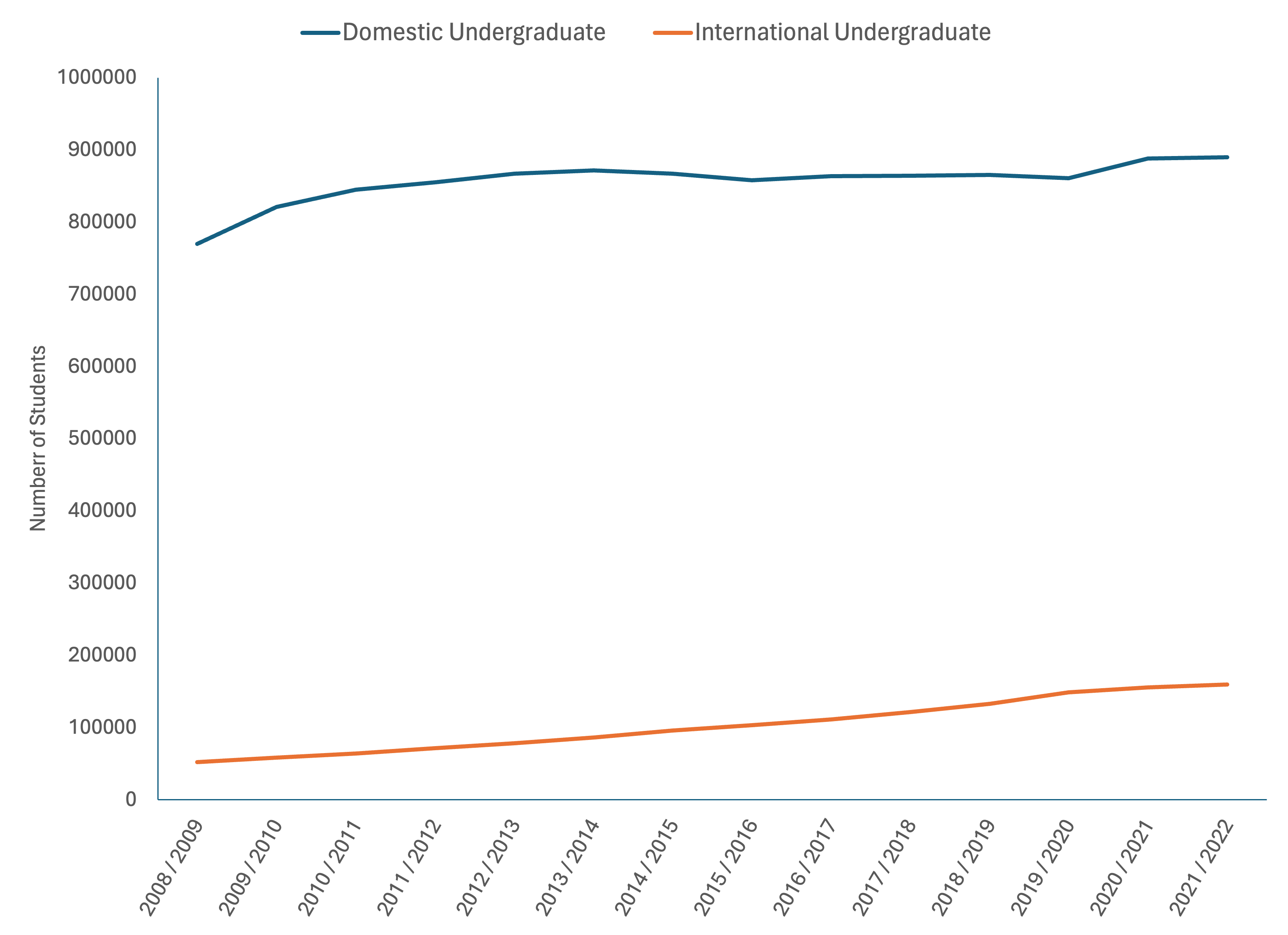

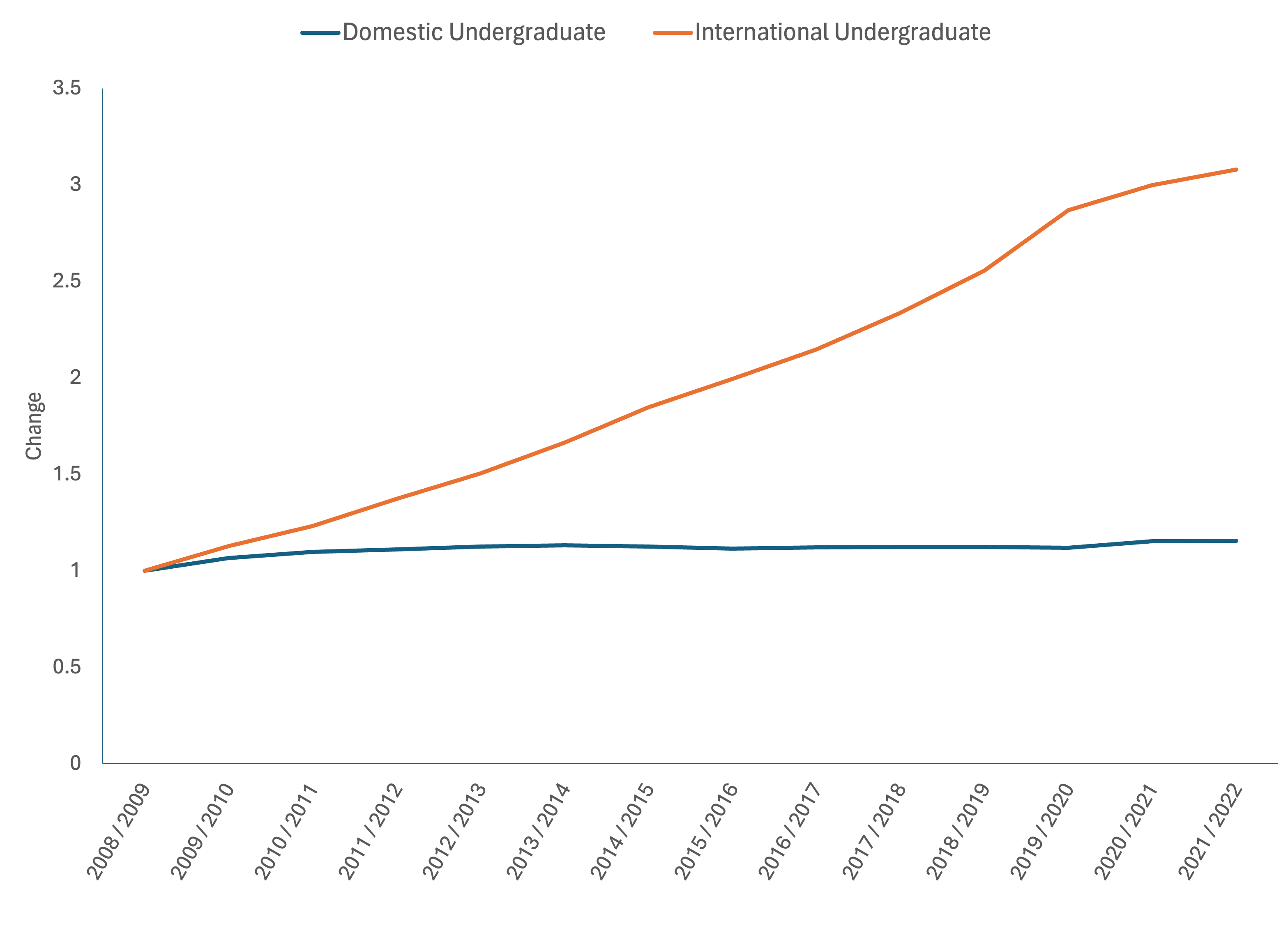

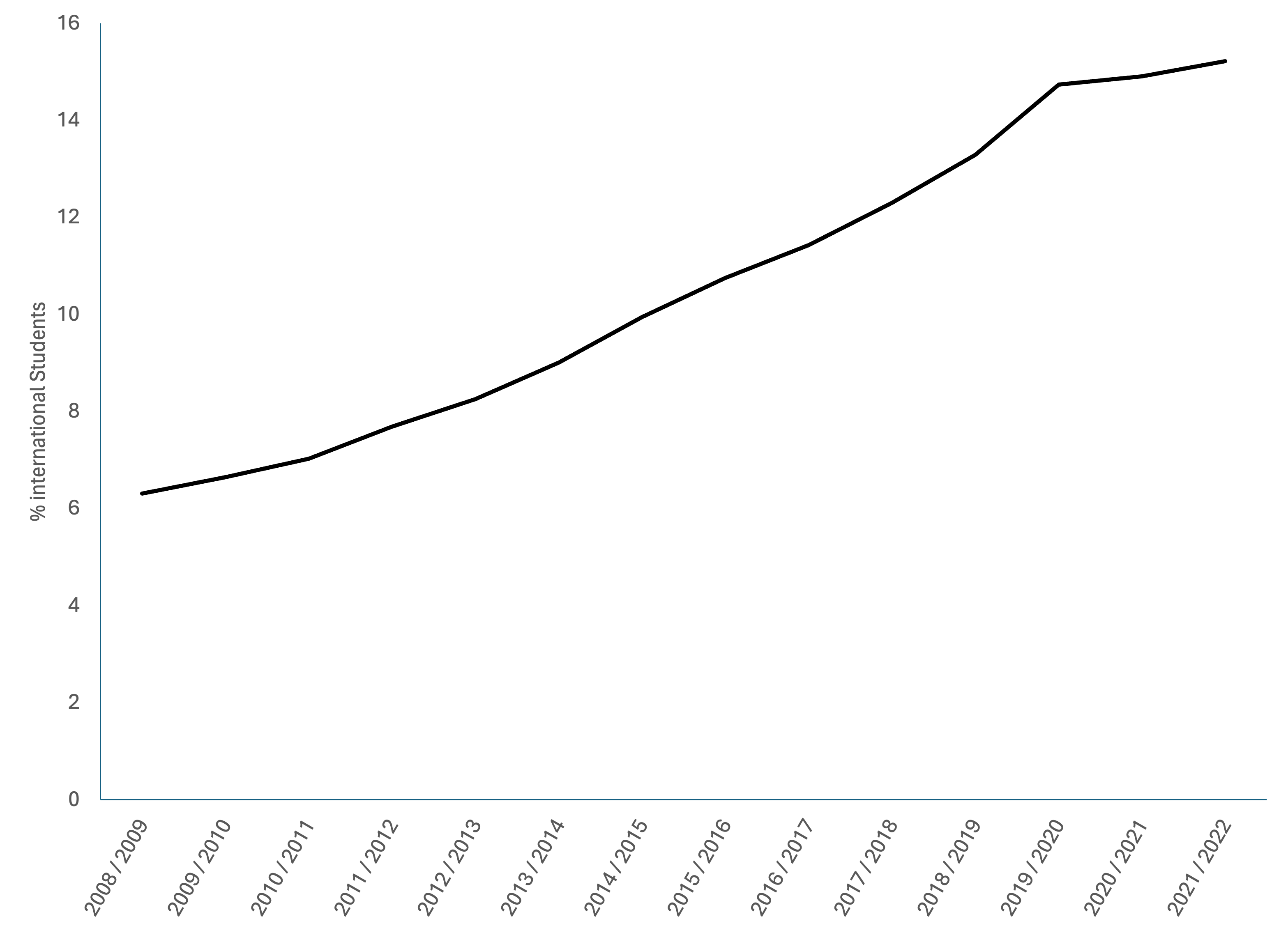

We can compare this to student enrolments over the same time period – where we see dramatic growth in international students, particularly as a fraction of university populations. In Figure 5, Statistics Canada (2023a) data from 2008/09 to 2021/22 is shown for enrolments in bachelor’s degree programs at Canadian universities. This is the common tuition revenue generator for universities, large and small, and is usually the backbone of their tuition revenue. Figure 6 shows the relative change in enrolments during the same time period. You can see steady growth in international student enrolment, but that it plateaued in 2020/2021 – the onset of COVID. The continual increases that universities were relying on in their budgets vanished. This has continued post-COVID and, as it was noted earlier, the federal government has taken action to further reduce the number of international students studying in Canada at the undergraduate/diploma level. This has led to a spotlight on international students in Canada that has been in the news these past few months, creating challenges for recruiters in both logistics and perception of Canada as an attractive destination for international students. How these restrictions on international student visas are applied varies by and within provinces. The timing has been challenging relative to the international recruitment cycle, and we are likely to see further negative budget impacts on universities in this new fiscal year. Nonetheless, international students are a much larger fraction of university enrolment than they were pre-COVID (Figure 7), and they have changed universities in Canada in many positive ways. It will be a significant loss for all if a reduction in international student enrolment reduces opportunities for intercultural learning and cross-cultural communications in an ever-smaller global society.

Figure 5

Note. Domestic vs International undergraduate enrolments at Canadian universities from 2008-2022. Source: Statistics Canada (2023a).

Figure 6

Note. Relative change in domestic vs. international enrolment in Canadian universities from 2008-2022, with 2008 as a baseline. Source: Statistics Canada (2023a).

Figure 7

Note. International students as a percentage of the undergraduate population at Canadian universities from 2008-2022. Source: Statistics Canada (2023a).

International Context

Canada is not alone in facing financial challenges in the sector. Since the spring of 2020, one can hardly open a U.S. higher education new source without reading about another bankruptcy or university in deep budgetary crisis, with either bankruptcy, major reorganization, or even declarations of financial exigency. A recent opinion piece in Inside Higher Ed (Nietzel & Ambrose, 2024) outlines many of the universities, large and small, that had budget crises in 2023. The authors review responses and provide their own thoughts on how universities should be addressing their budget challenges. Universities in the U.K. (PwC, 2024) and Australia (Ross, 2024) are both seeing their governments looking to reduce and restrict international student visas similar to Canada’s actions – with the same concerns about impact on university finances being expressed by their leadership. The U.K. and Australia already have a higher level of political influence and control over university operations, and the funding of specific programming, so have already felt the impacts of government policy and priority shifts. International student enrolments may be the next policy shift and would have similar or even greater impacts on finances to what we are seeing here in Canada.

The other challenge Canada faces is the emergence of other competitive players in the post-secondary sector in countries that were previously sources of international students – China in particular. China has seen massive growth in university capacity, even pre- COVID (British Council, 2015) and more key institutions are placing higher in global rankings (Jack, 2023). China is working to be a destination country for international students, particularly from countries where it already has close ties – but also others.

What can be done?

Universities are very conservative, by and large – and sometimes smaller universities more so than larger ones. Change is hard, and slow, but something needs to be done. There have been experiments with other models – Quest University in Canada, for example, bucked the normal Canadian model, including through course delivery in blocks – where students take a single course at a time but ultimately has failed (Kozelj, 2023) (though not for reasons directly related to education and attractiveness for students). Arizona State University in the U.S. is frequently heralded as an institution embracing radical change, including changing how its academic units are organized to be around grand challenges, rather than disciplines, and embracing access for all with a meaningful emphasis on learning, and more. It is useful to review their website and see how they present their “Enterprise” model for academics and research (www.asu.edu) – and is interesting to watch how this effort continues to evolve but with a caution that many aspects may not be reproducible for all.

Post-COVID, the expectation was that university education would never be the same. Students would want online education and some larger institutions mused publicly that students wouldn’t bother with smaller institutions anymore if they could live at home and get a degree online from a more “prestigious” institution vs. a smaller community-based university. The radical move online has not come to pass. There are certainly models of successful universities whose presence is primarily online, in Canada and internationally. They were in that space before COVID though, and the rest of the system has largely relaxed back to primarily in-person delivery. Too often the reaction has been to look at COVID as something to never be repeated, rather than to look at it for examples where true innovation happened and should be nurtured further. Some students, also, have been traumatized by the experience of ad hoc online learning and many don’t want to go back there again. Other students, however, thrived and wish there were more opportunities for the flexibility and innovative learning that the online environment supports. To be fair, there is a relatively small group of faculty who want to teach online still for various reasons (not all related to pedagogy) – and the challenge now is how to ensure credible quality as the online teaching during COVID was done in an emergency situation but was not purposefully developed for the online world – going forward, that can’t continue.

Even as provincial government funding continues to decline relative to tuition, the demands of governments for accountability are ever increasing, and are sometimes fickle and change with Ministers and governments. This creates an enormous administrative burden for universities to provide more and more reporting and regulatory compliance in return for a relatively smaller contribution to their operating budgets, and a need for professional government relations support to ensure that university priorities and purpose are front of mind for as many key players in government as possible. This too is an international challenge. For example, the U.S. has seen a dramatic increase in regulatory requirements with legal and regulatory consequences, impacting both finances and actions on campus (Guard & Jacobsen, 2024). The challenge is that in modern society, accountability is reasonable to expect, but universities need certainty and for governments to take a longer view of the question of the value of a university to their citizens.

The increasing need for, and expectations of, student services have also created pressures on university finances. By themselves, increasing and more diverse communities of international students on campus creates the need for services unique to that student population. Given the fees the students pay, universities must be responding to those needs. There are many other enhanced services required addressing needs of the whole student community: enhancing accessibility; mental health support; sexual violence supports; supports for Indigenous students and the response to the Truth and Reconciliation Commission report; and supports for underrepresented and vulnerable student communities to name a few important examples – and there are many others. Few, if any, targeted funds have been directed to universities to fund these supports, which means that universities must find ways to redirect funds that were previously allocated for other purposes. Highlighting the cost associated with these important initiatives, both external (government) relations and student services wages have been shown recently to have indeed been the greatest factor in the growth of administrative expenses at universities in Canada (Usher, 2024). There, increases are seen to be well over 100% – 167% in the case of external relations, and 133% in the case of student services.[1]

There is no simple path forward – in many ways this is a very wicked problem where improvements are possible but absolute solutions are not. No matter what specific path a given university takes, there needs to be much greater understanding and collaboration between the (somewhat artificially) distinct academic and administrative arms of the university in order to navigate these times. Academics must recognize the impact of enrolment on revenue and institutional sustainability and have a reasonable level awareness of the broader challenges of administration posed by government actions. Responsibility lies with both faculty and administrators to both seek out and provide this awareness. Ideally, objective conversations would happen at department/faculty/school levels about the true value and viability of programs, and where cross-subsidization is warranted to support smaller or more expensive programs critical to their core mission – while maintaining overall financial sustainability. There needs to be more engagement of administrative offices with academic bodies to better understand the administrative role in, and impact on, the delivery of the academic mission. Administrative offices will often make changes to processes and policies without context, and without consultation – which can often create unnecessary stress and work, where the same goals could have been achieved in different ways by speaking to those impacted. Universities where these silos can be broken/breached have a better chance of navigating the uncertain waters we face right now and might even find ways to thrive in these times. Universities that tolerate tension and even confrontation between academics and administrators will not be so lucky and may face major challenges that require drastic actions that are not necessarily guided by their core academic mission.

As part of this engagement between administrative and academic areas, more transparent budget modelling and processes are required. Hanover Research summarizes the strength and weaknesses of a number of budget models at use in colleges and universities (Hanover Research, 2023). This deeper engagement is possible, in principle, with budget models like Activity-Based Budgeting or Responsibility-Centred Management, but for it to work the administration of the model needs to be collaborative. Academic units need to be able to see and understand the actual cost drivers of their operations relative to revenues, and be given the chance to respond, and be accountable for managing those costs – and to adapt where opportunities exist to reduce those costs. They also need to be able to see the real value and benefit to them of a thriving and diverse student body not just in the academic life, but in the financial health of their programs. Administrative offices need to be truly accountable that the services they provide are optimized to support the core academic mission and ensure effective and efficient service standards back to the rest of the university community. Overheads, and operating funds cannot simply be “imposed” but rather there must be mechanisms where they are discussed and justified and – as much as possible – agreed to by the revenue-generating academic units. That removes the sense of sole ownership and responsibility of the distinct functions that gets in the way of collaboration and helps to ensure they are working wisely and coherently. These sorts of budget models have been implemented at many universities, but rarely in the fulsome way that allows for true collaborative action to ensure the overall success of the university.

The coming years will be interesting, and worrying, to watch.

References

British Council. (2015). China records major growth in higher education and calls for the development of strong university-industry links. https://opportunities-insight.britishcouncil.org/news/market-news/china-records-major-growth-higher-education-and-calls-development-of-strong

Clarke, H. C. (2003). Growth and governance at Canadian Universities – An insider’s view. UBC Press.

Guard, L. H., & Jacobsen, J. P. (2024, May 9). The lawyerization of higher education. The Chronicle of Higher Education. https://www.chronicle.com/article/the-lawyerization-of-higher-education

Hanover Research. (2023, October 23). 6 alternative budget models for colleges and universities. https://www.hanoverresearch.com/insights-blog/6-alternative-budget-models-for-colleges-and-universities/?org=higher-education

Jack, P. (2023, September 27). World university rankings 2024: China creeps closer to top 10. Times Higher Education. https://www.timeshighereducation.com/world-university-rankings/world-university-rankings-2024-china-creeps-closer-top-10

Kozelj, J. (2023, August 16). Inside the shutdown of Quest University. University Affairs. https://universityaffairs.ca/news/news-article/inside-the-shutdown-of-quest-university/

Nietzel, M. T., & Ambrose, C. M. (2024). Colleges on the brink. Inside Higher Ed. https://www.insidehighered.com/opinion/views/2024/02/05/most-colleges-finances-are-biggest-challenge-opinion

PwC. (2024). Financial sustainability of UK universities: PwC findings. Universities UK. https://www.universitiesuk.ac.uk/what-we-do/policy-and-research/publications/financial-sustainability-uk-universities

Ross, J. (2024, May 6). Australian universities saved by windfalls but future looks bleak. Times Higher Education. https://www.timeshighereducation.com/news/australian-universities-saved-windfalls-future-looks-bleak

Statistics Canada. (2023a). Table 37-10-0018-01 Postsecondary enrolments, by registration status, institution type, status of student in Canada and gender [Data table]. https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/t1/tbl1/en/tv.action?pid=3710001801

Statistics Canada. (2023b). Table 37-10-0026-01 Revenue of universities by type of revenues and funds (in current Canadian dollars) (x 1,000) [Data table]. https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/t1/tbl1/en/tv.action?pid=3710002601

Statistics Canada. (2023c). Table 37-10-0045-01 Canadian and international tuition fees by level of study (current dollars) [Data table]. https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/t1/tbl1/en/tv.action?pid=3710004501

Usher, A. (2024). Growth and cutbacks. Higher Education Strategy Associates. https://higheredstrategy.com/growth-and-cutbacks/

How to Cite

Butler, M. (2024). Financing Canadian colleges and universities in the 21st century. In M. E. Norris and S. M. Smith (Eds.), Leading the Way: Envisioning the Future of Higher Education. Kingston, ON: Queen’s University, eCampus Ontario. Licensed under CC BY 4.0. Retrieved from https://ecampusontario.pressbooks.pub/futureofhighereducation/chapter/financing-canadian-colleges-and-universities/

- Alex Usher’s “One Thought to Start Your Day” blog is especially useful and interesting to follow for anyone interested in university finances, and broader operations. The focus is Canada, but global issues and comparators are frequently brought forward. https://higheredstrategy.com/blog/ ↵